|

Monthly archives: September 2006

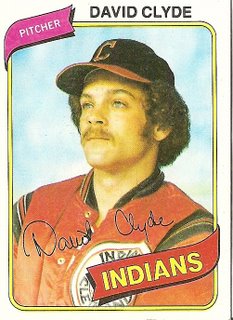

David Clyde

2006-09-30 10:36

In

this 1980 card, David Clyde's last, the former nationwide high school

sensation displays his league-leading thousand-yard stare in front of

what appears to be a painted backdrop. Maybe the fake blue sky was

wheeled in to cover the mildewed bricks of the windowless room, deep

within the Indians' spring training barracks, where the oft-disabled

former number 1 draft pick preferred to endure his daylight hours.

Maybe Topps purchased the backdrop at the going-out-of-business sale of

a photographer who, until the word statutory started getting flung

around, made his living creating portraits of high school seniors. Or

maybe the picture was actually taken by said photographer, who had

moved to Florida with a U-Haul full of backdrops to try to start anew

and had picked up freelance work involving the subjects the pensioned

Topps photographers preferred to avoid. Maybe after "the shoot" the

photographer and David Clyde went for beers at the topless joint out by

the abandoned A&W and neither one asked any questions about the

past. In

this 1980 card, David Clyde's last, the former nationwide high school

sensation displays his league-leading thousand-yard stare in front of

what appears to be a painted backdrop. Maybe the fake blue sky was

wheeled in to cover the mildewed bricks of the windowless room, deep

within the Indians' spring training barracks, where the oft-disabled

former number 1 draft pick preferred to endure his daylight hours.

Maybe Topps purchased the backdrop at the going-out-of-business sale of

a photographer who, until the word statutory started getting flung

around, made his living creating portraits of high school seniors. Or

maybe the picture was actually taken by said photographer, who had

moved to Florida with a U-Haul full of backdrops to try to start anew

and had picked up freelance work involving the subjects the pensioned

Topps photographers preferred to avoid. Maybe after "the shoot" the

photographer and David Clyde went for beers at the topless joint out by

the abandoned A&W and neither one asked any questions about the

past.

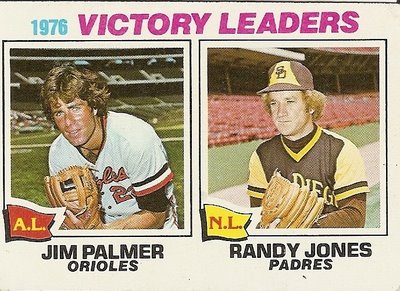

1976 Victory Leaders

2006-09-29 06:25

On

July 28, 1976, Randy Jones went 10 innings in a 2-1 victory to push his

dazzling record to 18 wins and 4 losses. After a rocky start to his

career that included an 8 and 22 season, Jones had broken through in

1975 with 20 wins, and in 1976 he looked to be on his way to a whole

new level of stardom, Sports Illustrated even featuring him

on their cover, wondering if he could become the first National Leaguer

since Dizzy Dean to reach the astonishing level of 30 wins. There was,

in other words, a brief moment in time when Randy

Jones--junk-ball-tossing Randy Jones, pale-skinned bozo-haired Randy

Jones, thin-lipped dough-faced Randy Jones, Randy Jones in his Padre

fast-food uniform, surrounded by feckless Padre teammates and empty

seats and the blissfully indifferent blue of a San Diego sky--had

something over Jim Palmer. In the latter stages of 1976, of course, the

magic dissipated. Jones didn't get close to 30 wins for the year and

never finished another season after 1976 with more wins than losses.

Meanwhile, Jim Palmer, shown here without headgear for no other

apparent reason than to show off that his flowing blow-dried hair is

spectacularly superior to Jones's cap-crushed rusted Brillo, continued

tanly vying for Cy Young awards, breezing into the playoffs, and posing

for lucrative underwear ads. When I look at this card I find myself

wishing what Randy Jones seems to be wishing--that he could somehow

cross over from his photo to the golden realm of the A.L. Victory

Leader so as to kick Jim Palmer in his Jockey-Shorted nuts. On

July 28, 1976, Randy Jones went 10 innings in a 2-1 victory to push his

dazzling record to 18 wins and 4 losses. After a rocky start to his

career that included an 8 and 22 season, Jones had broken through in

1975 with 20 wins, and in 1976 he looked to be on his way to a whole

new level of stardom, Sports Illustrated even featuring him

on their cover, wondering if he could become the first National Leaguer

since Dizzy Dean to reach the astonishing level of 30 wins. There was,

in other words, a brief moment in time when Randy

Jones--junk-ball-tossing Randy Jones, pale-skinned bozo-haired Randy

Jones, thin-lipped dough-faced Randy Jones, Randy Jones in his Padre

fast-food uniform, surrounded by feckless Padre teammates and empty

seats and the blissfully indifferent blue of a San Diego sky--had

something over Jim Palmer. In the latter stages of 1976, of course, the

magic dissipated. Jones didn't get close to 30 wins for the year and

never finished another season after 1976 with more wins than losses.

Meanwhile, Jim Palmer, shown here without headgear for no other

apparent reason than to show off that his flowing blow-dried hair is

spectacularly superior to Jones's cap-crushed rusted Brillo, continued

tanly vying for Cy Young awards, breezing into the playoffs, and posing

for lucrative underwear ads. When I look at this card I find myself

wishing what Randy Jones seems to be wishing--that he could somehow

cross over from his photo to the golden realm of the A.L. Victory

Leader so as to kick Jim Palmer in his Jockey-Shorted nuts.

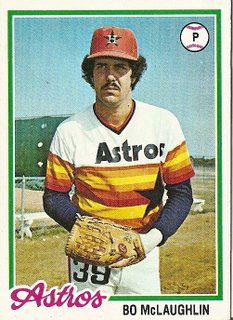

Bo McLaughlin

2006-09-28 06:38

In

the 1970s, everyone was in one way or another a stranger in a strange

land. The clear cultural battle lines of the shrill, combative '60s had

blurred. Everyone had sideburns and a mustache. Everyone was aging.

Everyone worked a regular job and dabbled in jogging and cocaine.

Everyone bought their children faulty mood rings and overly cheerful

sex education handbooks. Everyone filed for divorce. Everyone wore

rainbow colors and succumbed to depression. Everyone was Bo McLaughlin. In

the 1970s, everyone was in one way or another a stranger in a strange

land. The clear cultural battle lines of the shrill, combative '60s had

blurred. Everyone had sideburns and a mustache. Everyone was aging.

