|

Monthly archives: November 2008

Marc Hill

2008-11-26 06:15

I. Marc Hill, according to a particularly entertaining entry on BR Bullpen, was a two-sport high school superstar in Missouri. This is no surprise to me; save for one or two oddball late bloomers, every player I've droned on about on on this site must have been a god in his hometown long before he was ever a Cardboard God. I vividly remember the most celebrated high school athlete in the little town in Vermont where I grew up, Ron Schubach, our all-state basketball star, a quick, smooth guard with a Chachi haircut and an unstoppable pull-up jump shot. I still think of him as the best basketball player I’ve ever seen. I know that objectively this can’t be true, but to me he possessed the most magic. It must have been the same for all of these players enshrined in these cards. Odd as it may seem while gazing at this photo of a mouth-breather with an uncomplicated frat-boy glint in his eye, Marc Hill must have had that Schubachian mythic glow before he ever became a benchwarming journeyman known as "Booter." II. III. IV. Jerry Royster

2008-11-25 06:06

The baseball hovering above Jerry Royster’s left shoulder shows the limitations of language. Defining Jerry Royster’s role on a team with a single position, 3B, is like saying that Ben Franklin was a guy who did some newspaper work. It’s true Ben Franklin did some newspaper work, but he did a few other things too. The comparison between Jerry Royster and Ben Franklin breaks down, of course, when you weigh the relative the importance of the many roles they played. Ben Franklin: discovered electricity, invented bifocals, formed the first public lending library, laid the groundwork for a nation, etc. Jerry Royster: subbed for Rod Gilbreath on occasion, laid down the occasional sacrifice bunt, led the 101-loss 1977 Atlanta Braves in steals, etc. Even so, there is something entirely admirable in being able to do a lot of things competently. I’ve always been fond of Jerry Royster, as a matter of fact (and of Ben Franklin, too), and perhaps it has something to do with my long-held suspicion that I am useless. I remember, many years ago, in boarding school, playing catch with a friend out by my dorm's "butt porch" (a cigarette-smoking area for the adolescent denizens of the school; it was a different time). It was late in my time there, the end of senior year approaching. That spring we got stoned a lot in our room and then threw on a record, most often the Dead Set side with "Franklin’s Tower," put the speakers in the window, and hung out on the butt porch. This particular day instead of just sitting there zoning out we’d decided to play some catch. We started talking about what kind of baseball player we’d be if we could be any baseball player. I started describing my choice, a player very much like Jerry Royster. A guy you’d barely notice most of the time and then every once in a while you’d stop and say, hey, that guy’s actually fairly useful, in a quiet, unassuming way. This amused my friend greatly. "If you’re going to be a make-believe player, why would you want that?" he said, incredulous. "If we’re playing make-believe, make me the catcher who hits 80 home runs with 200 RBIs!" I refused to alter my stance. I wanted to be a utility guy who hit around .260 and could steal you a base. It couldn’t have been too much longer after this ridiculous conversation that I was expelled from boarding school. I’ve described this whole saga elsewhere, but my "judicial" occurs to me again when thinking of Jerry Royster. The judicial was a hearing where I was supposedly allowed to plead my case for staying in school to a table of students and faculty. If I’d been involved in a lot of different extra-curricular activities or charity work or sports or had had any academic prowess in one or more subjects, or had played a musical instrument, or knew how to use a computer or type or develop photographs or paint a picture or make a ceramic pot or drive or sing or identify any aspect of the natural or physical world beyond that which happened to intersect with the campus frisbee golf course I played incessantly while high, that would have been the time to mention my utility. I said very little. What was there to say? What I could have done, and probably should have done, was to show off one of my useless skills: the ability to fill out an imaginary baseball roster with some sort of an idiosyncratic theme determining inclusion. An apt team for that situation would have been a team filled with my polar opposites, the Jerry Royster-inspired all-time versatile guy team: C (and 1B and RF and LF and 3B): Johnny Wockenfuss Dave Kingman, 1976

