|

Monthly archives: December 2008

Todd Van Poppel

2008-12-31 07:42

This is a common question at this time of year among kids, those purest of getters from our getting-crazed society. At a certain point we're supposed to become givers, I guess, at least for one day a year, but the constant rhythm of getting that riddles the modern world reveals that we're all still kids at heart, happy and hungry to get. Me, I got a lot of good and useful stuff from the kind givers in my life, but the gift that may have given me the most pleasure is the stack of baseball cards that my wife's aunt gave me. She was in a store that had several cellophane-wrapped stacks, and she bought the one that had a Red Sox player on top (some guy from the strike-fouled years of 1994 and 1995 that I actually don't remember: Carlos Rodriguez). In the stack were cards from 1987, 1990, and 1995, plus a couple basketball cards and several football cards. My obsession with my distant personal past has prompted me to be somewhat rigid in my unsaid policy that my baseball card collection is closed, that I'm not making any additions beyond the cards that came to me when I was a child. But if there's one lesson I can learn from the year that's about to end, it's that it's good to be open to new gifts. Cards keep coming to me, either half-buried in the mud or torn up at a bus stop or from kind readers offering to fill in glaring gaps in my collection. This latest gift was no exception. The cards were all more recent than the cards I collected as a kid, but since I neither collected these newer cards when they came out nor dwelled on them constantly in my writing they seemed to come from a more distant time. Tom Brunansky? Ron Kittle? Juan Berenguer? These names all seemed to be singing to me from a farther and more mysterious remove than the now-familiar names of the more distant past. Each card in the stack gave me something--hilarity, excitement, even joy--but none sent a shiver through me like the card shown here. Todd Van Poppel stands out in my memory above all the other hyped prospects that have come and gone in my lifetime. I’m too young to have noticed the similar ambiguous ascension of David Clyde in the early 1970s (though I was around to witness the aftermath), and somehow the explosion of baseball information available through the internet has dulled the impact on me of any noise about talented prospects in most of the years since Van Poppel debuted as a 19-year-old in 1991. That’s the year I got out of college and entered the so-called real world. I must have read about Van Poppel in the newspapers I plucked off the top of street-corner garbage cans on my way home from the graveyard shift at the UPS warehouse up in Hell’s Kitchen. I’d get off at eight or nine in the morning, depending on how many packages had to get loaded that day, grab a discarded newspaper, check it for heinous residue, buy some three-for-a-dollar mac and cheese and the cheapest beer and hot dogs I could find, and carry my goods up six flights to the narrow railroad apartment I shared with my brother, who by then had left for his office job, and there I’d wolf down my chemical-glutted feast and guzzle beer in the morning light and read about Todd Van Poppel. Todd Van Poppel was going to be great. There was no doubt. When there was nothing left to read or eat or drink, I’d go to the back of the apartment and pull out the futon and pass out for several hours, until it was time for my new work day to begin at dusk with a shower and oatmeal and the 5:30 rerun of Charles in Charge. *** There’s nothing like a supremely dominant high school pitcher. I’m talking about myth, the kind of myth that offers the illusion of the obliteration of doubt. Myths can rise up around a dominant high school slugger, but somehow it’s not quite the same, as an observer will be more likely to discount their outrageous statistics as the byproduct of lesser competition. But the image of a pitcher mowing down high schoolers before a scattering of family members on aluminum bleachers seems to transfer more easily to an image of that same pitcher mowing down pros in front of a roaring stadium, probably because a key element of a pitcher’s gifts can be measured: the velocity of his pitches. And if a mere high schooler is already making radar guns short-circuit orgasmically, then it seems a given that he’ll continue to throw unhittable smoke in the majors. But there’s something else about the dominant high school pitcher that makes him more of a mythic figure than any other prospect. Alone out there, standing tall on the mound, unhittable, he’s what we all dream of being. To have that power in our fingers. To have the future seem like something that will only come to life with our powerful touch. To have it waiting for us and us alone. To be a fan is to dream. Who didn’t want Todd Van Poppel to become a legend? Who didn’t want to dream through Todd Van Poppel? *** This 1995 card shows Van Poppel’s first three seasons in the pros, none of them revealing much promise. The amazing thing about Van Poppel, who is generally and cruelly thought of as the gold standard of busts, is that he ended up lasting for a long time in the majors. He even (mysteriously, given his struggles before and after) had two strong seasons as a reliever with the Cubs in 2000 and 2001. In all he logged 11 seasons at the highest level of his supremely competitive profession, his career spanning 14 years, all the way from 1991 to 2004. I'm tempted to fall into withering comparisons between those years for Todd Van Poppel and those years for me. But on this special day, the last day of the year, I want to try to limit my focus to the card-slim moment between past and future. Today's a good day for this. Among all the baseball-card-shaped squares on the calendar, the last day of the year is the one most like a baseball card. The past is simplified to a series of lists such as the statistics and highlights on the back of a card, and the future has no more depth than a card-front photo of a figure standing tall, hands on hips, gazing sternly off into the distance. Who doesn’t at some point on this day hope that somewhere in the back-of-the-card stats there is some subtle upward trend, some sign that the coming year will be better than the ones that have come before? "After dropping his first three decisions in the Majors," states the text on the back of the card shown here, "Van Poppel capped the 1993 season with six victories in his last nine decisions." There is no mention of the following season, in which Van Poppel went 7 and 10 with a 6.09 ERA. This is a normal omission for baseball cards and last days of the year. You try not to dwell on things like failure, humiliation, disappointment, regret. Likewise, you think of the future not as a minefield of anxiety and discouragement but as an uncomplicated distance to stride across, a mountain to scale, a series of batters to fan, a line for the back of the card that will make all the lines preceding it seem like a strange, soulful prelude to happiness. Cardboard Books: The Year in Reading