Everyone worked a regular job and dabbled in jogging and cocaine.

Everyone bought their children faulty mood rings and overly cheerful

sex education handbooks. Everyone filed for divorce. Everyone wore

rainbow colors and succumbed to depression. Everyone was Bo McLaughlin.

Rudy Meoli

2006-09-27 06:24

When

I was a kid this card was my favorite of the few that featured action

shots. The moment seemed spectacular, kinetic, dramatic, Meoli

proclaiming with the spread of his arms "behold," his head thrown back

in awe. It was years before I realized that all I was looking at was

some guy who'd just hit an infield popup. Even to this day there's some

residual effect of my inability to interpret the blatantly obvious in

this picture: I still on some level think of Rudy Meoli, a backup

infielder with a .212 lifetime average and more career errors than

extra-base hits, as one of the most thrilling performers of his era. When

I was a kid this card was my favorite of the few that featured action

shots. The moment seemed spectacular, kinetic, dramatic, Meoli

proclaiming with the spread of his arms "behold," his head thrown back

in awe. It was years before I realized that all I was looking at was

some guy who'd just hit an infield popup. Even to this day there's some

residual effect of my inability to interpret the blatantly obvious in

this picture: I still on some level think of Rudy Meoli, a backup

infielder with a .212 lifetime average and more career errors than

extra-base hits, as one of the most thrilling performers of his era.

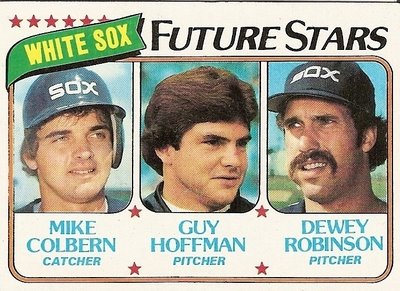

White Sox Future Stars

2006-09-26 07:05

As

everyone with even the most glancing familiarity with baseball knows,

the three figures pictured on this remarkably prescient Topps card from

1980 went on to form one of the most renowned trio of players in major

league history, Mike Colbern, Guy Hoffman, and Dewey Robinson spoken of

by all in hushed, reverent tones for the way they repeatedly led the

previously long-suffering Chicago White Sox franchise to championship

after championship, and for the way they brought glamour and excitement

to the world of baseball by their various relationships, amorous and

otherwise, with Hollywood starlets and heads of state, and for how they

changed the way the game was played, the electric Mike Colbern striking

first by, in his rookie season, breaking the single-season record for

doubles and triples while also shattering the mark for stolen bases by

a catcher; the debonair Guy Hoffmann baffling batters with not one but

two patented pitches never mastered by another hurler--the Yancey Street

Stinker and the Hummingbird Conniption; the charismatic Dewey Robinson

closing wins with ferocious alacrity and then celebrating with the

mound-launched Dewey Twirl, a physical spasm of such grace and joy

and--even after the last of his 447 lifetime saves--such a feeling of

spontaneity that it is no wonder it inspired a hit song so contagious

and ubiquitous that an all-star lineup featuring Toni Basil, Ron Wood,

Billy Ocean, Laura Branigan, and Oates performed a version of it to

close Live Aid, global starvation defeated by sheer infectious

synth-beated happiness. That performance foreshadowed a shift in the

careers of the Big Three, as they will forever be known, from mere

baseball superstars to world changers, that latter role reaching its

first but very likely not last of its history-book-worthy climaxes when

Colbern, Hoffman, and Robinson (the names always mentioned in that

order even before poet laureate Robert Pinsky solidified the litany

while bringing his dying art back from the ivory tower hinterlands to

the spotlit realm of Bruce Springsteen, The Cosby Show, and

Mr. T with his best-selling ode to the famous three, "Chicago Stars

Incandescent in the Gloom") made a visit to the Berlin Wall in 1989 and

with humor, diplomacy, and all-American chisel-jawed resolve crisply

recorded the final three outs of the Cold War. I was tempted to sell

this card, by far the most valuable of my collection, around then.

After spending some years at an obscure state college adrift in the

static of subpar hallucinogens, I was about to receive a diploma with a

major in creative writing, my prospects for employment as narrow as if

I'd majored in saying what animal shapes I thought I saw in the clouds.

But I decided the legendary threesome was not done gathering glory, so

I held onto my one and only asset, figuring it could only grow in

value, and embarked on a life of thrilling menial labor often

punctuated by periods of spirit-emboldening unemployment. All you need

to do is pick up a newspaper and see the ever-widening transcontinental

influence of Mike Colbern, CEO of Intel Computers, Guy Hoffmann, Nobel

Peace Prize-winning solver of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and

President Dewey "FDR on 'Roids" Robinson to see that in this as in all

of my major life decisions I have, as Topps did with this card,

forecasted the future with pragmatic and sober-minded brilliance. As

everyone with even the most glancing familiarity with baseball knows,

the three figures pictured on this remarkably prescient Topps card from

1980 went on to form one of the most renowned trio of players in major

league history, Mike Colbern, Guy Hoffman, and Dewey Robinson spoken of

by all in hushed, reverent tones for the way they repeatedly led the

previously long-suffering Chicago White Sox franchise to championship

after championship, and for the way they brought glamour and excitement

to the world of baseball by their various relationships, amorous and

otherwise, with Hollywood starlets and heads of state, and for how they

changed the way the game was played, the electric Mike Colbern striking

first by, in his rookie season, breaking the single-season record for

doubles and triples while also shattering the mark for stolen bases by

a catcher; the debonair Guy Hoffmann baffling batters with not one but

two patented pitches never mastered by another hurler--the Yancey Street

Stinker and the Hummingbird Conniption; the charismatic Dewey Robinson

closing wins with ferocious alacrity and then celebrating with the

mound-launched Dewey Twirl, a physical spasm of such grace and joy

and--even after the last of his 447 lifetime saves--such a feeling of

spontaneity that it is no wonder it inspired a hit song so contagious

and ubiquitous that an all-star lineup featuring Toni Basil, Ron Wood,

Billy Ocean, Laura Branigan, and Oates performed a version of it to

close Live Aid, global starvation defeated by sheer infectious

synth-beated happiness. That performance foreshadowed a shift in the

careers of the Big Three, as they will forever be known, from mere

baseball superstars to world changers, that latter role reaching its

first but very likely not last of its history-book-worthy climaxes when

Colbern, Hoffman, and Robinson (the names always mentioned in that

order even before poet laureate Robert Pinsky solidified the litany

while bringing his dying art back from the ivory tower hinterlands to

the spotlit realm of Bruce Springsteen, The Cosby Show, and

Mr. T with his best-selling ode to the famous three, "Chicago Stars

Incandescent in the Gloom") made a visit to the Berlin Wall in 1989 and

with humor, diplomacy, and all-American chisel-jawed resolve crisply

recorded the final three outs of the Cold War. I was tempted to sell

this card, by far the most valuable of my collection, around then.