2008-11-20 10:45

In some brief haphazard study done last night (a significant portion of it—my squinting, face-inches-from-the-page perusal of the tiny listings of the heights of players in the 1973-2006 section of my baseball encyclopedia—mocked by my wife), I have been able to formulate a hypothesis that young skilled baseball players who are unusually tall are generally valued higher than young skilled baseball players who are unusually short. The unusually tall (6'6") guy pictured here, for example, was taken by the Giants (naturally) with the first pick of the 1970 amateur draft. Other tall guys of the Cardboard Gods era, such as J.R. Richard, Rick Sutcliffe, and Dave Winfield, were also first-rounders. By contrast, Freddie Patek was not selected until the 22nd round. (It’s interesting to note that this apparent bias toward tall guys was occurring during an era in which the most dominant player was 5’7”.) I suppose it’s hard not to be impressed, as scouts must be, when a guy towering over the other guys on the high school or college diamond displays the coordination and skills of a top-flight regular-sized guy. Tall guys stick out. Moreover, the life of anyone who grew up playing sports is sure to be haunted by painful, disheartening memories of moments when a look across the court or the field or the diamond revealed that the opposition was comprised of kids who were a lot bigger than the viewer or anyone on the viewer’s team. (Take it from an expert in this regard: those were the games that were lost before they even began.) A scout would on some subconscious level probably want to help assemble a team that would never have to make that demoralizing pregame assessment. A team of towering Goliaths! Unbeatable! The fact is, however, unusually tall guys are as rare in baseball as unusually short guys. Check out this chart on Baseball Almanac, which provides support for the notion that tall guys excelling at the major league level are beating the odds every bit as much as short guys. They should be inspirational figures. They aren’t. The best they can hope for in terms of appreciation by fans is a kind of subtly dehumanizing awe, such as the reaction the 6’8” Richard began to elicit in the dominant latter stages of his stroke-shortened career. Even the best of all the tall guys of those years, Dave Winfield, would come to be defined and demeaned, at least partially, by withering comparisons to two fellow Yankees, Reggie Jackson and Don Mattingly. At the base of the comparisons was a belief that despite his prodigious athletic gifts, which surely included the notion that on top of his speed and cannon arm and power he was simply bigger than everyone else, Winfield just didn’t have the guts or the desire of a Mr. October or a Donnie Baseball. Winfield had the final word on the matter, of course, winning a World Series (with a clutch hit, no less) and gaining entry into the Hall of Fame. Most tall guys aren’t as fortunate. If they are a pitcher and they strike a guy out, or if they are a hitter and swat a home run, they are merely harnessing their prodigious talent, no more. If they fail to do these things, they make a nice, big target for boos. I imagine Dave Kingman heard his share of boos as he drifted from team to team throughout his career as a major league tall guy. In some ways he makes a perfect mirror image of Freddie Patek. While Patek is associated with one major league franchise for whom he provided all-around skill and team play and guts and fire, Kingman is known as a disliked ill-tempered one-dimensional journeyman, loyal to no one and with no one loyal to him. In many ways the defining seasons of Patek and Kingman occurred in the same year, 1977. The consistent Patek had a typically decent season for the team he will always be associated with, the Kansas City Royals: 53 steals, solid defense-anchoring glovework at shortstop, and an at least slightly pesky .320 on-base percentage. Kingman, for his part, struck out a lot and crushed a home run every few games, managing to blast 26 dingers in all, a somewhat down year for him, while playing for four different teams throughout the course of the year. (He would be shipped to a fifth team before the following year began.) The year ended for Patek with the shortstop weeping in the dugout because his team had lost. The team the Royals lost to went on the win the World Series. Presumably, a World Series ring, something Patek would never win, was given to Kingman, a late-season acquisition who didn’t appear in any postseason games for the team. Figures. Tall guys are always getting the world handed to them on the platter. Aren't they? ****** Even the All-Time Tall Guy All-Star Team underscores the fact that the deck is stacked against tall guys. Turns out there are more unusually short guys in the Hall of Fame than unusually tall guys. (And the only guy who would really turn heads with his height if he came into a room, the team's pitcher, is not even in the Hall of Fame yet.) If the all-time short guy team played the tall guy team, I might bet on the short guys. But I'd root for the tall guys. C: Ernie Lombardi, 6’3” Freddie Patek