2008-12-29 15:11

When I’m not working or sleeping or staring at baseball cards or the television, I’m reading or walking to the library to get some more books. I guess there are a couple other miscellaneous activities I engage in now and then, but that’s pretty much what my life boils down to. This year, for the first time in my life, I kept track of what I read. Good thing, too, because if I hadn’t done that I’d have surely forgotten most of the books that passed through my brain. I forget most things that happen to me. Whole years go by in a blur. But at least this year I know what I read. I’d like to keep this brief, just pass along a few titles that stood out to me and turn it over to you all for thoughts on any books you’ve read this past year that stood out. I’ve already got a stack of books waiting for me in 2009, but I always like hearing suggestions on what I should add to the pile. (I have an annoying habit of not getting around to following people's suggestions for years, but a few baseball books mentioned by readers in comments on this site—The Celebrant, False Spring, The Greatest Slump of All Time—did make their way into my reading list for 2008.) One thing my list-keeping told me was that my reading basically breaks down into four major groups: fiction, sports, music, and the rereading of favorites. So here are my 2008 highlights from each category. Favorite Revisitation of a Personal Favorite This 2007 publication may not actually qualify for this category. The scroll, in fact, is an altogether different book from the previously published classic, one of my all-time favorites and maybe the most important book, personally speaking, that I’ve ever read. The scroll is more direct, more honest, wilder. Allen Ginsberg got it right in his first reaction to the scroll years ago, when he called it “dewy.” The real question for me is, when I go to revisit On the Road again in a year or two, which version will I turn to? I think I might go for the Scroll. Honorable mention in this category goes to Bruce Jay Freidman, one of my all-time favorite guys. A year would not be complete without a dip into one of his classic novels from the 1960s and early 1970s. This year’s selection was About Harry Towns, a sad and hilarious novel about a middle-aged man adrift in the coke-addled early stages of the Me Decade. Favorite Music Book Favorite Sports Book Favorite Fiction Book First, a salute to Australian writer Tim Winton. He was my favorite “discovery” of the year. It’s pretty silly to consider him a discovery, since it’s not exactly a secret that he’s one of the best fiction writers in the world, but the sad fact is I hadn’t heard of him before this year. I read a couple of his books this year, The Turning and Breath, and loved them both. The first is a book of interconnected short stories about working class people in a somewhat desolate coastal region in Australia; the second is a coming of age novel in the same setting. Second, some shout-outs to the novels that yanked me all the way out of this world and into that other world behind the page: The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, Netherland (the only book I read all year that actually came out in 2008), and The Road. I read a lot of good books this year, but these were the ones that stood out in their ability to pull me into their worlds, which after all is what I’m most looking for when I read. It sounds like I’m looking for escapism, but why would I want to escape, for example, to The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s horrifically convincing gaze into the apocalypse? I’m not sure why, but maybe there’s something in all us readers that wants to connect with a wider, deeper current of meaning than the one that we’re connected to for most of our waking hours. I know I’m always feeling better about things if there’s a good book bouncing around in my knapsack. Anyway, my favorite book that I read this year was actually the first book I read in 2008: Tree of Smoke, by Denis Johnson. I've already mentioned this book at some length during my long Born in the USA series, so I guess I'll just wrap things up, finally, and turn it over to you. So how about it, what were some of your favorite reads this year? Jesus Alou

