|

Monthly archives: January 2009

Dave Skaggs

2009-01-30 07:00

(continued from Larry Hardy) Chapter Four I never made it to Galicia to wander the ghostly grounds of the vanished gas-chambered shtetl thinking tragic historical thoughts about my ancestors, or whatever the fuck I'd been hoping to do. Instead I started seeping back westward not long after having a bleak vision of universal loneliness and alienation in a town in East Germany called Schwerin. I’d been trying to hitchhike farther east than Schwerin, to Berlin, and from there to points even deeper into the grim mysterious regions beyond the recently lifted Iron Curtain. But after standing on the shoulder of a highway in Hamburg for a very long time without even a nibble I had begun silently chanting the mantra of the stranded: Anywhere is better than here. Anywhere is better than here. Finally, a car pulled over and the driver said a word I'd never heard: "Schwerin?" He could have said anything. I got in the car. *** At that very moment, late October 1990, Dave Skaggs may have been playing or getting ready to play his last games of professional baseball. According to BR bullpen, Skaggs appeared that year in the Senior Professional Baseball Association. The short-lived winter league, loaded with former stars and journeymen from the Cardboard Gods era, shut its doors in December of 1990, but not before Skaggs and his teammates on the San Bernadino Pride battled their way to a record of 13 and 12. He hadn’t played in the major leagues for ten years, since 1980 when he appeared in two games for the Baltimore Orioles and 24 games for the California Angels. I don’t know if he played in the minor leagues after that, because baseball cards only show the minor leagues as a prelude, never as an aftermath. The fact that Skaggs was available to limp around for meager pay in a doomed geezer winter league suggests that he probably didn’t instantly leap from his 1981 release by the Seattle Mariners (who had signed him a month earlier but didn’t need him because they already had Terry Bulling) to a spectacularly successful career in some other field. He probably kept playing ball. Perhaps he even stuck around long enough to gradually make his way back down the minor league ladder he'd spent several hard years climbing. Back to Rochester, where he’d toiled in 1976 and part of 1975. Back to Asheville, where he’d toiled in 1974 and part of 1975. Back even earlier and lower, to the team he played for in 1973, five years into his professional career and still a million miles from the majors. Back to Lodi. *** The driver let me off at an exit ramp in Schwerin. He must have pointed me the way to go, but I got confused instantly, and for a very long time I wandered lost in a landscape only slightly more habitable for a pedestrian than the surface of Jupiter. Here’s what I wrote in my notebook the next day: I was trying to walk to the youth hostel. I took a wrong turn and walked two miles in a nowhere direction. The road was flat and cracked and stretched into afternoon hazy visions of steel industrial plants, the smokestacks breathing streaks of dirt into the sky. The cars that passed were mostly broken down Russian cars with no catalytic converters, so their foul air was noisily blasted in my face until I was light-headed and achy and felt enclosed. The pack was heavy and beginning to dig down into my shoulders. The landscape was gray and barren. Earlier I had walked past a huge Russian Army barracks, a truck of dark-eyed soldiers passing me into its entrance. Soon they would all abandon the hulking stone buildings to go back to their country to starve. I was walking on the road and thinking not only of my own nowhere going but the whole earth wrapped as it is in cracked, nowhere going roads and abandoned useless buildings and towers and potatoes falling and rotting to the ground as millions starve in muddy hovels in the cold. This was the black end. I was saying to myself, "I will go home, I must go home," and as I said it I thought of the massive half-realized failure of my own life and how I couldn’t speak to anyone ever from shame and how I would lead a mundane, death-surrounded life and never really know home. *** If I lost connection somewhere, that implies that somewhere I had connection. If I find myself hoping to take the next train back to where I lived, that implies that, sometime before setting off in 1990 to find my life and finding instead that the whole wide world was Lodi, there once was a place where I lived. I can’t put my finger on any map of where that might be, except to locate personal versions of ghost towns, just as I can’t put words to that connection. But I know what that connection feels like. It feels like holding a piece of cardboard in my hands and pronouncing the name on the card for the first time, the player brand new to the Cardboard Gods, his name one that by its strange and biting sound alone instantly scored an indelible groove in my 10-year-old brain: Dave Skaggs. The guarded, menacing face on the 1978 card, his first, fit the name, as did the fading light in the blurred background behind him, dusk coming on in the anonymous nowhere of Dave Skaggs, Skaggs who knows the nowhere well and grips the bat and glares, ready for trouble, for grim toothless tormentors in scars and rags, Skaggs mean and lonely, hopeless and brave. Skaggs never nobody. Skaggs unbowed. (to be continued) Larry Hardy

2009-01-28 09:21

(continued from Tom Brunansky) Chapter Three As I experienced it, the Red Sox were swept out of the 1990 playoffs instantaneously. I barely had time to dry my eyes from my emotional envisioning of the Brunansky catch before buying another Herald Tribune to find that they had been flicked aside in four quick games by the Oakland A’s. Whatever seems like it might be something is really just nothing in a cheap, unraveling disguise. But don’t grip too tightly to that glib shard of nihilism, because the opposite is also true. Or neither is true. Who knows? A few days after my team’s disappointing el foldo, I ended a long passage in my battered travel notebook this way: There is a holy hum that runs through everything, I am trying to believe. *** This is Larry Hardy’s only baseball card. The back of his card shows that he progressed in a straight upward line through the Padres system, with just one exception, one tiny and seemingly insignificant hiccup that ended up being a much more accurate harbinger of things to come than the otherwise upward-pointing line of his minor and major league stats as of 1974. This hiccup occurred in 1971, his second year as a pro player, when he was sent back to the Padres lowest-level minor league team after moving up and away from that team at the very tail end of the previous season. The low-level team he was sent back to was located in Lodi. *** I don’t know where I lost connection. I can tell you that as my years in college went on, I had fewer and fewer friends, mainly because all of the guys I’d started with in a cloud of bong smoke had eventually dropped out or been asked to leave or, in a couple rare cases, had continued their nondescript education by transferring to another anonymous diplomatorium. With them gone, I spent more and more time in the library. I became a passionate student. Perhaps the best path for me to have taken right after college would have been to continue straight on into grad school, to keep wrasslin’ those books. But I had it in mind that I needed to go out beyond the walls of the library and experience life like the heroes of all the stories I loved. I wanted to be a hero. I wanted to travel up out of this world to the world of the gods and return with the holy hum coursing through my body and springing from my fingers. *** In his debut season of 1974 Larry Hardy set a major league record. It was not a negligible, trivial mark, either, no mere accident or oddity, but a significant single-season achievement that at the very least illustrates that Larry Hardy mattered, at least for one year: He pitched in more games than any rookie ever had. His name, which had never been called by a major league manager, was suddenly called more than anyone in the league aside from the name of another reliever, Mike Marshall, who was in the midst of appearing in more games than anyone ever has, rookie or otherwise. "What’s the kid’s name? Right, he’s not really a kid anymore, but you know who I mean. Hardy? Get him warm." "Well, this one’s out of reach. Get me Hardy." "Guess things can’t get any worse. Might as well get Hardy going." "Who’s left out there. Just Hardy? Christ. [Long pause.] Get him up." Yes, Larry Hardy wasn’t particularly effective, getting knocked around to the tune of a 4.69 ERA that was over a run higher than the league average, but he did get credit for 9 wins against just 4 losses, and this for a team that won just 60 games while losing 102. Larry Hardy mattered. Larry Hardy won. Things were looking up for Larry Hardy. Why then the expression of apprehension and mute alarm, as if Hardy was watching nothing shed the last of its cheap disguise? Tom Brunansky

