|

Monthly archives: November 2007

The Basketball Kid Takes a Stand

2007-11-30 10:11

Episode One: The Last Timeout

First panel: snow falling through the light from a streetlamp Second panel: main street in a small town at night, parked cars buried in snow, stores dark, snowy sidewalks not even dotted with footprints Third panel: a small-town baseball field covered with snow Fourth panel: snow falling down past the windows of a lit-up high school gym, the parking lot packed, the light in the windows glowing Fifth panel: people jammed shoulder-to-shoulder on wooden bleachers, some in thick sweaters, some still wearing parkas, some with mouths open in exhortation, others close-mouthed, worried, everyone looking in the same direction, everyone with an expression that one way or another says this moment matters And in this moment the clock is frozen with just a few ticks left. "OK, Kid," the coach says in the last possible timeout huddle. He is looking where everyone else is looking. All the spectators, all the other players. Everyone praying the same prayer. A buzzer sounds. The hometown players put their hands together and bark out their huddle-breaking chant: "Believe!" Four of the white-jerseyed players take the floor. Others find a seat on the bench. One player lingers at the edge of the court, standing, mopping his face with a towel. Everyone keeps their gaze on him. Is he thinking of all the close scrapes and near misses and miraculous last-second heroics? Is he wondering if his luck may have finally run out? Is he wondering if the many setbacks already experienced during this difficult game are the harbingers of a damning defeat, a beginning of a new life of losing, a new life of the constant unraveling of confidence and faith? A ref stands nearby, the game ball in his arms. "Anytime you’re ready, Kid," the ref says, a whistle clenched in his teeth. But The Basketball Kid is still thinking. He’s thinking of everything. The close scrapes, the near misses, the miraculous last-second heroics. The difficulty of the game at hand, the possibility of losing, the possibility of that loss opening up into a whole life of losing. Time out, he wants to say. He is wondering if this is the beginning of the end of The Basketball Kid, but he wants to carve out a little shelter in time and linger there and wonder just a little about the opposite of the beginning of the end. But such shelters don’t exist. He takes his towel from his face, but then instead of tossing it in a customary display of cleancut small-town politeness and warm-hearted small-town kindness to the team manager, an awkward addle-brained bespectacled dufus that The Basketball Kid long ago rescued from friendlessness, The Basketball Kid just lets it drop to the ground. It’s a small but ominous departure from the usual script of heroism, and it registers in the crowd with a nervous murmur. The only person seeming not to focus on the intimations of the towel crumpled rudely on the floor is the author of the gesture. His mind, previously so pure, so focused on The Now, has finally, perhaps irrevocably, begun to wander. Mickey Klutts

