|

Monthly archives: October 2007

Carl Yastrzemski, 1978

2007-10-29 20:24

The Yazmobile Chapter 3 (continued from Carl Yastrzemski, 1977) A couple years after the dud peyote in Truckee I moved in with my brother, who was living in a tiny railroad apartment on 2nd Avenue and 9th Street in Manhattan. I'd just finished my aimless post-college trip around Europe and I needed money. I got a job as a UPS driver’s helper for the holidays, then when the holidays ended I switched to loading trucks at the UPS warehouse on 10th Avenue and 42nd Street. My shift started in the middle of the night, but for some reason instead of taking the 3rd Avenue bus uptown from 9th Street and then transferring to the crosstown 42nd Street bus I walked the whole way. I set out at around 2 in the morning. Nothing ever happened to me on all but one of the nights, even though for most of the way I walked out of earshot and sight of any witnesses. But one night I got hit by a car. The driver had been blazing up 3rd avenue and made a left-hand turn onto the west-bound street I was crossing. He hit the brakes, but I still got scooped up onto the hood and then tossed back down onto the street. The guy got out, his eyes wide. I struggled quickly to my feet. The two of us stood there, staring at each other. "I’m OK," I said. I said it a few times, trying to convince the both of us. "I'm OK. I'm OK." I banged up my knee pretty bad and ripped my jeans and the elbow of my shirt, but nothing was broken. I walked the rest of the way to work and punched in and worked my shift, my knee hurting more and more as the shift went on. My job was to grab packages coming down a long groaning conveyer belt and sort them into one of four trucks parked behind me. Four other guys also worked the conveyer belt, each with four trucks to load. Five guys facing us worked a second conveyer belt. A cheap boombox played Everybody Dance Now over and over. The guy to my right shadow-boxed during the occasional lulls in packages coming down the line. The guy to my left had an African name and made an anti-Israel comment one night. I was the only white loader, but the supervisor was a harried white guy with a receding hairline and a mustache. He wore a tie and white short-sleeve button-down shirt and was always in a rush. It was tiring, monotonous work. The boxes turned my hands black and all my clothes gray. During the daily 10-minute break, I sat in one of my trucks and read Dante, hell then purgatory then paradise as the months went by. At quitting time I walked home down the west side and cut across 29th Street past towering early morning prostitutes, spent condoms strewn all over the sidewalk like kelp left behind by the receding tide. Near home I yanked a newspaper out of the trash and read it back at the apartment while eating generic three-for-a-dollar mac and cheese and drinking cans of beer, the blinds shut against the morning light. One day near the end of my walk home from that job I stopped at a light and looked across 3rd Avenue and saw my brother standing there, staring back at me. He was on his way to work. He had a heavy duffel bag weighing him down. I had my newspaper from the garbage. We both started laughing. Why not? One minute you're a kid and the next you're chained all night long to a conveyor belt. And your brother, your hero, is lugging a duffel bag full of undone work to an office job where his biggest thrill in many months has been finding and correcting a misspelling of the proper noun Yastrzemski. (to be continued) John Hiller/Red Sox-Rockies Game 4 Chat

2007-10-28 15:36

Their inspirational comebacks (which caused Clint Hurdle to gush in an article today by AP reporter Jimmy Golen that "God's fingerprints are all over a lot of things") follow in the footsteps of a hurler from the Cardboard Gods era, John Hiller. Hiller was sidelined for the entire 1971 season after suffering a heart attack, but in 1973 he authored perhaps the greatest season any bullpen hand has ever had (his 31 Win Shares is the single-season record for a reliever). We never know when we're going to be struck down, so I guess we should never believe we're doomed, no matter what the circumstances, because, you know, who knows? * * * The lineups (courtesy of Extra Bases): Red Sox Rockies Bob Apodaca/Red Sox-Rockies Game 3 Chat

2007-10-27 14:17

In his injury-shortened career as a Mets reliever, Bob Apodaca faced Biff Pocoroba three times. He got him to ground out, then intentionally walked him, then got him to line out. The Mets lost all three games. I don't know what became of Biff Pocoroba after that, but this past Thursday night Bob Apodaca contributed to the continuing disenchantment of the world I marveled at as a child. All my life I have wondered about what is said during pitching mound conferences, but on Thursday my curiosity on the subject shriveled and died, thanks to a running patter of numbingly banal self-help-guru exhortations by Colorado Rockies' pitching coach Bob Apodaca, who had been miked up for the game by Fox, part of the seemingly unstoppable trend on the part of networks toward bringing the TV viewer ever deeper "inside the game." Besides the miking of players, coaches, umps and, soon, team owners, mascots, scouts, groundskeepers, and the toilet where Big Papi takes his ceremonial pregame dump, these "inside the game" ploys include among many other annoyances the sound-and-fury-signifying-nothing use of current players as analysts (e.g., Eric Byrnes), the loathsome, game-action obstructing in-game dugout managerial interview, and the on-scene misinformational stylings of rictus-grin Ken "The Rockies beat the Cubs in Round 1" Rosenthal. None of it pulls me further into the game. Luckily the game can't be so easily autopsied by the brutish invisible corporate hands at the controls. Its beauty and joy and drama survive. Still, sometimes I wish I could return to a time when I didn't know that meetings at the mound between pitching coaches and beleagured, unraveling pitchers resembled a one-on-one pep talk between a sales manager and an underperforming salesman in a conference room on the second floor of a nondescript building out by the Ikea and the Chilis on Route 73. The truth is I was never farther inside the game than when I had to imagine almost everything about it, when all I had were these cards and a few stats and an occasional soberly announced game on TV. And names. I had names. Sometimes they worked on me like a magic spell. I went inside the game saying Bob Apodaca . . . Biff Pocoroba. Bob Apodaca . . . Biff Pocoroba. Bob Apodaca . . . Biff Pocoroba. Anyway, lineups for tonight's game (FOX, 6:35 MT): Red Sox Carl Yastrzemski, 1977