2009-01-26 07:47

(continued from Terry Bulling) A large question mark hovers near Tom Brunansky as he completes what appears to be a meaningless play. This is his last baseball card. Eventually a ballplayer loses connection to the only world he knows. The question marks grow bigger. I guess they eventually take over. *** I landed in Frankfurt in the fall of 1990. The previous year, I’d spent a few months studying in Shanghai, where I lived in a foreign students dorm. One of the other foreign students, a German named Sven, was standing there in the early morning in the Frankfurt airport. We blinked at each other, our mouths open. A few moments later, before we'd even had a chance to process the incongruence of the situation, we were joined by the person Sven had come to the airport to pick up, his girlfriend, Ema, an Italian woman who’d also been a student in Shanghai. I had been friendly with but not particularly close to either of these people. Ema, for example, had always thought my name was Scott. "What the fuck is Scott doing here?" she said. *** During what turned out to be Tom Brunansky’s last season, 1994, he was traded from the Brewers to the Red Sox. The back of this 1995 card combines his statistics for the two teams, something that was never done in the cards of my youth. You can’t know where one period ends and the other begins. Was he doing atrociously for the Brewers? Were things looking up for him on the Red Sox? Was he going to be coming back for another year? Would there, considering the ongoing labor troubles, even be another year? Questions. Nothing but questions. *** The three of us stood there with idiotic grins. I fought back the urge to apologize. I felt large and malodorous, an intruder in someone else’s dream. My memory is that they drove me to Sven’s town, Heidelberg, dumped me off at the youth hostel, and went on their way, but yesterday I dug through my old notebooks (always a demoralizingly exhausting task) and discovered that they must have allowed me to be a third wheel for a little while. There was a meal in a cafeteria with sausage and mealy mashed potatoes, some moments in a department store where I kept fearing that I'd knock over shelves with my backpack, and a walk through the woods to the ruins of an amphitheater where the Nazis used to mass, the dirt road to that site leading past a tavern where the drinks were free on Hitler’s birthday. There was also a moment at some point when I temporarily separated from them, and I sat alone on a bench on a hill and heard bells ring for several minutes from every corner of the ancient city below me. I got tears in my eyes. I figured it must have some meaning, some kind of a connection to old joy. But when I rejoined Sven and Ema for the last time before heading on my way, I asked him about it, and he just shrugged. *** You can tell on the back of this card that Brunansky had come to the Red Sox once before, in 1990, also in the middle of the season, and as in 1994 this cheap flashy card combines his stats for 1990 into one line. You can’t estimate when he left the Cardinals for the Red Sox, nor see if he helped his new team with a hot streak down the stretch. If there’s a story about 1990, you won’t be able to connect to it in this card. But maybe that’s the story about 1990. Whatever it is, you won't be able to connect to it. *** After Heidelberg, I went south, toward a resort town I’d read about back in America, while leafing through a book in a Barnes and Noble on working abroad. I figured if I could find work as I traveled I could make the aimless trip last longer, or perhaps even last long enough to take on some kind of shape, some kind of a purpose. I’d even gotten my passport stamped with visas to some Central European countries that were just then opening up to the west. I was hoping to work a little, travel a little, work a little, travel some more, and eventually find myself entwined in some kind of inescapable narrative of mystery and discovery. Some kind of story. But everything I came upon, even when it seemed particularly significant, dissolved almost as soon as it appeared. I don't even remember saying goobye to Sven and Ema. *** After a couple days in the resort town of walking up and down steep hills with other foreigners and finding no work, I started seeping back north and east, vaguely toward my grandparents’ old region, Galicia. (I never got there.) I stopped for a couple days back in Frankfurt, where I bought a Herald Tribune and discovered that my team, the Red Sox, had just experienced the most exciting end to a regular season in the history of the franchise. They had needed a win on the last day of the season to get into the playoffs, and they got it with a game-ending spectacular diving catch of an Ozzie Guillen line drive by Tom Brunansky. I imagined the whole scene, heard Fenway Park rocking with cheers. I can't be sure, but I think the small recap of the game was accompanied by a photo of Wade Boggs beaming, his arms raised in triumph. It seemed significant. The start of a story. THE story. "This is the year," I said. I had tears in my eyes. (to be continued) Terry Bulling