After spending some years at an obscure state college adrift in the

static of subpar hallucinogens, I was about to receive a diploma with a

major in creative writing, my prospects for employment as narrow as if

I'd majored in saying what animal shapes I thought I saw in the clouds.

But I decided the legendary threesome was not done gathering glory, so

I held onto my one and only asset, figuring it could only grow in

value, and embarked on a life of thrilling menial labor often

punctuated by periods of spirit-emboldening unemployment. All you need

to do is pick up a newspaper and see the ever-widening transcontinental

influence of Mike Colbern, CEO of Intel Computers, Guy Hoffmann, Nobel

Peace Prize-winning solver of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and

President Dewey "FDR on 'Roids" Robinson to see that in this as in all

of my major life decisions I have, as Topps did with this card,

forecasted the future with pragmatic and sober-minded brilliance.

Bill Buckner

2006-09-25 06:22

"There's

just this for consolation: an hour here or there where our lives seem,

against all odds and expectations, to burst open and give us everything

we've ever imagined, though everyone but children (and perhaps even

they) knows these hours will inevitably be followed by others, far

darker and more difficult." "There's

just this for consolation: an hour here or there where our lives seem,

against all odds and expectations, to burst open and give us everything

we've ever imagined, though everyone but children (and perhaps even

they) knows these hours will inevitably be followed by others, far

darker and more difficult."-- Michael Cunningham, The Hours

Permalink |

No comments.

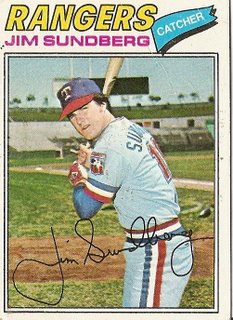

Jim Sundberg

2006-09-24 07:29

I

love sleeping. I also enjoy, in descending order, napping, resting,

lying around, sitting there, staring off into the middle distance,

leaning on girders, slouching, standing, and aimlessly walking. It's

possible that my slack physical--or is it moral?--makeup is one of the

reasons I have spent such an inordinate amount of my life contemplating

baseball. With one notable exception, baseball affords its players

significant spans of empty time, outfielders often free to wonder about

their disintegrating marriages or what kind of cheese to get on their

next cheeseburger, infielders in their more anxious moments between

pitches at liberty to polish the tics of their various

obsessive-compulsive disorders, relief pitchers able to loaf and laze

for most of the game like natives of an imaginary island paradise that

smells of tobacco juice and Tiger Balm, starting pitchers buoyed on

their occasional work days by the knowledge that they can, if they so

choose, spend the following few days reorganizing their record

collection or gambling at the dog track or, like the long-successful

southpaw Mickey Lolich, becoming morbidly obese without any of these

lifestyle choice necessarily having a negative impact on their

abilities. And designated hitters, of course, can pass all but a tiny

fraction of each game in the clubhouse eating Pringles and watching

pornography. Only the catcher, wrapped in heavy pads and armor,

involved in every play and busy between plays with the planning of the

next play, is barred from taking pause. He is like a drummer in a

go-nowhere acid rock band, chained to the beat while his cohorts

explore all manner of irrelevancies, or like that one thin pale guy at

the hippie commune who washes all the dishes and mails in the

zoning-fee checks while everyone else has chant-filled orgies and

wanders through the forest to carry on tearful conversations with moss. I

love sleeping. I also enjoy, in descending order, napping, resting,

lying around, sitting there, staring off into the middle distance,

leaning on girders, slouching, standing, and aimlessly walking. It's

possible that my slack physical--or is it moral?--makeup is one of the

reasons I have spent such an inordinate amount of my life contemplating

baseball. With one notable exception, baseball affords its players

significant spans of empty time, outfielders often free to wonder about

their disintegrating marriages or what kind of cheese to get on their

next cheeseburger, infielders in their more anxious moments between

pitches at liberty to polish the tics of their various

obsessive-compulsive disorders, relief pitchers able to loaf and laze

for most of the game like natives of an imaginary island paradise that

smells of tobacco juice and Tiger Balm, starting pitchers buoyed on

their occasional work days by the knowledge that they can, if they so

choose, spend the following few days reorganizing their record

collection or gambling at the dog track or, like the long-successful

southpaw Mickey Lolich, becoming morbidly obese without any of these

lifestyle choice necessarily having a negative impact on their

abilities. And designated hitters, of course, can pass all but a tiny

fraction of each game in the clubhouse eating Pringles and watching

pornography. Only the catcher, wrapped in heavy pads and armor,

involved in every play and busy between plays with the planning of the

next play, is barred from taking pause. He is like a drummer in a

go-nowhere acid rock band, chained to the beat while his cohorts

explore all manner of irrelevancies, or like that one thin pale guy at

the hippie commune who washes all the dishes and mails in the

zoning-fee checks while everyone else has chant-filled orgies and

wanders through the forest to carry on tearful conversations with moss.Jim Sundberg, winner of seven consecutive Gold Glove awards, caught 90% or more of his team's games in more seasons (six) than any man in history. In each of these seasons his team played 81 home games in the blast-furnace heat of an undomed stadium in Arlington, Texas. In two of those seasons, 1977 and 1978, he even finished 15th in the MVP voting, despite the fact that he was only slightly more imposing at bat than cartoon-oriole-haunted Rich Dauer. His worth was based almost completely on the fact that he adhered so fully and competently to that most coachly of all exhortations--"keep your head in the game"--(a demand which, because of my consistent failure to follow it, still grates on my ears all these many years after it was repeatedly shouted in my direction) that he was able to prop up his entire team like Atlas supporting the world. His Texas Ranger squads were known to stake early claims on first place only to wilt as the heat continued to pound down throughout the summer. But while the Bump Willses and Jim Umbargers of the world faltered, Jim Sundberg continued to perform his demanding job effectively day in and day out, an Atlas who remained in his world-supporting squat even as his precious burden crumbled to pebbles. With all this in mind, I can't help thinking that in this card Jim Sundberg's penetrating squint, which seems to be directed straight at me, betrays a keen premonition on his part that I too will disappoint him, that I haven't got what it takes, that I am, just as I have often suspected, a fairly tall but mostly worthless pile of shit. Larry Wolfe

2006-09-23 07:48

In

1978 the Red Sox' young and formerly promising third baseman, Butch

Hobson, began maiming fans with his attempts to throw out runners at

first base. The Red Sox stuck with him in 1979, but not before

installing a backup plan along the lines of buying a moped at a tag

sale in case the fraying brakes on the El Camino went out completely.

