|

Monthly archives: April 2008

Interview with Cait Murphy, author of Crazy '08

2008-04-30 04:35

"Maybe it was just a ball game. But it didn’t feel that way." – Cait Murphy, Crazy ’08 I was recently asked to name my ten favorite baseball books. Despite never veering from my lifelong habit of reading about baseball, my list has remained the same for quite some time, so I immediately rattled off what I thought was my impenetrable murderer’s row as if I was reciting the alphabet. I may as well have pounded my fist on a podium as I answered. My immortal list! It shall never change! A few days later, I started reading Crazy ’08, Cait Murphy’s electrifying tale of the 1908 major league baseball season. The narrative of her insightful, irreverent, illuminating book barrels forward like a high-speed train through a wonderland—you want the train to slow down so you can study the wealth of details flying by, but you can’t help charging ahead to see what’s around the next corner. Even before I was finished I knew the book would be hurtling like that train, or like Ty Cobb, spikes-high, into my personal top ten. I haven’t yet had the privilege of speaking with any of the other authors on my list, but happily for me the newest member, Cait Murphy, was kind enough to answer a few questions about the book, the 1908 season, and her own history in the game. Before turning to the conversation, here’s a brief glimpse of the riches of Crazy '08, from a description of the moments before the season-ending game between the Giants and Cubs that would decide the greatest of all pennant races. Larry Doyle is the first Giant regular to take the field. The youngster gets a warm round of cheers. He has had a good year . . . Q: You start your book by saying that 1908 is the "best season in baseball history." After reading the book, I have to agree. Can you say a few words to back up this claim for anyone who has yet to have the pleasure of reading Crazy ’08? A: It’s the combination of a great year between the lines (both pennant races go down to the last day; the Merkle game and tons of great games and funny incidents); great personalities (Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb are all in their prime; Walter Johnson has his first good year and Cy Young his last); plus developments off the field. Of the latter, the most important, I think, is construction of Shibe Park, which opens in 1909. It is the first modern baseball stadium, and a huge leap forward for the game. Q: You compare a baseball season to a Dickensian novel, and one of the great pleasures of the book is getting to meet the vivid cast of major and minor characters that collaborated on the unforgettable season. Who are some of your personal favorite minor and major characters from that season, and why? A: I really like Jimmy Sheckard, who was an outfielder with the Cubs with a rather waspish sense of humor, and of course Germany Schaefer of the Tigers was regarded as the funniest man in baseball. I have a soft spot for Bugs Raymond, who gave up fewer hits per inning than Matty – and lost 25 games for the wretched Cardinals. Q: Practically every paragraph of the book is bursting with rich, lively details, and yet the book never bogs down into a dry recounting of facts, the details always feeding the story. You obviously did a tremendous amount of work uncovering all the details. What sources were most helpful in gathering these details? Also, was it difficult to incorporate the avalanche of facts and anecdotes into a focused narrative? A: Believe it or not, I left a lot out! The most important sources were newspapers and magazines of the era, particularly the NY Herald and the Chicago Tribune; Baseball magazine; Sporting Life and Sporting News. I put together a detailed chronology using all these sources (and others) that allowed me to see at a glance what the different papers were saying on the same day. That was the core of the research. Q: Besides the details, the most arresting feature of the book is the authoritative, salty, funny voice, which helps bring the past alive in ways that few historical books are able to. Did you have the voice for the book from the start of your work on it, or did you discover it gradually as you went along? Also, was this voice inspired in any way by the entertainingly colorful sportswriting style of the early twentieth century? A: Well, my family says that when they were reading the book, they laughed because it sounds very much the way I speak; so I think I came by the voice honestly. I very much wanted to stay away from the hushed-reverence school of baseball writing. Q: I’m interested in hearing a bit about your own history in the game. Were you a big baseball fan growing up? A: Yes. I’m a Mets fan. Like many people, I inherited the love of the game from my dad, who grew up not far from Wrigley, where his upstairs neighbor was Gabby Hartnett, the great catcher. He moved to NY as a boy, rooted for the Giants, then transferred his allegiance to the Mets when the Giants left for California. So I grew up in a Mets house. I now live in New York City, and have tickets for 14 games this year, which for me will be a record. Q: What do you remember about your first major league baseball game? A: It was 1969 and going to a game was my birthday gift. It turned out it was Cap Day, though, and the only seats we could get were way, way up. My parents were concerned that I would be disappointed. I was not – just enchanted by the whole thing. I wore my best outfit, and seeing that expanse of green bowled me over. Q: You were one of the first girls to play little league. How did you do? A: I was a scrappy second-baseman; average for the league. Q: What is your favorite little league memory? A: Well, our team wasn’t very good; I think we went something like 3-10, so winning our first game. Q: Did your interest in baseball history start at a young age? A: Yes. I was about 10 when I read The Glory of Their Times for the first time, and something about that really struck a chord. Q: Do you have a favorite book about baseball history? A: The Glory of Their Times and Babe by Robert Creamer Q: In your book I was interested by, among many other things, the description of fan behavior in 1908. In what ways would you say fan behavior and the way fans follow baseball now differs from 100 years ago? A: Fans are much more partisan now; they root for the home team, and would never consider applauding a nice play by the opposition. (I think the Phillies fans take this too far; I was revolted earlier this season, when they cheered when Jose Reyes got injured – he hit his head and could have been seriously hurt). Also, today’s stadiums are much more tightly policed, so there is less room for spontaneity. Sometimes a good thing – harder to throw bottles and punches – but perhaps a little too much. Q: One of the themes of the book is that baseball left its childhood behind in 1908. The embodiment of the crueler connotations of this transformation is the teenaged Giants reserve, Fred Merkle. What was life like for Merkle after his baserunning error helped hand the Cubs the pennant? A: Merkle was a solid ballplayer; he played for another 15 years or so, hearing the term "bonehead" regularly. He retired to Florida, had some difficult times (including the "B" word) but I think found some solace when he returned to NY for an old-timers game in 1950—and was cheered. No question Sept 23, 1908, was a life-changing moment for Fred, and not in a good way. Q: It’s now 100 years since the Cubs last won a World Series. What do you think Frank Chance might say about such a painfully long drought? A: I couldn’t print it. Q: What do you think about the Cubs chances this year? A: Intriguing team in a weak division; they should make the playoffs, and then it’s a crap shoot. The key may be Kerry Wood. Q: From what I’ve seen here in Chicago, though the Cubs fiercest rivalry is with the Cardinals, Cubs fans still seem to loathe above all other teams the National League squad from New York. Conversely, from my years of living in New York, I saw that Mets fans harbor no particular ill will for the Cubs. Why do you think this is in 2008, and was there any trace of a similar unequal dynamic in 1908? A: In 1908, there was no question that the Cubs and Giants were baseball’s fiercest rivalry, and it worked both ways. Today, you’re right, Mets fans have no particular animus for the Cubs, probably because the Cubs have never been much of a threat. Q: Do you have any plans to write another baseball book? A: Not at the moment; I am working on another book, this one about two 19th century NY lawyers. I am not opposed to writing a baseball book, but have not come up with a subject. Ideas are welcome! (First published in 2007, Crazy '08 is now available in both hardcover and paperback.) Steve Howe