2008-11-19 06:14

In 1971, Bobby Murcer hit .331 with a .427 on-base percentage. He was the most effective offensive performer in the league, evidenced by the statistical measure that best adjusts for league and park conditions, OPS+; Murcer posted a league-high 181 in that category. He also manned one of the game’s most important defensive positions, centerfield, and presumably did so at a level close to that which would earn him a Gold Glove the following season. Despite all these accomplishments, Murcer finished seventh in the MVP voting. The player directly in front of him in sixth place in the voting, Freddie Patek, hit .267 with a .323 on-base percentage and six home runs. Patek did play one of the only positions on the field arguably more important than centerfield, but he didn’t win a Gold Glove at that position in 1971 or in any other year. So how did voters determine that he was more valuable to his team than Bobby Murcer? Well, I wasn’t old enough to be paying attention in 1971, but I do know that when I did get old enough to know who Freddie Patek was, I associated him with one thing, his size. More specifically, as a baseball fan I absorbed and reflected the prevailing attitude of faintly patronizing awe and admiration toward Freddie Patek. Little Freddie Patek! Not even tall enough to ride the carnival rides! But still out there bravely turning double plays with the likes of Don Baylor and Reggie Jackson hurling their hulking frames at the second base bag! I’m travelling a well-beaten path blazed by Bill James here, but the key to understanding such things as the 1971 MVP voting that ranked Freddie Patek higher than Bobby Murcer is that baseball has levels of varying visibility, and just about everything Freddie Patek did well or even competently was abundantly visible and cause for celebration by the fans. He was a good bunter. He was a good base-stealer. He was a good fielder. All three of these things can be noticed from the cheap seats and cheered for. In a sense, the fans are cheering not only for the player who executed the play but in at least some small way cheering for themselves as knowledgeable, observant baseball fans; this element is at its height in the moment after a guy grounds out to second to move a runner to third. (A walk, on the other hand, can only be clapped for politely, at best, even though it is in almost all situations more valuable than a bunt and in most situations more valuable than a steal.) And if the guy performing well on the visible level (which also includes the even more dubious or at least impossible to measure value of, for example "being fiery" or "being a good teammate") is 5’4" tall (as Freddie Patek is listed as being on the back of this 1978 card), then the applause will have an added spark to it. Call it happiness. I mean, let's face it, it’s just fun to watch a little guy mix it up out there with the hulking behemoths. I know I certainly always liked Freddie Patek. And now, similarly, I find myself drawn to Dustin Pedroia. (In fact, earlier this year I talked about him so much that my wife accused me of being in love with him.) I was thrilled when I heard yesterday that Pedroia had been awarded the A.L. MVP. As a Red Sox fan, I followed the team closely this year, and he certainly seemed to contribute a daily spark that the often injury- and controversy-beleaguered team would have been lost and joyless without. Beyond his excellence in the "visible" realm as a fiery double-smashing, base-stealing, dirty-uniformed little guy, he also had inarguably good offensive numbers, and impressed enough observers with his fielding to win a Gold Glove at a very important position. But was he more valuable than his teammate Kevin Youkilis? It’s an interesting question, and one Tony Massoratti does a great job of exploring in today’s Boston Globe. But I ain’t complaining. Pedroia’s a deserving winner, and I’m just glad a Red Sox player got the trophy. I would have been just as happy, if not moreso, if Youkilis had become the first Jewish A.L. MVP since Al Rosen. But today should be about congratulating the winner, so I think I’ll just wrap things up with something of a tribute to Pedroia (and Freddie Patek): my hastily thrown-together all-time small guy team, featuring a Hall of Famer at every position... C: Yogi Berra, 5’7½" (Love versus Hate update: Freddie Patek's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Balor Moore