2007-10-26 08:47

The Yazmobile Chapter 2 (continued from Carl Yastrzemski, 1975) i. I’ve never asked God to show me a sign, but when I was a kid I wrote a letter to Yaz. “Dear Mr. Yastrzemski,” I wrote. I may have used this 1977 baseball card to get the spelling right. I told him the Red Sox were my favorite team and he was my favorite player, then I asked him for his autograph. I sealed and stamped the letter and took it out to our aluminum mailbox, flipping the red metal flag up to signal to the mailman that there was an outgoing letter. Later in the day, when I saw that the flag was back down, evidence that the mailman had made his daily visit in the four-wheel-drive Subaru required for rural Vermont postal delivery, I felt like gravity had loosened its hold just a little. My letter was on its way to Yaz! In a certain way my real life began that day, my life in the world. To that point I had never wanted anything beyond what was close at hand, beyond my family, my home. I began waiting for something more. Weeks went by, months, years. ii. I spent the summer of 1987 in California, farther from the Red Sox than I’d ever been. My brother met me out there at the end of the summer, and the plan was that he and his friend Dave and I would drive all the way back east together. Actually, I had not yet learned how to drive and was hoping (and dreading) that I’d get a chance to practice as we Kerouacked ecstatically across the vast continent. I’d been in driver’s ed at boarding school in 1985, but I’d gotten expelled from the school before completing the course. I probably wouldn’t have passed the course anyway; I was an awful driver from the start, profoundly tense and unfocused, capable of provoking a beady-eyed expression of fear on my instructor’s face even when we were inching down remote dirt roads. After the expulsion, I'd shied away from any chances to learn to drive. Though I was more comfortable being a passenger, and still am, I lived in fear that my inability to drive would turn out to be a tragic flaw, that I’d be called on to drive a guy having a massive coronary to the emergency room, and the last words he’d have to hear would be my apologies for never learning to drive a stick. I was hoping that somehow on the long drive across the country I’d free myself of all my limitations; somehow I’d no longer be myself, but someone better. The car was an Audi that my brother and Dave had arranged to drive east for a relocating businessman, and it broke down before we even got out of California, on a long uphill part of the highway just outside Truckee. We’d detoured to a Grateful Dead show the night before (obviously something not mentioned in the agreement signed by the businessman) and had during an acid trip bought three buds of peyote from some guy. I think we were probably hoping to try the peyote in a spectacular locale on our drive home, the Rocky Mountains, the Grand Canyon. Instead we ate them in a cramped hotel room in Truckee as we waited for the Audi to be repaired. They tasted so awful that we had to crush them up and shove them into ham sandwiches and wash each hideous bite down with several chugs from our stash of Budweiser tall boys. Once we finally choked them down we began to wait. During the acid trip the night before we’d passed the peyote buds around and agreed that they seemed to be pulsing and glowing in our palms. Now in the hotel room we thought about that glowing pulse, now presumably inside us, and we waited for the inevitable moment of liftoff. We waited to soar to other worlds. We’d find out the next day that the engine of the Audi was damaged beyond repair, causing us to abandon our cross-country drive and fly home. By then we’d have realized the peyote was bogus. But that night with the repulsive taste of it burning through the cheap beer on our tongues we sat in that hotel room and stared at one another, giggling, waiting to see the face of God. (to be continued) Carl Yastrzemski, 1975

2007-10-24 10:56

The Yazmobile Chapter 1 My earliest memory is of chasing after my brother, a toy machine gun in my hands. I wanted to be part of the war game he was playing with his friend Jimmy, but he and Jimmy were too big for me, their legs too long. I couldn't keep up. Some time around then, my brother began serving as my interpreter. I could make sounds, but no one could understand them as words except my brother, who passed along my wishes to the grown-ups. This arrangement didn't last that long, but in a way his role as my conduit to the world lasted for many years, stretching into adulthood. We drifted through our twenties together, sharing one small Brooklyn apartment after another, trying to salve the various disappointments of our lives by using the language we'd shared since before I'd even fully known how to speak. The gaps between us grew, our lives inevitably continuing to diverge even as we remained under the same roof, the clutter of our directionless lives entangled. But we always had at least one way to connect, a shared language that had been there for most of our lives, the center of that language the prayer-word Yaz. The card above is from 1975, the year the shared language got its center. I was seven and my brother was nine. It was our first full year living in Vermont, away from our father, away from the sidewalks and toy machine guns of New Jersey. I’d never paid any attention to baseball before, but suddenly my brother was playing little league and collecting baseball cards, and what he did, I did. This imitative way of being was something that would in many ways define my life, my imitations often going beyond mimicry to become a kind of inward orthodoxy that seized on one or another of the various pursuits of my brother as if they were the exploits of a visionary, each detail worthy of the impassioned scrutiny of a solitary monk. I understand my connection to baseball in this way. My brother liked baseball a lot. In fact, he was a better player than me, bigger and stronger, even able by age 13 to throw a curveball. But I don’t think he grabbed hold of its details as fiercely as I did, something I noticed early on, when we were both still in little league and he tried to argue that Rogers Hornsby, and not Ty Cobb, held the record for highest lifetime batting average. It may have been the first time in my life that I knew more than my brother about something, ironic given that I studied the baseball encyclopedia so assiduously because I subconsciously believed it would bring me closer to my brother. I had trouble when he went away to boarding school for his junior and senior years. Who was I supposed to be now? When he came back for visits we would stay up late talking, lying on our beds in the dark. He did most of the talking, telling me about the kids in his dorm. True to form, I built these friends of his into the larger than life figures of myth. When I visited him for a weekend at the school and met some of the friends he’d spoken of all I could do was laugh uncontrollably, hysterically, even the most mundane utterance from their mouths seeming to me to be the funniest thing I’d ever heard. Even at the time I realized that I was laughing in large part out of terror. Who was I to be in the presence of these impossibly sophisticated, hilarious gods? After my brother graduated from the boarding school I followed him there, per the mimicking script of my life. The terror of my earlier visit persisted throughout most of my truncated stay at the school, but it was certainly at its worst in my earliest days there. One bright and sunny Sunday a few weeks in I slipped into the TV room on the first floor of my dorm. The TV room was not a cool place to be, especially on a bright and sunny Sunday when you could be out talking and laughing in your Izod shirt with a gaggle of beautiful girls in front of a leaf-pile, your lacrosse stick perched on your shoulder. My other stints in the TV room thus far had been sad, shame-filled congregations with other dateless and misshapen fellows to watch Michael Jackson and Prince prance around on Friday Night Videos while all the regular kids groped one another through L.L. Bean garments under the soft, English Literature-enhanced boarding school stars. But on this particular Sunday I had no company at all. It was just me and the television, and as I kept my eyes locked on the screen I could occasionally hear people on their way out to join the laughing sounds of autumn, the passers-by probably wondering why the weird kid who looked exactly like his more normal brother was subjecting himself to the unprecedented indignity of watching television during the daytime. But I guess to my credit, at least in this one instance, I didn’t really care what anyone thought. I had to watch television on this particular Sunday, for it was October 2, 1983. It was Carl Yastrzemski’s last game. Come on Yaz, I said whenever he came up to bat. I probably meant to say it to myself but I’m sure as the game went on and he kept failing to homer and thus match the renowned adieu of the man who had always cast a shadow over his career, Ted Williams, my little prayer began to sneak out of my mouth, no doubt prompting the more well-adjusted kids ambling by to note that now the weird kid was talking to himself. By his last at-bat I was pleading out loud to the television, my cracking voice slapping off the concrete TV room walls. It seemed like something I had been doing all my life: pleading for Yaz. He settled into his familiar stance, twirling his bat forward and leaning toward the pitcher slightly, as if trying to hear the pitcher's internal monologue. The TV thinned the crowd noise to a hollow buzz, but I could still tell that they were all shouting the same syllable as I, everyone wasting the last of their voices on that yawing, fizzling, incantatory sound. "Come on, Yaz!" I hollered. "Come on, Yaz!" (to be continued) Clint Hurdle