2008-04-28 08:17

I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. When I saw the name I got the same feeling, not felt by me for decades, that my collection was built upon, that excitement of finding a desired new card, a name that I knew but that was not yet part of the collection, that feeling that a hole was being filled, that what was missing had been found. I brought the card home and added Steve Howe to the Cardboard Gods. Turn Back the Clock

2008-04-25 09:33

"The commercial overproduction of souvenirs means that you’re inculcated with nostalgia before you’re even old enough to feel nostalgic." I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. VIII. IX. Steve Carlton in . . . The Nagging Question

2008-04-22 10:09

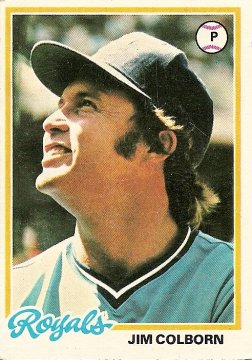

By way of contrast to the Jim Colborn card I posted yesterday, which featured a sun-drenched photo that stands as one of the most aesthetically pleasing displays in my entire shoebox of messages from the gods, here is what may well be the ugliest card I own. Centering the ugliness is the bright red blob mushing down one of history's more ill-advised perms while also somehow (the cap seems brimless and even hyper-real, as if it’s a smudge of card-doctoring Day-Glo paint) shadowing the unappealingly sharp, avian features of the subject’s ashen face, his smile strangely off-putting, verging on an acidic grimace, his neck wrinkled, the top of his chest appearing clammy, clinging uncomfortably (one can’t help but imagine) to the chafing polyester of the cheap candy-striped uniform. From there it just gets worse. The blur of gray sky behind him, such an awful contrast to the spring blue most often seen in my other cards, seems less like sky than hardened Kaopectate. The green border of the card furthers the dismal effect. The drab block lettering along the top of the border somehow sucks all the joy out of the all-star distinction it proclaims, and the yellow block lettering of the player’s name along the bottom turns what could have been a moment of gleeful recognition of a superstar into a vague but visceral yellow-green unease. The bulbous, crudely-rendered cap icon on the lower left, a leaden image made even less appealing by the joyless block lettering jamming the crown, helps drag the overall impression of the card into that of a senseless dumping ground. This impression is clinched by the presence of the baseball icon in the lower right, a brand new lawyerly blight on the cards that season, 1981, when Topps by court order relinquished its benevolent monopoly on baseball cards, the icon signaling that everything—even baseball cards, those potent symbols of innocence—is a fight, a grab for power, that the noise and clutter of the real world is going to start encroaching on the realm of the Cardboard Gods. And though I’m sure the odd ugliness of the card surely undermined any excitement I might have had at finding an all-star in a pack—it may be no accident that it was the last all-star card I would ever receive, my buying of cards dropping off precipitously that year—the ugliness has increased over the years with further knowledge about the reclusive man pictured in the card. As reported in a 1994 article by Pat Jordan, Steve Carlton believed, among other things, that world events were heavily influenced by “12 Jewish bankers meeting in Switzerland” and that the AIDS virus was created "to get rid of gays and blacks.” Carlton denied that he made these claims, but because of Jordan’s journalistic reputation it’s hard not to add at least a dash of execrable wing-nut seasoning to the rancid stew presented in this card. * * * Today the promising new Virile Lit website is featuring my review of the great recent Pete Maravich biography by Mark Kreigel. In the review I pose the following question: If you could have the skills for one day of any athlete from any time in history, which athlete would you choose? My answer, given the subject of the review, will not surprise you. But it got me thinking about limiting the question to baseball. And while nobody from the world of baseball sprung immediately to my mind upon reshaping the question, my first thought on the subject rendered one certainty: Left-handed. I’d want to be left-handed. This fascination with the southpaw has been with me since I started following and playing baseball. Many a time I went into a windup in front of a mirror just so I could watch myself as a lefty. Lefties were different from me. Lefties were more graceful and smooth, their bodies seeming to more fully and deeply hew to the demands of whatever motion the game they were involved in required. I saw this in the whipcrack serve of John McEnroe, in Fred Lynn's ability to in one smooth motion catch a flyball over his shoulder on the run and whirl to throw it back to the infield, in the fast, balanced, lethal swing of Ted Williams. But nowhere was the uncommon grace of the left-hander more apparent than on the pitching mound. Oddly enough, though I don’t have a distinct memory of Steve Carlton’s windup, I do not associate it with the symmetrical poise and balance of, say, a Ron Guidry windup. When I think of Carlton the pitcher I recall first his brutal training regimen, which included most notably him churning his arm around for hours in a vat of rice, then I think of his most renowned pitch, a nasty slider, and the general impression in my mind is not of effortless grace but of grunting herky-jerky exertion leading to the stinging pain of a bat sheared off at the handle. And even though in the terms of today’s Nagging Question I’m not imagining myself into the batter who would feel that pain (and failure) in his palms, I still don’t want to dream myself into a situation including that pain. In other words, I’d want to be a lefty, just not the permed Lefty pictured above, even though he’s probably the second-best Lefty in the history of Lefties (after Grove). I considered choosing Sandy Koufax, but there, too, is pain, all those stories of him having to slather himself with scalding balm before games and plunging his throbbing arm in ice for hours after games. Grove himself might be a good choice, but I associate him with ferocious intensity that at times boiled over into locker-wrecking post-game tirades, so as good as he was I’d want to avoid spending my one day with legendary skills in a fugue of blinding, volcanic anger. Instead, I’ll go back even further, to the very first great lefty, one who didn’t clutter up his prodigious gift with any apparent anger or even much effort. He just wound up and fired and blazed pitches past batters at a rate so far above that of other pitchers of his time that even without looking I feel fairly certain that, in a historical context, he was the greatest strikeout pitcher who ever lived. And by what little I’ve read about him, he was not an unhappy fellow, and certainly would never have thought to spend hours gruntingly churning his arm around a vat of rice or devising Jew-related world conspiracy theories. He’d rather run after firetrucks! Yes, if I could be any baseball player from history for one day, I’d be that long gone simple-minded left-handed marvel Rube Waddell. And now, finally, I’ll pass the question on to you: If you could have the skills for one day of any baseball player from any time in history, which baseball player would you choose? Jim Colborn