2009-01-22 08:26

Chapter One This was Terry Bulling's first baseball card, and it probably seemed for quite a while as if it would be his last, since he dropped back out of the majors for several years after his short stint in The Show in 1977. But he resurfaced in 1981 with the Mariners, and in 1982 caught Gaylord Perry’s 300th win. In the blog of cheating-in-baseball expert Derek Zumsteg, Bulling is featured prominently in an anecdote that, if accurate, sheds further light on the extent of Bulling’s famed battery-mate’s desire to gain a competitive edge. According to the anecdote, Bulling reported that "Gaylord coats his entire body with Ben-Gay before the game, and when he sweats during the game his entire uniform becomes a big greaseball. He can touch any part of his uniform to throw a greaseball. The umpires can check him all they want, but Ben-Gay isn’t illegal and there’s nothing they can do about it." I imagine that Terry Bulling, or Bud Bulling as he was apparently more commonly known, was the perfect guy to catch Perry’s 300th win. For one thing, he seems to have felt at worst neutral and more likely even a little amused by Perry’s unorthodox methods. Also, as a little-known journeyman he presumably didn’t have the authority to impose any kind of a plan on the game, having to defer to the slippery gray foul-smelling eminence on the mound. According to the Sports Illustrated article about Perry’s 300th win, the pitcher shook off Bulling’s signals constantly, something that I imagine was done by Perry more than anything to add even more ambiguity to his pre-pitch ritual stew of tics and shrugs and scratching and licking and rubbing, thus further crawling into the mind of the batter, who was already jittery over the prospect of loaded pitches dipping and diving in all directions. But I can’t see Perry constantly denying the choices of, say, Carlton Fisk or Johnny Bench. If he did, they’d eventually come out and slug him, or at least try to. (I'm not sure happens when you try to punch a guy covered in slime.) But Bulling just went with the flow, the perfect receiver for Perry’s unpredictable junk. Who better to roll with whatever comes his way than a journeyman? A journeyman knows you’re never anywhere very long, and even if you try to imagine something connecting one fleeting moment to the next the only path you’ll be able to trace will be irrational, spasmodic, inane, the ungodly flight of a doctored pitch. Furthermore, a journeyman knows that even when you stand still you’re part of a greater unstoppable movement. This phenomenon underscores the Creedence song "Lodi," one of my favorites, in which the singer laments the disintegration of his dreams while stranded in a nowhere town. I thought of that song when I perused the back of this Terry Bulling card. Bulling spent his first three years after college in one minor league town, something I don’t think I’ve seen on any other card. He didn’t even split a season and spend some time elsewhere, just stayed in a place abbreviated on the back of this card as "Wisc. Rapids." It’s a place-name that implies swift movement, yet there Bulling stayed, year after year on the lowest rung, and at a time in his young life when years must have seemed long instead of the quick blurs they become as you get older. Those are hard years, the first years after school. They were for me, anyway. There certainly weren’t any major or minor league teams of any kind, literal or figurative, knocking on my door. I had no skills, no connections, not even much ambition beyond a hazy collection of vague, ridiculous, impossible hallucinations about a future involving writing, some shattering moment of lasting spiritual enlightenment, rooms full of people cheering for me, and fucking. My first year out of college was going to be spent in Shanghai, teaching English, but then I got a rice paper letter from my girlfriend over there, saying that she’d met somebody else, so I spent the money I’d saved up for my ticket to China on a trip to Europe. I tried to do the trip as cheaply as possible so I could make it last. The first step in that strategy was to use a service that got you onto random flights that had empty seats. You couldn’t pick the city you wanted to go to, just a general region, then you’d go to the airport and hang around until they could shove you onto an unpopular flight. This was just after the Berlin Wall came down, so I had a sketchy idea that I’d eventually make my way beyond the vanished Cold War divider to the Central European region my paternal grandparents fled from in the early 1900s, Galicia. The closest I could get using my mode of cheap air travel was Frankfurt, Germany. I didn’t know anyone there or speak the language or have any plan on where I was going to spend the night. The plane landed in the early morning, and as I was walking down an airport hallway after exiting the plane my transcontinental daze slowly gave way to a mixture of terror and self-hatred. I was about to start punching myself in the head as inconspicuously as possible. But then, in one of those rare times when the absurd illogic of dreams spills over into waking life, one of those moments when you can almost see the gleam of some beyond-law substance on the doctored pitch of your life, I ran right into someone I knew. (to be continued) Bill Russell

2009-01-20 06:07

The tough way: Get on the field. Assume the proper crapping-in-the-woods crouch. Grimace a little if you want to, like Dirty Harry. Say in your mind: Hit it to me. If the ball takes a bad hop and thumps your chest or clips your jaw or drills you in the stones, pick it up and make the play. Spit and punch your glove. Extra points for spitting a tooth. Later, at night, sleep deeply. My way: Imagine, before even taking the field, all the bad hops a ball could make. Take the field tentatively. Pray the ball is hit to someone else. Later, at night, stare at the ceiling, wide awake and cringing with regret. Of course I am speaking metaphorically, since I haven’t been called on to field an actual grounder for decades. What have I been doing instead? Nothing much. Some writing. That’s the supposed focus of each day and has been for a long time, but in fact most days I fail to take the correct stance, the stance that will put me in the path of whatever is hit my way, one way or another, even if it causes me pain. Instead I move out of the path of the ball and stab at it. If it gets by me, well, whatever, there’s always tomorrow. George Brett, 1978