2008-11-17 07:00

"People ask me if I would go back to the game if I was offered a position, and I don’t think that I would, because I wouldn’t want the insecurity." – Balor Moore, "No Moore regrets for first Montreal pick" I. You could argue, as I have tried to argue to myself, that the third baseman’s hopeless slackness is due to this not being a photo of an official pitch at all but simply a picture snapped of Balor Moore as he is tossing the ball to the umpire in exchange for a new ball. I believe this argument fails on the grounds of two bits of evidence: the bulging muscles in Moore’s right forearm and the intense, albeit somewhat battered, look of concentration on Moore’s face. These elements suggest that despite the overall impression that no power whatsoever is being generated by Balor Moore, that the pitch by Balor Moore will loop toward the plate as big and soft as a multicolored beach ball, that Balor Moore may in the next second have to duck to save his own life, Balor Moore is trying as hard as he possibly can. II. III. IV. V.

You’ll notice that the second of the two nice things the Topps writer could think to say about Balor Moore overlaps the first nice thing. In fact, Balor Moore only pitched twice against the 73-89 Twins in 1978, and he lost the game not mentioned in the first point. The undertone of desperation becomes even more apparent in the text when the reader notices that the year mentioned in both bullet points is the year before the most recent season on the card, implying that nothing at all positive, not even one good game against a mediocre team, occurred in 1979. VI. Bill North

2008-11-14 07:51

I. It must have seemed like it was going to be a blooping basehit, beyond the reach of infielder and outfielder alike. Dick Allen, in the midst of the last of his many MVP-caliber seasons, had been running from second base on the play, and from what I’ve read Dick Allen was not just a one-dimensional mangler of pitches but an intelligent player who knew the whole game well. He must have sized up the fluttering wounded quail off the bat of White Sox teammate Brian Downing and been convinced that it would touch down safely in the outfield grass. He must have set his mind on roaring across home plate with the tying run. Is there anything more exciting than speed? As the ball arced down toward the outfield grass, Oakland A’s centerfielder Billy North suddenly appeared like a flash of heat lightning. This is how I imagine it happened. One moment no one is there and an eyeblink later Billy North is a green and yellow bolt catching the ball off his white shoetops. His momentum carries him forward, toward the second base bag, and I imagine that he thought about making the throw to the infielder waiting there to double off Dick Allen. Maybe North even cocked his arm to throw. But then North must have seen that Dick Allen had no chance to beat the centerfielder to the bag. (A sign of Allen’s lack of fleetness came later in the game, when he was pinch run for by Tony Muser, who stole all of 14 bases in his nine-year career.) Billy North hung onto the ball and kept running. With speed like that, speed so transcendent it must have felt exactly like joy, why stop? The outfielder transformed himself into an infielder and stomped on the bag, ending the inning and preserving the lead with what has to be one of the more unusual unassisted double plays ever recorded. Must have felt pretty good to be Billy North that day. II. In short, they tried to steal everything they could possibly steal. They tried to steal early in games, in the middle of games, and late in games. They had bid adieu the previous year to the two-year experiment of using sprinter Herb Washington as a Designated Pinch Runner, but in his wake they now employed two Herbly reserves, Larry Lintz and Matt Alexander, who played in a combined 129 games and had only 31 at bats between them (Alexander had 30 of them and produced the duo’s lone hit); the two pinch runners combined to steal 51 bases. Their personal stolen base totals (Lintz: 31; Alexander: 20) were topped by several teammates, including Phil Garner with 35, Claudell Washington with 37, Don Baylor (!) with 52, Bert Campaneris with 54, and team leader Billy North with 75. In all, the team, which even featured Sal Bando swiping 20 bags (more than his stolen base totals in his previous five seasons combined), stole 341 bases, the most by any post-deadball-era team. The question is, did it work? Did it allow the A’s to stave off their eventual crushing demise? Well, they didn’t win their division for the first time in six seasons, but they certainly did a lot better than they would the next season, when the bottom really dropped out. But did all the stealing lead to more wins? My thinking is that maybe it did (but maybe it didn't). First of all, the A’s had what I think is a decent success rate on steals that year, given the fact that to steal all those bases they must have had the green light all the time, even against pitchers and catchers who were very difficult to steal against, and given the fact that they certainly weren’t ever going to take someone by surprise with their running game. For the season, they stole bases at a 73.5% clip. I believe experts in the analysis of baseball stats have come to the conclusion that a 75% stolen base success rate or better will help a team’s offense, while anything less will hinder it. But since the A’s were only slightly below that mark, I figure they could get a pass in this regard. More tellingly, the A’s scored quite a few more runs that year than they would have been expected to, given their on-base and slugging percentages. I did a couple of calculations using the Runs Created formulas, and it seems they should have been expected to score 620 or 621 runs. They scored 686. It stands to reason that all the stolen bases helped them get those extra 65 or 66 runs. How much were those extra runs worth? If they had scored only 621 runs, they would have been expected, using Bill James' Pythagorean Expectation, to win 83 or 84 games. They won 87. However, if you feed their actual runs scored and runs allowed into the Pythagorean Expectation, it turns out they should have won 91 games, which would have put them a game ahead of the division-winning Kansas City Royals. I don’t know why they performed below their expected win total, but is it possible that they lost a handful of close games in late innings because at the end of those games they had exhausted themselves with all the running? III. It didn’t. The Giants returned to their familiar Padre-haunted irrelevancy near the bottom of the National League West standings. It wasn’t Billy North’s fault, however. After a subpar 1978 season he bounced back with his customary good leadoff man numbers, posting a .386 on-base percentage, a team-high 87 runs, and more stolen bases, 54, than any San Francisco Giant has ever had. In fact, this last element of his 1979 season made him the single-season record-holder for the teams on both sides of the bay (other players had stolen more in a season when the franchises were located in other cities). Though this record still stands for the San Francisco Giants, North was soon wiped off the top of the Oakland A’s record book by Rickey Henderson. Perhaps this began the slow erosion of Billy North in the collective memory of baseball fans. When one now thinks of stolen bases and the Oakland A’s, there’s not much room for anyone but Rickey. IV. Lucky for us all, when the ball started diving toward its seemingly predestined landing spot in the grass, Billy North appeared.