According to the two-item star-bulleted list below the tepid,

diminishing statistics on the back of this baseball card, the tag sale

moped, Larry Wolfe, had just three short years earlier absolutely

terrorized the Southern League by leading it in Sacrifice Flies.

Incredibly, just two years before that, this same Larry Wolfe had

topped all Midwest League third basemen in Double Plays. (The card does

not specify if he participated in the Double Plays as a fielder or a

hitter, however.) Other information to be gleaned about Larry Wolfe

from the back of this card includes that he was acquired via trade

(though it does not say that the trade was for Dave Coleman, two years

removed from getting no hits in 12 at-bats in the only major league

experience he would ever have), he's my birthday neighbor (his special

moment one thin day from my own), and he was born in the

legitimate-sounding Melbourne, Florida, but now supposedly lived in a

place in California called "Rancho Cordova." In

1978 the Red Sox' young and formerly promising third baseman, Butch

Hobson, began maiming fans with his attempts to throw out runners at

first base. The Red Sox stuck with him in 1979, but not before

installing a backup plan along the lines of buying a moped at a tag

sale in case the fraying brakes on the El Camino went out completely.

According to the two-item star-bulleted list below the tepid,

diminishing statistics on the back of this baseball card, the tag sale

moped, Larry Wolfe, had just three short years earlier absolutely

terrorized the Southern League by leading it in Sacrifice Flies.

Incredibly, just two years before that, this same Larry Wolfe had

topped all Midwest League third basemen in Double Plays. (The card does

not specify if he participated in the Double Plays as a fielder or a

hitter, however.) Other information to be gleaned about Larry Wolfe

from the back of this card includes that he was acquired via trade

(though it does not say that the trade was for Dave Coleman, two years

removed from getting no hits in 12 at-bats in the only major league

experience he would ever have), he's my birthday neighbor (his special

moment one thin day from my own), and he was born in the

legitimate-sounding Melbourne, Florida, but now supposedly lived in a

place in California called "Rancho Cordova."Rancho Cordova? My only theories about this preposterous place-name are as follows: 1. Larry Wolfe was living in a van at the time the baseball card people surveyed him. As his profound chinlessness precluded him from enlivening his van-bound nights with female accompaniment, Larry Wolfe had ample time to absorb the lessons embedded in the babble from his portable television, lessons which perhaps reached their most concentrated distillate in the car advertisement phrase "fine Corinthian leather," a notion invented by ad executives to avoid using just the definable but syllabically-challenged word "leather." Fantasy Island's Ricardo Montalban spoke these words when describing a Buick, and perhaps the mellifluous, exotic lilt of the voice of Montalban, the man who every week taught the likes of Tom Bosley and Shelley Winters important lessons by spiking their deepest fantasy with setbacks that peaked at twenty and forty minutes past the hour, drifted deep into Larry Wolfe's being, and when he was asked where he lived by a Topps functionary perhaps Larry Wolfe responded in the emptily inventive voice of Tatoo's overlord, Larry Wolfe a man of his times, mimicking the invention of glamour to wallpaper grim reality. 2. Upon reaching the big leagues, a hopeful Larry Wolfe was immediately victimized by a Glengarry Glen Ross type of real estate scam. In this theory, there is a Rancho Cordova, but it is a desolate expanse of sand and scorpions. P.S. The brakes soon went out completely on the El Camino. The moped hit .244 in 1979 and .130 in 1980 and by 1981 was one way or another living year-round in Rancho Cordova. Fred Howard

2006-09-22 07:26

-- Bon Scott

July 12, 1979: The sky was raining flat black discs and lit M-80s. By the late innings, the visiting Detroit Tiger outfielders wore batting helmets in the outfield. A vendor reported selling 49 cases of beer that night, more than double the number he'd sold on any single night in his many years on the job. Smoldering bongs were passed from hand to hand up rows like change for a hot dog, giant glossy paper airplanes made of promotional posters featuring a sultry blond model known only as Lorelei swooped and dove amid the hail of explosives and frisbeed LPs and 45s, and inebriated throngs in the parking lot jumped up and down on cars and set fire to white-suited John Travolta dolls and searched for illegal entry into the slightly more focused mayhem inside the packed stadium. As game one of the scheduled doubleheader progressed this search gained urgency, for between games a local 24-year-old disc jockey and the aforementioned Lorelei were going to detonate a mountain of disco records. Almost immediately after this detonation occurred, a stream and then a gushing wave of longhaired attendees flowed onto the playing field. The desire to get onto the field was strong, as reported by an anonymous contributor to a Disco Demolition Night webpage on whiteseoxinteractive.com: Inside the home team's clubhouse, as his teammates went through the motions of preparing for a second game that they had begun to correctly assume would never be played, Fred Howard, shown here in the only baseball card ever produced in his likeness, tried to wash off whatever residue had accrued during his stint as the losing pitcher of game one. Though he probably didn't see it this way, he had done his part. As another contributor to the webpage cited above recalled: "The Sox lost the first game to Detroit, which just seemed to aggravate and energize the crowd." No one seems to remember Fred Howard, or even to ever have been aware of his existence, but the 1970s, that tale told by an idiot full of sound and fury signifying nothing, may not have had its decade-punctuating Woodstock without his heroic failure.