2009-01-16 07:16

It is fucking cold here in Chicago, Illinois. Twelve degrees below zero as of this moment. I haven’t been outside since yesterday, when I put on two pairs of socks, long underwear, my thickest pair of jeans, three shirts and a sweater, a parka, hiking boots, gloves, two wool hats, and a scarf the size of a blanket and walked a few blocks to slide the DVD of Pineapple Express through the return slot at the video store. The digital bank clock by the video store reported that it was minus five. The walk there wasn’t so bad, but on the way back I was walking against a stiff wind, which I swore at through my unraveling scarf-blanket as the few inches of exposed skin on my face became increasingly painful. But worse, really, is the oppressive monotony of being inside all the time, especially in an apartment with very poor insulation. I’m in the apartment’s office right now, which is above the unheated stairwell. The wood floor feels like chilled metal, and cold air pushes through the two windows. I’m wearing a wool hat, long underwear, flannel pants, two pairs of socks, slippers, two shirts, a sweatshirt, a sweater, and a gortex vest, and I’m still chilly, especially in my hands, which I have to rub and blow on pretty constantly, like Bob Cratchit. The heat comes on every couple minutes, producing images of cartoon dollar bills flying from my wallet. Our heating bills are going to put us into the poor house, which is probably even more poorly insulated. Or worse, we’ll be out on the street. My god. I’m glad I’ve got a roof over my head during times like these. Fantasy #1 But I wish I was in a place as warm and sunny as the one on this 1978 baseball card of George Brett. Of course, it’s hard to know for sure that it’s warm wherever Brett was when the picture was snapped, but it is inarguably sunny, and he is without a hat and doesn’t seem to be cringing against a stiff wind or wearing anything thicker than the thin blue polyester Royals uniform designed for the brutally hot Kansas City summers. I guess you could argue that some manner of wind is blowing Brett’s tousled golden locks, but I really think it must be more of a gentle spring breeze than a stiff chilly gust. So that’s where I want to be. Bathed in sunlight. The sounds of the game echoing across the warm green fields. I think what I’d do is lean back and close my eyes and angle my face right up at the sun and just listen. Reality #2 The worst cold snap I experienced occurred in Vermont in January 2000, the year I lived in a cabin with no electricity. I went to visit my aunt and uncle near the beginning of the cold snap, and couldn’t leave for a couple days during the worst of it because my car refused to start. Finally it coughed to life one morning when the temperature rose from instantly crippling cold to merely really, really cold, and I drove back to my cabin, first stopping at a K-Mart to buy thick opaque sheets of plastic to put up over my windows and another wool hat to add to the bulky collection on my head. When I got back to the cabin I discovered that everything I owned had frozen solid, including things that I didn’t know could freeze, such as toothpaste. I got a sputtering fire going in the little wood stove, using the shitty green wood that the owner of the cabin, a tense hippie with a reputation for fucking people over, had sold me, then I inexpertly plastered the plastic all over the windows using duct tape. I spent the remainder of the winter huddled over the wood stove, practically hugging it, because it never generated enough heat to warm up the whole cabin. I couldn’t really see anything through the plastic, but I had a vague idea of whether it was night or day, and I could tell by the wind rattling the birches and moaning through pines that it was cold out there, the kind of cold that would seem almost predatory if it weren’t so completely indifferent. Fantasy #2 I was ostensibly working as a teacher during that era, but by January 2000 my course load as an adjunct professor had dissolved to next to nothing, my only task being the sporadic tutoring in essay writing of a Vietnam vet with severe post-traumatic stress disorder who eventually stopped showing up for our meetings. But I still went onto campus every couple of days to the office I shared with several other adjuncts so that I could check the progress of my fantasy basketball team. It gave at least the tiniest shred of a shape to a life that had become almost utterly shapeless. I guess my life has more of a shape now, but I still start every day with a check of my fantasy team or teams. Right now all I’ve got going is a basketball squad in second-place in a thirteen-team league, but I think I did see some article just this morning on my way to check on my roster about B.J. Upton’s prospective slot in upcoming fantasy baseball drafts. I was excited by this, because this meant it is almost time for me to put together a pre-draft ranking list, which always proves to be an enjoyable way to kill some time. I’m not really sure why I find such things enjoyable. I do know that ever since I was a boy I’ve tried to dream my way out of my life and into a fantasy life revolving around sports, especially baseball. In 1978, the year I first held this sun-drenched George Brett card in my hand, I was well into a childhood consumed with imaginary baseball-related games around the house, games in which I would become someone else, or actually whole worlds of someone elses. I’d be every player on both teams and the crowd and the announcers, too. At the moment of victory I’d pitch to my knees in the back yard holding a whiffle ball bat or tennis ball or whatever else I’d been using and imagine I was the victorious long-suffering star, finally basking in the warm light of winning, and I’d pretend to cry. Reality #3 But the coldest I’ve ever been was not here in Chicago or in Vermont but one night while I was drifting randomly around Europe the year after I finished college. I had been in Essen, Germany, lazing around a youth hostel while I waited for the Grateful Dead to arrive in town for a concert. Unfortunately, the day before the concert I was told I had to leave the hostel because it had been reserved months before to house several teams of acrobatic teenagers from all around the globe coming to Essen to compete in an international youth trampolining contest. Evicted, I took a train to Cologne, arriving in the late afternoon. Both of the youth hostels I tried in Cologne were full. I guess I could have shelled out for a room in a hotel, but I don’t think I even considered that. I didn’t have much money, and more importantly I was obsessed with the idea that my money equaled time, as in the longer I could keep my little roll of bills alive the longer I could delay my return to the utter blank of my post-college life in America. So I went down to a park along the river with my backpack. Though it was November I didn’t think it was that cold, at least while the sun was still above the old-world steeple-marked skyline. I think I even imagined it might be peaceful. A night out under the stars! But as the night went on it got colder and colder. Pretty soon into it I had emptied my backpack of every last article of clothing I owned and wrapped it around my shivering body. I figured if I could fall asleep I could make the night go by faster, but I was never able to even so much as fall into a shallow ditch of unconsciousness for more than a couple minutes, at which point I’d wake up trembling and have to get up and do jumping jacks and wind-sprints. I also whooped and hollered, as if by using my voice I could somehow push back against a world that kept telling me I had to move. Fantasy #3 If I had lived a certain kind of life maybe by now I would have enough money in the bank to get the hell out of town when it gets really fucking cold. Perhaps I could even go to Fantasy Camp. This is where middle-aged dudes pay a bundle to exit the winter and play baseball in the warm sun against each other and against some of the major leaguers who showed up on the baseball cards and in the fantasies of the campers back when they were basking in the summertime glow of youth. I hope it doesn’t sound like I’m mocking such a thing, because, really, if I had money how better could I spend it than on such a thing as this? That’s the thing with these baseball cards I write about day in and day out. When I was a boy I fantasized about being a 24-year-old A.L. ALL STAR, a red, white, and blue shield on my card, the sun lighting my tousled golden locks, and now that I’m a middle-aged guy I fantasize about being a 24-year-old A.L. ALL STAR, a red, white, and blue shield on my card, the sun lighting my tousled golden locks. These cards are the unchanging fantasy at the center of the unraveling spiral of my years. So, yeah, more power to the Fantasy Camps, which feed into perhaps the single most enduring fantasy of American men that doesn’t involve a cheap funk soundtrack and grateful moaning. I don’t know exactly when the first Fantasy Camp opened, but I feel like I first started hearing about them around the time I was gripping onto my little wood stove for dear life during the year in the cabin. But in fact the first Fantasy Camp occurred several years earlier than that, in the sunny year of 1978, under the visionary leadership of none other than the late great Mr. Roarke. Turns out George Brett was on hand, along with fellow Cardboard Gods Fred Lynn, Tommy Lasorda, and Steve Garvey. Gary "Radar" Burghoff was there, too, on one of his last stops on his way out of the public eye and into the oblivion beyond Fantasy Island guests spots. As Mr. Roarke explains, Burghoff’s character is a guy named Richard Delaney who wants to be a baseball superstar. (Fittingly, at least from where I'm sitting, Richard Delaney has come to the warm, sun-drenched island of fantasies from that undoubtedly cold-as-fuck city of reality: Chicago, Illinois.) To get a peek at Delaney's fantasy, which is really all our fantasies, or even just to take a break from the cold and see some sunshine and warmth and to hear Ricardo Montalban demonstrate his greatness by the way he recites the words "baseball superstar," click here (thanks to Dodger Thoughts for the link). *** (Love versus Hate update: George Brett's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Lou Brock, '77 Record-Breaker in . . . (Yet Another) Nagging Question