Bonus trivia question: Seven players stole more bases than Billy North in the 1970s. Can you best-of-seven the question by naming four of those seven? No Feldmaning; i.e., no peeking at Internet or other sources for the answer (the term, which should be in wider circulation, is based on Feldman, a minor character in a Daniel Clowes comic). Ted Simmons

2008-11-12 06:15

I. Last week on the bus a guy in a Cubs hat sitting near me eyeballed my Red Sox hat and we started talking baseball. It’s a pretty long ride, and after a while we ran out of things to say. I waited a few minutes to turn to the book I’d had on my lap, and not long after that the bus emptied enough for him to move a couple seats away and spread out and stare out a window. He was big guy with a mustache. He wore a windbreaker of a championship 16" softball team (the kind of softball I’d never seen until I moved to Chicago). I’d thought he was a little older than me, but he was probably the same age. From our conversation I’d learned that he’d grown up loving baseball players from the 1970s. II. III. IV. V. I nodded. This was early in my conversation on the bus with the Cubs fan with the flask of liquor in his pocket. From there we started talking about the Hall of Fame. The All Time Greats. I said Ron Santo deserved to be in the Hall of Fame. "December 10," he said. (I think that’s the date he mentioned.) "That’s when they vote?" I asked. ("They" are a committee of Hall of Fame inductees who may or may not finally agree to let Ron Santo join their ranks.) He nodded. We bitched about Joe Morgan for a little while, singling him out for blame in keeping Santo on the outside looking in, then the guy started telling me about the posters in his room. I’ve ridden a lot of buses, but no one has ever told me about the posters in their room. "I’ve got three. Robin Yount. Pete Rose. Thurman Munson. They played the game the way it was supposed to be played." VI. Jeff Terpko

