|

Monthly archives: June 2008

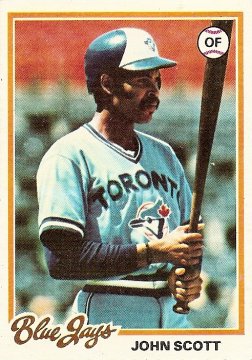

John Scott

2008-06-30 06:59

Exactly one week before his eighteenth birthday, John Scott was selected by the San Diego Padres with the second pick of the 1970 amateur free agent draft. Only one unsigned player in the world, Chris Chambliss, was deemed more promising at that moment. I wonder what it felt like to be John Scott at seventeen, failure a stranger. It took him four years to make it to the majors, and then only as a late-season callup who got into just 14 games. In 15 at-bats, he hit .067. The next season he got into more games, 25, but had even fewer at-bats, just 9, all outs. He didn't make an appearance in the major leagues in 1976, but just after the World Series the Padres, abandoning hope that he’d ever deliver on his prodigious promise, sold him along with Dave Hilton and Dave Roberts to a team that didn’t even quite exist yet. The expansion draft that would stock the roster of that team had yet to occur, and only Phil Roof, who had been acquired the day before, preceded the erstwhile Padres trio as members of the Toronto Blue Jays. In fact, you could make a case that John Scott was the very first Toronto Blue Jay, as he batted lead-off in their first ever regular season game, April 7, 1977, against the Chicago White Sox. This first-ever Toronto Blue Jays at-bat ended in a strikeout. Scott went 1 for 5 in that game, a fairly accurate preview of a season in which he logged 233 at-bats and hit .240 with 2 home runs and a .266 on base percentage. And that was it for John Scott and the majors. At some point during his lone extended chance to prove that he could cut it as a major leaguer, this photograph was taken of John Scott staring directly at his bat. Why have you abandoned me? Where have you gone? I’m begging you. I’m ordering you. I’m begging you. I’m ordering you. I’ll turn you into ash. I’ll build you a shrine. I love you. Don’t leave me. I hate you. Don’t leave me. Failure is never a stranger for long. *** (Love versus Hate update: John Scott's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Jim Mason

2008-06-27 14:41

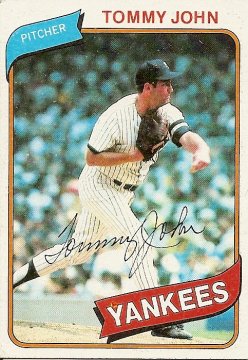

Tommy John, 1980

2008-06-26 09:44

Tommy John was on ESPN radio this morning, and was asked by his co-host for the day about the Hall of Fame credentials of some current pitchers. Maddux, Glavine, and Johnson got a thumbs-up, but Smoltz, Schilling, and Pedro did not. It was clear that John believed the latter three had to get in line behind him. When his cohost tried to float the idea that Smoltz’s many saves should in effect be added to his win total, John pointed out that he had saved a few games himself, implying that such arithmetic would still find him to be Smoltz’s superior (in actuality John compiled only 4 saves). When Schilling’s postseason heroics were mentioned, John said “There’s more to baseball than the postseason.” The last John-rejected pitcher, Pedro, didn’t merit further discussion beyond the stunning one-word denial: Nope. Not long after Tommy John (who as far as I can remember was never the unquestioned ace on his own team) implied that he was a better pitcher than Pedro Martinez, his cohost tried to give him the chance to exhibit a more magnanimous side by asking him what retired player not named Tommy John he would give entry to the Hall of Fame if he could. He chose Bert Blyleven, noting his 287 wins. “One fewer than me,” he couldn’t help adding. Cardboard Books: Black Diamonds