2009-01-14 09:22

For you youngsters out there, here’s a checklist you can use to gain quick, enthusiastic entry into the baseball Hall of Fame:

If you have the first item checked off but have neglected to ensure the achievement of the second, you will not be greeted with open arms by Immortality. Consider Don Sutton, who had to wait through a few years of rejection by voters before getting into the Hall even though he had surpassed the magic number of 300 wins, his problem being a lack of a story with a hook (beyond, perhaps, his underreported status as a brave pioneer in the eroding of baseball’s unsaid yet staunch and enduring no-perm policy). Or, to address the "uncomplicated" element in the second checklist item, consider Mark McGwire, whose statistics are festooned with garish statistical baubles that would seem to put him on par with the greatest sluggers in the history of the game, yet who has gotten very scarce support from voters because the perception of his story is that it is covered in lurid, nauseating back acne, the kind of thing that most people instinctively turn away from and try to pretend they never saw. If you have the second item checked off but not the first, you might still be able to sail in on the first vote, but you probably have to be named Jackie Robinson or Sandy Koufax or have a similarly spectacular supernova-bright presence in your relatively short time in the spotlight. So really it’s safest to have both items checked off, which the man pictured here did with a paradoxical combination of relentlessness and quiet grace. He amassed over 3,000 hits to check off the first item on the above list and checked off the second item primarily by (as noted in this special 1978 baseball card) establishing himself as The Greatest Base Stealer of All Time. (He also deepened the hues of Greatness in his story by performing spectacularly well in World Series play.) A couple days ago Rickey Henderson, who supplanted Brock as The Greatest Base Stealer of All Time, also sauntered into the Hall on his first try, and many of the stories about his easy election mentioned his status as The Greatest Leadoff Man of All Time. I don’t know if Brock was also given that distinction upon his election, but I suspect that it at least came up in some retrospective reporting about his career. The prevailing perception of Brock was that he was one of the greatest of the greats (Bill James points out while compiling his own top 100 that Brock had a composite ranking of 63rd best player of all-time on the lists he consulted—The Sporting News; SABR poll; Total Baseball; Maury Allen; Honig and Ritter; and Faber), so it stands to reason that many would have ranked him as the Greatest Leadoff Hitter of All Time until the coming of the long and storied career of Rickey Henderson. With this in mind, I thought I’d play around with a few simple numbers of the guys that sprung to my mind as being among baseball’s greatest leadoff hitters. Be warned: None of the lists below account for era and park factors, and the lists, since they are based on statistical records, also exclude any leadoff hitters from the Negro Leagues (Cool Papa Bell probably foremost among them). Please don’t hesitate to be the first to bring up the name of some should-have-been-obvious guy I left off the list. (Some all-time greats, such as Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, and Joe Morgan, who would seem to be perfectly suited for the leadoff role, were excluded from the lists because they were more often—or in Morgan’s case at least throughout his prime—used as middle-of-the-lineup hitters.) Consider the following then as just a bit of superficial numbers-related playtime, perhaps its only merit being that it happened to stumble into further illustrating how high Rickey Henderson towers over other leadoff-hitting greats. With Henderson’s spot at the top as a given, then, and with the numbers below as mildly relevant party favors, I offer today’s nagging question: Who was the second-greatest leadoff hitter of all time? Games (The most underrated of all counting stats, in my opinion) Runs (What it all boils down to for a leadoff guy) Runs/game (A chance for short-timers such as Hamilton and Robinson to make up ground) OBP (The list that might have benefited the most from adjustment for era) Stolen bases (The leadoff-man list with all the bells and whistles) Stolen base percentage (And here’s where the great Tim Raines makes his move. Also, players with incomplete caught-stealing numbers were ranked by estimated place on the list; the deadball guys are near the bottom, cushioned only by the relentless out-maker, Rose, because I think anecdotal evidence points to high caught-stealing rates during those olden days.) Stolen base titles (I don't know, I added this category thinking it might benefit guys from low-stolen-base eras, such as Robinson and Ashburn. It didn't end up doing this, but I kept it in here so as to throw the likable Lou Brock a bone. . . . Believe me, I understand how far this whole exercise is from actual useful analysis.) Total score (This is the sum of the rankings, low score first; as alluded to before, I like how the biggest gap between any of the players is between Rickey and his closest pursuer. I think Jackie Robinson gets majorly shafted by my little game; because of his excellent OBP, plus his reputation as a ferocious competitor and smart, fast, and disruptive baserunner, I'm tempted to pick Robinson as the second-best leadoff man of all time. It's a tough call, though, because his career was so short. And speaking of short careers, I really don't know much about Billy Hamilton, but I think he's getting a distorted boost here by virtue of the relatively high OBP and steal numbers of his era. Eddie Collins also comes off well here, as the guy Bill James ranks as the 18th best player of all-time should, but you could argue that his numbers benefit from the fact that he played during an era diluted by segregation. Next on the list is a two-man tie including Craig Biggio, but Biggio's OBP and runs scored numbers were recorded during a long league-wide offensive explosion. With all that in mind, I think I'm still leaning toward the guy I was rooting for all along to finish second to Rickey in this exercise, Tim Raines, a man apparently lacking both of the checklist items mentioned at the top of this post, and the only man on the list who isn't in the Hall of Fame, or ensured of someday being in the Hall of Fame, or currently banned from entering the Hall of Fame.) Lou Brock