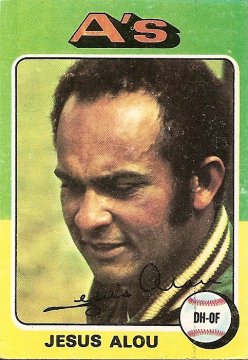

2008-12-24 07:31

Once, during the first December I remember, a car barreled into our yard, tearing up some bushes, and my mom made wreaths out of the wreckage. The wreaths signaled that the big day was getting closer. When Christmas finally came, I got the gift I’d been wishing for, from the FAO Schwartz catalog I’d been using as a prayer book: a fist-sized green metal combat van that shot small yellow rubber missiles from guns in its roof. Freshly unwrapped, it felt heavy, solid. I’m tempted to say it felt magic, even holy. There was nothing better than Christmas. There was nothing better than getting things. And boy, did I get things. My family lived on the cheap throughout the recession-stung 1970s, and there were times when we were just barely scraping by. A yearly pre-Christmas tradition was my mom tearfully telling my brother and me that because of money troubles "Christmas isn’t going to be the same this year, boys," a claim we learned to shrug off because every Christmas morning the lower half of the tree would be obscured behind a mountain of presents, like always. It was my favorite day of the year, and no other day even came close. I got and got and got. By the end of the hours of unwrapping I was always high from candy and getting, my arms resting on stacks of brand new things. It was always a little sad to come to the last present, that moment like the first strand in the gradual unraveling of the feeling of holy solidity given to me by all my new things. Those things all broke, eventually, or were lost. None of them have made it to the present moment, and only a few exist in my memory. I did recently replace a gift from a long-ago Christmas. Maybe it was a gift for my brother and me, or possibly even a gift for my brother that I took co-ownership of. It came from my uncle during the day's second stage of gift-getting, when my extended family gathered: a Neft and Cohen baseball encyclopedia. Its size and the tiny type and all the numbers seemed daunting, a grown-up thing, but below that there was something calling to me, saying that there was a place for me somewhere in that book. Eventually it became my bible. This was in 1974. I’d gotten my first baseball cards that year, just a few. In 1975 I began to collect even more. It can’t be an accident that my biggest childhood hobby, by far, included key elements from my favorite day of the year: wishing, unwrapping, sugar, and getting. This card came to me that year, and I’m sure it made an impact. Jesus? A guy named Jesus? (I certainly didn’t know at that time that the player actually pronounced his name Hay-Soose.) And not just any guy, but a balding, troubled man with lines and bulging veins marking his face, seeming as if he’d just discovered that he’d locked his keys in his car again. Jesus came into my life that day, but not the flawless cherubic Jesus afloat in the carols my extended family sang every Christmas as my brother and I took turns on our new Mattell Electronic Football and ate peanut brittle. No, this was a new Jesus, an imperfect sweating journeyman with waning numbers and decreasing playing time. This was the Jesus that would in a tiny but persistent way stay with me as all my other childhood gifts scattered to the various landfills of this holy finite world. Dock Ellis, 1977

2008-12-22 07:00

Dock Ellis got sober in 1980, the year after his notable major league career came to an end. From what I can gather, he spent his remaining years helping others. In fact he had already begun reaching out to help others during his career, often going into prisons to talk to inmates, where he learned not only that he could get through to people in difficult situations but that it was for him something of a calling. In a 1989 epilogue to Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball, author Donald Hall provides a glimpse into Dock’s post-baseball career: "Dock’s desire remains clear and passionate, or it remains passionate and turns clearer. He wants to work with addicts from the ghetto who, in support of their addiction, turn to crime and are slammed away. . . . He works with young, mostly black, who never had anything, by talking. Dock has always been a talker; now it is his profession and moral duty. ‘The first thing they tell you, they didn’t have anybody to talk to. No one to talk to.’ In order to talk to them, he is prepared to settle down after a lifetime of jetting around. ‘If I’m working with kids, I’m doing what I want to do.’" (pp. 333-334) Dock always had the guts to do what he wanted to do. During his years as a high profile major league star, this kind of bravery made him an outspoken, polarizing character, vilified by some but honored by others, including Jackie Robinson, who near the end of his own life personally reached out to Ellis to encourage him to continue taking stands when he saw fit. Ellis’ exploits could fill a book, as indeed they did in the aforementioned classic by Ellis and the future United States Poet Laureate. It’s certainly worth it to spend some time today remembering Dock, who passed away on Friday, as he was in the 1970s spotlight, and the links below are provided toward that end, but think also of the Dock who existed out of the spotlight, away from the game, where his life could be an illustration of the line in the Wailers "Pass It On": "Live for yourself, and you live in vain. Live for others and you live again." Check out Jay Jaffe’s Futility Infielder for an excellent retrospective of Ellis’ career. Be sure to follow the link Jaffe provides for a great rock song inspired by Ellis. Click on this link to hear audio (below a slide show) of Ellis describing the no-hitter he pitched while on acid. At the end of the audio there is the actual radio call of the final out. Visit the Griddle’s post on Ellis’ passing (this is where I learned the sad news) to read a story by commenter Eric Enders about a friendly and memorable meeting with Dock Ellis at the site of old Forbes Field. And, finally, check out some video about Ellis’ appearance as an All-Star game starter in 1971: Doug Ault