2007-11-29 04:05

Leo Cardenas

2007-11-26 16:39

After not having written for a few days, I tried to start the day by writing in my notebook. The pen seemed like a charred log in my hand. I forgot how to write. I pushed the charred log around a while, then stunned myself with lunch, then pounded some instant coffee, then paced around some, then finally left the apartment. A couple days earlier I'd left my house keys in a motel 600 miles away, so I needed to find a place that would copy my wife's set. It was a cold gray day today and I walked down Chicago Avenue, which seemed even dingier than usual, grimy yellow signs hanging over dead and dying businesses. I walked for a mile or so and finally found a hardware store on Ashland but stood for several minutes by the counter while a homely pale woman in glasses behind the counter ignored me. When she finally finished fiddling with a pricing gun she looked past me to a guy who had just come in and waved him over to continue a discussion that had apparently begun earlier. I just stood there with my stupid keys, wondering if I'd become invisible. Eventually a homely pale man in glasses appeared and made me copies of my keys, our dealings concluding with no exchange of niceties. "Pay at the register," he muttered, not looking up. By the time I got back to my apartment building, I had spent over an hour on the errand. The key to the front door of the building didn't work. I cursed and started thinking about how I could have saved myself all this trouble if I'd not left my stupid keys next to the television in the motel 600 miles away. Why didn't I put them in my bag? Why didn't I just keep them in my pocket? Why didn't I case the room like everybody knows to do before walking out the last time? I stalked down the street getting angrier and angrier, passing ancient Ukrainian women trudging along with their grocery bags. I started punching myself in the head. I did it a couple times. The first time was sort of a heel to the forehead blow, and then the next was a clenched fist to the side of my head. The heel shot sort of made me see stars. Both punches together made me feel a little dizzy. I've promised my wife I'd stop doing this, hitting myself in the head, but every once in a while when I make a stupid mistake that seems to unlock the door that keeps the infinite snarl of stupid, confusing modern living at bay I start falling into a downspiral of frustration and self-laceration that ends with the utter stupidity of me beating myself about the head. The only thing to be said for this personal tic is that once I do it a couple times I generally stop, as happened today. Woozy, I kept walking past the kerchief-headed Ukrainian octagenarians, wondering if I was going to fall over. I managed to stay on my feet. I found a dollar store run by a warm, jovial Hispanic dude who made me feel like an honored customer even though he only made $1.09 off me. On top of that, his key ended up working, allowing me back into my apartment, where I promptly proceeded to waste the rest of the day. Leo Cardenas, here you stand at the twilight of your career, when you should know better, displaying a batting stance like that of a rank beginner, a toddler with a bat, body facing the pitcher full-on. Leo Cardenas, I thought life was going to be different. Leo Cardenas, I haven't stood like you are standing, the beginner's stance, in over three decades, and yet I still don't know shit. I thought I'd fail at first but learn and learn, perfect my stance, start hitting ropes all over the yard. It hasn't happened that way, and sometimes I wonder if those few times when I really connected are all behind me, the rest of my days echoes of today, when I walked down Iowa Street in the cold gray afternoon punching my head. Glenn Abbott

2007-11-20 04:53

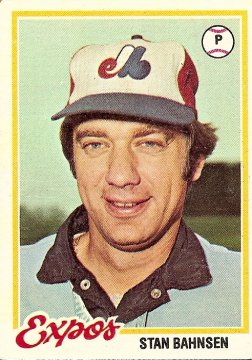

Stan Bahnsen

2007-11-16 08:16

I know now that the word avuncular means with uncle-like affection, but for some time I based my understanding of the word solely on the sound of it, which shared both the soft and fevery V sound of viral and the general quarantine-ward feel of tubercular, e.g., "I'd stay clear of that guy. The chronic, rasping cough, the clammy skin, the bloodshot eyes. He's gotta be avuncular." The initial misconception never entirely disappeared, and to this day my perception of avuncular contains traces of my original misunderstanding. I realized this when avuncular was the first word that came to my mind when I looked at this 1978 baseball card depicting a friendly, uncle-like, faintly unseemly, and perhaps slightly contagious Stan Bahnsen. Stan Bahnsen had a 133 and 135 won-loss record at the time of this strange photo, which seems to me, based on the slope of his shoulders and the unusually relaxed, familiar expression on his face, to have been taken by Stan Bahnsen, his unseen arms outstretched and pointing a camera back at himself. I can't explain the blurry and bizarrely uneven background in the picture, but perhaps it is a hurried doctoring job by Topps, commissioned at the very last minute to cover up the original backdrop of the picture, which I can only infer from the leering undercurrent in Stan Bahnsen's grin to be lowlit, illicit, boozy, malarial, the kind of faroff place where an aging avuncular hurler in a marshmallow-pale Expos cap might go to enjoy a stage show involving the ejection of ping pong balls from groin-related orifices. Mike Tyson

2007-11-14 10:51

I knew enough about the low-paying young adult nonfiction book racket to know that sometimes hard-working editors that had received unusable manuscripts from contracted authors had to hurriedly ghostwrite entire books without getting any authorial credit. Maybe my name had gotten pencilled in and the editor I knew or some other editor had scrambled to hit the deadline by throwing the book together and then, while racing with the manuscript to the local FedEx, had slightly altered the pencilled-in author name by adding an "ua" to the first name, a couple middle initials, and an extra "l" in the last name. The discovery of this Other (did D.G. stand for "DoppelGanger"?) gave me a sort of sour feeling. I wonder if former Cardinals utility infielder Mike Tyson, shown above in a creased, smeared 1974 card, felt something similar to that when he started to understand that his own name was being eclipsed. If he did, it's possible, oddly enough, that the feeling wasn't altogether new. Note the cartoon on the back of his 1974 card: In other words, it seems likely, given the overwhelming popularity of a certain 1976 Sylvester Stallone film, that—long before the other Mike Tyson—the chipmunk-cheeked Mike Tyson shown here was ribbed by his Cardinals teammates for sharing a name with a boxer. Or maybe not. Who knows? All I can really say for sure about any of this is that if there actually is someone out there named Joshua D.G. Willker, I hope I never meet him. He sounds like a douche. Warren Brusstar