2009-01-13 05:52

Years ago, back when I lived in Brooklyn, I was staring at the ceiling, listening to the radio, and wondering if it was too early in the day to masturbate. The usual. It must have been a slow news day, because the radio hosts, a short-lived pairing of Suzyn Waldman and Jody MacDonald, started comparing current players to players from the past. I was roused from my torpor by the claim, made by Waldman, that Bernie Williams could hold his own in a comparison to Carl Yastrzemski. Enraged, I dialed the number that had been ingrained into me from years of lying around and staring at the ceiling and listening to the Fan. Unfortunately, the line was busy. I tried back a couple times. Each time my desire to actually get through waned a little more. Eventually my anger dissipated so much that all I needed to do to spend the remainder of it was to turn the radio off, which I did. Then I lay back down and stared at the ceiling, listening to the traffic out on Metropolitan Avenue. But then yesterday, I made my second try to join the sprawling, neverending facsimile of a conversation. I turned on the radio to hear the announcement of the new inductees into the Hall of Fame, and after pumping my fist for Jim Rice and whooping a little, I kept the radio on for the rest of the afternoon, tuned to the XM all-baseball station, attempting to bask in the moment as long as possible. Ironically, I first started thinking about calling into the afternoon show (hosted by Rob Dibble and the very same Jody MacDonald from years earlier) when I found myself disagreeing with the hosts’ comparison of Jim Rice to Reggie Jackson. When I was a kid, I hated Reggie Jackson as much as I loved Jim Rice, but when either Dibble or MacDonald (I forget which one, but they were in agreement on the subject) pointed out as an argumentative trump card that Jim Rice’s career slugging average was ten points higher than Reggie Jackson’s, I sort of wanted to punch the wall. How can you make your living talking about baseball and not be compelled to add when offering this stat that Rice benefited from playing in a great hitter’s park while Reggie toiled for years in Oakland, one of the worst hitter’s parks in the league? But I didn’t seriously consider calling in on that subject, because the last thing I wanted to do on a happy day for a childhood hero was to start using him as ballast in an attack on the hosts. Besides, I’m a non-confrontational guy. But something about the way the two hosts were talking throughout the afternoon made me want to put in my two cents. Basically, they both had the familiar "I know a Hall of Famer when I see one" attitude coursing through all their comments. As you may know, this attitude always comes with a statement along the lines of "statistics are fine up to a point, but ‘basement-dwelling number crunchers’ [an actual phrase from today’s vintage offering from Dan Shaughnessy] go way too far." What the holders of this attitude are saying is that they will accept the stats that they understand, but when you start going beyond batting average and hits and RBI, you are the kind of guy who lies around all day staring at the ceiling, wondering if it’s too early in the day to masturbate. While they happen to be right about at least one of us, I still find myself upset by their arrogance and ignorance. They are like guys with a magnifying glass deriding the arrival on the scene of a guy with a microscope. Instead of being curious about the microscope, they mock the duct tape on the microscope-weilder's glasses and give him a swirly. Or worse, they use their platform (a column, a radio show) to reduce the microscope-wielder to insignificance, to the size of an ant, and then of course they try to use their outdated tool to melt the ant. (For a less feverishly metaphor-driven rant about this general subject, see King Kaufman’s recent column.) But since I am not a confrontational guy, I wanted to shoehorn some apparently unconventional thinking into the conversation in a positive manner, so I decided for my call-in subject I would pick the guy in yesterday’s vote who I thought was most criminally underrepresented in the voting and make a case for him. I consulted baseball-reference.com, wrote down some numbers that though verging on a microscope were still firmly in the realm of a magnifying glass, and I made the call. Unlike years earlier, I actually got through to a producer, who asked me my name and where I lived, then asked me why I was calling. This turned out to be as far as I ever got. But for a while there, I thought I was going to have my say. I had numbers that showed my guy as the equal to recent "no-brainer" inductee Tony Gwynn, and as substantially superior to the guy, shown at the top of this post, who prior to yesterday’s induction of Rickey Henderson was generally thought to be the standard bearer for leadoff men in the Hall of Fame. Oh, what a case I was going to make! But after fielding calls for a while the hosts then turned to a long interview with a sportswriter, and I gave up and went back to my life in the basement (note: I actually live on the second floor). However, I imagine that even though I didn’t get through, I was still for a brief time a small part of the show, a possibility, a someone, a glowing line on the hosts’ computer screen: Josh from Chicago. Wants to talk about Tim Raines. *** (Love versus Hate update: Lou Brock's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Jim Rice in . . . The Nagging Question