2008-12-19 07:11

Middle row, fifth from the right. I think that’s Doug Ault. It’s the only trace I have of him in my collection besides his name on the back of this card. It’s one of the few names with a blank box next to it. As the summer of 1978 went on and all the other boxes on the back of this card started to fill, I must have begun dwelling on Doug Ault’s name and the empty box next to it. *** Four years ago this Monday, Doug Ault left a note for his wife in their kitchen. It's the kind of note you never want to find. "Look in my car. Doug." *** If my brother didn’t have doubles of a Doug Ault card that I could try to trade for, then the only other method I could employ to try to fill in the box next to Doug Ault’s name was to wish for him, to believe that he existed even though I couldn’t see him, to believe he somehow knew he was needed, to believe he was somehow being pulled in the direction of that need, to the middle of nowhere where I was. *** Doug Ault was the first Toronto Blue Jay to homer, doing so in the first inning of the team’s inaugural game. Two innings later, he hit the second home run in franchise history. What must it have felt like to connect that second time? Ault had played a few homerless games in the major leagues the year before, with the Texas Rangers, but they’d left him unprotected for the expansion draft. After his Opening Day barrage, he would hit only fifteen more home runs in his career and be out of the majors by 1980. But forget what came before and what followed. Doug Ault is rounding the bases, a member of a team that had not even existed the year before, that had come into existence wanting him, naming his name in the expansion draft, and he’d hit two home runs in his first two at-bats. His whole body must have been buzzing as he rounded first, then second, then third, as he reveled in the roar, as he stomped on the plate. Here I am, motherfuckers! Doug Ault! Home! *** Why did I wish for cards I didn’t have when I was a kid? Why do I hold on so tightly even now, thirty years later, to the cards that I do have? I don’t really know. But I know there are good moments, moments of connection, moments of feeling at home in this world. I also know there are moments that aren’t even moments but empty boxes next to your name. The emptiness within the borders of that box is bottomless. You feel your name being pulled toward it. You feel like you don’t have the strength to fight the pull. If you have something, anything, to hold on to, hold on. Alan Ashby

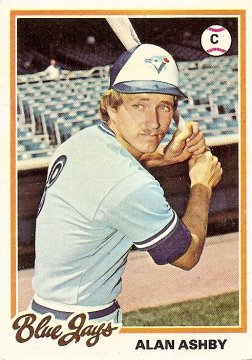

2008-12-17 06:05

I was born into losing. This may seem like a particularly glum and self-pitying thing to say, but facts are facts: I was the younger sibling of an athletically able boy who would always be older, bigger, and stronger than me. This may not have had such an impact on my sporting won-loss record had my family remained throughout my childhood in kid-glutted suburban New Jersey, where I was born, but just as I was getting old enough to be able to perform sports-related tasks, such as throwing and catching a ball, my family moved to rural Vermont, where the great majority of the time the only game in town was the one that pitted me against an older, bigger, stronger boy. *** During the Cardboard Gods era, i.e., the heavy card-collecting years of my childhood, i.e., 1975–1980, the 100-loss plateau was surpassed nine times. The Tigers, Expos, Braves, and A’s all had a season during that span in which they suffered over 100 losses; the Seattle Mariners had two such seasons; and the team of the player featured here, the Toronto Blue Jays, lost over 100 games not once, not twice, but thrice. And they weren’t even in existence for the first two years of the era. *** Perhaps because I was born into losing, I spent a lot of time fostering fantasies of victory. I was willing and able to do this on my own, but I loved when my brother joined me, either as we rooted for the same team to win or as we bounded around our big side-yard pretending to be key members of the same winning team. Our baseball team was the Boston Red Sox, but when the weather started getting cold and the trees turned skeletal we shifted our attention to football. The only channel we got reception for that showed football was CBS, which