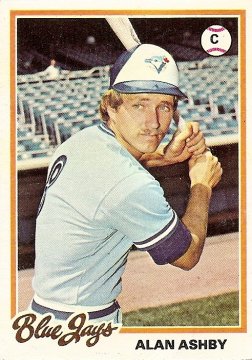

Alan Ashby

December 17, 2008

I was born into losing. This may seem like a particularly glum and self-pitying thing to say, but facts are facts: I was the younger sibling of an athletically able boy who would always be older, bigger, and stronger than me. This may not have had such an impact on my sporting won-loss record had my family remained throughout my childhood in kid-glutted suburban New Jersey, where I was born, but just as I was getting old enough to be able to perform sports-related tasks, such as throwing and catching a ball, my family moved to rural Vermont, where the great majority of the time the only game in town was the one that pitted me against an older, bigger, stronger boy.

***

During the Cardboard Gods era, i.e., the heavy card-collecting years of my childhood, i.e., 1975–1980, the 100-loss plateau was surpassed nine times. The Tigers, Expos, Braves, and A’s all had a season during that span in which they suffered over 100 losses; the Seattle Mariners had two such seasons; and the team of the player featured here, the Toronto Blue Jays, lost over 100 games not once, not twice, but thrice. And they weren’t even in existence for the first two years of the era.

***

Perhaps because I was born into losing, I spent a lot of time fostering fantasies of victory. I was willing and able to do this on my own, but I loved when my brother joined me, either as we rooted for the same team to win or as we bounded around our big side-yard pretending to be key members of the same winning team. Our baseball team was the Boston Red Sox, but when the weather started getting cold and the trees turned skeletal we shifted our attention to football. The only channel we got reception for that showed football was CBS, which featured the Dallas Cowboys nearly every week. They usually won. After those wins, we’d go out into the cold fading day and for a little while pretend to be Roger Staubach and Drew Pearson connecting for touchdown after touchdown.

***

A look at the Toronto Blue Jays’ 1977 roster might lead one to believe that the team’s executives decided to field a team of players that just happened to fall to them, like a collection of damaged drifters who all end up in the same run-down coastal outpost, drinking tequila shots at tables for one and nervously keeping an eye on the door. But in fact the team was built with a conscious plan and not by mere apathetic passivity. The plan may well have had a long-term element to it, especially considering that within a decade of their birth the Blue Jays would be contending for division titles, a development their fellow 1977 expansionists, the Mariners, fell far short of attaining. But whether there was a long-term element to the plan or not, the existence of trades made by the team in its early moments shows that the franchise was not merely naming players when forced to by the expansion draft but was seeking out players on other rosters and actively devising ways to bring those players onto their own roster. It seems, through this lens, that the Blue Jays decided that if they were going to have any structural integrity at all they would have to make sure to have able catchers, those players often referred to as “backbones” of teams. The first trade they ever made, for a player to be named later, was to acquire veteran catcher Phil Roof. The first trade they ever made where they actually had someone on hand to offer in return came about a week later in an Expansion Day trade of Al Fitzmorris for Doug Howard (who would never play a game for the Blue Jays) and Alan Ashby. Ashby would serve as the team’s first regular catcher, the first backbone, the first rock upon which the tower of the franchise would be built.

***

Ashby became an official member of the team just as it was starting to get cold, in November, the time of year that found my brother and me pretending to be Staubach and Pearson. My brother always eventually grew bored with that shared side-yard fantasy. He either quit to go climb deep into one of his science fiction books or decided it was time we played against one another. Our one-on-one matches went the same way in every sport we played, but they were stripped to their grimmest essence in the wake of the Staubach-to-Pearson fantasies. I’d punt the ball to my brother and he’d Robert-Newhouse through me for a touchdown, then he’d punt the ball to me and I’d have it for a few seconds before he grabbed me, ripped the ball from my hands, tossed me aside like a candy bar wrapper, and ran for another touchdown under the cold gray sky.

***

Alan Ashby went on to play for seventeen years in the major leagues, most of those seasons as the on-field shepherd of the often-dominating Houston Astros pitching staffs of the early 1980s. But he never caught more games or logged more at-bats than in that first long season with the Blue Jays. As mentioned earlier, the catcher is often thought of as the backbone of a team, but the catcher is also a team’s most intimate witness. The catcher can see all the other players on the field at all times, and unlike the three outfielders who also have a comprehensive view the catcher is involved in every play at close range. All season long Alan Ashby had the best view of the daily pummeling the team was sustaining, run after run stomping down on the plate in front of him as he held his mask in his hand, doing nothing because there was nothing to do. The photo shown in the 1978 card at the top of this page shows this witness to monumental failure looking a little guarded, a little sad. An aura of powerlessness emanates from his bunched shoulders and placid, introspective features. But there must be in this photo evidence of a tenacious will, too. A full ten years after presiding over the 107-loss season, a 35-year-old Ashby recorded career highs in home runs, RBI, batting average, and just about every other offensive category. Everyone’s born into losing. Can you bear witness to the losing and continue to show up, year after year?

***

(Love versus Hate update: Alan Ashby’s back-of-the-card “Play Ball” result has been added to the ongoing contest.)

1. I’d love to write something pithy, but all I can say is “wow, that’s good.” I’m sitting here almost in awe.

2. I started paying attention to baseball four or five years after the Blue Jays’ first year, but I only remember five of their 1977 players as being active. Three of them (Ashby, Whitt, and Cerone) were catchers.