2008-06-25 13:32

In the 1989 oral history Black Diamonds, author John Holway leads a gritty, fascinating tour through the too often neglected world of the Negro Leagues. Among the many players interviewed are a slugger nearly without peer (Hall of Famer Willard Brown); a forerunner of Rod Carew and Tony Gwynn in the highest level of batting wizardry (Gene Benson); a pint-sized flamethrower that some say was every bit as fearsome as Satchel Paige (Dave Barnhill); and one of the greatest competitors the game has ever seen (Chet Brewer, pictured here). As in the oral baseball histories of Donald Honig and Lawrence Ritter, the greatest pleasure in Holway’s book is getting a sense of the distinct shape and character (and characters) of the game as it was actually played. It was a whole different world in the Negro Leagues, with shorter rosters and longer, more perilous road trips forcing the players involved to not only be more well-rounded, worldly, and tenacious than their white contemporaries, but also making them, in general, more passionate and innovative in their study of the game. It’s foolish to generalize about any group as varied as the collection of men who played Negro League baseball, but the impression I get from reading Black Diamonds is that no group ever loved baseball more. A lot of this is all new to me. When I was a baseball-hungry kid I learned next to nothing about the subject. Sometimes Topps included cards that celebrated the more distant reaches of the history of the game, but there was never anything about the Negro Leagues; the baseball encyclopedia I pored over made little or no mention of the Negro Leagues;* and the baseball books from the nearby college library only included enough information to make me think of the Negro Leagues as a shadowy, somewhat backward wilderness, a place to try to flee. About all I knew about the Negro Leagues was that Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron had escaped (the latter's escape one and the same, in my mind, with leaving behind the seemingly laughable habit of batting cross-handed). *(Hey, my first Posnansterisk!) I no longer have this encyclopedia, which disintegrated, and the names of the authors—which were never that important to my stat-greedy kid mind—escape me now, but it was one of the greatest books of my life; I prefer it to others because its focus was not so much on individual players but on highlighting teams and the year-by-year narrative procession of the game (at least the white version of the game), giving each year a title (“The Year It All Became Official”; “Greenberg’s Grand Return”) and offering entire rosters and stats for each team. Does anybody know what book I’m talking about? Does it still exist? And how have I been able to get by without it?) The only exception to this early general misperception of the quality of play in the Negro Leagues was the idea I got somehow, I’m not sure from where, about Josh Gibson. I was first drawn to him because he was the only professional athlete I’d ever heard of that shared my first name, but what made him more than a curiosity was the number associated with his name. I don’t know where I read it, but somewhere I got the idea that Josh Gibson had hit 800 home runs, a number I believed in immediately because my belief in the truth of all baseball numbers was total; conversely, my inability to grasp a general admiration of Negro League players had almost everything to do with the fact that they didn’t have numbers attached to them, or not enough numbers to make them seem substantial. Nothing like 800 home runs. And since Josh Gibson was the only Negro Leaguer with a number like that attached to his name, he was for many years the only African American from the pre-Robinson years to gain entry into the baseball sanctuary in my mind. With his book, John Holway has helped expand my conceptions about this rich expanse of baseball history. (Bill James has dubbed Holway’s work “the most indispensable original research [on the Negro Leagues]”; my thanks to Baseball Toaster commenter Eric Enders for providing a heads-up about Holway in an earlier discussion about baseball books.) I plan to keep reading more about the legends of the Negro Leagues, and would love to hear suggestions for further study. I want to read more oral histories, but I also want to get a sense of the wider arc of the Negro League story. I’m talking partly about the people who shaped the leagues, but I’m also talking about the defining contests. It seems to me a great book could be written detailing the ten best (or fifteen best or whatever) games in the history of the Negro Leagues. Because of the more chaotic nature of the Negro Leagues (players constantly on the move, teams and even whole leagues folding overnight), it’s a little harder to get a strong hold on the whole of that history than it is with the major leagues; I think a book looking in detail at a few definitive games (the players, the stakes, the context, the goats, the heroes) would be a way to help provide some landmarks for someone new to the territory. Anyone versed in this history know of any suggestions for that list? The one that comes first to my mind is the 12-inning duel in 1930 between Chet Brewer and Smokey Joe Williams. Brewer recalls the game in Black Diamonds, bemoaning the bad hop that led to the only run of the game in a way that speaks to his own competitive fire and his deep respect for his counterpart, a man he said “could throw the ball harder than any I played against.” “If that ball had just bounced around the infield,” Brewer says, “we would probably be playing yet.” Steve Dunning