featured the Dallas Cowboys nearly every week. They usually won. After those wins, we’d go out into the cold fading day and for a little while pretend to be Roger Staubach and Drew Pearson connecting for touchdown after touchdown. *** A look at the Toronto Blue Jays’ 1977 roster might lead one to believe that the team’s executives decided to field a team of players that just happened to fall to them, like a collection of damaged drifters who all end up in the same run-down coastal outpost, drinking tequila shots at tables for one and nervously keeping an eye on the door. But in fact the team was built with a conscious plan and not by mere apathetic passivity. The plan may well have had a long-term element to it, especially considering that within a decade of their birth the Blue Jays would be contending for division titles, a development their fellow 1977 expansionists, the Mariners, fell far short of attaining. But whether there was a long-term element to the plan or not, the existence of trades made by the team in its early moments shows that the franchise was not merely naming players when forced to by the expansion draft but was seeking out players on other rosters and actively devising ways to bring those players onto their own roster. It seems, through this lens, that the Blue Jays decided that if they were going to have any structural integrity at all they would have to make sure to have able catchers, those players often referred to as "backbones" of teams. The first trade they ever made, for a player to be named later, was to acquire veteran catcher Phil Roof. The first trade they ever made where they actually had someone on hand to offer in return came about a week later in an Expansion Day trade of Al Fitzmorris for Doug Howard (who would never play a game for the Blue Jays) and Alan Ashby. Ashby would serve as the team’s first regular catcher, the first backbone, the first rock upon which the tower of the franchise would be built. *** Ashby became an official member of the team just as it was starting to get cold, in November, the time of year that found my brother and me pretending to be Staubach and Pearson. My brother always eventually grew bored with that shared side-yard fantasy. He either quit to go climb deep into one of his science fiction books or decided it was time we played against one another. Our one-on-one matches went the same way in every sport we played, but they were stripped to their grimmest essence in the wake of the Staubach-to-Pearson fantasies. I’d punt the ball to my brother and he’d Robert-Newhouse through me for a touchdown, then he’d punt the ball to me and I’d have it for a few seconds before he grabbed me, ripped the ball from my hands, tossed me aside like a candy bar wrapper, and ran for another touchdown under the cold gray sky. *** Alan Ashby went on to play for seventeen years in the major leagues, most of those seasons as the on-field shepherd of the often-dominating Houston Astros pitching staffs of the early 1980s. But he never caught more games or logged more at-bats than in that first long season with the Blue Jays. As mentioned earlier, the catcher is often thought of as the backbone of a team, but the catcher is also a team’s most intimate witness. The catcher can see all the other players on the field at all times, and unlike the three outfielders who also have a comprehensive view the catcher is involved in every play at close range. All season long Alan Ashby had the best view of the daily pummeling the team was sustaining, run after run stomping down on the plate in front of him as he held his mask in his hand, doing nothing because there was nothing to do. The photo shown in the 1978 card at the top of this page shows this witness to monumental failure looking a little guarded, a little sad. An aura of powerlessness emanates from his bunched shoulders and placid, introspective features. But there must be in this photo evidence of a tenacious will, too. A full ten years after presiding over the 107-loss season, a 35-year-old Ashby recorded career highs in home runs, RBI, batting average, and just about every other offensive category. Everyone’s born into losing. Can you bear witness to the losing and continue to show up, year after year? *** Ben Henry homers in final at-bat