3. 1 : Thanks very much, Ken.

2 : I feel like there were a couple other Blue Jays besides Whitt who made it to the promised land of the good mid-’80s teams. Jim Clancy, who I’m pretty sure was an Expansion Day arrival, springs to mind. Garth Iorg, too, maybe.

4. Speaking of the early Blue Jays, make sure you are in a good mood before you read Doug Ault’s life story. It’s as grim as this December weather.

5. 3 : I just checked: Clancy and Iorg did both make it to the Jays’ ’85 division-winning team, but Iorg, though taken in the expansion draft, was not an official original Jay, not making it to the majors until ’78.

My guess is that Clancy was the last Expansion Draft guy for either the Mariners or Jays to be playing in the majors (he kept it going until ’91).

6. well, Ennui, thanks for making me look up Doug Ault on Canadian Baseball News. There’s a holiday story for ya.

Winning and losing in families can be a cruel dynamic: I remember my grandfather teaching us to play chess. He would soundly beat my brother, his namesake and first grandson, repeatedly, sometimes in just a few short brutal moves, leaving the 8-year-old weeping with frustration. Until my brother finally won a game one day. My grandfather folded up the board, accepted defeat, and never played chess with him again.

The moral of this story is that yes, we need to bear witness to the losing and continue to show up, year after year.

Because eventually the older, bigger guy will get weak and decrepit and you can pound the crap out of him.

7. Alan Ashby was one of my favorites when I was a kid.

I was a catcher, so all catchers were automatically cool, but there was more to it.

I was also an Astros fan, and at that time, Ashby would catch, on three consecutive days:

J.R. Richard

Joe Niekro

Nolan Ryan

Even after Richard’s stroke, that’s still the Express and the Younger Brother (Knuckles and Shaved Fingertips?) in the same rotation… 70 games a year of THAT mess, plus whoever else the ‘Stros threw out there (Ashby was still there for Mike Scott’s big years).

The hitters haaaated it, obviously — bad enough trying to hit in the Astrodome — but CATCHING it?

Alan Ashby: quietly awesome.

8. In those days, I’d open the pack of cards an start shoving through them, and you’d see “Blue Jays” or “Mariners” and you’d feel they were useless, almost a place holder. Seeing those teams on the cards from that era (like the ’78 one Josh shows) still makes me flinch.

9. Could somebody post a link to that Doug Alt story? I just tried searching for it and couldn’t find it. I remember he had a little trophy on his first card indicating he was a Topps Rookie All Star (or whatever the exact designation was) and assumed he was Something Big on the rise and wanted to keep his name in mind so I could claim to have been there from the start as he rose to the heights of the game.

10. http://slam.canoe.ca/Slam/Baseball/MLB/Toronto/2005/04/07/986237.html

I was going to make a crack about how maybe the losing got to Ault, but then I read that story, found out what really happened, and felt depressed. I didn’t even realize that it was so close to the holidays.

11. 5 Rick Honeycutt wasn’t an expansion draft guy (the Mariners traded for him during the 1977 season) but he kept going until 1997.

12. Josh-

There is a guy named Raol Torres writing on Bill James’ site (billjamesonline.net) who reminds me of you. Unfortunately, it’s a pay site, but if you can, you might enjoy his work.

13. great piece:

my sister had a series of apparently fragile hamsters in that era, and she named one of them ashby. she wasn’t a baseball fan, so the name had nothing do with the catcher. but because of the name, i very clearly remember noticing ashby’s in the paper. my grandma was serving scrambled eggs and letting her cigarette ashe get long enough to make everybody nervous, and i was looking in the LA Times box scores and, boom!, there was an ashby. i sort of followed him, vaguely, from then on. i caught, too, and when he went to houston he seemed to kill my dodgers. it seemed like three of his annual eight homers would come against us… i’d have to look it up to see if that impression is fact-based, but that’s what i remember.

14. spudrph, I’m glad that I’m not the only one who noticed the resemblence. Roel also occasionally writes for the Hardball TImes.

15. Got a chance to work with Alan Ashby in the Texas-Louisianna League in 1995. Very nice and knowledgable baseball man. I was partial to the expansion Mariners while my brother adopted the Jays that summer of 1977. Even at 11 years of age it was interesting to see 2 teams being built right before your eyes.

16. But there must be in this photo evidence of a tenacious will, too.

Is that a hint of a smirk on his face that I see?

Eye brows slightly perked, corners of the mouth drawn in.

Is he say’in “Go ahead – bring it – you can’t touch me …”

7 by Wabi-sabi reinforces this belief in me.

Great post Josh – This is why I voted for Johnny Bench.

yeesh…the Ault story is right out of a Greek tragedy.

Sad. I remember his name, for some reason, embodying those early Blue Jays.

I was also surprised to realize that the pathetic, almost irrelevant ‘post-Seaver-trade’ Mets never quite sank to the 100 loss level. I mean, those were some dark years over at Shea.

Apparently, in the neo-biblical seven season draught following Tom Terrific’s initial deportation,(and concurrent metaphoric End of My Childhood), the Mets lost between 94 and 99 games every single year, except, of course, the strike-shortened 1981 campaign, where they dropped 62, and were on pace (percentage-wise) to lose 97.

Gee, I guess things weren’t so bad after all.