2008-11-10 07:02

I have no memory of anyone named Jeff Terpko. You'd think a baseball player from the 1970s who never registered in the mind of someone obsessed with 1970s baseball might be somewhat inconsequential, but it turns out this is not the case. In fact, if I had to boil down to one sentence this endeavor of looking for inspiration and amusement in my shoebox of childhood cards, I might say "No one is inconsequential." Everyone has a story. Jeff Terpko, for example, had been around for quite a while at the time of this 1977 card, many years and small cities listed in his complete major and minor league pitching record. Right in the middle of Jeff Terpko’s long meandering story, after the listings of his stops in Geneva, Buffalo, Pittsfield, Burlington, Greenville, and Burlington again, is a line at Spokane that has no numbers but just the words "DID NOT PLAY." I’ve seen this before and have never understood what it means, exactly, and have only wondered what life must have been like for those going through years like that. Terpko was 23 in that year, six years into a pro baseball career and without a taste of the majors, six years of making just enough to eat gas station sandwiches during spine-numbing bus rides. But on he went the next year, going in one year from Pittsfield to Spokane to, as the front of the uniform shown here would have it spelled, TexaS. He spent the year after that entirely in Spokane, but then in 1976 seemed to stake his claim on a major league career by pitching solely for the Rangers, appearing in 32 games and posting an admirable 2.38 ERA. That promising number is at the lower right of the back of the card. At the upper left of the card is an enigmatic line that could be interpreted as the opposite of unequivocal promise: "Acq: Traded Player, Ret’d by Phillies. 4-10-71" Here’s the full transaction, courtesy of Jeff Terpko's page on baseball-reference.com: November 3, 1970: [Jeff Terpko was] traded by the Washington Senators with Greg Goossen and Gene Martin to the Philadelphia Phillies for a player to be named later and Curt Flood. The Philadelphia Phillies sent Jeff Terpko (April 10, 1971) to the Washington Senators to complete the trade. So finally, through the seemingly inconsequential and absurd figure of a player to be named later turning out to be a player already named, we reach the realm of history, or at least what could be considered a footnote to history. I am referring to that most notable player involved in the Terpko for Terpko trade: Curt Flood. Before being involved in the trade that featured two teams treating Jeff Terpko like a bad luck charm, Curt Flood was involved in arguably the most important transaction in baseball history, a trade between the Cardinals and the Phillies that Curt Flood refused to accept. His refusal to report to the Phillies set in motion the end of the reserve clause in major league baseball, a clause that had allowed teams to treat players like chattel (or like Jeff Terpko) for decades. Flood’s good major league career was basically brought to an end by his taking a stand, but the trade listed above did allow him to have a few final largely ineffective at-bats with the Senators in 1971, a season that proved to be a footnote to what eventually came to be seen, because of his brave and self-sacrificing stand, as a historic career. A footnote to that footnote to that footnote shows that Terpko had a knack for ghosting peripherally at the edges of careers of guys taking stands. Later he was traded for Rodney Scott, who in turn, some years later, was released by the Montreal Expos, which caused Expos teammate Bill Lee to stage a one-man strike against the team. If I remember correctly, Lee first bolted from the stadium before a game to drink beer and play pool for a few innings, though I think he did return when he thought he might be needed in relief. I think the next day he went into the general manager’s office and sat there chanting in a lotus position until the general manager arrived and told him his services would no longer be needed. Terpko's exit from the majors happened a few years earlier and was more conventional. He entered a June 2, 1977, game in the sixth inning against the New York Mets. His team, the Expos, was down 6-3. He walked Len Randle, allowed Len Randle to steal second, got Felix Milan to fly out, then walked the bases full and was yanked from the game and never called on again. Cardboard Books: Dirty Water