2008-12-15 05:31

Tom Seaver, 1978

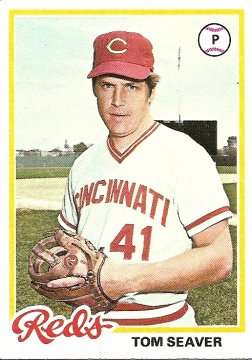

2008-12-11 05:49

"There is actually a good argument that Tom Seaver should be regarded as the greatest pitcher of all time." – Bill James I. Degrees of greatness are difficult to define, but baseball analysts have approached these kinds of definitions by devising ways to adjust raw data for different conditions in different eras. The most effective single statistic of this kind, for pitchers, is ERA+. While ERA+ cannot tell the whole story of a pitcher, it seems to do a better job of it than any other single statistic. Four of the top ten seasons in ERA+ were recorded between the years of 1994 and 2000. Fourteen of the top 52 seasons in ERA+ were recorded between the years 1990 and 2005. By comparison, only three top-52 seasons occurred during a similar span of years directly preceding this recent era, only three in the fifteen years before that, and just two in the fifteen years before that. You have to go all the way back to the deadball era, an era so slanted toward the pitcher that even ERA+ seems unable to adequately adjust for it, to find a similar explosion of otherworldy pitching seasons, as defined by ERA+. Discounting the deadball era, you are left to conclude that, in terms of elite pitching performances, the era we all had the pleasure of recently witnessing was about three times as magnificent as any era preceding it. Three times as magnificent? Something seems fishy here. II. First of all, I don’t know how to make a graph. A graph showing the recent stark jump in the number of astounding single seasons in ERA+ would do a nice job of illustrating the idea that something went wacky in the machine, that some element of ERA+ may not have been able to adjust to all the conditions and factors producing the raw data of the recent era. Second of all, and more importantly, I’m not so good with numbers. If you had told me when I was a kid that I’d grow up to make such an admission, I’d have been surprised. Throughout my baseball-card loving childhood, I loved numbers. This is what the backs of baseball cards were all about, after all: numbers. Stacks of numbers, numbers that swelled and waned like the tide, numbers that gleamed, numbers that wheezed, clownish laughable numbers, awe-inspiring numbers, numbers that seemed to tell stories clearer than anything else in the world I was just beginning to wake up to, ambiguous, slippery, forever uncertain. The 1978 card shown at the top of this page brought to a close what was perhaps the most magnetic running saga-told-in-numbers of my childhood, for the year before this card came out, while being traded from the Mets to the Reds, Tom Seaver fell four strikeouts shy of 200, the first time in a decade he had failed to surpass that plateau. On first glance at the back of the card, it seems he has fallen well short of 200 not once but twice, since there are two lines of statistics for the 1977 season, one for the Mets and one for the Reds. Once that initial disappointment passes, there is the secondary disappointment of adding his strikeout totals for the two teams together, putting those fourth-grade math skills to use, almost but not quite getting to 200. All things must come to an end. Yet still, above those two sums that don’t quite add up to a hundred, there is that pillar of 200s, nothing quite like it in all the world of the Cardboard Gods. Nobody hit over 40 home runs every year, or even over 30, not even Hank Aaron. Nobody drove in over 100 runs every year. But Tom Seaver struck out over 200 every year, again and again and again. But words don’t do the feat justice. You have to have been a kid, holding one of his baseball cards in your hands, looking at that invincible ladder that stretched all the way back to the beginning of time, i.e., to the year you were born. As I grew up, numbers began to overpower me. Coincidentally or not, at the same time I started reaching for inebriating substances of one sort or another, as if my inability to any longer make sense of the world by using numbers produced a need in me to become as senseless as possible. I still remember my trigonometry final exam my junior year at boarding school. It was part of a giant testing period for many classes in the gym. After looking over the test, which repelled me like a force field, I spent most of the time until the bell writing an apology to my teacher in one of those blue examination booklets. It may as well have been my suicide note to the world of numbers. Right around that time, a senior drove up over the border, to Vermont (my school was in western Massachusetts), where the drinking age was still 18, and bought so many bottles of booze that when he got back we spread them out on a kid’s bed and took a picture of them. So many bottles you couldn’t even count them all. The giddiness was palpable. We were about to blast all the numbers clean out of our heads. III. Or is there some flaw in the ERA+ statistic, some nuance that hasn’t yet been accounted for? I don’t know, man. Let’s face it, I’m way over my head. In fact, this post is more than anything an invitation to one and all to throw a math-dufus a lifeline. My one thought, and probably it’s elsewhere either been better expressed or eloquently discounted, or both, is that maybe the staggering ERA+ numbers of Pedro and Maddux and Randy Johnson and Clemens and even Kevin Brown (numbers that seem to argue for the superiority of all these pitchers save the last one over such standouts from previous eras as Tom Seaver) have something to do with the expansion of the league during that time. This explanation has often been used to hypothesize about the reasons for the ballooning numbers of hitters. Talent is thinned out, allowing star hitters to shine all the brighter by all the fat, inexpertly thrown pitches and by comparison to all the lesser batters allowed by expansion to enter into the league. But for some reason this very same line of thinking has not been used, at least not commonly, to try to explain the outrageously good numbers of some pitchers during the 1990s and early 2000s. I don’t see why not. If the town you grew up in suddenly added several more little league teams, wouldn’t the burly early-puberty kids with armpit hair not only hit more home runs but, when on the mound, garner more strikeouts and scoreless innings? And wouldn’t those pitching numbers look even more breathtakingly dominant when compared to the pitching numbers of a skinny bespectacled feeb forced, because of the thinning of the league’s talent, to leave the safety of deep right field to take repeated tear-laced beatings on the mound? After all, Tom Seaver was known as the Franchise when he was on the Mets, a nickname that of course ties him to the identity of the team, a nickname that says that if anything in this world is certain, it is that Tom Seaver is the Mets. And yet, here he is, in a Cincinnati Reds uniform. And not only that, but on the back of the card, his string of 200-strikeout seasons, that towering pillar of numerical certainty, has finally reached its end. When I got this card I probably gazed for a while at the odd spectacle of the Reds jersey on Tom Seaver, and then I probably gazed for a while at the back of his card, adding two sums to make a number less than 200. Then I probably looked back at the front of the card and stared into Tom Seaver’s eyes. It doesn’t matter, he is saying. The numbers, the uniform. None of it. What matters, what is certain, is this: Give me the fucking ball and I’ll get you a win. Greg Maddux in . . . the Nagging Question

