|

Monthly archives: February 2007

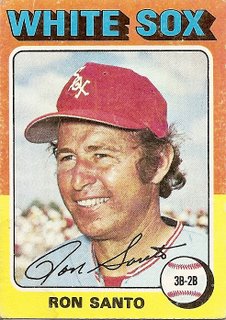

Ron Santo

2007-02-27 13:48

Here's

Ron Santo's last card, the only Ron Santo card I own. It will probably

look a little jarring to Ron Santo fans, who are accustomed to seeing

their affable hero in a Cubs uniform. I can't recall what my thoughts

were on looking at this card for the first time as a seven-year-old,

but I was probably captivated by the long run of impressive statistics

on the back. The numbers weren't in quite as small a type as those on

the 1975 Harmon Killebrew card that so fascinated me, and the numbers

didn't have peaks quite as high as those on Harmon Killebrew's card,

either, but they were incredibly consistent, even more consistent than

Killebrew's, year after year of 30 home runs and 90 to 100 RBI. I'm

sure I also noticed the precipitous dropoff in the last season listed

on the card (5 home runs, 41 RBI), and maybe I even saw it as a sign

that the man's long career was coming to a close. I don't know. In

later years I came to understand that Santo's achievements were even

more admirable given that they came in an era when "benchmark" numbers

such as 30 homers and 100 RBI were inordinately hard to come by, that

the offensive prowess was augmented by consistently stellar glovework

at third base (attested to by 5 gold glove awards), and that Ron Santo

did all this while managing an illness, Type 1 diabetes, that doctors

had predicted would put him in the grave by the time he was 25 years

old. He is still alive today, though he has lost both his legs to the

disease. He works as a Cub broadcaster, and since I live in Chicago now

I listen to him from time to time. He is, by his own admission, an

incredibly biased homer for the Cubs, but for some reason I don't find

this as grating as I usually do when having to listen to other renowned

homers (such as John "Thuuuuuuuuuuuuh Yankees Win!" Sterling of the

Yankees or Hawk "He Gone" Harrelson of the White Sox). Though he

doesn't have the eloquence of the old Mets announcer, Bob Murphy, he

does share Murphy's relaxed, wide open manner, his voice like Murphy's

telling some part deep inside you "Take it easy, partner, you're safe:

It's summertime." Or maybe it's just that he seems like a nice man. Here's

Ron Santo's last card, the only Ron Santo card I own. It will probably

look a little jarring to Ron Santo fans, who are accustomed to seeing

their affable hero in a Cubs uniform. I can't recall what my thoughts

were on looking at this card for the first time as a seven-year-old,

but I was probably captivated by the long run of impressive statistics

on the back. The numbers weren't in quite as small a type as those on

the 1975 Harmon Killebrew card that so fascinated me, and the numbers

didn't have peaks quite as high as those on Harmon Killebrew's card,

either, but they were incredibly consistent, even more consistent than

Killebrew's, year after year of 30 home runs and 90 to 100 RBI. I'm

sure I also noticed the precipitous dropoff in the last season listed

on the card (5 home runs, 41 RBI), and maybe I even saw it as a sign

that the man's long career was coming to a close. I don't know. In

later years I came to understand that Santo's achievements were even

more admirable given that they came in an era when "benchmark" numbers

such as 30 homers and 100 RBI were inordinately hard to come by, that

the offensive prowess was augmented by consistently stellar glovework

at third base (attested to by 5 gold glove awards), and that Ron Santo

did all this while managing an illness, Type 1 diabetes, that doctors

had predicted would put him in the grave by the time he was 25 years

old. He is still alive today, though he has lost both his legs to the

disease. He works as a Cub broadcaster, and since I live in Chicago now

I listen to him from time to time. He is, by his own admission, an

incredibly biased homer for the Cubs, but for some reason I don't find

this as grating as I usually do when having to listen to other renowned

homers (such as John "Thuuuuuuuuuuuuh Yankees Win!" Sterling of the

Yankees or Hawk "He Gone" Harrelson of the White Sox). Though he

doesn't have the eloquence of the old Mets announcer, Bob Murphy, he

does share Murphy's relaxed, wide open manner, his voice like Murphy's

telling some part deep inside you "Take it easy, partner, you're safe:

It's summertime." Or maybe it's just that he seems like a nice man.Regardless

of whether he's a nice man or not, he is ranked by the foremost expert

in such matters, Bill James, as the sixth best third baseman of all

time, and the 87th best player of all time at any position, including

pitcher. And today, once again, the Veterans Committee of the Hall of

Fame neglected to vote him into the Hall of Fame. Today the pompous,

arrogant, condescending (why do I keep envisioning the smug visage of

Joe Morgan?) Hall of Fame Veterans Committee neglected to vote anybody

into their club. Not Luis Tiant. Not Minnie Minoso. Not Gil Hodges. Not

Tony Oliva. Not Ron Santo. Tommyrot. Sheer, unadulterated tommyrot. Tommy John, 1978

2007-02-26 14:55

Mes·mer (mĕz'mer), Franz or Friedrich Anton 1734--1815. Austrian physician who sought to treat disease through animal magnetism, an early therapeutic application of hypnotism. mes·mer·ize (mĕz'me-rīz') tr.v. --ized, -iz·ing, iz·es 1. To spellbind; enthrall: "he could mesmerize an audience by the sheer force of his presence" (Justin Kaplan). 2. To hypnotize. Wil·ker (wĭl'ker), Josh. Born 1968. American proofreader who rode public transportation a lot. wil·ker·ize (wĭl'ke-rīz') tr.v. --ized, -iz·ing, iz·es 1. To mar or erode the value of, paradoxically as a result of both neglect and an overly needy sense of attachment: "I have tons of wilkerized [baseball] cards" (Anonymous). 2. To damage by way of ineptitude or overly crude handling: "Too much cursing. The posting was wilkerized" (Earl Fibril). 3. To squander: "But, alas, I had spent the entire evening smoking marijuana resin through a punctured Sprite can and watching old episodes of Kung Fu. My chances of graduating had been wilkerized." (Butch Pixis III) Of the four definitions listed above, only two of them are actually to be found in either of my two dictionaries, the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, and Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. OK, yes, wilkerize has not yet found its way into the official records of language, which I suppose should not be surprising since I only began to push for its wider usage three days ago in this extremely obscure forum while ruminating on the greatness of Harmon Killebrew. A more surprising exclusion from my two fairly recent dictionaries (both published since the year 2000) is the term Tommy John surgery, which in both tomes should be but isn't tucked in between tommy gun (or Tommy gun) ("a Thompson submachine gun") and tommyrot ("utter foolishness"). By comparison, Lou Gehrig's disease is listed in both books, leading me to believe that, even though Gary Cooper, or even Gary Coleman, never starred in a movie about Tommy John, Tommy John surgery has a chance to someday make it into the dictionaries. In fact, I'd go so far as to say that the term Tommy John surgery is currently used more often than the term Lou Gehrig's disease. I don't know how these things are decided, but maybe there's a word counter somewhere, a guy with a big blackboard who makes a mark each time a nondictionaried word (such as "nondictionaried") is used, then when the predetermined limit is reached he rings a bell or sends a message via suctioned pneumatic tube to some more influential cog in the high-stakes dictionary racket and the higher-up in turn adds the word to the canon. It won't be long for this to happen to the term Tommy John surgery, I think. The annual late-February, early-March spike in the usage of the term has become a herald that winter is on its last legs: every year at this time, news reports on the recovery of hurlers who have recently undergone Tommy John surgery abound. What baseball fan doesn't enjoy such stories? It's always a pleasant read, because it's always about guys you sort of forgot about who are coming back. You may have even assumed they were through, but here they are again, possibly even stronger than ever, thanks to good old Tommy John surgery. Anyway, the inclusion of the term in the dictionaries will of course immortalize the man it is named after, Tommy John, pictured here in 1978 at the very crest of what was at the time a miraculous comeback from arm trouble. In 1974 he had been the first athlete to get the now famous surgery, and he had then sat out the 1975 season with the odds of his ever pitching again placed at a hundred to one by his surgeon, Dr. Frank Jobe. In his early thirties during his recovery, not a young man in terms of athletic life, Tommy John must have had thoughts throughout the long exile that he might never come back. But come back he did, compiling a decent 10-10 record in his first year with a reconstructed arm (at the time, due to the popularity of the Six Million Dollar Man television show, Tommy John's repaired appendage was often referred to as being "bionic"), then in 1977 helped lead the Dodgers to a pennant with a 20-7 record that would have been a shining accomplishment for anyone and was downright astounding for a man who had just a couple years earlier been basically marked for athletic death. More amazing still, Tommy John went on to play for a total of 26 seasons in the major leagues, racking up even more post-surgery than pre-surgery victories. He hasn't yet made it into the Hall of Fame (in the most recent voting he was named on 22.9% of the ballots, far short of the required 75%), but even if he never does his name will certainly live on after him. As befitting a man who had his most, well, mesmerizing moments in sunny, optimistic Dodger blue, Tommy John will soon enough become enshrined in our lexicon as part of a term that has come to signify a kind of all-American nexus of can-do medical acumen, athletic prowess, and never-quit regenerative spirit. Here in America we can do it! We can fix what is broken! We can come up with a solution! We can return from the disabled list! We can heal the sick! We can feed the hungry! We can maybe even purify and renew the seemingly hopelessly wilkerized! Harmon Killebrew