2008-04-21 10:09

What’s your story? This seems like something a woman might have said to me at some point in my life, a sort of rhetorical question intended to serve as a flat palm in my chest, pushing me away, backing me off. Why are you so weird? Why are you so desperate? God, why are you the way you are? But I can’t really think of any instance where these actual words were said to me, except for once when the question was posed by a teammate on a hastily thrown together ultimate frisbee tournament team. We had gone from Brooklyn up to some fields on a military base in Massachusetts to play a bunch of games, and actually we ended up getting brutally annihilated in all of them, each loss worse than the one before it because we were short-handed, disorganized, and running ourselves into exhaustion. I had had misgivings about going to the tournament because I wasn’t in great shape and hadn’t been playing much ultimate for a while, and as it turned out I should have listened to those misgivings. I was the worst player on the team that weekend, and by the end of the first day I could barely move. I was lying on the bed in one of the hotel rooms we’d rented. For a while a bunch of guys were hanging out there, then I guess some of them went to get food. I was unable to move and stayed. One other guy stayed, too, sitting in a chair by the television, and after chattering for a while he asked me the question. "So what’s your story?" he said. I didn’t understand. The question wasn’t asked in a hand-in-chest, "what’s your problem" kind of way, but sincerely, as if he wanted to know, so I thought he was inquiring curiously about my unusually aimless existence. (All of the guys on the team but me had professional careers of one sort or another.) I started muttering something, but before I could get many words out he blurted his own answer for me. "Just hanging out, huh?" he said. "Uh, yeah," I said, not really sure what he meant by either the words themselves or the dismissive abruptness with which he’d said them. He was an intense fellow. I remember once, during a pickup game in Prospect Park, some guy’s kite had plummeted from the sky and hit him in the head. He snatched up the kite and stormed toward its owner, and he probably would have jammed that classic symbol of peaceful lazy summer days down the kite owner’s throat had both teams not intervened to stop him. Anyway, he stomped in a similarly intense way from the "what’s your story" question to other matters, burying it, and it wasn’t until much later that I realized he was asking if I, like he, was gay. The second day of the tournament went even worse than the first. At one point during one of our second-day defeats a teammate yelled at me for failing to run down a fluttering pass. I still have fantasies of feeding that guy to sharks or dropping a piano on him. He was a graduate of the hippie college Hampshire and knew how to fix the engine of his car and he didn’t even know me except to yell at me. Who the fuck are you to yell at me? I wanted to ask. I never did. I also thought, Who needs this? I was in my late twenties by then and certainly had no desire to be yelled at by anyone, especially able, resourceful, self-reliant Hampshire engine-fixing fucks. God how I hate that guy. Had we been somewhere where I could get home on my own I would have walked off the field right then, but quitting in that situation was problematic. I could have stormed off, but I would have had to come back and get a ride from one of the teammates I’d abandoned. So I stuck it out, feeling physically and mentally miserable. At the end, I got a ride back to Brooklyn with the intense gay guy because he was leaving right away while the guys I’d ridden to the tournament with were staying to watch the tournament championship game. During the ride I found myself talking about girls a lot. Girls I’d dated, relationships I’d had. Girls, girls, girls! Did I mention girls? I sounded like an idiot, but I couldn’t help myself. By then I’d realized the nature of my teammate's question the day before and I guess I wanted to convince him—and more importantly, myself—that I was, as the asinine saying goes, "all man." So that’s my story, or part of it anyway. I can’t tell you why I ended up digressing down that uncomfortable avenue, but the reason I’m pondering the question "what’s your story" is that I’ve been wondering lately about the essentials of my story. I’ve been trying to find the line through all these baseball cards. What’s the story here? How would I boil it down to what I guess they are calling these days an "elevator pitch"? Or is it, my life, my story, all just a big mess, just a box of unsorted cards? I've really been trying to answer this question most of my life, and most of the time the answer comes out in a minor key, my story one of shadows and confusion and uncertainty and loss. But why can’t the story also have sunlight? I know it’s there. I know there have been times when I’ve felt it shining down. Which leads me, finally, to the smiling, sun-drenched visage of Jim Colborn. Colborn had been playing a while at the time of this card and had before now one season of what looked like unusual, inexplicable success, winning 20 games for a bad Milwaukee Brewers team. It must have come to seem to him as if that season had been an aberration, that he’d always play mediocre baseball for mediocre teams, but then he was traded to the Royals and chipped in 18 wins—one of them a no-hitter, the ultimate moment in the sun—for an outstanding team, a team that had everything: speed, some power, great defense, good pitching, all of it good for 102 wins for the Royals that sunny glorious summer. It all ended abruptly soon after, the next season, with a midseason trade to the Mariners and beyond that nothing, no more major league games. Done! One minute you’re pitching no-hitters and smiling in the sun and the next minute you drop out of the record books. But why does the end always have to be the story? Why can’t the moment in the sun be the story? Speaking of endings, that ultimate frisbee tournament was the last organized sporting event I ever took part in. It was a bad way to go out: The worst player on a terrible team, by the end my body so beaten I couldn’t even move to catch a throw even a few feet away and got yelled at by a prick. That haunted me for a while, the fact that I went out a loser, but by now enough time has passed that I can sort it into its place. Just because it was the last time doesn’t mean it has to be the whole story. There were other, better days. I even caught the tourney-winning pass once. It was the lesser "B" division wing of a minor tournament in a sport few take seriously, but by god we still won when I snatched that disc out of the air in the end zone for the clincher. My teammates even sort of swarmed me for a couple seconds. It was the second and last time I’d ever been surrounded by teammates, the first since years earlier, in little league, when I’d somehow driven a ball just barely over the left-field fence, the greatest memory of my childhood. The game-winning catch wasn’t on the same level as the little league home run, but it was still pretty good. I held onto that frisbee for quite a while, long after the ragged victory scrum had dissipated, even after most of my teammates had started the long walk across the fields to the parking lot. Tony Solaita and Craig Kusick