2007-10-23 12:15

I haven't yet quite figured out how to deal with disappointment. Though I can't really complain (I'm relatively healthy and have people to love, plus the team I routinely disappear into has made it to the World Series, so like any junkie in possession of good shit I really don't care about anything else right now), I'd have to say my adult life has been characterized by some disappointment. Certainly no one ever thought I was going to be the next Mickey Mantle of anything, and on one level I didn't ever really believe I'd amount to much either, but in the daydreamy realm where I have spent much of my life I believed that at some point I'd be writing and publishing novels, that I'd find a way to give back to the world the kinds of books that have kept me going as I stumble and nap and cringe through the days and weeks and years. It's disappointing to me that this hasn't happened, and I'm not that young anymore, definitely not young enough to ever be considered promising, so some days I wonder if I'm just swinging at pitches I can't possibly hit. Clint Hurdle, like all athletes, must have come to a point in his career when he asked himself this question. It must have been a difficult question, especially for someone who was supposed to have creamed those pitches but who except for a few sweet days never did. Indians-Red Sox Game 7 Chat (updated with lineups)

2007-10-21 07:10

I’d be happy if either one of these able fellows could somehow take the mound tonight on full rest (Beckett does indeed appear ready to pitch in relief), but they wouldn’t be my first choice if I could reach back into history for anyone. They’d have a lot of good company among the pitchers passed over for the job, including: Cy Young. The winner of all imagined conversations in pitching heaven, e.g.: "Wow, that is a lot of Cy Young awards you’ve got there. No doubt about it. Hm? What’s that? What’s my name? Why don’t you ask one of your little trophies. You know, on your way to getting your shinebox." Smokey Joe Wood. His 1912 season was one of the greatest ever. Also the possessor of the coolest name for a pitcher ever, with the possible exception of Blue Moon Odom. Incidentally, he is a member of the all-time team of Red Sox-Indians; after arm trouble killed his pitching career he made a comeback as a part-time outfielder with the Cleveland Indians, helping them win the 1920 World Series. Babe Ruth. Really tough not to pick the Babe, who for many years held the record for most consecutive shutout innings in World Series play; plus, of course, he could bat and let the DH David Ortiz hit for Julio Lugo (by the way, has the DH ever been used for anybody but the pitcher?) Roger Clemens. The numbers in context point to him as quite possibly the author of the greatest regular season pitching career of all time, and if he were on the mound tonight for the Red Sox, in his prime, I wouldn’t complain, but I’d also be a little worried about an overpumped bat-throwing ump-berating meltdown. Pedro Martinez. The dominant, fearless maestro. When Clemens was at his peak for the Red Sox I was gratefully aware that we had one of the best pitchers in the game; when Pedro was at his peak for the Red Sox I often found myself wondering if we had the best pitcher who ever lived. But if I could pick one player from Red Sox history to pitch tonight’s game, I’d follow the thinking of former Red Sox manager Darrell Johnson, who once said, "If a man put a gun to my head and said I’m going to pull the trigger if you lose this game, I’d want Luis Tiant to pitch that game." Luis Tiant came through in many a big game for the Red Sox, and I believe he should be in the Hall of Fame. But those are not the sole reasons for my choice. Part of the reason has to do with the element of resurrection in his career. After breaking in with the Cleveland Indians, where he authored a season for the ages in 1968, Tiant appeared done as a pitcher in the early 1970s. These terse lines from the transaction section of his page on Baseball Reference.com tell the story: March 31, 1971: Released by the Minnesota Twins. Picked up, dumped, picked up again, dumped again. The Red Sox took a chance on him and to their credit stuck with him throughout 1971 as he compiled a putrid 1 and 7 record. The following season he turned things around, and for most of the rest of the decade he was once again among the best pitchers on the globe. He had been finished, a Hefty bag left on the curb, but he came all the way back, resurrected. But the theme of resurrection isn’t, in the end, the deciding factor for me, though it feeds into it. Here’s the main reason I’d give the ball to Luis Tiant: Joy. Luis Tiant not only dominated in big games, he entertained, he enchanted, he enthralled. He toyed with batters with his wide assortment of bedeviling pitches and his looping corkscrew windup (the most imitated big league gyration of my childhood), and in doing so and by the sheer magnetism of his ebullient personality he played the entire packed house at Fenway like it was the world’s biggest and loudest musical instrument, a thumping, chanting, cheering organ of hope and celebration. If you’re going to play a game seven, you might as well win, and if you’re going to win, you might as well enjoy it. So here's hoping that the spirit of El Tiante can somehow flow into the corkscrew windup and the wide assortment of pitches of the actual starting pitcher for tonight's game, Daisuke Matsuzaka, whose season to date has been a little like the first two acts of Luis Tiant's career, great promise followed by a seemingly unstoppable demise. Here's hoping that now is the perfect time for Act Three. * * * The lineups (courtesy of Amelie Benjamin's Boson Globe blog): Indians 1. Grady Sizemore, CF SP - Jake Westbrook Red Sox 1. Dustin Pedroia, 2B SP - Daisuke Matsuzaka Larry Andersen/Indians-Red Sox Game 6 Chat