Rich Dauer

2006-09-21 05:40

As

can be seen from his troubled expression, Rich Dauer, the epitome of

the quiet, steady, reliable middle infielder, has surrendered himself,

albeit reluctantly, to a dialogue with the ever-cheerful and vaguely

racist cartoon representation of an Oriole on his cap. The

conversation, largely a monologue aimed at Dauer in the approximate

voice of Scatman Crothers, most likely began in 1976, when Dauer was

first summoned to the major leagues after blitzing the triple-A

Independent League with a .336 average. The hits stopped coming in the

majors, evidenced by a .103 average during the September call-up, and

Dauer, influenced by a lonely late night hotel room viewing of a

twilight-era Flintstones episode featuring the execrable Gazoo,

attempted to laugh in the face of the widening void by gazing at his

scarily bright and new big-league cap and briefly imagining that he too

had a little friend that only he could see. "Don't you worry none

there, boss," Rich Dauer mumbled, using his hands to make the beak of

the Oriole move. "You'll gets them tomorrow, plain as de sun gone rise

in de west." Unfortunately, when you start telling jokes to yourself,

it's over. Somewhere during the next season, his first full summer of

authoring soft popups and dribblers in the majors, Dauer, a former

number 1 draft choice, a former big star in high school, college, and

the minor leagues, relinquished the reigns on the voice. In this photo,

taken in the spring after that first full season, Dauer appears to be

on the brink of breaking under the weight of the Oriole's exhortations,

which are so unrelentingly cheery that they have begun to reveal within

them the bleak sharp seed of mockery. As

can be seen from his troubled expression, Rich Dauer, the epitome of

the quiet, steady, reliable middle infielder, has surrendered himself,

albeit reluctantly, to a dialogue with the ever-cheerful and vaguely

racist cartoon representation of an Oriole on his cap. The

conversation, largely a monologue aimed at Dauer in the approximate

voice of Scatman Crothers, most likely began in 1976, when Dauer was

first summoned to the major leagues after blitzing the triple-A

Independent League with a .336 average. The hits stopped coming in the

majors, evidenced by a .103 average during the September call-up, and

Dauer, influenced by a lonely late night hotel room viewing of a

twilight-era Flintstones episode featuring the execrable Gazoo,

attempted to laugh in the face of the widening void by gazing at his

scarily bright and new big-league cap and briefly imagining that he too

had a little friend that only he could see. "Don't you worry none

there, boss," Rich Dauer mumbled, using his hands to make the beak of

the Oriole move. "You'll gets them tomorrow, plain as de sun gone rise

in de west." Unfortunately, when you start telling jokes to yourself,

it's over. Somewhere during the next season, his first full summer of

authoring soft popups and dribblers in the majors, Dauer, a former

number 1 draft choice, a former big star in high school, college, and

the minor leagues, relinquished the reigns on the voice. In this photo,

taken in the spring after that first full season, Dauer appears to be

on the brink of breaking under the weight of the Oriole's exhortations,

which are so unrelentingly cheery that they have begun to reveal within

them the bleak sharp seed of mockery.

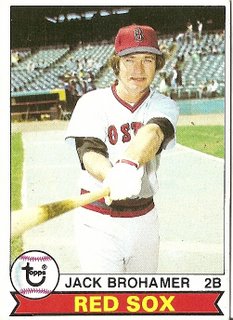

Jack Brohamer

2006-09-20 07:17

Jack

Brohamer seems like he may be about to cry. I can't decide if he's

losing a tug-of-war with an acned batboy or if he's just claimed

something along the lines of "I wouldn't touch that with a ten-foot

pole" and is now being forced to test that oath. If it's the latter, I

can't help but wonder what it is he may or may not touch with his

distancing tool. Has George Scott just taken a steaming dump near the

on-deck circle? Is manager Don Zimmer showing off the whole body tan he

got in the offseason at a nudist colony for people with metal plates in

their head? Or is this simply the way Jack Brohamer has come to feel

about life in general in the direct aftermath of the Red Sox' 1978

collapse for the ages? As I may someday be able to expound upon in more

detail in another of these letters to decomposing heaven ("gods too

decompose," proclaimed Ken Forsch's favorite philosopher), my seemingly

unstoppable Red Sox squandered a giant late-season lead to the Yankees,

recovered in time to force a one-game playoff, took a two-run lead in

the playoff game, lost the lead, then rallied but fell short trying to

regain the lead. For some reason Jack Brohamer started that playoff

game, a weak-hitting left-handed bench guy pitted against the Yankees'

left-handed super-ace, Ron Guidry, who was putting the finishing

touches on one of the four or five greatest seasons ever posted by a

starting pitcher. No wonder life seemed scary to Jack Brohamer. From

October 2, 1978, onward, there would always be a part of me that felt

the same way. Jack

Brohamer seems like he may be about to cry. I can't decide if he's

losing a tug-of-war with an acned batboy or if he's just claimed

something along the lines of "I wouldn't touch that with a ten-foot

pole" and is now being forced to test that oath. If it's the latter, I

can't help but wonder what it is he may or may not touch with his

distancing tool. Has George Scott just taken a steaming dump near the

on-deck circle? Is manager Don Zimmer showing off the whole body tan he

got in the offseason at a nudist colony for people with metal plates in

their head? Or is this simply the way Jack Brohamer has come to feel

about life in general in the direct aftermath of the Red Sox' 1978

collapse for the ages? As I may someday be able to expound upon in more

detail in another of these letters to decomposing heaven ("gods too

decompose," proclaimed Ken Forsch's favorite philosopher), my seemingly

unstoppable Red Sox squandered a giant late-season lead to the Yankees,

recovered in time to force a one-game playoff, took a two-run lead in

the playoff game, lost the lead, then rallied but fell short trying to

regain the lead. For some reason Jack Brohamer started that playoff

game, a weak-hitting left-handed bench guy pitted against the Yankees'

left-handed super-ace, Ron Guidry, who was putting the finishing

touches on one of the four or five greatest seasons ever posted by a

starting pitcher. No wonder life seemed scary to Jack Brohamer. From

October 2, 1978, onward, there would always be a part of me that felt

the same way.

Permalink |

No comments.

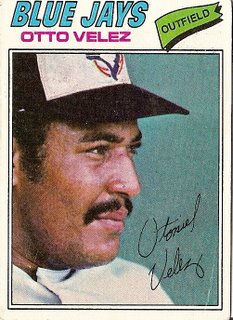

Otto Velez

2006-09-19 07:18

There

was something sturdy and elemental about Otto Velez. I have no memory

at all of him as a Yankee (apparently he made three plate appearances

in the 1976 World Series, striking out each time), but as soon as he

became a member of the first Blue Jay team he somehow seemed to have

always existed. All the other Blue Jays flickered half-formed like

figures on the malfunctioning pads of the Starship Enterprise

transporter room, not quite here yet and not even somewhere else. But

Otto Velez was undeniably here. If not for him, I don't think anyone

would have ever believed there was such a thing as the Toronto Blue

Jays. There

was something sturdy and elemental about Otto Velez. I have no memory

at all of him as a Yankee (apparently he made three plate appearances

in the 1976 World Series, striking out each time), but as soon as he

became a member of the first Blue Jay team he somehow seemed to have

always existed. All the other Blue Jays flickered half-formed like

figures on the malfunctioning pads of the Starship Enterprise

transporter room, not quite here yet and not even somewhere else. But

Otto Velez was undeniably here. If not for him, I don't think anyone

would have ever believed there was such a thing as the Toronto Blue

Jays.

Permalink |

No comments.