2008-04-20 07:49

It’s Sunday and I haven’t written in long enough that I’m starting to worry if I’m done so the thing to do is go straight into the silence and start thrashing. This is what I would tell someone I cared about if they were in the same predicament: just write and let it flow and don’t worry if it comes out stupid, for you as everyone is are full at all times with the immensity of the universe, etc, etc, and all that remains is the practice of opening to it so open to it with sincerity and love and in the name of Jack Kerouac and his tenets of spontaneous prose just go. OK. So. The men pictured here. The two men pictured here are done. I mean they played no major league baseball the season these cards came out or ever after. Also, they have both passed away, Kusick at the age of 59 and just months after his wife died and Solaita even younger, shot to death in his native American Somoa. They had somewhat similar careers, both playing sparingly for a few years in the early 1970s before becoming semi-regulars in 1974. Solaita was a left-handed batter who had trouble hitting lefties, and Kusick was a right-handed batter who had trouble hitting righties. Neither was ever a full-time player, but for a few years they were productive part-timers. They both came to the Toronto Blue Jays at the end of July 1979. The Blue Jays were well on their way to their third 100-loss season in their three years of existence. In fact, they would end up losing more games in 1979 than in either of the previous two seasons, which must have made it seem that they would never get any better, that they would languish forever in the basement. Kusick and Solaita did little to contribute either way. Maybe this was the plan all along, just bide time while the young guys slowly mature. The Blue Jays did get better eventually, becoming a good young team throughout the 1980s and then a championship team in the early 1990s. Maybe in 1979 they just needed bodies, and it didn’t matter if you were half a ballplayer or a whole ballplayer. Together, Kusick and Solaita made a whole ballplayer. On their own, they were aging, limited, slow, flawed. They were backup designated hitters. They sat behind two other aging slow sluggers, Rico Carty and John Mayberry. But I have not written for days. This bothers me. The less I write the more I wonder if I’ll never write again. I can’t think of anything to say and also have everything to say. I wasted my day yesterday and I worry that I’m wasting my life. How long can I last? I just read Pete Maravich’s biography and he died when he was my age, 40. John Marzano, who I remember as a hero in the only bench-clearing brawl I’ve ever witnessed in person, died a couple days ago, not much older than me. He had a heart attack and fell down the stairs. Back in 1991, my brother and I made a trip up to Boston just to see the Red Sox, and Clemens was pitching, and he got taken deep a couple times early and took out his frustration on the next batter, John Shelby, drilling him. Shelby rushed the mound, bat in hand. Who knows what he would have done with the bat? Had Marzano not gotten one of his rare starts at catcher that day we might have found out, and maybe Roger Clemens would be living in a 24-hour care facility, his brain sluggered, John Shelby buried in some prison somewhere. But Marzano tackled Shelby from behind just feet from Clemens. The picture in the Boston Globe the next day brought tears to my eyes for some reason. It was all there—Shelby, the bat, Clemens, Marzano heroically taking Shelby down. The hero! I have this need for heroes, I guess. As I’ve made abundantly clear, repetitively clear, probably, my first hero was my brother. My favorite times playing in the yard with him were when we pretended to be a team together. He’d throw the passes and I’d catch them, or vice versa. Touchdown! But this was boring to him. Music was the same way. I listened to what he listened to, for the most part, always lagging a little behind and then at times inhabiting the just-abandoned step of his path with an intensity that outstripped his own, making it my own only by means of skewed worship. This is bullshit! Why can’t I be coherent? The thing is in 1979, the year Kusick and Solaita became one whole ballplayer between them on one of the worst major league baseball teams in history, disco was dead. We had listened to disco together, my brother and me, together. We owned the Saturday Night Fever record jointly, as I recall. Also we once had a dispute over who would get to buy Leif Garret’s single "I Was Made For Dancin’." But by 1979 my brother had moved on to Rock with a capital R. His blue three-ring notebook was covered with Rock names. That summer we went to New York City to visit our dad, as we always did, and the highlight of the visit for my brother was a Ted Nugent show at Madison Square Garden. Somehow he convinced our dad to take us to the concert. I didn’t know any Ted Nugent. I went along. It was terrifying. There were these older guys sitting in the seats behind ours, and they were resting their booted feet on our seats. They moved their legs slowly, reluctantly. One of them wore a cowboy hat and dark shades. I felt very awkward and scared and out of my element. There were disco sucks signs. There was one sign that two guys carried around that said "Disco Is Dead But Rock Is Rolling." The band came out. It was deafeningly loud. It was painfully loud. I couldn’t fathom how loud it was. Worse, each loud sound pained me in a way I can’t quite explain but that had to do with my father. I knew he was suffering immensely. Also, I don’t know, I didn’t... I’ve never really figured out why it pained me so much. We went into the bathroom, my dad and I, while the show was still going on. The bathroom was completely empty. I told him I was sorry. He didn’t hear me. I repeated myself a couple more times. He finally nodded as if he’d heard me, but I think now that he was just sick of trying to decipher my mumblings. He had cotton stuffed into his ears through the whole concert anyway. But why was I apologizing? I mean, I was really mortified by the whole thing. I really did feel sorry. But why was I so guilty about his presence at the concert? I hadn’t even been the driving force on the thing anyway. I was just going along with my brother. It was torture, the whole thing. I remember a couple things about the show. I remember one longhaired young dude of Rock turning to another in front of us and giving an appreciative, "these guys are not bad at all" nod. This only really made sense afterward, when we found out the details of what exactly we were seeing. I remember that the one scrap of lyrics that I could pull out of the general painful noise was "sin city." The singer kept repeating those words, sin city. And at the end, or near the end, the shorts-wearing guitarist got up on the singer’s shoulders and they waded out into the crowd, the guitarist soloing. As soon as they finished their set my dad stood and marched us out of the Garden. No one else seemed to be heading for the exits; in fact, some people seemed to still be straggling in. I remember crossing the mostly empty avenue and asking my brother, my voice sounding weird and small after all the shrieking decibels, "So which one was Ted Nugent?" I didn’t know Ted Nugent very well, but I recalled from one of my brother’s album covers that he carried a guitar and also seemed to be singing, or at least screaming, into a microphone. The act we had just seen, which we assumed was Ted Nugent, had a singer who did not play guitar and a guitarist who didn’t sing. I think my brother and I exchanged a couple thoughts along these lines and then fell silent. The next day we went to Crazy Eddy’s on Sixth Avenue and thumbed through records by AC/DC. I guess we didn’t really understand how concerts worked, because for some reason we were holding out hope that we hadn’t missed the very act we had been trying to see even as we understood, I guess probably by looking at our tickets, that there was an additional act somehow involved with the concert. Anyway our foolishness didn’t become official until I located the song "Sin City" on one of AC/DC’s albums. Of course, pictures of the shorts-wearing guitarist were all over their albums too. We were the stupidest motherfuckers in the history of the planet. My brother ended up writing an essay about the concert for an English class that fall. He didn’t let on that we hadn’t seen Ted Nugent, not to his friends and not in the essay. He got a lot of praise for the level of detail in the early parts of the paper and was criticized for his vague description of the Ted Nugent part of the paper. As for me, I never really did get into Ted Nugent beyond buying a cassette by him that included Wango Tango and Terminus Eldorado. But within a year or so I had become a huge AC/DC fan. They got big right around then anyway, Highway to Hell’s big success giving way to Back in Black’s monstrous status as one of the biggest, greatest albums in all of the history of capital R Rock, but I think part of my interest in them was due to seeing them in concert, not because the concert had been enjoyable but because it had been huge and frightening and painful, and by learning all their music by heart I mastered that chaos, brought it inside myself, made it my own. Interestingly enough, my brother never really got into AC/DC as much. His music tastes changed, shifting toward new wave and punk, and while I followed him into that I did so taking AC/DC along. AC/DC was mine alone. I was 11 that year, 1979, and in a way I was done. Tony Solaita and Craig Kusick were done that year and so was I, done with grade school, done with childhood. Puberty followed, AC/DC the perfect soundtrack. It was dim-witted, the music, and straightforward, pulsating, angry, explosive. Uncertainty and shame and guilt and fear all dissolved in the span of one of their 4-minute three-cord stomps. Angus Young, the shorts-wearing guitarist, became a new hero, the schoolboy gone wrong, expelled for bad behavior, unrepentant. On the cover of Highway to Hell the band looked like cavemen. The two-guitar attack was the best part of the music, the older brother Malcolm Young laying down the riff and sticking with it unwaveringly like a starving Neanderthal bashing a rock on ice, Angus following the riff until a crack formed and then stealing though the crack to a wilder wider life with his incendiary solos. God they were good. God they were idiots. My two favorite bands when I started getting hardons and learning new forms of loneliness were AC/DC and the Ramones, bands of brotherly impassioned idiocy and stomp, riffs to burn your brain clean. The seventies were done. I was done. Touchdowns in the yard with my brother were done. I was half of a whole. And disco was done. And Rock was rolling. Gene Michael