2007-11-12 11:35

"Uh, Warren, that chick from last night," a teammate said a few moments prior to the snapping of this photograph. The teammate was standing just behind the photographer. The photographer was fiddling with the settings on his camera. "Which one?" Warren Brusstar said. He was already in a somewhat brusque, irritable mood. Here he was, the member of a championship team, the 1980 Phillies, maybe the greatest championship team of all time, considering the Phillies' 97-year title-virginity preceding 1980, and he still had to have his baseball card picture taken in such a remote, inglorious location that the photo would stand as quite likely the only baseball card in history to include so much as a single automobile. In all the many years of baseball cards even the most mundane images had been kept at something of a remove from the everyday existence that most of us slog through. Was not baseball a world away from the world, a bucolic paradise, a sanctuary of growing green? And yet here was Warren Brusstar, World Series champion, standing within sight of not one but two rattling rustbuckets. Where was his verdant baseball card eden? It was unprecedented. It was bullshit. "You know, heh," the teammate finally stammered. "The t-tall blonde you, uh, that you took out to the parking lot for a . . . for a few." "Oh, yeah," Warren Brusstar said. His expression began to soften. "I told her I wanted to show her my fine Corinthian leather." He started to smile at the memory of what had happened in the backseat of his Chrysler. Unfortunately, the photographer wasn’t quite ready to snap the picture. "Well, I don’t know how to tell you this," the teammate said. "Tell me what?" Warren Brusstar said. The teammate coughed into his fist. He muttered something inaudible. "What the hell did you just say?" Warren Brusstar said. The teammate looked past Warren Brusstar to the station wagon in the distance. He took a deep breath. "Say cheese," the photographer said. "Warren," the teammate said. "She’s a dude." Tippy Martinez

2007-11-09 07:58

During my American League East childhood in the 1970s and early 1980s, the Yankees rose to the top and fell, the Red Sox rose almost to the top and then fell, the Brewers rose from the middle up toward the top, the Tigers drifted around the middle while showing a few hints near the end that they might be preparing to rise, and the Blue Jays fell or rose, depending on your metaphysical bent, from nonexistence to the bottom, where they kept the Indians company. Only the Orioles escaped those years unscathed by ineptitude. They were always dignified contenders, somehow above both the mediocrity gripping the also-rans padding the lower ranks of the division and the ugly angst and anger surrounding the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry. I always kind of liked them. How could you not like a team that would often handle a late-inning crisis by turning to a guy named Tippy? The Orioles lacked the star power of the Yankees and Red Sox, and even when those teams began to crumble the bearded, swashbuckling Brewers swooped in to take their place as the contender with the charisma. But the Orioles almost always had the most complete team, with strong defense, good starting pitching, some speed, good power hitters in the middle of the lineup, a skilled, versatile bench, and, perhaps most important of all, an excellent bullpen. They contended nearly every year, but during the years when I was paying the closest attention they never made it all the way to a World Series championship. They did finally win it all in 1983, a couple years after I'd stopped collecting cards and caring so much. I don't know when they started to believe it was their year, but a good guess might be after a game on August 24. Going into the 9th inning that day, the Orioles trailed the Blue Jays by two runs, seeming to be on the brink of falling further behind the division-leading Brewers. But the Orioles scored two runs with a scrambling, bench-depleting rally that left them out of catchers: They had to send utility infielder Lenn Sakata behind the plate. Meanwhile, outfielders John Lowenstein and Gary Roenicke were forced into service in the infield, at second base and third base, respectively. I'll conclude my appreciation of Tippy Martinez with the rest of the game (courtesy of baseball reference.com), which started the Orioles on an 8-game winning streak that catapulted them into a division lead they would not relinquish. Please pay special attention to how Tippy Martinez recorded what would turn out to be the Blue Jays' final three outs, and how in the bottom of the inning Tippy's overmatched catcher showed his gratitude:

Ed Ott

2007-11-07 04:38

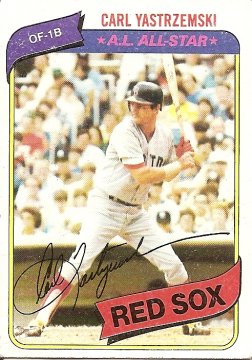

The Yazmobile Good feeling, In 2004, the day after the parade, my brother and I drove from his in-laws’ house in Brookline, where we were both staying, to Fenway. I forget why. Maybe to buy a couple souvenirs, maybe just to bask a little longer together in the glow of victory before we went back to our separate lives. On the way there, another driver passing us on the right lay on his horn and leaned his face out his window. He was about our age. "Yazmobile!" he shouted, beaming. I didn’t want the good feeling to end. My brother and his wife had to get back to Brooklyn. It was Halloween, and their route home was back through the Bronx, where anyone in the mood for a little Halloween car-pelting would be sure to enjoy a target festooned with red and blue signs with Red Sox lettering singing the praises of victory and Yaz. My brother’s wife wisely instructed my brother to turn the car back into a nondescript gray sedan. I still have the main Yazmobile banner, folded up and stored in a plastic container with other personal keepsakes. I like to hold onto things like that, especially now that I’m older and have had so many things like that disappear that it makes me wonder if I would still have Carl Yastrzemski’s autograph had he ever written back to me. I think I would still have it, but who knows? Sometimes it seems as if even things you make a point to hold onto slip away when you’re not paying attention. Maybe this is one reason why my midlife crisis has taken the form of paying an insane amount of attention to my childhood baseball cards. It’s a way to hold on, I guess. The card at the top of the page is one of the very few cards I have from my last season of buying them, 1981. A couple years earlier, during our annual summer visit to see him in New York City, my father had taken my brother and me to Shea to see the Mets get pummeled by the Pirates. Before the game several Pirates ambled over to the stands and signed autographs. My brother and I got in on the action, our very first real contact with the world we’d been worshipping for years. I don’t remember which of us got which autograph, but one of us got Omar Moreno and one of us got Ed Ott. It was a good feeling, holding the pages that held these somewhat random but still godly names. But my point is I don’t know what happened to those pages. Anyway, the day after the parade, as the former Yazmobile was heading south, I was on a plane bound west, to Chicago. The plane got delayed for a long time on the runway. I had a commemorative Sports Illustrated celebrating the Red Sox, and even though the lights in the cabin were on low I managed to kill some time leafing through it, revisiting the long history of the team from their early successes in the dead-ball era all the way up through the end to the 86-year championship drought. In the magazine, as in almost every printed version of the team’s story, the drought was referred to as a curse, a curse that began when the team sold its star, Babe Ruth, to the Yankees. There was a photo of the Babe in the magazine looking young and thin in a Red Sox uniform. The picture made me happy. The runway delay went on so long I gave up on finding any unread tidbits in the magazine. I put it back into the holder on the back of the seat in front of me. I don’t remember quite how we started our conversation, but I began talking to the woman beside me. She was a soft-spoken woman in her 40s who worked as a remedial reading teacher. Her name was Anita. We talked about where we were going (we were both going home, she to Nevada by way of Chicago) and about what had brought us to Boston: me for the parade, she to visit her daughter. Eventually the delay went on long enough to allow those facts to expand into deeper stories about our lives. She learned that my trip to see the parade was in some ways a trip to infuse my relationship with my brother with a booster shot of joy. I learned that her daughter was working as an intern for the Red Sox. And then I learned that her daughter had been able to get the internship because she was the great-granddaughter of a certain former Red Sox player. "My husband is Tom Stevens," Anita explained. "Babe Ruth’s grandson." Ever since I wrote a book called Classic Cons and Swindles, I have been on the paranoid lookout for someone planning to put one over on me. So it occurred to me that the woman was a professional grifter who had seen me leafing through my Red Sox magazine and had then tailored a way to get me awestruck and vulnerable for some sort of fleecing. I held onto this faint suspicion even as the warm feeling between the two of us grew with her family stories of Babe the doting, tender family man. But I didn't need to have worried about a set-up. Sometimes these nice things just happen, I guess. As it turned out, Anita never asked anything of me. But she did give me her address and urged me to write to her mother-in-law, Babe’s daughter Julia, who lived with Anita and Tom Stevens in Nevada. "Sometimes it takes her a little while to respond, but she loves getting mail," Anita said. A few weeks later I did write to Babe Ruth's daughter. I told her that I had been moved by her daughter-in-law’s stories of Babe the loving father. I told her that my wife worked in a group home with children who had grown up with little or no parenting, as Babe had, and that his ability to be a caring parent after growing up that way seemed to me as big an achievement as any of his miraculous feats on the diamond. In some ways the letter was like a bookend of the letter I’d written decades before, to Yaz. I’m still waiting for a reply to that earlier letter, but within a few weeks of my letter to Babe Ruth’s daughter I got a brief, gracious letter from Nevada, thanking me for writing and wishing me the best. I framed the autographed picture she enclosed with the letter, and even to this day it has the ability to make me feel as if I’m hanging on to that good feeling just a little longer... Carl Yastrzemski, 1981