2007-10-20 14:37

Who is the most famous middle reliever ever? For the entirety of baseball history this has been an unanswerable question, for no middle reliever has ever really attained any kind of fame whatsoever. Middle relievers ride unrecognized on the Green Line to Fenway Park, slump in the shadows during the cheers of starting lineup introductions, and, even if they manage to get into a game, are already in the showers by any climactic moments of victory. By contrast, their pine-riding brethren in the dugout, non-starting positional players, such as Bernie Carbo, occasionally have moments of great renown. Middle relief, like the bulk of life, doesn't really lend itself to special moments. In recent years especially it has become abundantly clear that winning a World Series requires strong middle relief work, yet no middle reliever has ever won a postseason award (or a regular season award, for that matter). This could all change today, if the team featured in this preposterously titled Future Stars card from 1980 manages to close out the Boston Red Sox in Game 6 of the American League Championship Series (FOX, 8:23 ET): the Indians' best and most important player so far has been middle reliever Rafael Betancourt. By contrast, the Red Sox' middle relievers have been frighteningly shaky. This disparity in the area of middle relief does not bode well for the Red Sox, especially considering that their starting pitcher for today seems no longer capable of going deep into a game against a top-notch lineup like the Indians. That bullpen door is going to swing open at some point today and Red Sox fans are going to wish they'd spent more time praying to the underappreciated gods of middle relief. Here are three of those gods, Future Stars that foretell of a future that will never escape the abundant limitations of the present. None of the men are that young, each with several seasons in the minors under their belt. One, Bobby Cuellar, had surfaced in the majors three years earlier but would never surface again. Another, Sandy Wihtol, would briefly seem the most successful of the three, appearing in 17 games in 1980 while his fellow Future Stars continued riding minor league buses, but Wihtol would be back in the minors the following year. The third Future Star, Larry Andersen, after seeming at first to be bound for the same oblivion as his cohorts, instead caught that long, steady wave that middle relievers sometimes catch, their major league careers stretching on and on for one franchise after another, their longevity finally imprinting some awareness of their name of the minds of casual fans, who are always surprised when these riders of the long, steady wave, who they thought had been jettisoned from the majors years ago, appear in a game. Larry Andersen's renown has increased beyond that of the usual long-tenured itinerant middle reliever, mainly because the Boston Red Sox once acquired him for the stretch run by trading away a minor league first baseman who had yet to show any signs of being able to hit for power. Since the Red Sox had another minor league first baseman, Mo Vaughn, who had shown ample signs of being able to hold down the middle of a lineup, it didn't seem like a bad gamble to trade Jeff Bagwell away. Many jokes have been made about the trade, some of them by the witty Andersen himself, but the truth is, as a Red Sox fan, if I could have just one of the two players in their prime on my team for today's game, based on the relative strengths and (glaring) weaknesses of the 2007 team, I'd pick Larry Andersen over Bagwell. I'd pick the middle reliever. Bernie Carbo/Red Sox-Indians Game 5 Chat

2007-10-18 14:34

Summers are never the same once your days as a student come to an end, so in a way my last real summer came in 1990, just after I graduated from college. That last summer ended with a thin rice-paper letter from China. I’d been planning to return to Shanghai to teach and to live with the young woman I’d fallen in love with during a recent semester abroad, but the letter from the woman let me know I’d have to make other plans. She'd met another guy. I’d been working on the college campus maintenance crew to save up money for a ticket to China, and when I got the fractured-English Dear John letter I used the money to meander around Europe instead. The Red Sox were battling for a playoff berth as I left, and the first time I bought a Herald-Tribune to check on them I read about Tom Brunansky extending summer a little longer by making a spectacular game-winning, division-clinching catch in the very last moment of the regular season. The magic-wand catch made me wonder if this was going to be the year when summer finally lived forever for the Red Sox. But by the second time I checked a Herald-Tribune, which seems in my memory to have been the next day, but which must have been at least a few days later, the Red Sox had already been dumped from the playoffs by the Oakland A’s. Summer was gone for good, and all I could do was wander around until the money ran out. Another summer may soon be over for the Red Sox, but you never know. They've been in worse spots. In 1975, for example, the Red Sox trailed the Cincinnati Reds three games to two and were losing by three runs with two outs in the 8th inning when the man pictured here was sent in to pinch hit. He fell behind in the count, barely fouled off a pitch to stay alive, then drilled a three-run home run over the centerfield fence. Summer was back. Not only that, Carbo ensured that the summer of 1975 was one of those rare seasons that would live forever; as Boston's native son Jonathan Richman might have put it: "That summer feeling's gonna haunt you the rest of your life." No telling if there's any summer feeling left in the 2007 Red Sox. But they've been told in other years that summer was over and have refused to listen. Even some of the players who weren't around in 2004 have experience turning sure fall back into summer, chief among those being relative newcomer Josh Beckett, tonight's starting pitcher, who started the Marlins improbable comeback in the 2003 NLCS by beating the Cubs with his team down three games to one, just like his team is tonight (Game 5 set to start at 8:21 ET on FOX). Though the Indians seem to want to obscure that memory of Beckett's with a memory more redolent of endings tonight (they have hired Beckett's ex-girlfriend as their National Anthem singer), I'm hoping Beckett has one more day of sizzling summer in his right arm. Joe Niekro/Red Sox-Indians Game 4 Chat

2007-10-16 11:41

Life is a knuckleball, a jagged, ridiculous path with no guarantees. Maybe things will work out OK, maybe things will work out horribly, but most likely they'll be a mixture of the two, your beleaguered catcher unable to handle strike three, which will bound to the backstop and allow mounting adversity another baserunner and more chances to whale on the knucklers that don't knuckle. And there will be plenty of knucklers that don't knuckle. But though the ability to throw good knuckleballs seems to come and go almost without reason, there is also something about knuckleballs, and about life, that gives a late-blooming nobody such as myself hope. Consider Joe Niekro, seen here with a pensive look altogether appropriate for a 33-year-old 10-year veteran with a losing lifetime record. Perhaps Joe Niekro is wondering if the end is near. In fact, Joe Niekro at the time of this 1978 card was attempting to reinvent himself from a mediocre fastball-curveball pitcher to a pitcher who could, like his older brother Phil, rely on the most unreliable phenomenon in the baseball world, the knuckleball. And Joe Niekro did end up mastering the pitch as few others have, going on to win 221 major league games, most of them coming after the time when most major league pitchers have traded in their baseball cleats for golf shoes. The knuckleball offers the possibility of redemption. Consider Tim Wakefield, who starts for the Boston Red Sox in Game 4 of the A.L. Championship Series tonight (8:07 ET, FOX). Wakefield was a washed-up light-hitting minor league first baseman when he first decided his path to the majors was going to have to follow the flight of the knuckleball. He made it to the majors at age 25, hardly a phenom, but pitched brilliantly in his rookie season to help the Pittsburgh Pirates win their division. The knucklegods abandoned him the following season, and in the season after that he pitched poorly again, this time in Triple A. In the offseason he sought the help of Phil and Joe Niekro, and by 1995 he was back in the majors, pitching well for the Boston Red Sox. Though he has been for some time the longest-tenured current player on the Red Sox, and by all accounts a steadying clubhouse influence and a beloved pillar of the community, his fortunes have continued to rise and fall as if tied to the transitory, unpredictable qualities of the pitch he relies on. One month he is unhittable, the next the sweating maestro of wild pitches and beachball lobs, the next a maddening combination of the two. Even in his worst moments, as in the 2003 playoffs when an unknuckling knuckler was Bucky-Dented by Aaron Boone over the left field fence to eliminate the Red Sox, Wakefield is never far from his best (before that pitch Wakefield had been so brilliant that if the Red Sox had hung on to win he probably would have won the series MVP); and even at his best, such as his fearless and stupendous 3 frames of extra-inning shutout ball to win Game 5 of the 2004 ALCS against the Yankees, he is never far from hideous disaster, his pitches moving so much in that game that the Yankees nearly grabbed a lead on the following "rally":

And so now, as they have so often in recent seasons, the fortunes of the Boston Red Sox rest on that metaphor for the transitory and uncontrollable nature of life itself, the knuckleball. I'll be wearing my treasured Tim Wakefield T-shirt and praying. And probably also drinking fairly heavily. What's the difference?