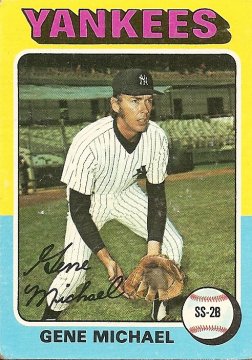

2008-04-16 11:37

Gene Michael became general manager of the Yankees in 1990, the same year I left college and moved to New York City. In those days, my brother and I occasionally rode the subway from Brooklyn up to Yankee Stadium, sometimes to quietly and uneasily root for the Red Sox, sometimes just to see some baseball featuring any random visiting team. At that time the Yankees were bad enough to allow a guy to spread himself across three seats and sit in the sun and watch a game and not have to worry whether the Beast was going rise up and stomp out every cringing nonbeliever in its path. Of course, this did not apply to the games against the Red Sox, which were always packed no matter how irrelevant either team was at the moment, and in those games the Beast was always present, at the very least a grumble, a tremor, a tip of a vast presence waiting to avalanche down on our heads. The Yankees hadn’t been mediocre for an extended period of years since the days when they employed none other than Gene Michael as their regular everyday shortstop. Of course, neither era (the only two extended spans of also-ranness since the arrival of Babe Ruth nearly a century ago) was the fault of Gene Michael. It’s true that as a player he couldn’t really hit, and unlike some other weak-hitting shortstops of the time, such as Mark Belanger, he doesn’t seem to have a widely acknowledged reputation as a particularly good fielder, either. But the Yankees had plenty of other problems. As for Michael, all I personally know him for as a player, besides the vaguely simian, imaginary-giant-phallus-wielding association the photo on this card has ingrained into my subconscious, is that he was once pummeled by one of Carlton Fisk’s fists while Fisk used his other arm to strangle Thurman Munson. Or did Fisk strangle Michael while pummeling Munson? I can never keep that story straight. Either way, Michael played the vital part of the feckless weakling in the tableau that gave us Red Sox fans one of our rare moments of temporary superiority amid all those decades of abject subservience. My brother and I were hoping for another one of those moments when we made our way to Yankee Stadium one sunny Memorial Day in the early 1990s. We watched from high above the leftfield foul line in the upper deck as Red Sox pitcher Danny Darwin gradually surrendered most of a big early cushion by giving up one soaring solo blast after another. The Beast, quieted by the early deficit, grew a little louder with every moonshot. Finally Jeff Reardon was summoned from the bullpen in the bottom of the ninth, and Mel Hall ripped Reardon’s meaty offering high and deep. The shrinking white pill disappeared into the rightfield Though perhaps no one but Gene Michael knew it at the time, Hall was something of a vanishing breed among those Yankees. Spared the dictates of the infinitely impatient George Steinbrenner, who was suspended for several key years during Michael's reign, Michael was able to avoid the twin Steinbrennerian habits of jettisoning prospects and stockpiling fading veterans such as Mel Hall. And Michael's well-guarded prospects ended up forming the foundation of one of the most dominant runs in baseball history, an (insufferable) era when the Beast hardly ever stopped roaring and devouring. In my mind the long roar started that Memorial Day in the early 1990s. After Hall finally touched home plate it took so long for my brother and me to get out of there that I’m not entirely sure I’m not still there, insane, dreaming all subsequent events. We took a wrong turn upon exiting the stadium and had to circle the whole giant palace of horrors through an endless circling thicket of the Beast before we got to a subway. Ashen-faced, our Red Sox caps stuffed in our pockets, my brother and I said nothing, just trudged. I remember seeing one young sunburned and well-lubricated Red Sox fan flailing against the Beast. “Fuck Bucky Dent!” he kept shouting as he stumbled through the heckling throng. Veins stood out in his forehead and his voice cracked. “Bucky Dent sucks!” You poor crazy bastard, I remember thinking, not without some admiration. It was like watching someone try to start a fistfight with an oncoming train. Jack Clark

2008-04-15 09:11

Jack Clark, the last of a series of talented young outfielders that passed through the Giants outfield in the 1970s in the wake of Willie Mays, is shown here as a young wax figure with a face bearing an eerie similarity to the Wicked Witch of the West. Before Clark, the Giants had been unable to win in the post-Mays era despite the burgeoning talents of Bobby Bonds, Ken Henderson, George Foster, Garry Maddox, Gary Matthews, and Dave Kingman. With Clark, they still couldn’t break through and win the division, and eventually they gave up and traded him to the Cardinals for David Green, Gary Rajsich, Dave LaPoint, and Jose Uribe. While these four nondescript professionals did little to dissipate the Giants’ long post-Mays fog, Clark promptly led the Cardinals to two National League pennants in three years, his ability to hit for power in cavernous Busch Stadium earning him a reputation as one of the most fearsome sluggers in the league. He cashed in on this reputation by signing a lucrative free agent deal with the Yankees before the 1988 season. He hit 27 home runs and drew 113 walks for New York that year, but the Yankees, perhaps unwisely choosing to focus on his .242 batting average instead of his power and .381 on-base percentage, shuttled him to San Diego along with Pat Clements for the unimpressive package of Lance McCullers, Jimmy Jones, and Stan Jefferson. A couple years later, after continuing his usual late-career pattern of walking a lot, hitting for power, and missing significant chunks of the season due to injury, Jack Clark came to the Red Sox. He was 35 years old by this time and ready to settle into a role in which he could throw away his fielders gloves and laze around on the bench between at-bats. The Red Sox were coming off a season in which they won the division despite lacking a premier power hitter, and Clark’s arrival sparked skyrocketing preseason hopes. He had been injured a lot of late, sure, but this season (so went the thinking) was going to be different, and by staying healthy all year and having the Green Monster as an ally he’d surely blast 40 home runs and amass 140 RBI as the Red Sox rode his broad shoulders all the way to a long-awaited World Series win. That kind of desperate, ridiculous hope was part of the culture of Red Sox fandom back then. I know I bought into it. I thought Jack Clark was going to be The Man. It didn’t work out that way. It never does. I should know. At that time I was in my early twenties and I applied this kind of straining, suffocating hope to every facet of my life. Every sentence I wrote was going to be the one that sprung open the gates of some as yet undiscovered genius. Every woman who so much as inadvertently brushed against me on the subway or accidentally glanced my way while standing at the bar and ordering drinks was going to be the one to banish my solitude and grace some new redeemed life with undying love. It had a way, this constant grasping for miracles, of saturating the world with disappointment. *** (Love versus Hate update: Jack Clark's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Dave Concepcion in . . . The Nagging Question