2008-12-09 07:02

I’m tempted to go with Tom Seaver, because I marveled at his feats as a kid and count a game I saw him pitch at Fenway in his last season among the most memorable games I've ever attended. I was 18 that year, 1986, and I am pretty sure I went to the game alone, the only time I’ve ever done that. I must have taken a bus in from my grandfather’s house on the Cape, where I was spending the summer pumping gas. I could look up the game on retrosheet, but I prefer to just rely on my memory, which has me in the centerfield bleachers and Seaver on the mound in a duel with a young flamethrower named Mark Langston, a guy who is not exactly a household name now but who at that time, because the pitches springing from his left hand were as fearsome as a snapped and writhing power line, seemed to be at the beginning of a splendid career, dawn to Seaver’s dusk. While the whip-thin youngster racked up the strikeouts, the stocky old-timer craftily navigated through occasional jams, never allowing his calm claim on the game to be disturbed. My strongest memory from the game has to do with this last thing, his calmness. I remember getting the sense, even from the centerfield bleachers, that as Seaver stood on the mound looking in for the sign and drawing in a slow breath he was as calm as the Buddha, aware of and at peace with the fact that he was the center of the game, the center of the world. The game finally swung his way late, when Langston came undone. As I recall it, an error played a part in the go-ahead rally, just enough of a tremor to push Langston off his center, something that did not happen to Seaver that day. I couldn’t imagine it happening to Seaver any day. The young ace of the Red Sox staff that year, on the other hand, as great as he was, proved in the coming years capable of coming undone from time to time. Still, I think many people around my age would have, up until some fairly recent events, argued that Roger Clemens was the best pitcher of their lifetime. His reputation has taken a hit of late because of revelations about his use of performance-enhancing drugs, and I guess the general belief is that his career numbers, especially those compiled late in his career, should be downgraded with the caveat that he may have gained an unfair competitive advantage by going on the juice. Even before all that came to light, I don’t think I would have been able to embrace Clemens as a choice for the best pitcher of my lifetime, because, fairly or unfairly, I see him in my memory allowing the occasional big moment to overwhelm him, to turn him into an unfocused raging bull falling off his axis at the center of the game. His successor as ace of the Red Sox, Pedro Martinez, fares better in my memory. My first memory of him is always the performance he turned in against the Indians in the playoffs in 1999. Unable because of arm trouble to throw fastballs, Pedro nonetheless pitched several innings of no-hit relief by masterfully baffling the Cleveland hitters with an assortment of off-speed junk. Even stripped of his most fearsome weapon, the mound was his. For that, and for all the games I watched him pitch when he did have his full arsenal, I would say that no one in my lifetime has reached the level of dominance that Pedro performed at during his prime. However, while Pedro was dominating the American League throughout the steroid era, another master was putting up similarly jaw-dropping numbers while dominating the National League. And he had been pitching at a high level for several years before Pedro ever reached the major leagues, and in the last few seasons, while Pedro has struggled mightily to stay off the disabled list, this pitcher who predated him has continued to log big innings and win his share of games. I never got to see much of this latter pitcher, Greg Maddux, in his prime, but he did return to his first team, the Cubs, the same year I moved to Chicago, so I got to watch him a few times in his sunset years. Some games went well, some not so well, but either way he always remained unflappably poised, like that 1986 version of Seaver. He also had a springy looseness all his own that I found inexplicably enjoyable to watch. In fact my most vivid memory of Maddux in his second go-round with the Cubs is the way he covered first base on a grounder. To be more specific, I see him just after he has expertly executed the play to end the inning, flipping the ball straight from his glove to the first base ump with an almost playful nonchalance. It’s often been said of Maddux, because of his stocky frame and nondescript features, that he looks more like an orthodontist or an accountant than an elite athlete. But I think you would only need to have watched him moving around his workplace for a couple minutes to see that Maddux, who yesterday announced his retirement, was as much at home on a baseball diamond as Seaver or Clemens or Pedro or anyone else who has ever lived. Frank White

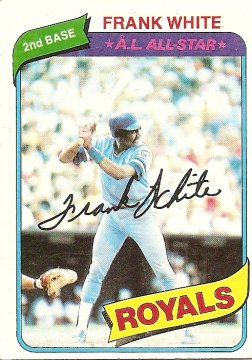

2008-12-08 04:50

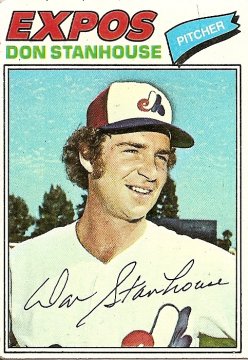

A long time ago I read an article about Frank White that had some information that has stuck with me. White described a time in his playing career when the stress of holding down a major league job began to overwhelm him. He was unable, during down time away from the park, to focus on any one thing. Instead, he would have a magazine open and the TV on and the radio blaring and a record spinning on the turntable, his attention like a hummingbird trapped in an electronics store, flitting from one barren babbling source to the next, never landing anywhere, instead only becoming more and more exhausted. I may be remembering the article incorrectly, but I think Frank White saw that earlier way of living as a time when he was bordering on mental illness. Unfortunately, I can’t recall how he pulled himself out of that habit, or even be a hundred percent sure that he was recalling the everything-all-at-once episodes from a remove or rather still trying to find a way out of them. All I know for sure is that Frank White was, as this 1980 baseball card reports, an All-Star. In my mind he was as constant a presence in that annual game as anyone from his era, and since he was not a magnetic superstar such as Pete Rose or Reggie Jackson there was something even more solid about his presence in the midsummer classic than other more well-known perennial all-stars. Superstars weren’t always super, year-in and year-out, instead rising and falling and rising in magnitude and magnificence, but Frank White was always Frank White, kind of in the background, no national commercial endorsements or magazine cover spreads, a constant presence in the exalted exhibition, his prominence or role never changing. I think the reason I still remember that article that described the way he unraveled into a powerless mess at the mercy of his in-home sources of entertainment is because I am still a little disturbed that the solidity of Frank White was a mirage. Everyone, even Frank White, is clinging to the ledge by their fingernails. Don Stanhouse, 1977