2007-11-05 12:03

Chapter 5 (continued from Carl Yastrzemski, 1980) OK, I don’t actually have a 1981 Carl Yastrzemski card. As I’ve mentioned before on this site, in 1981 my card-buying dropped off precipitously. I can’t really remember why this happened, but it probably has a lot to do with the fact that my older brother had stopped collecting cards by then. Also, I had just slammed into puberty, so I had other things on my mind. And if that’s not enough, 1981 was also the first time a player strike wiped out a huge swath of games during the season. Unlike the later player-owner standoff, in 1994, baseball was able to return in time for the World Series, but everything seemed a little flimsy during that postseason, as if the proceedings were occurring under an asterisky mist. To that point I had been drawn to baseball in large part because it had been devoid of ambiguity for me, so things never quite seemed the same after the season where everything only sort of counted. I stopped gathering Cardboard Gods, but I never really let go of some of the dreams that had gone hand in hand with that gathering. One of them was that Yaz would acknowledge me, that he would acknowledge the letter I’d sent him, that he'd somehow hear my praise and the praise of all the other Yazites and break into a smile so wide as to banish sadness forever. Another was that the Red Sox would someday win it all. The picture above is of course from the parade celebrating the attainment of the latter dream. That’s my brother in his just-returned Yaz hat, a piece of victory confetti dangling from the misshapen brim. You can see by the figure at the left that there are duckboats passing by. We must have decided to break from our frenzied cheering to take a picture of one another (I also have a matching shot of me) during one of the happier moments of our lives, the conquering heroes finally riding past, almost close enough to touch. I had heard that former players would be riding in the parade, and I hoped that Yaz was among them so I could cheer him as a champion. But he wasn’t there. In fact, in late October 2004 he was little more than a month removed from losing his only son, Mike. Yaz appeared the following April at Fenway to raise the championship banner with Johnny Pesky. I still hadn't heard about his son's death, so as I watched the banner-raising I wondered why Yaz seemed so subdued. The days of suffering are over, I wanted to tell him. Come on, Yaz! Yaz threw out the first pitch of the World Series this year, and he seemed a little happier, surrounded on the mound by some of his teammates from the great 1967 pennant-winning team. All in all the 2007 championship season was less freighted by the weight of history. This element seems to have extended to the parade, which by all accounts was a buoyant, laughing celebration, best defined by the jigging relief ace and free of thoughts of the past and of loved ones gone beyond and tears of gratitude and joy. I wasn’t there for the parade this time. If I lived closer I probably would have gone, but in some ways I’m glad to have the parade of 2004, my brother by my side, as the only one in my memory. After the moment captured by the photo above we cheered some more for the last duckboats, then we walked around dazed for a while. I remember seeing a pack of shirtless teenaged boys stagger past with a crudely rendered cardboard sign that read "Show us your boobs!" I bought a championship T-shirt from some guy with a garbage bag full of them. We passed a big guy in a Pedro shirt and an afro wig saying into his cell phone, "So you get the bail money yet?" Eventually my brother and I found ourselves packed in with a crowd on a bridge stretching over the Charles River. We yelled as the duckboats floated by beneath us and then moved up the shore, a continual roar following them from the throngs at the water's edge and echoing across the river and up into the cold gray sky. Winter was on its way, but for the first time in our lives we were going into it as champions. The sound of the roar rippling up the shore for the 2004 Red Sox sounded exactly like the first crowd-prayer I’d ever heard, that one long unbroken syllable, as if we were all yelling as loud as we possibly could for Yaz. Carl Yastrzemski, 1980