2008-04-10 10:38

Dave Concepcion has a special place in my memory because when I was a kid he once appeared on the cover of Boy’s Life, which my brother had a subscription to as part of his membership in the Cub Scouts. This was for me something like finding some Spiderman comic books or a plate of fudge in the socket aisle at a hardware store. The usual contents in Boy’s Life—fixing stuff, building stuff, lighting fires with no matches, performing resourceful courageous rescues, communing healthily with other young capable outdoorsy boys, cataloguing in a manly scientific way the splendor of nature, helping others, etc.—never interested me, so I was pleased to have something in that corner of my brother’s life that I could relate to. I don’t actually know how much my brother enjoyed the Cub Scouts, and in fact I’m pretty sure he bailed out prematurely, right around puberty, after he’d earned a couple but not all of the hierarchical series of patches. But into adulthood he has retained a level of comfort with the tasks of the outdoorsman that far surpasses my own. He knows how to set up a tent and identify a bird and start a fire, to name but a few of the things that I approach clumsily and stagger from frustrated, my glasses askew. For him the wild is a place to go to shrink the tasks of a difficult everyday world to a manageable level while simultaneously widening a sense of that everyday world beyond the confines of the necessary economic trenches most of us dive down into most of our days. I like going into the woods for the same reasons, but the work that needs to be done there always gives me back a familiar sense of myself as a generally incompetent guy. Given this, it occurs to me to wonder where I go, if not the woods, to give myself a sense of competence. The answer is the same now as it would have been thirty years ago, when I was the kid who got excited to see Dave Concepcion on the cover of Boy’s Life. I liked at that time to get away from the world by going into baseball universes inside my head, and the same is true today. What I’m driving at here is that while I may not know how to fix a flat or gut a fish or understand what an IRA is or ballroom dance or tell a joke or build a table, I am, by god, a pretty good leader of imaginary baseball teams in the online Strat-o-matic baseball leagues with player pools based in—where else?—the 1970s and 1980s. I am no Panzer Ace, mind you. (In case you were wondering, Panzer Ace is the unfortunate moniker of the guy who wins just about every league he enters. If inflection of voice were possible in such areas, he would be spoken of on message boards in hushed tones.) But my teams manage to get into the playoffs more often than not. So what’s my secret, you ask? (I am sure this is the first question that comes to your mind, and not, for example, "Doesn't it ever occur to you that one day you'll be on your deathbed wondering why you spent so many hours worrying about imaginary batting orders?") I’m glad you asked. In two words: Dave Concepcion. Well, not just Dave Concepcion. But in my experience building a team around a great-fielding shortstop and a great-fielding second baseman, especially if either or preferably both of them can also contribute to the offense, is the best way to ensure that your team will be competitive. Centering your team’s defense, they make mediocre pitchers good and good pitchers great by gobbling up everything hit to them. And if they can hit, as Dave Concepcion could (or, in my imaginary worlds, still can), they make it much easier to build a lineup without any holes, other spots on the diamond being much more easy to fill cheaply with effective offensive players. I realize that there is nothing more boring than hearing about someone else’s imaginary sports team, so I understand that I may have killed off most readers willing to start off on the trek of this essay by now. But initially my main goal today, believe it or not, was to give my voice a rest and open up a discussion. It’s just taken me a long time to get to the point I intended to make early on: that according to one of my lone areas of expertise, on-line imaginary baseball, the surest way to build a good team is to start with excellence at shortstop and second base. That said, here’s the question nagging at me today, one which has me leaning toward including in my own answer the player pictured at the top of the page: With peak performance and long-term effectiveness having equal importance, which two players made up the best second base and shortstop combination in baseball history? * * * Also, FYI: There’s an interview with me about baseball cards on ephemera today. The fascinating site, which focuses on various types of collecting, is definitely worth a look. Bill Buckner

2008-04-09 09:27

I. He took a drag off his cigarette, his eyes narrowing. He well knew the answer to the question, but he was taking his time anyway. He exhaled. He looked Pete straight in the eye. “Run naked and put up a sign,” he said. II. III. “Who’s number 27?” the dad was asking her, his voice soft. “K-Kovalev?” “Right, sweetie,” the guy said. “And how about 28. Do you know who number 28 is?” “Larmer!” she squealed. They went through the whole team, father and daughter, name by name by name. IV. I wanted to find my fortune. I recall the notebook I started, Josh Wilker’s Millions, featured particularly fevered writing, long unbroken paragraphs suffocating all margins, the words no more eloquent than dumb blood surging through arteries, all of it part of what I imagined might be a novel called Josh Wilker’s Millions but all of it ultimately unusuable and shapeless and just desperate flailing or who knows, anyway the point is I loved then as now and maybe even more then in some wilder way to write and wrote like I was Jacob wrestling the angel and was tossed loose from it exhausted and buzzing and blessed yet still nowhere, just high from my own exertion and exhortation, a millionaire at last in an imaginary and completely solitary, secret, vanishing way, maybe the only true way considering everything, everything, ends in ashes. V. I remember the last moment the best, a faceoff not far from the Rangers’ goal, the Rangers up by a goal, still enough time for something to go wrong. Steady, reliable Craig MacTavish, the last helmetless player (somewhere there’s a teenaged girl from a broken home who remembers, as I do, that he wore number 14), was sent out to take the faceoff, and he won it, and time ran out, and the place went berserk. We spilled out onto the streets. Mark found us and he and Ellen embraced in a kiss reminiscent of the famous V-J Day kiss between the sailor and the girl in Times Square, although as I remember it Ellen’s superior height gave the famous picture’s echo a slight twist, Mark getting dipped. Pete had brought along a miniature Stanley Cup and somehow we suddenly had champagne and Pete kept pouring tiny portions into the Cup and raising it and toasting the names of Rangers from bygone years. The joy-dazed crowd filing by cheered each name. Stars, benchwarmers, failures, goons. Every single name redeemed. This is what it’s going to be like, I remember thinking. This is exactly how I want it to be when the Red Sox win it all. Everyone, everyone, along for the ride. VI. VII. “Love is not a victory march,” the song says. “It’s a cold and it’s a broken hallelujah.” We rode through the rain, some of us with black ink from the free daily gossip rag staining our hands, some swaying half-asleep, some staring out at the crowded highways. Everyone is bound somewhere. Love. Millions. Ashes. Everyone is a name in bold cerulean.