2007-10-16 04:52

Welcome to the Red Sox-Indians Game 3 Chat, Broham

2007-10-15 14:56

As it was, Brohamer came and went without leaving much of a trace. He played for a few years in Cleveland, his only departure from anonimity coming in his role as the unwitting Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the 10-Cent Beer Night riot (as mentioned previously on Cardboard Gods, Len Randle's hard slide into Brohamer at second base in Texas led to a beaning of Randle, which led to a fight and the pelting of Indians players by Texas fans, which led to a night for the ages on the Rangers' next trip to Cleveland). He went on to play two years for the White Sox, the most stunning legacy from that era the fact that in 1976 Brohamer was intentionally walked 9 times (the player who most often followed him in the lineup was named Bucky Dent), then played for the Boston Red Sox for a couple years before returning to Cleveland for one more brief and inconsequential go-round. The closest he ever got to the playoffs was when he started at third base for the Red Sox in the 1978 one-game divisional play-in game against the Yankees. Brohamer had been having an excellent season as a part-time player for most of the year, his batting average over .300 as late as July 9, then after a slump climbing back to .270 by August 28, when the Red Sox held a 7½-game lead over the second-place Yankees. From that point on, however, Brohamer, forced into playing nearly every day by injuries to second baseman Jerry Remy and third baseman Butch Hobson, collected just 10 hits in 69 at bats for a sickly .145 batting average. But nobody blames Jack Brohamer for the collapse. In some ways I've always aspired to this level of culpability in my life. I don't want to be held responsible. I don't want anyone cursing my name. Better to just stick to the sidelines, the shadows, and let someone else get the glory or take the fall. Better to just Brohamer it. Meanwhile, I live vicariously through game-playing strangers, drawing as close as possible to them in my imagination in their times of triumph, and distancing them as much as possible from me with curses and even hatred when they stumble. With that in mind, here are the lineups for today's Game Three of the deadlocked American League Championship Series (7:10 ET, FOX), courtesy of Ameile Benjamin's Boston Globe blog: Red Sox SP - Daisuke Matsuzaka Indians SP - Jake Westbrook Rick Wise/Indians-Red Sox Game 2 Chat

2007-10-13 15:23

Here is a portrait of a man on the brink of oblivion. Like all great art, this piece expands the conventional bounds of its genre, transcending the strictly figurative representation that was the function of late twentieth century baseball card portraiture with both the abstract wash of colors in the background and the apparent slight but jarring distortion of the body in the foreground. The figure, "Wise," seems to have unusually long legs and wide hips in relation to the short torso and short arms, this distortion of the human form a seeming allusion to the powerful-legged, spindly-armed Tyrannosaurus Rex, which in turn gives the portrait overtones of great, fearsome power nullified by the certainty of extinction. This theme of extinction is furthered in the blurring in the background of what viewers at the time of the artwork would understand contextually to be the crowd, a gathering assembled for the purpose of cheering for and cursing and exalting and even in a crude way praying for and thus making sacred game-playing participants such as the one pictured here, "Wise." The blurring of all faces in the crowd, coupled with the look of apprehension on the face of Wise and the aforementioned anatomical distortion of his features, creates a sense of ending, of things once solid melting into air. No faces can be seen in the crowd, only here and there among the shapeless colors small soft-edged spheres, the motif perhaps an attempt on the part of the artist to contradict the allusions to the famous quote above with intimations of an afterlife, as if the orbs were souls able to carry something of the individual beyond the inevitable cessation of earthly life, of flesh. Less ambiguous than the mysterious orbs is the fate of the central figure, Wise, whose allegorical name in this context, coupled with his obvious inability to cease the dissipation of the crowd (and, by extension, the dissipation of meaning, for what is a game with no crowd?) seems to offer a bracing commentary on the limitations of the rational mind, of human wisdom. There will come a moment when all we know won’t mean anything. Wise seems to be verging on this moment. He is either looking around to see if there is anywhere where things are still solid or he is looking back, trying to find a place and time he can cling to, something that will never melt into air. If he is looking back, what is the object of his gaze? What can we cling to in our last moment? The portrait offers no clue, but on the back of this card (where artisans who created these works supplemented the portraits on the front of the cards with intricate numerology and text), there is a cartoon of a ballplayer without thick glasses and with a broad smile (free of limitations and sadness), looking at a scoreboard that tells the tale of a victory. Above the cartoon is the following line of text, which according to experts in the interpretation of the back of the card numerology is exceedingly far-fetched, the stuff of a fairy tale, suggesting that all we have in the end are fairy tales, slim, brilliant moments that are too good to ever have been true: "Rick hurled no-hitter for Phillies vs. Reds, 6-23-71, and hit 2 homers in the game." Indians-Red Sox Game 1 Chat