2008-06-24 11:03

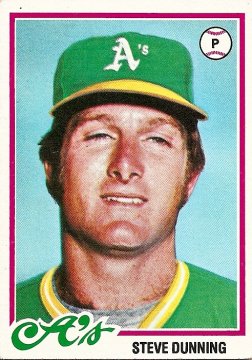

“The older you get, the more rules they are going to try and get you to follow. You just gotta keep on livin', man. L-I-V-I-N.” – Wooderson, Dazed and Confused The 1970s started so promisingly for Steve Dunning, his college heroics prompting the Cleveland Indians to select him in the first round of the amateur draft, that choice seeming to pay quick dividends when Dunning pitched a one-hitter against the Washington Senators that according to Baseball Library.com caused Ted Williams, seldom one to sing the praises of pitchers, to utter that the young hurler was “going to be some pitcher some day.” Just a couple weeks after that booming blessing, Dunning smashed a grand slam home run, the last by an American League pitcher for 37 years, until Felix Hernandez equaled the feat yesterday, an occurrence that has released perhaps for the last time the name Steve Dunning into the general babble of the world, a final puff of seed from a desiccated pod. But almost immediately after Dunning’s slam the young, golden decade started to turn. Dunning was chased to the showers just two innings after his salami by the up and coming Oakland A’s, the lead he’d staked himself to gone in a barrage of sizzling liners and arcing blasts. Years of mediocrity and transience ensued. By the time he reached the A’s he’d played for four other major league franchises and spent large chunks of time in the minors (a step that he’d skipped on his initial rush from college glory to the majors). The A’s themselves had won three World Series titles but had been dismantled and were plummeting into irrelevancy. Dunning pitched sparingly for the gutted squad the season before this card came out, Topps apparently judging his spot with the team too tenuous to dispatch a photographer for a shot of him in an actual A’s shirt and cap. Instead they took whatever photograph they could find and dumped throbbingly bright green and yellow paint all over it. Steve Dunning, never again to appear on a baseball card, seems untroubled by his imminent disappearance into obscurity, untroubled by the apparent vanishing of his youth, untroubled by the unreality all around him, untroubled by doubt. We should all face the void so unshakably toasted, as if a kegger at the quarry is in the offing, and not an irrevocable nameless undoing. *** (Love versus Hate update: Steve Dunning's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Rod Carew

2008-06-23 10:49

Rod Carew was never overpowered by a pitch. Whatever it was, wherever it was aimed, whatever its nasty spin or ungodly hop, he adjusted, flipping the power of the pitch on its ass with the brevity and grace of a martial arts master. Is there any doubt that the plan the catcher pictured here and his unseen battery mate have concocted to foil Carew will fail? Carew will wait in his coiled yet serene praying mantis stance until the very last moment, then use his lightning-quick wrists to strike, lacing the pitch into some unguarded patch of the grass. Who was a more constant part of my internal life when I was a child than Rod Carew? He was always there, at the top of the Sunday averages, the list that meant more to me than any religion. The greatest day of every summer was when my brother and I got to stay up past our bedtime to watch the entire all-star game, and Rod Carew was always among the sparkling selections. Since he had been an all-star before I was born, it seemed to me that he had always been an all-star. It seemed as the years continued to roll by that he somehow would always be an all-star. But in 1985 an all-star game was finally played without him. I was seventeen that summer. I had a freshly earned GED, a job pumping gas, and no plans for the future. What was I supposed to do? Leaving childhood is like having a hole in your swing that continues to get bigger and bigger. The alarming absence in the midsummer classic of Rodney Cline Carew, the owner of a swing with no holes, was the last stage of erosion. How am I supposed to hit when I'm more hole than swing? The Basketball Kid's Official Results