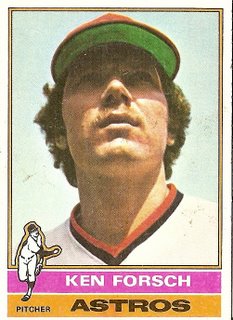

Ken Forsch

2006-09-18 07:21

I

was born in a standard concrete-covered swath of suburban sprawl in New

Jersey but grew up in rural Vermont where we got only three channels:

ABC, CBS, and the punishingly boring PBS. This lent an air of mystery

and excitement to the NBC network, which once every several months

briefly flickered into something other than a swarm of hornets in a

snowstorm. The most prolonged instance of this was when my brother and

I, praying throughout like mediums trying to sustain contact with the

dead, were able to understand most of the proceedings in an extremely

fuzzy broadcast of Super Bowl XIII. But Quark, Land of the Lost, Chico and the Man,

and the rest of NBC's lineup existed as magical but almost completely

indecipherable whispers from another dimension (a dimension that I

assumed was better than the one I was stuck in). I

was born in a standard concrete-covered swath of suburban sprawl in New

Jersey but grew up in rural Vermont where we got only three channels:

ABC, CBS, and the punishingly boring PBS. This lent an air of mystery

and excitement to the NBC network, which once every several months

briefly flickered into something other than a swarm of hornets in a

snowstorm. The most prolonged instance of this was when my brother and

I, praying throughout like mediums trying to sustain contact with the

dead, were able to understand most of the proceedings in an extremely

fuzzy broadcast of Super Bowl XIII. But Quark, Land of the Lost, Chico and the Man,

and the rest of NBC's lineup existed as magical but almost completely

indecipherable whispers from another dimension (a dimension that I

assumed was better than the one I was stuck in).I mention all this because I liked Ken Forsch a little better than Bob Forsch, and I don't really know why. In retrospect, I would have thought it would have been the other way around, since Bob was, like me, the younger brother. But one Ken Forsch versus Bob Forsch theory of mine builds from the thought that the National League was a little like NBC to me back then. In central Vermont, only the Red Sox and their American League opponents offered hints of a life beyond these cards, so I was left to make up the world I imagined the National League to be. In that world, there was something dazzling and full of promise about Ken Forsch's team, the Astros, whereas Bob Forsch's Cardinals struck me as drab and leaden, their time long past. It was like the difference between a new issue of Dynamite Magazine and a National Geographic from a box in the attic. But it's also possible that my slight preference for Ken Forsch is simply because the sound and appearance of the words "Ken Forsch" appealed to me a little more than the slightly more cumbersome "Bob Forsch," the long-voweled "Bob" slowing things up a bit in and of itself and even seeming to influence "Forsch" into being a more sluggish version of its counterpart that hustles along briskly to keep pace with the crisp, swift "Ken," the scrubbed "Ken Forsch" pairing spiriting across an ivy-riddled campus toward a lecture on molecular physics while the thick-ankled "Bob Forsch" duo loiters inside a malodorous Dodge Duster, cow-chewing bread-heavy grinders. Of course, none of this explains why Ken Forsch is gazing at the sky as if he's spent the entire offseason reading Nietzsche. Paul Dade

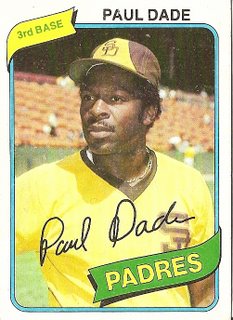

2006-09-17 14:13

Someone

has just called Paul Dade's name. Let me offer an explanation for why

the calling of his name seems to have produced this mixture in his

expression of apprehension, anxiety, resentment, and perhaps a slight

residue of muted curiosity. At the time of this picture, Paul Dade had

shuttled back and forth between different major and minor league

franchises 16 different times in 9 years. He'd been promoted, demoted,

waived, claimed, released, signed, released again, and then, worst of

all, had ended up on the Padres, oblivion's vestibule. Paul, I've got

some news. Paul, step into my office. Paul, we have to talk. This

picture catches Paul Dade on the brink of a 1980 season in which he

would bat .189 and make an error on roughly every 8th ball hit his way.

There are no records for Paul Dade beyond that season. Whoever just

called his name will eventually call yours and mine. Someone

has just called Paul Dade's name. Let me offer an explanation for why

the calling of his name seems to have produced this mixture in his

expression of apprehension, anxiety, resentment, and perhaps a slight

residue of muted curiosity. At the time of this picture, Paul Dade had

shuttled back and forth between different major and minor league

franchises 16 different times in 9 years. He'd been promoted, demoted,

waived, claimed, released, signed, released again, and then, worst of

all, had ended up on the Padres, oblivion's vestibule. Paul, I've got

some news. Paul, step into my office. Paul, we have to talk. This

picture catches Paul Dade on the brink of a 1980 season in which he

would bat .189 and make an error on roughly every 8th ball hit his way.

There are no records for Paul Dade beyond that season. Whoever just

called his name will eventually call yours and mine.

Permalink |

No comments.

Jose Morales

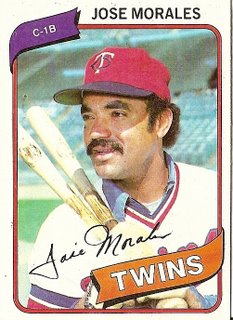

2006-09-16 06:32

I

started kindergarten the same year Jose Morales reached the major

leagues, 1973, and I was expelled from boarding school with one month

left in my senior year in 1985, the year after Jose Morales' quietly

competent, useful career as a right-handed bat-for-hire concluded. That

summer, after taking and passing a GED exam, I moved to Cape Cod to

live with my grandfather, who got me a job at a gas station where I was

required to wear a shirt very similar to the one poking out from under

Jose Morales' uniform. I pumped gas, washed windows, checked oil.

People asked me about problems with their cars and I had to tell them I

knew nothing about cars. I didn't even know how to drive. Also, people

kept swerving into the station, rolling down their windows, and

shouting at me that they were lost. But I didn't know how to get

anywhere except from my grandfather's house to the gas station and

back, and I probably couldn't have articulated even that path with any

clarity. But if anyone had ever screeched to a halt by the pumps

needing to know who owned the single-season major league record for

pinch hits, I could have helped. Jose Morales, I would have declared,

uselessness briefly abating. I

started kindergarten the same year Jose Morales reached the major

leagues, 1973, and I was expelled from boarding school with one month

left in my senior year in 1985, the year after Jose Morales' quietly

competent, useful career as a right-handed bat-for-hire concluded. That

summer, after taking and passing a GED exam, I moved to Cape Cod to

live with my grandfather, who got me a job at a gas station where I was

required to wear a shirt very similar to the one poking out from under

Jose Morales' uniform. I pumped gas, washed windows, checked oil.