2007-10-12 07:14

Game time is still quite a ways away (7:07 ET, FOX), but I couldn't sleep much last night and now I'm up and all I can think about are Indians. One of the first things I saw this morning after not sleeping was an article in the Boston Globe entitled "They've had some chief concerns," in which Dan Shaughnessy wonders what Jacoby Ellsbury thinks of Chief Wahoo. It might be an interesting follow-up to readers of yesterday's interview with historian Akim Reinhardt. A high point for me is when the customarily pompous and oblivious Shaughnessy seems to dismiss all cultural controversies over sports team names by concluding a listing of some of the controversies with the declaration, "For all I know, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen are offended by the Minnesota Twins." Anyway, here's Chief Wahoo himself riding on the shoulder of the Eck, shown here in the first of his many lives in major league baseball (those lives being, in order, young flamethrower for the lackluster Indians, ace and would-be savior of the powerful but pitching-desparate Red Sox, washed-up meatballer for the Cubs, Hall of Fame-caliber bullpen ace of the A's, and, finally, journeyman reliever-for-hire). On the back of this card I see that he played his first season of pro ball in Reno at the age of 17. The following year, also in Reno, he struck out over 200 batters, and by the age of 20 was in the major leagues. In this photo he is 21 or maybe 22, and he already has 26 big league wins and is months away from pitching a no-hitter. His storied early success with the Indians makes his trade to the Red Sox seem, in retrospect, a bit like the more recent coming of Josh Beckett to Boston. In Eck's first season with the Red Sox, 1978, he seemed to be the final huge piece of the World Series Championship puzzle, the brilliant young ace they needed to complement their aging resident Big Game Pitcher (in this analogy, Beckett is Eck and Curt Schilling is Luis Tiant). In the end Eckersley's worthy efforts--he won 20 games in 1978--were not quite enough to win the division for the Red Sox, who fell in a one-game playoff to the Yankees, just as they had 30 years earlier in a one-game playoff against, who else, the Indians. That year the Indians went on to beat their partners in questionable baseball team names, the Braves, in the World Series, their last such triumph. They came close in the 1990s but always seemed to lack that dominating ace, their hitting-rich teams resembling the pre-Eck Red Sox of the 1970s. Now they have not one but two aces every bit as good as Eck ever was or Josh Beckett is, C.C. Sabathia and Fausto Carmona. The Red Sox, on the other hand, have, after Beckett, an old man who has lost his fastball, a knuckleballer with a bad back, and a rookie from Japan who seems to have run out of gas months ago. It's no wonder I couldn't sleep much last night. The Cardboard Conversation, vol. 1

2007-10-11 04:46

The truth is, as my beloved Boston Red Sox prepare for what is shaping up to be a brutally tough fight in the American League Championship series, I’ve been thinking about little else besides Indians. So I decided to call on an expert. In the following interview, the first edition of the Cardboard Conversation, I ask Akim Reinhardt, author of the critically acclaimed study of the political history of the Lakota reservation, Ruling Pine Ridge, about Yankees, Indians, and the possible spiritual implications of a plague of midges. The Bronx-born Reinhardt, currently associate professor of history at Towson University, grew up playing little league baseball in Van Cortlandt Park and going to Yankees games with his father. He has absolutely no recollection of Gene Locklear. Cardboard Gods: Can you describe the most memorable game you attended at Yankee Stadium as a child? Akim Reinhardt: It was such an impression that I tried to write a short story based on the event when I was in high school, but it never panned out. Might as well dish it here. One day my dad showed up at the little league game in the Fall of 1977, which was unusual because he worked a lot of Saturday mornings back then, running his own business as a general contractor. And then out of the blue, after the game, he tells me and my best friend Dirk that he’s taking us to the Stadium. It was the second to last game of the year and they were playing the Tigers on Fan Appreciation day. We all got a big, plastic coffee mug with a team photo wrapped around it, encased in clear plastic. We sat up in the nosebleeds and near us some dirtbag (tix were cheap enough for dirtbags to go to games back then) was pounding beers out of his free coffee mug. In retrospect, it makes a lot more sense than the paper cups they gave you; there were no plastic bottles back then. Well, there was a rain delay, lasted over an hour I think, and two memorable things happened. First, me and Dirk went down to the empty front row seats behind the Yankees first base dugout. We were awed by it. Neither of us had ever been so close and taken in such a view of a major league park before, much less The Stadium. We slid over to the outfield side of the dugout and I was cautiously leaning over the fence, reaching to touch the sacred dirt when I heard furious angry mumbling to my right. It was the same dirtbag from the upper deck, still clutching his free mug, still quaffing liberally, and now talking under his breath: "Fuck them! Fuckers. Fuck it, I’m gonna do it. Fuck it!" He knocked back the last of his beer, flung the mug to the side, hopped over the fence, and ran across the field. Out of nowhere, several security guards emerged and honed in on him. Everyone converged somewhere around the pitcher’s mound and three guys hit him simultaneously from three different angles, driving their shoulders into him, like Jack Lambert, Jack Ham, and L.C. Greenwood all finding the QB at the same time on a blitz. It was short and ugly. The guy was crumpled up like Beetle Bailey after the Sarge gets pissed at him. Me and Dirk were so shocked, we just stared a bit and then scooted away for fear of the violence and law breaking somehow rubbing off on us by proximity. The second memorable event from that game was near the end of the rain delay, Dirk and I walking through the bowels of the stadium and it came on the P.A. system: Boston had just lost, to Cleveland I think [editor’s note: the 8-7 Red Sox loss--to Baltimore--was described recently on Cardboard Gods by Jon Daly]. It was official: The Yankees had won the division. Dirk, a Boston Red Sox fan, had turned 9 six weeks earlier. I was 6 weeks away. He turned to me solemnly, extended his hand, and congratulated me. I did have Munson’s 1976 card on my wall for a while. If memory serves, it had a red banner at the bottom which said All Star. The Munson baseball card is long gone, but I still have a matted poster of Munson on the back door of my old room in my mom’s place. It’s about the only thing left in the room from my childhood. A.R.: It was after college. I went to Michigan, studied East Asian History, and bombed. I graduated with under a 2.5, but did manage to get out in four years despite having read virtually nothing and taking no notes. I didn’t skip classes though; I’d go to each one and listen intently, unless the prof. was boring, in which case I’d write poetry. After Michigan I kicked around for a few years. Without professors telling me what to read, I just started reading on my own. I came across a couple of Chestnuts about the Plains Indian Wars of the mid 19th century: Ralph Andrist’s The Long Death and Dee Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, neither of which are very good from a scholarly point of view, but quite readable. Brown’s was actually a bestseller in the early ’70s but leans heavily on Andrist's work. But the book that really did it for me was Vine Deloria’s Custer Died For Your Sins. That book holds up well. It’s still a classic, and Deloria’s one of the true pioneers of modern Native American Studies. A few years later I moved back to New York and got my Master’s at Hunter College. By that time I knew what I wanted to do. But another thing to keep in mind is this. Baseball is no longer the sport of the poor. Once upon a time, MLB players were mostly the children of immigrants, tenant farmers, and other hardworking poor people. It offered modest pay and little respectability, but was an easy choice over jobs like coal mining, sharecropping, and factory work, even if you did have to pick up an extra job during the offseason. More recently, however, it is the domain of white suburbanites, both on the field and in the stands. Major League players often grow up in suburbs that have the land and resources to build local diamonds in public parks as well as schools. Latin America of course has countless poor kids scrapping their way up the minor league chain, but most white American players are middle class suburbanites, and blacks have almost completely abandoned baseball altogether in favor of football and basketball. Unfortunately, Indigenous people are still near the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder in this country; it’s not a cause, but there is a strong correlation. But in reference to the above question, Native peoples are beginning to see improvements in their economic situation, slowly but surely. Whether that will translate into more baseball players, it’s hard to say. Though it’s probably worth noting that Chamberlain grew up not on the rez, but in Lincoln, Nebraska, ironically while I was there getting my Ph.D. And Lincoln is a typical, modern American town with a suburban settlement pattern and lots of diamonds. I played a ton of city league softball on public parks when I was there, Summer and Fall. Some Summers we had two different teams going, with basically the same players. C.G.: Why is the economic situation in the reservations so problematic, and is that all changing with gambling? C.G.: Can you offer any thoughts on what kind of hurdles a talented Native American athlete such as Ellsbury and Chamberlain might have to face in an attempt to rise to the major leagues? I don't think we currently live in a time where baseball coaches and front office people will put up any hurdles, though I do have my theories about why there are so few Black pitchers as opposed to Black position players, but that's probably for a different blog entry. White Sox, 1977