2008-06-21 08:13

A couple hours after I posted the photo of me suffering through my final moments in the 1983 Northfield Mount Hermon Pie Race, my mom sent me the following message in an email entitled "esp exists": "you won't believe what I located, put into an envelope for you, and sent off this morning. [6/18] ...BEFORE I read your day's blog." And so, yesterday's mail: The clipping from the high school newspaper spent the early stages of its existence taped to a yellow cupboard in the kitchen of the house I grew up in. When that house was sold it went into a box, where it has remained for twenty years. It finally got jostled loose the morning I wrote about the Pie Race. As I was writing, my mom, preparing for another in a long series of moves, was going through her belongings, trying to lighten her load, when she found the clipping and put it in an envelope. I spent a disturbing amount of time yesterday scrutinizing the details of the list. It occured to me at some point that I may have underlined my own name, sarcastically, in 111th place. But it's just as likely that my mom did it. She's the one who saved the clipping, after all. A year and a half after the race she had to come and pick me up in front of my dorm before my senior year was over. Sometimes I take for granted that there are people in my life who will highlight my name in 111th place. There are people who cheer for me, who refuse to give up on me, who save things for me. I'd started crying when I called her to tell her I'd been expelled. I was in the office of the campus dean, a guy whose name happens to be the last full one listed in the excerpt of the clipping above. After the phone call I shook his hand, consciously trying to be a noble guy on my day of ruin. I wish I'd gone berserk instead, noting that he was cross-eyed, upending his desk, mocking him for coming in 49 places after me in the previous year's Pie Race. Many of the other names, 550 in all, in the 1983 Pie Race Results carry a similar weight, the list a personal litany of longing, anger, embarrassment, curdled joy, regret. I was 15 and 16 and 17 when I was a name among those names. I never was so excited, so terrified. I never had bigger crushes. I never was so frustrated and lonely, confused and overwhelmed. I never laughed so hard. I never had so many boners. I never got so high. Doug Bird

2008-06-19 09:30

One of Allen Ginsberg’s more well-known poems is "A Supermarket in California," in which he imagines himself side by side with Walt Whitman. "Where does your beard point tonight?" he asks his imaginary companion at one point. I also once wrote a poem about Walt Whitman, during college, and it was published in the campus newspaper, The Basement Medicine. That was during the one year I served as a benchwarmer on the college’s pathetic basketball team. The center on the team, a Laimbeer-shaped freshman named Sean, complimented me on the poem. I don’t know if it was then that I noticed he had pretty putrid breath, or maybe it was another time. A couple years later, I was in the stands when he was on the brink of scoring his thousandth point. I had a camera with me and when he scored his milestone bucket on a short jumper in the lane I caught it on film. I kept meaning to give the photo to him, as it was the only visual record of his feat, but I never got around to it. I still have the picture somewhere. I suppose I could try to Google him, but he has a common last name and would probably be pretty difficult to find. I was always grateful to him for his compliment about my Whitman poem, and also grateful to him for a pickup game that pitted the two of us and three other guys on the basketball team against five guys from the college's championship soccer team. We were more skillful at basketball, having devoted much of our lives to playing it, but we were losers and the soccer guys were winners. I once overheard the athletic director, who was also the soccer coach, say as much one day around the time of the pickup game. "The basketball guys just don’t know how to win," he boomed. He always boomed whatever he had to say. By contrast our coach, a disheveled English teacher, most often muttered. (Sometimes he whined.) During the pickup game the soccer guys looked like they might be able to prove the athletic director's point. I started to get flashbacks to similar semi-official demoralizing basketball contests from my youth. Twice the guys from the grade younger than my grade challenged us to a game, once when I was in 8th grade and once when I was in 10th grade, and both times they beat us. During a battle for a rebound in the grim late stages of the second game, my last contest before I went away to boarding school, my hand inadvertently landed on the face of their best big man and out of frustration I yanked down, throwing him to the ground. The varsity coach was watching from the risen stage behind the basket. He started screaming at me. Luckily the guy I threw down, who could have ripped me limb from limb if he’d wanted to, was one of those genial, slow-to-anger behemoths, and he just stared at me, stunned, as he got to his feet. "Get out of the game, Wilker!" the varsity coach yelled. "Go cool down!" I went into the locker room and I think I cried a little. It was shameful to get beat by younger guys, especially since the beating was implicitly sanctioned by the varsity coach, who looked down on us with disgust. It made me feel like I was nothing. So here we went again a few years later, the soccer champions matching us basket for basket even though basketball was just something they did once in a while when they weren’t winning soccer tournaments, raising championship banners, and having sex with all the prettiest coeds. But eventually we just started feeding our bad-breathed center the ball. Sean was considerably bigger than any of their players, and he had a nice turnaround jumper, which he hit several times in a row to give us a victory that, though it didn’t wipe the smirks off the soccer guys’ faces, at least spared us total humiliation. Anyway, I guess that’s where Doug Bird’s beard is pointing today. I didn't think that's where it would lead but I'm like a saxaphone that's been run over by a pickup truck. Everything comes out crooked, wheezing. I thought I would be able to capture my many feelings about the expression on Doug Bird's face. His mirthful, somewhat unhinged expression and his unruly hair exploding from every available pore makes him look like one of the backwoods guys who used to sail past our house once a year in pickup trucks to get to the nearby Tunbridge Fair. They had girlie shows there in one of the tents that wasn't being used for livestock displays, and though I never went I imagine the audience was full of guys who looked like Doug Bird, drunk, cackling, wearing jeans and red checkered hunting jackets and John Deere hats, stomping their dirty shitkickers on the sawdust to the rhythm of the music accompanying the disrobing dancers, the air laced with the rural carnival aromas of smoke and cotton candy and manure. I guess some people know how to win; the rest of us follow a more crooked path, taking our pleasures where we can. "Yeehaw!" Doug Bird shouts, his beard pointed up at the show. The Basketball Kid Takes a Victory Lap