*** (special thanks to Phil Michaels of Catfish Stew for supplying Bill Buckner's 1986 card) Oscar Zamora

2008-04-08 10:11

A few days ago my wife and I were talking about what to do with the ashes when one of us keels over. “You don’t have to do anything with mine,” she said. “What are you talking about?” “I don’t want to be sitting around in some stupid urn.” “What? No, they have to be sprinkled on something.” “Sprinkled?” She laughed at the word. We were both laughing, actually. Sprinkled. The word seemed better suited to a sunny tableau involving laughing children and a Good Humor truck. “Just burn them,” she said. “You can’t burn ashes.” We started laughing some more. What a hilarious topic! “I don’t know. I don’t care,” she said. “Who needs it?” We went back and forth for a while. I finally harangued her into agreeing that I’d take her to Amsterdam and throw her at the door of the place that used to be the club where she danced through her adolescent and young adult years. I’ll keep my own specific requests to myself, but if all goes according to plan my extinction will result in my widow being led away in handcuffs by the Fenway Park police. *** Oscar Zamora toiled in the minor leagues for nine seasons before making the major leagues at the age of 29. He was decent his first season in the big leagues, quite a bit worse the following season, worse still the season after that, and demoted to the minors the next year. At the end of that year he was sold to another team, who brought him back up for one more chance, which he squandered, posting a 7.20 ERA in 10 games, an effort that cast him into the oblivion beyond any back of the card stats. What remains of him in the collective memory is a ditty either written by a sportswriter or sung by Cubs fans or both, depending on which of the various sketchy versions of the past lingering in the ether of the Internet you choose to believe. It was sung to the tune of “That’s Amore” and went like this: When the pitch is so fat, that the ball hits the bat, that’s Zamora. *** What traces will you leave? To date I’ve had a couple things named after me, but both fell into disuse long ago. The first was something called The Wilker, and it was a punishment invented by my high school ultimate frisbee coach. His name was Buzz and he was a surfer dude from Santa Barbara who was getting his phys ed degree from a nearby college, UMass, which he helped lead to the college ultimate frisbee national championship one year. He was probably the best coach I ever had both because he taught me a lot about the sport and because he was a nice guy and with his van and surferly ways made us all feel cooler by extension. But one day I just ditched practice to go to a pizza place and play the Star Wars video game with my friend Julian. I guess I figured that since I thought of myself as invisible then the whole world thought the same, and so no one would notice I was gone. But Buzz noticed, and the next day he gathered up all our frisbees and had me chase down his long throws one after another, which basically amounted to fifteen or sixteen wind sprints in a row. From then on, if anybody did anything out of line or stupid or lazy the team would clamor for them to be given The Wilker. The tradition, such as it was, only lasted the season. The other time I had something named after me was when I was a part-time liquor store clerk in my early twenties with no money and an aura of glowering desperation, and yet I somehow briefly dated a successful, attractive woman. She was, it was later determined, way out of my league. Somehow the whole improbable situation got wrapped up in me getting a $10,000 deal from a British publisher to write a book about Pearl Jam, a band I knew nothing about and didn’t particularly like. I raced around for a while thinking that my life was going to change completely, that I was going to be an exciting, successful, unlonely guy. “You’re so beautiful I can hardly keep my eyes on the meter,” I told the woman one night, quoting Woody Allen. We were riding in a cab to her apartment. “Josh, we need to talk,” she said. “Who the hell are you?” a member of Pearl Jam’s publicity team demanded of me the next day. I was trying to request an interview with the band for the book. “I’m a nice guy,” I think I said. I felt like crying. Kurt Cobain blew his brains out right around then, and once I heard the news I worked it into a gloomy letter of resignation to the nice woman at the British publishing house who had wanted to give me $10,000. I went back to peddling booze and glowering alone. Anyway, from then on the notion of somehow connecting with someone or something out of your league became known among my small group of friends, at least for a little while, as “pulling a Wilker.” Ken Landreaux

2008-04-07 10:20

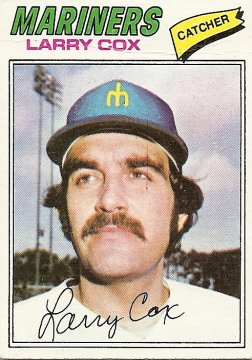

They are tearing up my street. There is a big hydraulic crane ripping up concrete, and it’s really loud and it makes it hard to come up with anything worthwhile to say about Ken Landreaux. Also, my wife is in the bathroom puking. She woke up with some kind of stomach virus and even though she was puking she had to appear in court for her social work job. She’s back now, in the bathroom, steering the bus. I looked up stomach viruses on the Internet. I wanted to see if there was anything I could do. But what can I do? I’m pretty powerless. So I sit here trying to write about Ken Landreaux and when the roar of the crane two inches from my head abates every once in a while I can hear the sound of retching. Actually, since I stared writing the crane has moved up the street a little. I just got up to check on their progress. The crane has carved a swath in the concrete that I swear they just recently put down. They've been tearing up and paving and tearing up and paving the street for months. Anyway the sound has quieted a little but as it abates I discover new kinds of resistance, new anxieties, new ways in which I’m unable to connect to today’s rectangular fragment from my past. There are no names for these anxieties, at least none I can identify right now. Maybe some of it has to do with spring finally arriving. I feel like running around or weeping with laughter or sitting at an outdoor cafe in some faraway place with nothing to do and all day to do it as the gentle warmth melts me. But I also feel apprehensive. It’s been a long winter. I’ve been bracing against the cold for most of my life. So when the warm air comes I can feel all that melting and I can feel the fragile green tendrils of memory, the up-push of tenderness, and it pains me. Better to just stay numb. Better just to continue trying and failing to think about Ken Landreaux. Maybe some of it has to do with Jack Kerouac, who I've been reading lately. Whenever I read him I brace myself for the effect. I’m going to start wondering if my life is too narrow. I’m going to start wondering why right this second I’m not napping in the sun after riding the rails down the California coast, a book of Buddhist scripture open on my chest, or why I’m not this second participating in a raucous epochal poetry reading with "the best minds of my generation," or why I’m not feverishly writing the sincerest wishes from the depths of my soul in the form of a novel that will be published to great acclaim and change the course of American Literature instead of trying and failing to think about Ken Landreaux. I can’t think of Ken Landreaux without thinking of Landru, the computer that dictatorially ruled an alien planet in an episode of Star Trek, brainwashing the creativity, individuality, and spirit out of all the inhabitants and making them a part of one "Body" until Kirk, Spock et al beam down and shake things up, Kirk eventually setting everyone free, as he is wont to do, by riddling the computer into smoldering self-destruction by feeding it an unanswerable contradiction. He did this on several other occasions, including in the tedious "Nomad" episode that seemed to be aired every other night when I was a kid. Anyway, maybe I’m just part of some Landru mind control and don’t even quite know it. This would explain the lack of creativity. Also, I watch a lot of television and spend a lot of pretty useless hours on the Internet, passive pursuits in which I am willingly subservient to one machine or other. Even when I take walks I have headphones in my ear feeding me stupid chatter, usually about sporting contests, i.e., surrogate dramas to take the place of any confrontations or contests in my own life. I am ruled by Landru, limp and docile, wordless and weak, marching in an acquiescent daze. A few years ago I was playing guitar with this guy I knew, Paul, who was an excellent guitarist. We were in his room, noodling around with two of his electric guitars. He said, "Doesn’t it suck when it seems like every solo you play seems like something you’ve already played?" I still pull out my guitar from time to time and play blues licks, but it’s true: I’ve played all the blues licks I know. It’s stagnant, my playing. I remember there was an old poster on Paul’s wall that read "Let go and let God." I wonder what would happen if I let go and let God. Probably nothing. I just tried it for a few seconds, and still couldn't come up with anything to say about Ken Landreaux, but then again maybe I was doing it wrong. Or maybe my problem is Ken Landreaux. I know this is out of line, blaming the subject. If you had Rembrandt paint anything on this earth, it would still be a Rembrandt. It would still be alive with all his pain and wisdom and gloomy reverence for this life. So it can’t be Ken Landreaux’s fault. But all I can think of is that he was traded for Rod Carew. He was traded for Rod Carew. He and a couple other guys, actually, but he was the key element of the trade. He had been a first-round draft pick, had been a minor league player of the year, was still young, and could play centerfield. But the point is I do not have a single Rod Carew card in my collection. I don’t know how this happened. He may have been the best player of the decade, and in some ways he was the most prominent, especially to me, since my religion as a child was baseball and my most concentrated time of devotion was on Sunday morning as I studied the batting averages, and Rod Carew was always at the top. Rod Carew was always at the top but for a couple of years after the trade Ken Landreaux was up there, too, and so it looked for a while like the trade was going to work out for the Twins, especially halfway through the season when the card at the top of the page came out, 1980, the previous season one in which he batted .305, just 13 points lower than Carew, the current season highlighted by a 31-game hitting streak (still the Twins’ record) that would send him to the all-star game and send his batting average skyrocketing as high as .366, surely so high that when I prayerfully studied the Sunday averages I envisioned a future in which Ken Landreaux would take over for Rod Carew as a steady presence in my life, someone who would remain at the top of the list that gave my life a sense that there was a structure to the universe, but instead Ken Landreaux spent the rest of the 1980 season floundering and was traded to the other league where he surfaced as a part-time player on a World Series-winning team, but by then I’d stopped caring so much and Ken Landreaux meant very little, if anything, to me, just a name that used to be a name that was going to be a name. What is there to say? Life unravels. Larry Cox