People asked me about problems with their cars and I had to tell them I

knew nothing about cars. I didn't even know how to drive. Also, people

kept swerving into the station, rolling down their windows, and

shouting at me that they were lost. But I didn't know how to get

anywhere except from my grandfather's house to the gas station and

back, and I probably couldn't have articulated even that path with any

clarity. But if anyone had ever screeched to a halt by the pumps

needing to know who owned the single-season major league record for

pinch hits, I could have helped. Jose Morales, I would have declared,

uselessness briefly abating.

Jim Bibby

2006-09-15 05:57

Jim Bibby began the 1975 campaign on the Texas Rangers but was traded to Cleveland in mid-season along with Jackie Brown, Rick Waits, and $100,000 for Gaylord Perry. A few months later, Cleveland made another deal, shipping a power-hitting part-time outfielder to the New York Yankees for Pat Dobson. What I'm saying--and my hands are shaking as I type this--is that between those two deals, from June 13, 1975, to November 22, 1975, Jim Bibby and Oscar Gamble were teammates. Jim Bibby began the 1975 campaign on the Texas Rangers but was traded to Cleveland in mid-season along with Jackie Brown, Rick Waits, and $100,000 for Gaylord Perry. A few months later, Cleveland made another deal, shipping a power-hitting part-time outfielder to the New York Yankees for Pat Dobson. What I'm saying--and my hands are shaking as I type this--is that between those two deals, from June 13, 1975, to November 22, 1975, Jim Bibby and Oscar Gamble were teammates.I am incapable of fully expressing my emotions regarding this stunning discovery. I can only point out that in this picture, a young Jim Bibby's already sizable afro appears to be annexing a treetop poking up over the top of the stadium in the background. As evidenced by the calm, confident, slightly mirthful expression on his face, Bibby was aware that he was just getting started, that he was deep in the groove of the process of creating one of the most wondrous monuments of his time. Decades later, grown men on high ledges would be coaxed back into resuming their disappointing existences by the seemingly accidental childhood recollection of Jim Bibby's glorious afro, the embers of awe and glee glowing once more just in the nick of time. While we were in our 20s, some friends and I sometimes passed the time waiting for our lives to begin by drinking beer and inventing entire discographies and rehab-addled histories of various versions of the rock band we would never start, or even really consider starting, none of us with any initiative or musical talent. One of the band names we came up with was Bigger Than Bibby. I suppose we wanted our narrowing worlds to be more, I don't know, mythical or something, as they seemed when as children we held a certain piece of cardboard, our mouths clogged with sugary gum, and gazed for the first time upon what Jim Bibby hath wrought. I think we also were drawn to the impossibility imbedded in the band name--on a certain level, a supremely important or perhaps completely unimportant level that I am spending my life trying and failing to define, there was nothing bigger than Bibby. Except maybe--maybe--Oscar Gamble.

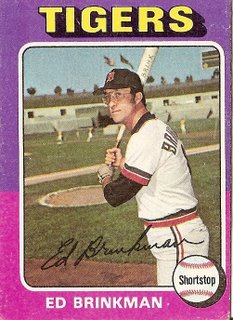

Ed Brinkman

2006-09-14 06:07

The

style used by Topps in 1975 often seemed to produce cards that were

off-center, the bordering almost always thicker on one side than the

other, as if the process of making the cards was not standardized and

mechanized at all but instead one that relied on the judgment and

dexterity of a 19-year-old Coast Guard dropout named Smitty who just

spent his break smoking a joint out by the dumpster. In general, the

mistakes riddling the 1975 set made the universe captured by the cards

seem to my seven-year-old self to be homely, disheveled, approachable,

as if my personal Mount Olympus was barely less tangible than a bake

sale advertised by a mimeographed page tacked to a bulletin board at

the Price Chopper. The off-balance layout is apparent in this card,

which further lessens the feeling of distance between the viewer and

the realm of major league baseball by presenting a figure who seems to

have called in sick to his job as an instructor of remedial math and

driver's ed at the vocational high school to sneak onto the grounds of

the Detroit Tigers' training complex. The distance lessens further

still with the discovery that this bespectacled ectomorph turns out not

to be an imposter at all but a starting major league shortstop;

moreover, he has been a starting major league shortstop for well over a

decade. He even has his own crudely personalized bat, which he

presumably used in the just-concluded season to launch 14 home runs,

his career high. I have to go right now if I'm going to catch the

commuter train that drags me to my job proofreading educational testing

materials; otherwise, I might be tempted to engage in the vice of

making nostalgic claims, such as that the world seemed wider back in

the days when Ed Brinkman was possible. The

style used by Topps in 1975 often seemed to produce cards that were

off-center, the bordering almost always thicker on one side than the

other, as if the process of making the cards was not standardized and

mechanized at all but instead one that relied on the judgment and

dexterity of a 19-year-old Coast Guard dropout named Smitty who just

spent his break smoking a joint out by the dumpster. In general, the

mistakes riddling the 1975 set made the universe captured by the cards

seem to my seven-year-old self to be homely, disheveled, approachable,

as if my personal Mount Olympus was barely less tangible than a bake

sale advertised by a mimeographed page tacked to a bulletin board at

the Price Chopper. The off-balance layout is apparent in this card,

which further lessens the feeling of distance between the viewer and

the realm of major league baseball by presenting a figure who seems to

have called in sick to his job as an instructor of remedial math and

driver's ed at the vocational high school to sneak onto the grounds of

the Detroit Tigers' training complex. The distance lessens further

still with the discovery that this bespectacled ectomorph turns out not

to be an imposter at all but a starting major league shortstop;

moreover, he has been a starting major league shortstop for well over a

decade. He even has his own crudely personalized bat, which he

presumably used in the just-concluded season to launch 14 home runs,

his career high. I have to go right now if I'm going to catch the

commuter train that drags me to my job proofreading educational testing

materials; otherwise, I might be tempted to engage in the vice of

making nostalgic claims, such as that the world seemed wider back in

the days when Ed Brinkman was possible.