2008-06-18 06:26

This photo was taken in the fall of 1983, when I was 15 years old. I had been at boarding school for a couple of months. By then I’d played enough pickup basketball at the school to understand that my place in the school’s basketball universe was marginal at best. I looked like my brother, who had directly preceded me at the school and who had served as a human victory cigar on the excellent varsity team, fans chanting for him during blowouts, but I wasn’t as big or as skilled as my brother. I knew this already, even before I’d come to the school. All the teams I’d ever played on had sucked, each season horrific, a Donner Party pantomime, and I’d been far from the best player on even those teams. At the end of the last of those seasons, my 10th grade junior varsity campaign, I told the varsity coach I was going away to boarding school. He had gotten angry with my brother for doing the same a couple years earlier. I was expecting the same treatment, an impassioned lecture on why I shouldn’t leave. He just looked at me and shrugged, then turned back to some paperwork. "Good luck," he muttered. Still, I clung to the hope that basketball would be a way for me to find some place in the world. How could I not? I didn't see that I had anything else. To get in shape for basketball season at boarding school, I took distance running as my fall gym class. A turning point in my life came the day, a few weeks into the semester, when I discovered I could show up for pre-run roll call, then let the instructor lurch way out ahead of me with a pack of untroubled youth who had enrolled in the class, and then veer off the path, dart behind a building, and saunter back to the dorm to laze around for the rest of the afternoon. The seed had been planted: it was frighteningly easy to fake it. But I didn’t seize upon this discovery, at least not at first. I still wanted, at least on some level, to be more than a faker. I went on most of the distance runs, and by the day the above photo was taken, I was in pretty good shape. That day was the running at the school of something called the Pie Race, one of the oldest footraces in America. Everyone who ran the race under a certain time got a pie. When I first saw this photo, a week or so after it was taken by my dorm parent, I was mortified. The kid who had begun to learn how to fake it wanted to be the kid who didn’t seem to care. It struck me as painfully uncool to be captured in a moment of puke-coaxing effort. But it was the home stretch of the race, and even though dozens of runners had already finished ahead of me, reinforcing my status as a marginal, I still very much wanted to do my best. The picture embarassed me. As I look at it now, twenty-five years later, I see a kid who was trying. Soon enough this kid would begin to embrace his lot in life as a marginal type, a goof-off, a loser, but in this moment he’s still trying to miraculously discover himself among the ranks of the winners. If you look closely, you can see a familiar figure on the shirt he’s chosen to wear on the day of the tradition-haunted school-wide race. It’s the same winking, cane-leaning, basketball-spinning leprechaun that, late last night, Kevin Garnett put at the center of his first act as (to use his term) a "certified" winner. Mike Barlow