2008-12-04 06:16

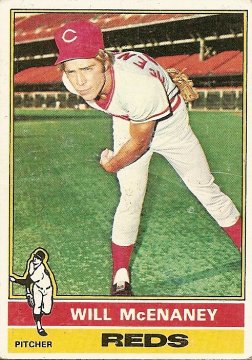

My fandom has been and most likely always will be one defined in large part by substantial distance. When I was a boy, I used to fantasize that one day the great gap between me and the players I idolized would be closed. The central fantasy in what was actually a foggy cluster of vague fantasies was the one that began when I sent a letter to Carl Yastrzemski, asking for his autograph. As the months and years went by without a reply, I came to accept that a reply would never come while simultaneously fantasizing about a preposterously familiar reply: a long personal letter from Yaz, or a phone call, or even a visit. As I got a little older, edging into my teen years, my prevailing fantasy shifted to a bizarre hope that one day while shooting baskets alone on the hoop in my family’s driveway in rural Vermont, a passing limousine would slow to a stop so that its passenger, Dr. J, could (depending on how deeply I wanted to escape my life at that moment) ask me over to chat for a few minutes or go have some Burger King with him or sign me up to an NBA contract. I’m not really sure why I imagined Dr. J in the limousine and not a member of my favorite team, the Celtics, but it might have something to do with the mythic aura that surrounded the Doctor in my youth. He was a storybook figure, magical and legendary, and slipped easily (much more so than the pasty grunting lurching figures clad in Celtic green) into the realm of fantasy. I wish I could say I long ago surrendered this kind of fantasizing about the gap closing between me and my gods, but when I got married in Chicago a couple years ago I included several members of the Boston Red Sox (who I had learned would be in town that day to play the White Sox) on the invite list. I am not insane, at least not yet the kind of insane that requires a padded cell, so I did not actually expect any one of them to actually attend the wedding or respond to the invitations, but still I found myself at times in the customarily stressful lead-up to the Big Day imagining myself at some point during the reception leaving the spotlit side of my bride to share a few private edge-of-the-room man-to-man words with the Red Sox’ captain, Jason Varitek. Anyway, Manny and Youk and the rest of the gang were not among the loved ones at my wedding, so I have still never had any contact with the athletes I root for or mock or look to for guidance. All my life I’ve been talking to the gods with no response. But recently, on this site, one of the gods spoke back. Below are the two messages from the world I’ve never known except from far, far away (and given the enigmatic and/or threatening nature of the messages, far, far away is where I'll stay unless perhaps the gap is bridged by a punch in my face). Preceding the two messages is a comment that the Cardboard God seems to be referring to when he mentions "votes." (No one else had mentioned any voting, but there had been other disparaging comments from disgruntled Dodgers fans.) 19. 68elcamino427 Will McEnaney

2008-12-02 05:52

I. When you were a kid, did you dream of an ideal life for yourself in the future? I guess I did, but most of the time only very vaguely. I must have known instinctively that keeping such visions foggy and only partially imagined helps numb the pain when they fail to materialize. I can think of a couple exceptions to this general rule, both having to do with my team, the Red Sox. One dream was actually more of a vow, which perhaps explains why I made sure to make it come true: I decided that no matter where I was when it happened, I would make it to Boston for the victory parade if the Red Sox ever won it all. It was a good dream for me to have, it turns out, for it allowed me to be anything and anywhere, and in fact even implied that my adult life would be one that included rootlessness and drifting. The other dream was in this regard a polar opposite, as its success rested on a sturdy, rooted adult life: I dreamed that one day I would be a season-ticket holder at Fenway. The dream was born in joy. Do you remember the first time you ever came up the tunnel into the stands at a major league baseball game and caught your first glimpse of the green diamond? I’d guess that most baseball fans hold tight to the magic in that memory. My dream of being a season-ticket holder may not have flickered to life in that moment, but when I learned that such a thing as going to every single home game was possible I’m sure my enjoyment in fantasizing about doing so was based in part on that first dose of glowing green. A life built on top of that joy: how could it fail to be a good life? II. III. "As it is," I’d say to my 12-year-old self, "I can barely afford my usual couple tickets in the nosebleeds when the Red Sox make their annual visit to the city where I reside, Chicago. Face it, kid, you are doomed to grow up to be an anonymous guy far, far away from the action." My 12-year-old self would be unnerved by this news, the pain in his eyes gradually turning to panic. "But if I’m not going to be a fan when I grow up," he’d ask, "then who the hell will I be?" IV. I started this morning with a baseball card, a 1976 Will McEnaney. In the lower left of the card is an icon of a pitcher. The 1976 cards all had these icons showing an ideal version of the player’s position—left-handed pitcher, right-handed pitcher, catcher, first base, second base, shortstop, third base, outfield. I would venture to guess that few, if any, of the cards from that year featured the real player so closely aping the ideal player as the Will McEnaney card. In fact, Will McEnaney appears to be someone here who knows nothing about pitching (and, judging from his pained, ironic expression, cares even less) and is inexpertly contorting his body into a pantomime of a pitcher by imitating some idealized version of a southpaw. This is no way to go through life, twisted toward some ideal. V. Kid, you’ll be a fan. Just not quite the kind of fan you thought you might be. In fact, you’ll be very much the kind of fan you are now. Far away from the action. Riddled with distance and solitude and doubt and nauseating boredom and self-absorption. Your fandom will involve the radio and gaps in information and your imagination attempting to fill the gaps. It will involve baseball cards. It will involve holding these cards in your hand and trying to make sense of the actual world. It will at times resemble a quiet strain of mental illness. It will at times resemble prayer. |