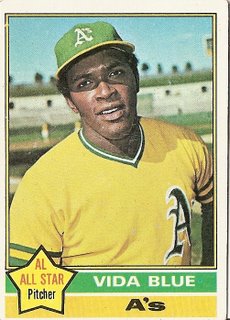

Vida Blue

2006-09-13 06:47

By

the time this picture was taken, Vida Blue had struck out over 300

batters in a single season, won 20 games three times, and helped lead

his team to three consecutive World Series championships. He was only

26 years old and must have felt unbeatable. When I was that age I'd

been sharing a small apartment with my older brother for years and had

begun to worry that he and I were destined to live together forever,

like Miss Emily and Miss Mamie,

the spinster sisters from The Waltons. My brother slept in one room and

I slept on a loft bed in a converted closet. There were

glow-in-the-dark stars on the ceiling above the loft bed, left over

from when previous tenants used the bed for a young child. I worked six

nights a week at a liquor store and got drunk on the weekends, coming

home late to pass out below the dim plastic heavens. By

the time this picture was taken, Vida Blue had struck out over 300

batters in a single season, won 20 games three times, and helped lead

his team to three consecutive World Series championships. He was only

26 years old and must have felt unbeatable. When I was that age I'd

been sharing a small apartment with my older brother for years and had

begun to worry that he and I were destined to live together forever,

like Miss Emily and Miss Mamie,

the spinster sisters from The Waltons. My brother slept in one room and

I slept on a loft bed in a converted closet. There were

glow-in-the-dark stars on the ceiling above the loft bed, left over

from when previous tenants used the bed for a young child. I worked six

nights a week at a liquor store and got drunk on the weekends, coming

home late to pass out below the dim plastic heavens.

Terry Harmon

2006-09-12 07:27

In

1967, the first year listed on the back of this card, Terry Harmon was

the sound of one hand clapping. He had no at bats, no doubles, no

triples, no home runs, no runs, no RBI, and a batting average of .000.

He existed without existing. Other members of the 1967 Phillies, unable

to recall Harmon ever being around, were surprised in later years to

see his grim, robotic visage among familiar faces in the team picture

for that season. There is no listing on the back of this card for 1968,

evidence perhaps that it is possible to do even less than nothing. In

1969, Harmon commenced churning out a few generically forgettable

seasons, blooping enough broken-bat singles in limited action to bat in

or around the low .200s. I don't know if this means anything, but I was

born during Terry Harmon's less-than-nothing season of 1968;

furthermore, the birth occurred in Willingboro, New Jersey, and as far

as I can tell the only Cardboard God ever to have had anything to do

with Willingboro, New Jersey, seems to have been Terry Harmon, who

resided there when this photograph was taken of him reaching for a

groundball that will never arrive. In

1967, the first year listed on the back of this card, Terry Harmon was

the sound of one hand clapping. He had no at bats, no doubles, no

triples, no home runs, no runs, no RBI, and a batting average of .000.

He existed without existing. Other members of the 1967 Phillies, unable

to recall Harmon ever being around, were surprised in later years to

see his grim, robotic visage among familiar faces in the team picture

for that season. There is no listing on the back of this card for 1968,

evidence perhaps that it is possible to do even less than nothing. In

1969, Harmon commenced churning out a few generically forgettable

seasons, blooping enough broken-bat singles in limited action to bat in

or around the low .200s. I don't know if this means anything, but I was

born during Terry Harmon's less-than-nothing season of 1968;

furthermore, the birth occurred in Willingboro, New Jersey, and as far

as I can tell the only Cardboard God ever to have had anything to do

with Willingboro, New Jersey, seems to have been Terry Harmon, who

resided there when this photograph was taken of him reaching for a

groundball that will never arrive.

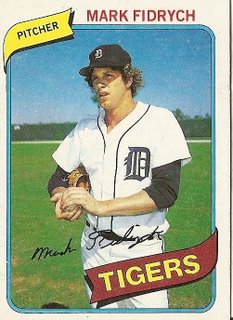

Mark Fidrych

2006-09-10 11:40

In

this picture, taken in 1980, Mark Fidrych attempts to simultaneously

hide and caress a baseball in his hands as if cradling a beloved and

terminally ill pet in a veterinary waiting room. He is four years and

several trips to the disabled list removed from giving the world, in

terms of sheer joy, the greatest single-season performance in baseball history.

The marginalia on the back of this card clings desperately to that

year, 1976, like a profoundly lonely middle-aged man still masturbating

to the image of a beautiful woman he somehow lucked into a brief fling

with the summer after college ended. Fidrych's rookie of the year award

for 1976 is mentioned, as is his 2 innings pitched in the 1976 all-star

game, and the space-filling cartoon along the left-hand border features

a baseball player, generic except for the curly Fid-fro billowing out

from under the hat, holding a giant trophy entitled "1976 MAJOR LEAGUE

MAN OF THE YEAR," an award I've never heard of (and I've wasted much of

my life poring over the baseball encyclopedia like a rabbi reading the

Torah). The statistics alone are left to tell about the other years: in

1977 he pitched in only 11 games; the next year he pitched in only 3;

and in 1979, the last season listed on the back of this card, Fidrych

pitched his fewest innings yet, just 15, losing three games, winning

none, and getting battered for 17 runs, all earned. In this picture,

taken in 1980, it is over. I was 12 years old when I first looked at

this card, in which the fallen god, the all-time single-season leader

in joy, seems to have literally signed his name as "Mush." In

this picture, taken in 1980, Mark Fidrych attempts to simultaneously

hide and caress a baseball in his hands as if cradling a beloved and

terminally ill pet in a veterinary waiting room. He is four years and

several trips to the disabled list removed from giving the world, in

terms of sheer joy, the greatest single-season performance in baseball history.

The marginalia on the back of this card clings desperately to that

year, 1976, like a profoundly lonely middle-aged man still masturbating

to the image of a beautiful woman he somehow lucked into a brief fling

with the summer after college ended. Fidrych's rookie of the year award

for 1976 is mentioned, as is his 2 innings pitched in the 1976 all-star

game, and the space-filling cartoon along the left-hand border features

a baseball player, generic except for the curly Fid-fro billowing out

from under the hat, holding a giant trophy entitled "1976 MAJOR LEAGUE

MAN OF THE YEAR," an award I've never heard of (and I've wasted much of

my life poring over the baseball encyclopedia like a rabbi reading the

Torah). The statistics alone are left to tell about the other years: in

1977 he pitched in only 11 games; the next year he pitched in only 3;

and in 1979, the last season listed on the back of this card, Fidrych

pitched his fewest innings yet, just 15, losing three games, winning

none, and getting battered for 17 runs, all earned. In this picture,

taken in 1980, it is over. I was 12 years old when I first looked at

this card, in which the fallen god, the all-time single-season leader

in joy, seems to have literally signed his name as "Mush."

Permalink |

No comments.

author notes

2006-09-09 08:17

Bats: R Throws: R |