2008-04-04 09:21

My conscious hours are featureless, my sleep ragged, unearned. I’m a proofreader. Misunderstandings and hurt riddle my dreams. I’m served food I can’t eat, take vague transcontinental airplane voyages with people I haven’t seen in decades. I wake feeling clammy. I ride with strangers, each of us walled off by personal electronic devices. I arrive on time. I sit in a cubicle. I eliminate mistakes. My mind wanders. Mistakes slip through. Huron, Spart’nb’g, Tidewater, Spart’nb’g, Ral.-Durham, Reading, Eugene, Eugene, Reading, Hawaii, Reading, Eugene. Litany of a nobody. Putrid averages, few games played. Larry Cox kept slipping through. When I was 19 I tried to follow in the footsteps of Jack Kerouac but was too timid and just rode a bus the whole way, his hallowed continent reduced to a stock footage scroll across the Greyhound window, mountains giving way to plains giving way to mountains, everything leaden with brown pot and boredom. By the time he was the age I am now the dew of his writing had evaporated and he stayed at home with his mother and watched television drunk. When Larry Cox was 19 the Phillies signed him to a professional contract. Was it a mistake? He hit .219 his first minor league season, which he wasn’t able to improve upon, and then only slightly, until five years later. He eventually had a few at-bats in the majors, but by his late 20s seemed on the way back down, spending an entire year in Tacoma. But instead of disappearing he was bought by a team that did not yet really exist. When he heard the news did he even know of this team which had yet to play a game? Did he wonder if the whole thing was some kind of a mistake? When Jack Kerouac was 29, the same age as the blurred figure in the imaginary hat at the top of this page, he sat down and out of the desperation of not ever being able to say what he truly wanted to say started hammering words down onto a long scroll of teletype paper. The first line he wrote contained a mistake, a stutter, an inadvertent repetition of the word met, the kind of thing that, had he been typing on a computer, would have produced a squiggly line beneath it, an automated alert that already rules had been broken, but he was saved this niggling indignity and anyway there was no time for corrections, life too short, death too close, the only thing to do just move on, a hungering heartbeat: “I first met met Neal not long after my father died...I had just gotten over a serious illness that I won’t bother to talk about except that it really had to do with my father’s death and my awful feeling that everything was dead.” Kerouac wrote those words April 2, 1951, by chance exactly fifty-seven years to the day before I read them in my new copy of On the Road, The Original Scroll. From there he did not stop but gripped the story in his mind as fiercely as a story has ever been gripped and got it all down in a rush, barely sleeping, pouring everything he had onto the scroll from April 2, 1951, to April 22, 1951. I once hoped for similarly immediate deliverance. All through my twenties I ruined days by sitting down at a desk with the hope that I would just start writing and not stop until I emerged from a trance three weeks later looking gaunt and Dostoyevskian and holding a glowing work of genius in my hands. It never happened. I got jobs to get by. I kept trying. I stopped trying. I kept trying. I stopped trying. I stopped trying to stop. I pray for mistakes. Jim Wohlford

2008-04-02 13:22

If Jim Wohlford’s itinerant 15-year, 4-team career was a series of romantic relationships, the first of these affairs, with the Kansas City Royals, was The One. He met the Royals while still practically a kid, full of promise, and they’d grown up together. According to the back of this card, the California-born Jim Wohlford had even relocated to Kansas City permanently. Likewise, a profession of love and devotion had been made to him by the trade of fellow young suitor Lou Piniella so that he, Jim Wohlford, could claim left field for his own. But he did not flourish under the strains of this commitment, and had he been paying close attention he could have noticed that the club, blooming from youthful prettiness to mature division-winning beauty, was growing distant, benching him more and more against righties, beginning to rely on him only occasionally, maybe to pinch-run for John Mayberry, maybe to pinch-hit against Tom Burgmeier. Finally, perhaps just before the photo for this 1977 card was snapped, the Royals, looking better than ever, looking stunningly good, walked up to Jim Wohlford and told him, “Jim Wohlford, sit down. We have to talk.” From then on, if this card is any guide, Jim Wohlford led the league in forlornness, loosing demoralizing sighs as he drifted from one doomed, lackluster relationship to another, his unreliable bat on his shoulder like a hobo's bindle. He tried first to salve the pain of being dumped by the Royals by consorting for a while with a young ripening barroom beauty, the Brewers, before leaving the Brewers just as the club was on the brink of blooming into boozy glory. Maybe any sweet days with the Brewers just reminded him of the Royals, and so were more pain than pleasure, which would explain the embrace, via free agency, by Jim Wohlford of a rainy, joyless three-year numbness with the San Francisco Giants, who eventually jettisoned him for someone named Chris Smith, a name so generic as to suggest the fictional. Last came the sad lingering rendezvous with the fallen foreign-accented former bombshell, the mid-1980s Montreal Expos, who returned Jim Wohlford’s forlorn muttering with cognac-addled rants about Mike Schmidt and Rick Monday and secession. That ended too, of course, as all things will, not long after Jim Wohlford watched from afar in 1985 as the only royal blue heaven he’d ever known won it all without him. Luis Tiant

2008-04-01 08:02

Say you were ten years old. Say your house was robbed. Your Chips Ahoys, your money, your television, your Kiss records, your baseball cards: all stolen. Say the robber kicked you in the nuts and left laughing. Say as you were curled on the floor in pain your mom looked down and told you she had decided to leave to go live in the robber’s glittering house of riches. You would not believe it. You would never believe it. And so this uniform, this cap, this team name on both the front and back of the card, the transactional note on the back that noted the signing by this team of this player in November 1978, a mere month after this team kicked childhood in the nuts, it’s all just an elaborate April Fool’s Day joke. I don’t believe it. I’ll never believe it. |