2008-06-16 07:46

In 1979, Mike Barlow pitched more innings in relief than all but one of his teammates on the division-winning California Angels, but he recorded no saves and was involved in only two decisions, winning one and losing the other. Barlow did not get into any of the first three hotly contested games of the best-of-five American League Championship series, watching from the bullpen as the Baltimore Orioles took Game One on a John Lowenstein home run in extra innings and watching the teams trade one-run victories in Games Two and Three. In the top of the ninth inning of Game Four, with the Orioles ahead 8-0 and just a few moments from wrapping up the pennant, Mike Barlow got the call. He pitched a scoreless frame as seats emptied and exits filled. Had the Angels been able to stage what would surely have been the greatest comeback in post-season history in the bottom of the inning, he would have been the winning pitcher, perhaps the answer to a trivia question, but the Angels went down meekly. Significant things tended not to happen when Mike Barlow was involved. He's not the answer to anything. * * * I watch a lot of sports. When you watch sports you end up watching a lot of advertisements. These advertisements often call my inner strength into question. I am asked if "it" is in me. I am urged to kill the coward within. I can’t remember at the moment any of the other current slogans. But I know that I need a more muscular body than the one I have, and a more competitive nature, and a faster car, and less self-doubt, actually no self-doubt. But fuck all that. If there’s a coward within I’m not killing it. I’m not killing anything. The whole idea seems kind of fascistic, actually. If there’s a coward within me I’m inviting it out to join me on the couch and watch sitcom reruns. I caught part of one yesterday, a Seinfeld where George initially recoils from the opportunity to have an affair with a married woman. "An affair?" he says, wincing. "That’s so . . . grown-up." Who wants to grow up? * * * Later, I called my dad to ask him about Moshiach. I’d just finished reading The Yiddish Policeman’s Union and I wanted to know more about this figure that most of the people on my dad’s side of my family tree spent the last few thousand years waiting for. "Yes, my mother and father spoke about Moshiach when I was growing up," my dad said. "The idea is he’ll come and there will be peace on earth, a return to Eden." The Yiddish Policeman’s Union features a figure being looked to with unendurable need as Moshiach. This man can’t bear the pressure of everyone’s hopes for redemption. He desires more than anything to disappear, to be insignificant. * * * Who wants to be in the middle of the action? Not me. I want to be a mop-up man. If I’m ever officially involved, I want the announcers to be telling stories that have no connection to the action on the field. I want to hear the sound of foul balls clattering around vacant sections of seats. I don’t want to hear the roar of the crowd. Most of the time I’d rather just watch, leaning on a fence, daydreaming, drowsy, a towel around my neck like the towel draped around a fighter as he’s being led away from a fight, the trainer reassuring the fighter that it’s over, that there’s no more need to punch and get punched. Chris Speier in . . . The Franchise All-Time All-Stars

2008-06-12 06:06

Before embarking on another foray into the recurring feature started a couple weeks ago with a post on Jerry Koosman, I wanted to emphasize three things about the project: 1. It’s already been done, and with much more expertise, reasoned analysis, and entertainment value, by Rob Neyer in his Big Book of Baseball Lineups. So why do I feel the need to tackle the already thoroughly tackled subject? Which brings us to . . . 2. It’s a way for me to goof off. If I wasn’t publicly airing my choices for the greatest players ever to wear the clown cap of the Montreal Expos I’d be filling up my empty hours by thinking about it privately anyway. So why don’t I just keep my flimsy impressionistic baseball opinions to myself instead of polluting the Internet with them? Which brings us to . . . 3. I’m interested to hear other people’s opinions on the matter. Nothing I like more than a good baseball conversation, especially if the conversation mostly ignores recent events to burrow into the past. Which brings us to . . . The Montreal Expos and the surprising discovery that the greatest shortstop in franchise history might be the scowl-faced man pictured above. Mike Cosgrove