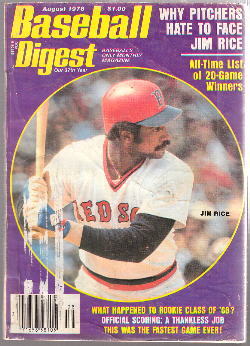

2009-01-11 13:29

Facts all come with points of view How do you best assess your memories, your subjective impressions? How do you transform the wisps and traces of what was into the plaque-solid affirmation of what is? I guess this is what is at issue with Jim Rice, and why there has been so much argument about him that writers broaching the well-worn subject of his candidacy for the Hall of Fame have started to preface their thoughts on the subject with an apology, like someone sheepishly playing a song on the jukebox that everyone else has grown tired of. The most passionately invested participants in the argument are those who use thoughtful statistical analysis to make the wisps and traces of Jim Rice seem like the aftermath of a trash fire. Recently, Sean Smith in Hardball Times damningly compared Jim Rice's Hall of Fame credentials to those of Brian Downing. Last year, Jay Jaffe at Baseball Prospectus concluded his analysis of Rice by saying "He’s no Hall of Famer, not by any stretch of the imagination." These stances are not at all lone voices in the wilderness, either, but part of a chorus that includes some of the best baseball writers in the country (Joe Posnanski and Rob Neyer come to mind) and that stretches back to the Big Kahuna himself, Bill James, who in his Historical Baseball Abstract called Jim Rice "probably the most overrated player of the last thirty years" and ranked him as the 27th best left-fielder of all-time, two places behind Rice's decent, profoundly unspectacular contemporary, Roy White. I want to believe that claims like that are not true. I want to believe that the wisps and traces of the past are the last visible glimpses of something golden. I want to believe there was something about Jim Rice, and it wasn't all just a figment of my imagination. I don't know if I'll ever have that belief confirmed, but I can say that Jim Rice sure seemed like a future Hall of Famer in 1978. In July of 1978 he appeared on the cover of Sport Magazine, along with a quote from Hank Aaron, who raved, "This kid’s gonna break the home-run record." The following month he made his debut, shown at the top of this page, as the subject of a Baseball Digest cover. "Pitchers hate to face Jim Rice," the cover caption claims. It’s quite a claim, if you think about it. I was never charged with the responsibility of trying to get Jim Rice out, but I certainly know what it’s like to hate to face something. You lie awake at night dreading it. Your stomach hurts. You whimper, verging on tears. You wonder how it would be if you just took off out west on a Greyhound and assumed a new identity. The clock becomes your enemy because it keeps dragging you closer to the thing you hate to face. Death, public speaking, a bully. According to the August 1978 Baseball Digest, Jim Rice was all these things to the ulcerated, nerve-wracked pitchers of the American League. The following April, Baseball Digest revealed that Rice had been named the American League’s "Most Dangerous Hitter" by a poll of players, executives, and writers. That same month, he graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. The magazine’s feature story on Rice focused primarily on his prickly relationship with writers, but it also set the mold for the feared descriptive that these days so nauseatingly often comes up in arguments about his candidacy for the Hall of Fame, your support or lack thereof for Rice revealed by whether or not you enclose the adjective in caustic air quotes: "He is among the most fearless as well as feared hitters in the game," Ron Fimrite wrote in 1979 without any trace of a detractor’s wheedling sarcasm or a supporter’s bullying bombast, "because he will stand his ground against the fiercest brushback artist. For that matter, he may be at his most dangerous after being hit or threatened by a pitch. And, as his four-year major league batting average of .306 attests, he is not exclusively a power hitter." The striking language of extreme, even violent, emotions used to describe Rice—hate, fear, danger—helped imbue the man with a mythic aura. Events that had no bearing on the winning or losing of games—Jim Rice was so strong he snapped a bat by merely check-swinging; in his free time, Jim Rice drove golf balls into orbit; Jim Rice was scary to talk to in the locker room, burning twin holes in your forehead with his glare; Jim Rice leaped into the stands to rescue a boy who had been drilled by a foul ball—fed into this aura of strength and ferocity and danger and heroism. To his credit, his aura seems to exist not only in the eyes of fans and sportswriters but in the eyes of his peers as well. Goose Gossage, perhaps Rice’s closest counterpart among pitchers during those years in terms of being thought of as an intimidator and not merely a skillful performer, had this to say to the Boston Globe about Rice just last year, upon his induction into the Hall of Fame: "If Jimmy played in this era, his numbers would be through the roof. The reason I say it’s easier to hit is because the hitter is protected so much. A pitcher can’t scare a hitter anymore or he’ll get thrown out of the game. The strike zone is the size of a postage stamp. Hitters are wearing all that armor, the ball is livelier, the ballparks are smaller. There weren’t many hitters that I feared when I came into the game, but when Jimmy stepped to the plate, he was as close as I came to being scared." I'll start: Rickey Henderson, Tim Raines, Alan Trammel, Bert Blyleven, Lee Smith, and, yes, Jim Rice Here's some music to ponder your choices by...Lee May

2009-01-09 05:26

According to the back of this card, Lee May drove in 195 runs for the Houston Astros in 1973, more RBI than anyone has ever produced in a single major league season. More than Lou Gehrig, Hack Wilson, Hank Greenberg, etc. Name a slugger, any slugger. Lee May topped him, according to the back of this card. But it’s a mistake, right? If it’s not, I can’t think of a more subtly shattering blow to my sanity than the sudden knowledge that for all these years, my whole conscious life, the subject I know most about includes a glaring absence of knowledge about the all-time single-season RBI champ. It would be like a guy who spent every spare hour birdwatching and reading about birds and studying birdcalls suddenly finding out that there was a bird known as the bald eagle. "Good lord, what is that?" he’d remark to his fellow birders as he stared through binoculars at the familiar patriotic icon perched on a high branch. By the time he lowered his binoculars to investigate the silence greeting his exclamation, his fellow birders would have realized he wasn’t joking, but shaky grins would remain frozen on all their faces. No one would be making any eye contact. But that’s too unfathomable to think about. I’d rather identify the 195 RBI as a typo. I’d rather envision some Topps temp concentrating on her glazed donut while thudding the 9 key instead of the 0 key on a typewriter, then later in the process the proofreader rationalizing his half-assed half-asleep effort by telling himself that he wouldn’t even care that much if he got canned. Thus, with these two parenting mediocrities—the key-entry functionary and the quality assurance functionary—a mistake is born. I should know. I work as a proofreader, which means all day long I search for mistakes. Sometimes my mind wanders and mistakes slip through. I think about this phenomenon a lot. It’s my window into one of the rare certainties about human life: mistakes will be made. Sometimes the mistakes won’t matter much, but other times they might. Someone’s mind wanders when they’re inspecting an airplane. Someone’s mind wanders when they’re checking a chest x-ray. Someone’s mind wanders when they’re speeding down the highway. Last night my wife told me about what she saw on her long drive home. One of the cars in a crash had been crushed to the size of a juke box. Years ago, on a road trip, we’d been on that same highway and had seen the aftermath of a crash involving eight or nine cars all crumpled and intertwined in an awful metallic conga line, complete with sirens and revolving red lights. One mistake had been made. One little mistake. It’s the kind of thing that can make you want to never leave your house, or to pack yourself in a thick coating of bubble wrap for so much as a short walk to the corner to buy Q-Tips. So for the sake of my continuing ability to barely function in society, maybe what I need to do is once again entertain the idea that the info on the back of Lee May’s card isn’t a mistake. Maybe every other source on the subject is wrong, and this one card is right. Maybe Lee May just had one magical season where he could do no wrong. I never had such a season (and judging by Lee May’s expression on the front of the card, I think it’s safe to assume that he never had such a season, either), but I did at least have one long summer afternoon. I was nine or ten and I went to stay overnight at my friend Mike’s house. Mike lived in town, while I lived far out in the country, where there weren’t very many other kids around, so it was amazing to me when Mike and I took a few steps out of his house and found a bunch of kids already gathering in a big open grassy lot that happened to be next a cemetary. Teams were formed, a baseball diamond laid out using rocks and pieces of clothing for bases. For some reason we used a tennis ball instead of a baseball. It was a good choice. Everyone was a slugger, thocking the fuzzy yellow ball into the far reaches of the field, the farthest clouts bounding all the way into the newest rows of graves. By this time I had fallen in love with the statistics on the backs of baseball cards, so as the slugfest went on and the runners kept whirling around the bases and home I started getting giddy about my own stats for the game. Let’s see. Four doubles, a couple triples, three home runs, fourteen RBIs. Or is it fifteen? I was, I decided, an RBI machine. I don’t remember how outs were even made, but somehow they were once every half-dozen runs, because the beautiful thing was that everyone on both teams got easy chance after easy chance to be a record-breaking slugger. I guess if I had the opportunity to play that kind of a game every day I might have grown bored with it, but since I so rarely got to play with a huge group of other kids I loved it. As I remember it, the game didn’t end with anyone losing but with the slow soft arrival of dusk, the beaten tennis ball a dimming yellow glow floating toward the batter then flaring in a sizzling shooting star arc deep into the outfield. Finally someone drove the ball into the granite stubs and slabs at the far border of the field and it was too dark to find it, though we all looked for a while, every player on both teams, everyone a cheerful chattering superstar slaloming fearlessly through the graves. Death of a Stooge (Ron Asheton, 1948-2009)