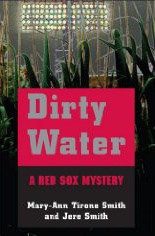

2008-11-07 06:19

The gripping new novel Dirty Water, coauthored by mystery writer Mary-Ann Tirone Smith and her son, Jere Smith, begins inside Fenway Park in the midst of the Red Sox' 2007 championship season. I was, of course, instantly hooked. But I can’t say that I was surprised. As a grateful fan of Jere Smith’s rabidly passionate and generous blog, A Red Sox Fan from Pinstripes Territory, which brings readers along for the ride (with copious photos, videos, and pointed descriptions) every one of the many times he goes to cheer his voice hoarse for the Red Sox, I would have been surprised if the book had opened anywhere but Fenway. (Smith, using the name of his blog as a commenter name, shows up in Cardboard Gods comments from time to time, most fittingly in terms of the discussion here as a keen-eyed detective of the moments depicted in baseball cards featuring action shots.) From that opening scene, in which a newborn in seemingly dire health is mysteriously abandoned in the Red Sox clubhouse, the well-plotted, plausible novel hurtles forward with the help of well-drawn characters and a deep and satisfying sense of setting. The Red Sox themselves show up periodically to contribute to both of these rich elements of the book. The appearances by the players, which if handled poorly would have doomed the book (at least for baseball fans), is handled by the authors with a pitch-perfect ear for how, for example, Jason Varitek would act when confronted with an ill infant in his clubhouse, or what Big Papi would do if a player in the Sox’ minor league system came to him for help in a very difficult situation. The book also features an innovative way of propelling the action forward by periodically inserting entries and accompanying reader comments from a fictional Red Sox fan’s blog. The blogger in the novel comments on the ongoing mystery that began in the Red Sox clubhouse and offers as-yet unrevealed details, which at times gives the blog entries an ominous feel as the reader can’t help but wonder how he knows so much about the case. Additionally, the reader comments serve brilliantly as a kind of Greek chorus lamenting and celebrating the downs and ups of the mystery (and the Red Sox’ season). At the core of the lived-in, baseball-saturated world of the novel is the police detective working to solve the case, which comes to involve not only the abandonment of a baby but kidnapping, murder, and international human trafficking. This detective, Rocky Patel, is an excellent character, unusual and compelling, and unshakably dogged in his pursuit of the truth below all the fascinating and grisly murk of the mystery. Because of his magnetic presence, I would have been drawn forward by the book even if it hadn’t so richly and authoritatively portrayed a world in which the Red Sox are as intrinsic to life as water or air. Lucky for me, and for all fans of baseball and of fiction with deep roots in the world it describes, Dirty Water gleams in the glow of the brilliant light stanchions of Fenway.

Permalink |

No comments.