2008-06-10 06:25

* * * Johnny Wockenfuss

2008-06-06 07:21

The first year my world expanded beyond my house and yard, I got a bully. He intercepted me in the afternoons after kindergarten, stepping in front of me when I was on my way home. One day he showed me a little pen knife and said he was going to carve me up if I didn’t find a way to climb through a small tree that had split at the trunk into two thick, tightly entwined branches. I spent what seemed like a very long time trying to climb through the nonexistent space between the branches. For most of that time I was afraid to look up from the task, and even when I finally did and saw that my bully was gone I kept trying for a while, afraid that he’d somehow know that I had defied him. Another day he was starting to menace me with a fallen branch bigger than either of us. My best friend Nick happened to come by. Steve Yeager

2008-06-04 07:05

Steve Yeager was known for a greater number of things than the usual good major league catcher. For comparison, consider Jim Sundberg, Yeager's contemporaneous counterpart in defensive excellence in the American League. Sundberg stuck to the usual catcher script: catch games, blend into background. On the other hand, the mention of Yeager's name conjures many things beyond the usual realm of the anonymous receiver. Here are some of those things, not including his role as Duke Temple in Major League, Major League II, and Major League: Back to the Minors: 1. Being Chuck Yeager’s cousin. Imagine being a longtime starter on one of the marquee teams in major league baseball and still being second banana at the family reunions. "Hey, Chuck, check out my World Series MVP award." "Hey, that’s great, Steve (even if you did share the award with two other guys). Oh, by the way, here’s a picture of me after I became the first human being to break the sound barrier." 2. Almost dying in the on-deck circle. A shard from Bill Russell’s broken bat hit him in the neck, puncturing his esophagus. (You know you’re an injury pioneer when your esophagus gets involved.) To protect Yeager’s beleaguered body part the Dodgers trainer created the first throat protector, which soon became part of every catcher’s protective armor. I’m pretty sure Yeager never wore the throat protector in the on-deck circle, which casts an odd light on the invention. It’s kind of like getting hit by a car and then inventing something that protects you from getting hit by trains. 3. Posing in Playgirl. For some reason on the rare occasions when the subject of Playgirl comes up, I always think of a line uttered by Paul Newman’s grizzled player-coach in Slapshot about the relative pulchritude of the male body: "Dicks. They ain't petunias." 4. Converting to Judaism. You could make the case that Steve Yeager deserves the starting spot on the all-time Jewish baseball player all-star team. There haven’t been that many nice Jewish boys willing to don the tools of ignorance. There was the colorful, defensively apt but offensively inept Moe Berg, early 1960s Dodger backup Norm Sherry, and current longtime weak-hitting, good fielding catcher Brad Ausmus. Mike Lieberthal is often also mentioned in discussions of Jewish ballplayers, but he seems to be pretty vehement about not wanting to be identified as a Jew. (I believe that, like me, Lieberthal’s father was Jewish. I proudly consider myself a half-breed, embracing neither Lieberthal’s apparent denial of his roots on his father’s side nor the orthodox Jewish belief that if a person’s mother isn’t Jewish that person is not at all Jewish.) I’d say all things considered Yeager tops all those guys, so if you’re willing to overlook the fact that he wasn’t actually Jewish while he was playing and instead concentrate on his willful post-career embrace of Judaism, he gets the starting nod, catching Sandy Koufax and taking his place in the following batting order: Benny Kauff (CF), Rod Carew (2B) (I follow Jonah Keri in including Carew), Hank Greenberg (1B), Sid Gordon (LF), Al Rosen (3B), 5. Being one in a long line of good, if not excellent, Dodgers catchers. A couple days ago, hard on the heels of Manny Ramirez’s 500th home run, Batter’s Box wondered if Red Sox left fielders comprise the single best position of any franchise in baseball history, mentioning Ramirez, Duffy Lewis, Ted Williams, Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Rice, and Mike Greenwell. The ensuing conversation there and on the Baseball Think Factory turned up several contenders for the honor, including among many others Yankees centerfielders and first basemen, Cardinals first basemen, Browns/Orioles shortstops, and Giants first basemen. The first thought that came to my mind when I saw the topic was Yankees catchers. I wasn’t the only one to think of this. But no one mentioned the same position for the Dodgers. But consider all the Dodgers catchers named by Bill James as among the 100 best of all time (their ranking follows their names): Roy Campanella (3), Mike Piazza (5) (when the rating came out it was based almost entirely on his time with the Dodgers), Johnny Roseboro (27), Mike Scioscia (36), Steve Yeager (78), Joe Ferguson (79) (the journeyman had a few career-representative seasons with the team in question), and Mickey Owen (88). The Yankees' list is probably a bit stronger--Yogi Berra (1), Bill Dickey (7), Thurman Munson (14), Elston Howard (15), Wally Schang (20) (see note for Ferguson), and Butch Wynegar (65) (see note for Ferguson)--especially considering that Jorge Posada deserves to be added somewhere pretty near the top, but the Dodgers' backstops, current star Russell Martin included, are certainly no slouches. You could do a lot worse than a future Jew-embracing thespian willing to injure his esophagus and bare his petunia. Darrel Chaney