2007-10-09 10:52

I grew up in the 1970s, the age of embarrassment. In the early years of the decade the president was revealed as a paranoid criminal. He quit, disgraced, and was replaced by a guy known for being ineffectual and tripping over things. This second guy soon got voted out of office in favor of a peanut farmer who revealed more than anyone wanted to know in an interview in Playboy, admitting he had "lust in his heart." Later, in a nationally-televised speech, he described America’s "erosion of confidence"; in the embarrassingly frank president’s estimation the whole country by the end of the 1970s was demoralized and ashamed, as if it had somehow channeled from sea to shining sea the cringe-shouldered stoop of an awkward acned bespectacled teenager who spent his free time playing solitaire Strat-O-Matic and masturbating. It’s fitting that this infamously depressing "malaise" speech by President Jimmy Carter on July 15, 1979, came just three nights after Disco Demolition Night, just as it’s fitting that Disco Demolition Night occurred in the same place where, three years earlier, several of the gentlemen pictured here played a major league baseball game while wearing shorts, an event that, until the time when a major league baseball team takes the field wearing flowery sleeveless summer dresses and heels, will stand as the single most embarrassing uniform-related moment in baseball history. Though embarrassment was everywhere in the 1970s, it may have crested on August 8, 1976, when the White Sox plied their trade in front of their competitors, the media, and 15,997 paying customers while dressed in what must have felt for all the world exactly like it feels in a dream when you realize you’ve left the house after forgetting to put on your pants. Incredibly, the White Sox won that game. They did not win many others that year and did not ever wear the shorts again, except, curiously, for this portrait for their 1977 team card. I’m not sure why they did this, but whoever made it happen deserves a medal. The whole team deserves a medal, in fact, for they and whoever had the idea for the pose in the first place are embodying the greatest aspect of the 1970s, one that goes hand in hand with its designation as the age of embarrassment: no matter what might come your way, embrace it. If you find yourself out in the middle of the action dressed in a shirt with a preposterously huge collar and your afro bulging like Mickey Mouse ears out from under your cap and your touchingly vulnerable knees as visible as those of a skirt-wearing member of the flag squad, embrace it. You only go around once, and most of that once is monotony and sameness, so you might as well celebrate the glorious mistakes. Red Sox-Angels Game 3 Chat

2007-10-07 08:56

A little over a year after his legendary career as a California high school athlete concluded, Ken Brett became the youngest pitcher ever to appear in a World Series, posting 1.1 scoreless innings for the Boston Red Sox in the 1967 fall classic against the St. Louis Cardinals. The 1966 number 1 draft pick of the Red Sox could throw hard, run fast, and hit as well or better than many major league position players, plus by all accounts he was unflappable, oblivious to the pressure of the big moment. My guess is that in 1967 the future seemed very bright for the 19-year-old Ken Brett. As it turned out his Hall of Fame destiny fell to his less ballyhooed younger brother, George, a 1971 second-round draft pick of the Royals. As George played his entire career for one team, Ken roamed from city to city, leaving the Red Sox after four partial seasons to play with the Brewers for one season, the Phillies for one season, the Pirates for two seasons, the Yankees for two games, the White Sox for most of one season and part of a second, the Angels for a season and a half, the Twins for nine games, the Dodgers for thirty games, and finally two seasons as a seldom-used reliever on his younger brother's squad in Kansas City. This morning I balanced the shock of learning that Ken Brett is dead (he passed away of brain cancer in 2003) with the image of him in his first appearance as a teammate of his brother, who recalls in a 2003 Spokesman Review article by John Blanchette that Ken, to entertain George and their good friend, Royals catcher Jamie Quirk, sprinted in from the bullpen like a kid making believe he was an airplane, slaloming through the outfield with his arms straight out at his sides. This makes me happy, as it seems to suggest that Ken Brett was not bitter that the golden path he seemed born to walk down turned into a series of potholed roads, the purposeless route of a journeyman. If we're lucky, if we're loved, we get the idea as children that life will be a golden path. But maybe if we're even luckier we're able to keep laughing when the path gets complicated. So far in the 2007 playoffs the path has been golden for the first of Ken Brett's ten teams, and it's tempting to think that it will continue to be so as the series resumes this afternoon in California (TBS, 12:07 PT). But you never really know what's going to happen. The best you can do is follow the lead of Ken Brett. Whether it was a World Series game in 1967 that seemed to foretell a long career of glory or a late season mopup appearance in a 1980 blowout loss that signalled the end of a career of nondescript drifting, Ken Brett enjoyed the moment. The lineups for today, courtesy of the box score on Yahoo.com: Red Sox Schilling, p Angels Weaver, p Angels-Red Sox Game 2 Chat

2007-10-05 16:26

D. Matsuzaka p Von Joshua

2007-10-04 07:58

As far as I knew there never had been a major league Josh and never would be. On closer inspection now I see that there were a few Joshes in baseball’s earlier eras, but none since a couple journeymen named Josh Billings in the 1920s and no one at all of note besides Josh Devore, who had a brief career as a speedy outfielder for the pennant-winning Giants of the early teens. Now, however, baseball is lousy with Joshes. So is everything. After taking a victory lap around my apartment to celebrate Josh Beckett’s dominating game 1 shutout of the Angels (i.e., going to the kitchen to look for chocolate, finding none, and stuffing a piece of rye bread with cream cheese into my face instead) I came back to the living room and watched a couple minutes of a show my wife had just switched to, in which the parents of a young tan mousse-haired douchebag were subjecting a woman with fake breasts to a lie detector test. The mousse-haired douchebag’s name was Josh. “I’m getting together with the rest of the Joshes and voting this douchebag out of our name!” I fumed. But there are so many Joshes now, many of them probably moussed douchebags, that if there ever was a global meeting convened the expulsion votes might end up purging any lingering unmoussed solitary oddballs left over from the earlier less-Josh-heavy days of yore, like me. Banished, I’d have to change my name to some extinct moniker such as Festus or Mortimer or Increase. But until that day comes when I’m forced to roam the land, a name-exile, I can balance the pain of seeing more and more idiots named Josh with the singular pleasure, the boyhood dream, of watching the most important player on my favorite baseball team turn in performances like the one he had last night. Go, Josh, go! Angels-Red Sox Game 1 Chat