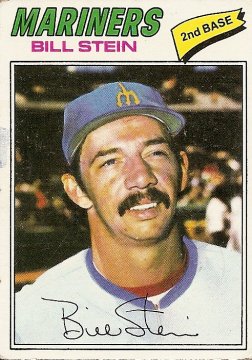

Bill Stein

2008-11-05 06:07

Contrary to my propensity for angry nihilistic self-hating screeds, I’m not an altogether hopeless guy. For example, today’s a good day, a hopeful day. I feel like I might have a leader. Last night, after the first speech of the new president-elect of the United States, I pointed at the TV and declared to my wife, "I want to run through a fucking wall for that man." I really meant it, and felt an emotional tremble in my voice as I said it, but in truth as a declaration of intentions it was nice and blustery and vague. I didn’t actually have to commit to anything. I mean, I could have said, "Where’s the nearest Peace Corps induction center?" or "Get me the number to an organization that sends guys into locked wards to teach the criminally insane to square dance." Since I’m kind of a quitter, and don’t enjoy quitting, I try to avoid commiting to anything. But here it is the day after and I still feel hopeful and like I want to be part of the Yes We Can battalion instead of continuing on with my usual lonely mantra of No I Can’t. What does this have to do with Bill Stein? Well, not much. But first of all, at the risk of starting the first day of a hopeful new warmly inclusive era on a sour and mean-spirited note: whoo, he ugly. I only say this because I love my baseball cards, every single one of them, but most especially the ones featuring the luckless marginals, the nobodies, the drifters, the inglorious, the big-eared and mush-nosed and chinless and soggily-mustachioed and dim-eyed. The ugly. Hallelujah for the ugly! Today we spread wide our embrace to include every-fucking-body, the excluding myth of the Aryan suburban blond Mr. Joe America fatally punctured, hallelujah. And second of all, I mean the second reason I am talking about Bill Stein on this hopeful Yes We Can day, is that before this day was This Day it was, in the ever-evolving myth of the Cardboard Gods, Expansion Day. On this day, November 5, back in 1976 (the year in which the country eructed stars and stripes from every pore in celebration of that first expansion into nationhood 200 years earlier), the heaven that has presided over my life expanded. That was the day of the expansion draft that breathed life into two new major league teams, the Toronto Blue Jays and the Seattle Mariners, and breathed life into the flagging careers of dozens of men on the professional baseball scrap-heap, and breathed life into the hopes of everyone who has ever felt the world closing in all around them. Life contracts, gets smaller, narrower, more and more hopeless. But life also expands. So today on Cardboard Gods we celebrate that expansion, as we will every November 5 from here until the molecules currently comprising my singular body expand to mingle with the body of all. Happy Expansion Day, everybody! * * * And speaking of expansion, Bronx Banter’s ongoing Lasting Yankee Stadium Memory series recently expanded to include my obscenity-laden ramblings about car wrecks, criminal mischief, and Steve Balboni. Cesar Cedeno

2008-11-04 06:01

I have to go early to my job today and stay late. I couldn’t sleep last night, worrying about all the things I have to get done. Eventually that worry expanded into a metaphysical reckoning, something that should never be entered into at two in the morning. I got out of bed and went to the room with the computer and sat there on the edge of the futon in my underwear holding my stomach. The small blue circle of light around the on-button of the computer monitor flashed. I got more and more upset. Felt trapped. I did some push-ups. I punched myself a few times in the head, even though I swore I’d never do that again. I pondered existence, panicking. The Big Question: What is this shit? I took deep breaths. I fucking prayed. I pray sometimes. In fact that’s what I’m doing now, what I’ve been doing all my life with the Cardboard Gods. I was able to go back to sleep for a couple hours. Now I’m up and have to go do my job, which has gradually become the job of three people. Everyone in the cubicles around me is doing the job of three people, too. This has something to do with the increasing number of empty cubicles. At night we watch the news of the economy collapsing, jobs disappearing. I’ll never be a father. I wish I was mildly brain-damaged, free of responsibility and expectation. Only an asshole would say such a thing. My stomach hurts now, and my back, and my eyes have that gauzy feel from lack of sleep. My shoulders are tight. None of the things I will do today will be memorable. If I get old and look back at my life this day will not be there, even though it’s a potentially historic day. Where were you the day Obama was elected? Where were you the day Obama was shockingly defeated? What did you do? This is what my grandchild would ask, presumably, if I were to live a life that included children and grandchildren. Anyway I’d have no answer. I worked. I went to my job and did the shit you do to stay clothed and fed. The future curdles. This is a thing only an asshole would say on a day that many are feeling hopeful about. Change, great. I voted for "change" and did so happily. (I voted early, in some kind of old municipal hall that was also hosting a Halloween dance. No one was at the dance yet. "Jungle Boogie" by Kool and the Gang was playing. There was a skeleton and skulls and a Darth Vader head hanging over the door to the building.) Will it impact my life? I doubt it. The future used to be one thing, and now it’s something else. It’s clearer, less vague, narrower. I’m 40. I will work until my heart ceases, most days squares to put a line through when completed. Cesar Cedeno, shown here around the time it had become clear that he was after all never going to be the next Willie Mays, seems to be both safe and irrelevant. The play is happening somewhere else. He has lost his helmet. He has been moved from centerfield to first base. He has aged. He is looking toward the play going on without him. In a few years he'll be altogether gone from the scene. |