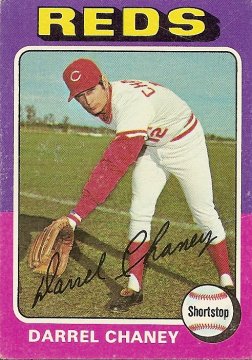

2008-06-02 11:04

Last night I dreamed a guy on my high school ultimate frisbee team was hitting me grounders. He was a coke-doing senior who liked to cacklingly saddle younger students with annoying, inescapable nicknames. (I think he was behind people calling me Beeker.) I don’t know why he was in my dreams, but I was having trouble getting in front of the grounders he was hitting to me. This was always a problem for me in all sports and in life in general—I am a coward. If the rare chance coming my way takes a bad hop I’d rather it not hit me in the chest or face or nuts. I’ll take a swipe at it, but if that doesn’t work I prefer to deal with the consequences: humiliation, disappointment, being disappointing. Unfortunately I have become an expert at numbing all the things that accompany a squandered chance. On the other hand, Darrel Chaney strikes me as the kind of guy who would stop grounders with his teeth if he had to. It would be difficult to explain his presence for several years in the major leagues otherwise. He lasted for eleven seasons despite batting just .217 with a .288 slugging percentage. Something of a negative image of the best of the all-star Big Red Machine infielders he occasionally spelled, Chaney also augmented a notable lack of power with an inability to steal bases. The back of the card text backs up the theory that his worth resided in his ability to deal effectively with ground balls, describing him as “an outstanding glove man.” (Interestingly, considering a somewhat gruesome aspect of the Mannerist portrait on the front of the card, no mention is made of his throwing arm.) I don’t know if I would have been able to write about Darrel Chaney if his hard-nosed talents had been better represented by the photo on his card. I realized today that one reason I have written relatively few profiles of Cincinnati Reds players from the 1970s is that I can’t really relate to excellence. So Chaney, a tough, humble, do-anything-to-help-the-team-win utility guy on a couple pennant winners and a World Series champion, would leave me nothing to connect to had he been shown in a photo bravely turning a double play despite the marauding spikes-high efforts of a baserunner. But that is the beauty of my Cardboard heaven. All become strange and failure-laced. Here Chaney stoops like an arthritic amputee with one freakish arm as long as his legs, his eyes mean slits, his skin pale, his lips thin and sour, like those of a corrupt medieval bishop. He reaches for an imaginary grounder, not getting in front of it. He reaches for his shadow. It eludes him. He reaches for his name. He’ll catch a shred of it, the top loop of the D, but no more, as it slides past him and disintegrates. He will remain forever on this side of the white chalk line. |