2007-10-03 10:08

1. After winning three World Series titles in a row, the roster of the overwhelmingly hirsute A’s was almost completely dismantled within a couple years, as if some secret and severe penalties for over-mustaching had been levied. 2. When Charlie Finley tried to hasten the dismemberment of his A's dynasty by selling two of his stars to the Boston Red Sox, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn disallowed the transaction, citing the damage it would do to competitive balance; however, I believe this justification was a screen to cover the real reason: Rudi and (especially) Fingers would have put the Red Sox, already fairly well-mustached, far over their facial hair allowance. Supporting this point is the fact that Rudi later came to the Red Sox anyway, sporting his modest gun-shop-cashier ’stache, while Fingers, the facial-hair-cap-wrecking A-Rod of the Mustache Years, had to spend some years with the smooth-cheeked Padres of Enzo Hernandez and Randy Jones until the apparent lifting of the Mustache Cap in the early 1980s allowed him to join the malodorous unshaven rabble known as the Milwaukee Brewers. 3. The California Angels and Boston Red Sox constantly shuttled similarly-mustached guys back and forth, as if the deals depended on the equal exchange of facial hair. The unremarkable mustaches of guys such as Jerry Remy and Joe Rudi came east, and the unremarkable mustaches of guys such as Dick Drago and Rick Burleson went west. Even when cleancut guys such as Denny Doyle passed between the two teams the transaction seemed to come with hidden “facial hair to be named later” clauses that impacted (and explained the seeming imbalance of) later trades whose principles, such as cleancut Butch Hobson and walrus-faced Carney Lansford, did not balance out on the facial hair ledger. I’m not quite sure how Rick Miller fits into all this, but when I was a kid he seemed to drift back and forth between the Angels and Red Sox like a Mustache Years version of a Cheshire cat. Because he was obscure to me in each place for different reasons (on the Angels because they were so far away and on the Red Sox because he was always buried on the outfield depth chart), I was never completely sure which of the two teams he was on at any given moment, and so there always seemed at least a shred of him in both places, a brown medium-sized mustache hanging in the clubhouse air, waiting for the rest of him to appear and collect a pinch hit or make a diving grab in the outfield just when you thought for sure he was on the other side of the continent. Anyway, Game 1 is still a few hours away (6:30 P.M. ET, TBS; Gameday info to come if I can figure it out; update: I can't figure out how quite to link to that Gameday box, but you can go to the MLB.com scoreboard and click on the Gameday option above the Red Sox-Angels line score), but I thought I'd open up the conversation about all things Red Sox and Angels a little early. I can't help it. I'm excited, and worried, and also excited, plus a little worried. Will the Red Sox be all right without My Favorite Red Sox, Tim Wakefield, to turn to in times of trouble? Why if there is no knuckleballer would we need Mirabelli and Cash? Will the Red Sox be bedeviled and undone by the speed and daring of the Angels on the basepaths? Will John Lackey’s lack of success at Fenway find its regression to the statistical mean at the worst possible time with him twirling a stunning shadow-aided three-hitter? And, most importantly, should I start growing a Rick Miller playoff mustache? Cubs, 1977

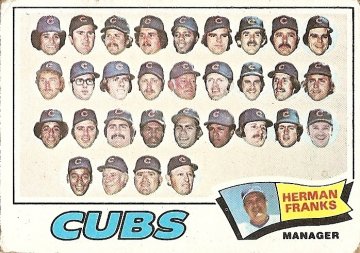

2007-10-02 10:12

I will not be good for much for the next few days, or next couple weeks, or next month, depending on how far the Boston Red Sox can advance in the playoffs (or, taken from a darker angle, how physically and mentally debilitating a premature exit by the Boston Red Sox might prove to be). Starting tomorrow, Cardboard Gods will begin serving as Baseball Toaster's headquarters for Open Game Thread chatter for each of the Red Sox games versus the California Angels. While I may be able to enhance that coverage with some stray memories about the past, I doubt I'll be launching any wrenching multipart excursions into the wistful days of yore anytime soon. It's the playoffs, and my concentration is already a little spotty. My primary goal for October is to not get hit by a bus. Anyway, I wanted to kick off the playoff coverage here at Cardboard Gods by mentioning the team that has the potential to be the biggest story of October 2007. As all baseball fans know, the Cubs have not won a World Series in 99 years, a drought that has gained some added sting in recent years with the long-awaited World Series wins of the Red Sox and, worse, the Cubs' crosstown rivals, the White Sox. For many years the Red Sox, White Sox, and Cubs sat together at the loser table at lunch, duct tape on their glasses, acne on their faces, making each other snicker joylessly by spelling out "boobs" and "hELL" on their calculators as the cool guys sat at the Champions table with all the pretty girls. Now the Cubs are all alone at the loser table, nothing to keep them company but their stale peanut butter sandwich and their disappointing memories. As Merle Haggard might have put if he was a Cubs fan: "The only things I can count on now are my failures." The Cubs had many years when they didn't even sniff the playoffs, which in some ways is a less painful fate than getting so close you can taste it and then caving (if you don't believe me, just ask a Mets fan or a Padres fan today how they're feeling and then compare the response to the feelings of a Baltimore Oriole fan who long ago turned his attention to building a ship in a bottle or porn or whatever one does when not obsessed with baseball). But there have been some awful Cubs moments, especially in recent years. Before the hideous 2003 playoff collapse and the 2004 end-of-season el foldo there were playoff disappointments in 1998, 1989, and, most painfully, 1984, as well as a monumental implosion in 1969 that turned a mid-August World Smashing 9-game lead into a pitifully meek 8-game deficit by the end of the season. Eight years after the 1969 flop, the Cubs authored another lesser-known season of disillusionment. In 1977, the heads pictured in the card above combined with their unpictured necks, torsos, limbs, and other below-the-jaw bodily parts to race to a first-half lead in their division that grew as large as 8.5 games by June 28. They went 34-59 the rest of the way, however, finishing 20 games behind the Philadelphia Phillies. They say that when you get beheaded you are aware of what's going on for a few seconds. You remember that you were once whole and realize that you are no longer. I wonder if that feeling is anything like being 20 games out of the money by season's end, dead as a doornail, and thinking back for one brief second before the final out of the year, remembering how sweet life was in the middle of summer. |