2009-01-07 06:13

In the early 1970s in Los Angeles, when his doomed, addiction-addled band was lurching the last tortured miles of its perversely majestic self-destruction, Ron Asheton met Chris Lamont, granddaughter of Larry Fine. Lamont introduced Stooge to Stooge at Fine’s cramped room in the Motion Picture Rest Home. Asheton told the story in the great oral history Please Kill Me, which I perused for Ron Asheton passages last night over a couple stiff drinks after hearing that Asheton was just found dead at his home in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He had had a few strokes, and when I first met him, I could hardly understand a thing he said, but I wanted to keep going back, and Chris didn’t want to go back as much as me, so I finally called him up and said, "Hey, Larry, can I come by?" That passage was the first in Please Kill Me that I revisited last night, because I’ve always found it funny and touching, especially considering that while Ron Asheton was pulling Larry Fine back into the land of the living his bandmates were gazing with stony apathy at their drug-addled leader Iggy as he dabbled in his mostly involuntary hobby of nodding off face down in a swimming pool. As I worked my way backwards through the Ron Asheton passages in the book, I noticed that Asheton had a habit of positioning himself at the edge of chaotic situations, and of pulling something valuable and alive from the chaos. I’d been to New York with Iggy a few times before we went to record the first album. The first time we went, before we got signed to Elektra, was when Iggy took STP for the first time. He didn’t know it was a three-day trip, so guess who got to watch him? Me. Iggy has always gotten a lot of the credit for the Stooges, as he should, but as the above passage suggests, without Ron Asheton Iggy might have been just another unleashed madman wandering aimlessly through the night with pupils the size of nickels. In the passage below, describing a moment from before the Stooges ever existed, when Asheton and future Stooges bassist Dave Alexander took a trip to to England, reveals that Asheton may have been the first Stooge to get a vision of the uncharted territory the band would one day explore. We went to see the Who at the Cavern. It was wall to fucking wall of people. We muscled through to about ten feet from the stage, and Townshend started smashing his twelve-string Rickenbacker. You're lucky if you hear the life you're supposed to be leading calling to you, even luckier if you've got the courage to follow that call. Ron Asheton heard and followed all the way until the end, as evidenced by this recent clip of the reunited Stooges. Asheton's the guy using a guitar to light a fire... Rick Manning

2009-01-05 07:06

We all live for a while in the land of might. We might go anywhere. We might become anything. When do you realize you’ve been cast out of this land? When does your what if congeal into what is? That moment seems to be happening in this 1979 card, as a melancholy Rick Manning in extreme close-up seems unable to look straight at the viewer, as if in fear that the viewer will start grilling him about why he hasn’t become the next Tris Speaker, or at the very least a less hilarious version of Mickey Rivers. A few years earlier, in his rookie season of 1975, Rick Manning hit .285, which along with his spectacular fielding in centerfield would have earned him the rookie of the year award in most seasons. Unfortunately, he made his debut the same season as 1975 MVP Fred Lynn (not to mention Lynn’s teammate Jim Rice). The following season, Manning won a Gold Glove, upped his average to .292, and doubled his home run output from 3 to 6. Visions of even better seasons, spangled with a .300 average, 40-50 steals, and double-digit home runs, seemed not only possible but likely. "He’s the most exciting ballplayer the Indians have had in many years," his manager Frank Robinson said in 1976, in the June issue of Baseball Digest. "I think his potential is unlimited." Manning stumbled in 1977, hitting just .227. At the end of that season the Indians traded away his teammate Dennis Eckersley, apparently fearing clubhouse dissension over the fact that Manning had been having an affair with Eckersley's wife. It stands to reason that before the trade the Indians evaluated both players on what lay ahead for them, and decided that despite his disappointing 1977 campaign 22-year-old Rick Manning still owned more acreage than 22-year-old Dennis Eckersley in the land of might. In 1978, while Eckersley was winning 20 games for his new team, the Red Sox, Rick Manning edged his average back up to .263, but in 1979, the year this card came out, he slid back a little, to .259, which turned out to be the most accurate portrait of his talents he’d ever produce in a single season, considering the .257 lifetime average he ultimately finished with after 13 quiet seasons at or near the basement of the American League East. As Rick Manning's career was drawing to a close, Dennis Eckersley also seemed to be just about through playing professional baseball. In 1987, Manning’s final season, Eckersley was traded with someone named Dan Rohn to the A’s for three minor leaguers. It wasn't the kind of deal that had any might in it. Just bodies replacing other bodies. But as most baseball fans know, in Oakland Eckersley was moved to the bullpen, and he proceeded to have a promising season, his first in years. The A's must have thought, correctly as it turned out, "Hey, we just might have something here." This is the haunting thing about the land of might. Even after we've been cast out we're never sure when to stop hoping we might be able to return. *** (These thoughts on Rick Manning began when I noticed him on the cover of the aforementioned June 1976 Baseball Digest while perusing the complete Baseball Digest archives. Thanks to John Rosenfelder at earbender for giving me a heads-up about this amazing new online baseball time machine.) |