2007-11-02 06:32

The Yazmobile Chapter 4 (continued from Carl Yastrzemski, 1978) Here is the baseball card I love the most. It's pretty beat up. I handled it a lot as a kid, then as an adult had it taped to the wall by my writing desk for many years. That's how you've got to do it, I told myself, looking at the card. Dig in. Stay balanced. Wait. Hang in there. Wait. Be quick when the right pitch comes. The statistics on the back of the card provided further instruction. The tiny type, the many seasons, the stunning number of hits, the even more stunning number, hidden but revealed by simple subtraction, of outs. You've got to work at it for years. You've got to fail thousands of times. You've got to keep getting back in there, each time as awake and alive as you were your very first time. I must have looked at the card thousands of times. I don't know if any of it rubbed off on me. Eventually I put it back in with the rest of my cards, but then four years ago I made a wall-hanging by bordering a copy of the front page of the October 28, 2004, Boston Globe with the holiest of my Cardboard Gods, the Red Sox players from my childhood in the 1970s, and this card found a place in the upper left hand corner. It was a crude piece of craft-making, the kind of thing a little boy would do. But I guess I wanted to hold on to the feeling of late October 2004 a little longer, the feeling of being a little boy again. By October 2004 I had moved to Chicago. My decade or so of trying to cling to boyhood and hide from adulthood by sharing an apartment with my brother had come to an end a few years earlier, those first years apart painful for me, as if below the surface entangled roots were being torn. Our stuff had been mixed together for years. Now some of my stuff was missing, and other stuff that I did have made me feel guilty to have it, because it wasn’t mine. I’m reaching for metaphors here, but there actually were some real objects involved. I ended up with some of my brother’s novels; he ended up with some of my comic books. I ended up with an autograph made out to the both of us from cartoonist Daniel Clowes; he ended up with an autograph made out to the both of us from Steve Balboni. But of all the things I ended up with that weren’t mine, the one that made me feel the guiltiest was perhaps the one that had cost the least. I’d been with my brother when he’d bought it, at a souvenir store outside Fenway a couple years after Yaz retired, a closeout item, the price slashed: a white painter’s cap with the word Yaz on the front and various career achievements listed on the sides. Somehow over the years of living together in New York I’d appropriated the cap (the cap is mentioned elsewhere on this site in a description of a grisly fight-filled Opening Day at Yankee Stadium), and it had been among my things when I’d moved off on my own. I wore it to a Red Sox bar in Chicago to watch the fourth game of the 2004 World Series, and one of my favorite memories of that beautiful night was walking through the packed bar after the final out, on my way to take my first piss as a champion, and accepting the Yaz-based congratulations of other Red Sox fans who patted the top of my Yaz-capped head and shouted "Way to go, Yaz!" or "We fucking did it, Yaz!" or just, simply, "Yaz!!!!!" It was a good moment, but since it was my brother’s cap it should have been my brother’s moment. I tried to assuage my guilt about this with the fact that I'd soon be handing the cap back to my brother; we had decided to meet in Boston for the victory parade. I don't know if my brother feels cheated out of his own rightful Yaz-cap moment, but if he did it didn't stop him from manufacturing his own Yaz moment, festooning his car with Yaz-related signs and banners in preparation of the drive from his house in Brooklyn to the parade in Boston. He had decided, in short, to turn his car into The Yazmobile: (to be continued) |