2007-02-24 15:38

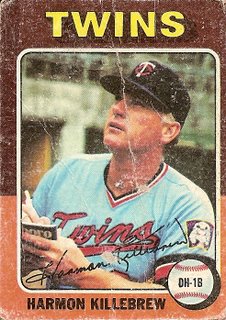

I don't know much about baseball card collecting, but I am familiar with the term mint,

which is used to describe cards that have been held to the greatest

degree possible away from life and its universal slant toward

deterioration. I think there are other gradations below this topmost

designation, but I doubt there are any so far removed from mint

that they could be applied to this 1975 Harmon Killebrew card. My

incessant childhood pawings have pushed it beyond the limits of the

language of commerce. In a monetary sense, it has been ruined. Handled

too much, clung to too tightly. It's now the opposite of mint. I fear

leaving nothing behind when I pass from this earth, so please allow me

to offer a new term to serve as the baseball card collecting omega to

the alpha of mint: Wilkerized. If this term catches

on, maybe years from now, after I myself am deteriorating in a potter's

field grave, perhaps I will live on in a conversation something like

the following: I don't know much about baseball card collecting, but I am familiar with the term mint,

which is used to describe cards that have been held to the greatest

degree possible away from life and its universal slant toward

deterioration. I think there are other gradations below this topmost

designation, but I doubt there are any so far removed from mint

that they could be applied to this 1975 Harmon Killebrew card. My

incessant childhood pawings have pushed it beyond the limits of the

language of commerce. In a monetary sense, it has been ruined. Handled

too much, clung to too tightly. It's now the opposite of mint. I fear

leaving nothing behind when I pass from this earth, so please allow me

to offer a new term to serve as the baseball card collecting omega to

the alpha of mint: Wilkerized. If this term catches

on, maybe years from now, after I myself am deteriorating in a potter's

field grave, perhaps I will live on in a conversation something like

the following:Young man hoping to sell his baseball cards to buy some weed: So, how much can I get for this Ken Griffey the Fourth (With I-Tunes) card? Sports Memorabilia Store Owner: Are you shitting me? Look at it. I mean, the fucking thing's been completely wilkerized. (Author's note: I don't even require that the word be initial-capped.) Young man hoping to sell his baseball cards to buy some weed: God damn it. Anyway, while the specific contours of most of my long ago baseball card daydreams are lost to me, I do remember the draw this wilkerized 1975 Harmon Killebrew had on me. There were three reasons why I kept going back to it, handling it, memorizing it, gradually making it begin to disappear: 1. The name. Every good religion needs a way to move toward the ecstatic unsayable via the pathways of sound. Chanting, singing, speaking in tongues, rhythmic prayer: all these things help take a person out of their everyday self and into another state of being. Not having a religion of my own, I unknowingly invented certain quasi-religious elements around my fascination with baseball cards. In the case of the Harmon Killebrew card, I not only seized on the fascinatingly unusual name but eventually began chanting it to myself at times, pronouncing it not as Harmon Killebrew himself probably did but in such a way that every syllable was stressed: Har! Mon! Kill!Eh!Brew! Har! Mon! Kill!Eh!Brew! I chanted it again and again in my head, the name like drums going faster and faster. I was an odd little boy. 2. A sense of greatness. I was just learning the basic language of baseball statistics in 1975, and so took in Harmon Killebrew's long litany of 40-homer, 100-plus RBI years with the pure and enthusiastic fascination of the true beginner. I have an attraction to anonymous players, to failure and ignominy, to the fallen and the wilkerized, but I am as drawn to the players whose feats stand in bold opposition to the general entropy of the universe as any other baseball fan. I am sure that I found this card soothing. There is greatness in the world. There are things that won't be forgotten. 3. A sense of age. This may have been the most important of all the elements that drew me to this card. The picture on the front of the card hints of what struck my seven-year-old self as great age, in both the gray hair poking out from the cap and in the name that I probably figured must have only existed in a time long before the current era. But it is on the back of the card that this sense of time and history has its most powerful expression. Unlike most other cards, which fill up the empty spaces on the back left by the brief list of years in the major leagues with minor league stats and large-type bullet-item lists containing such information as "Tommy led Eastern League First-Sackers in Putouts," this Harmon Killebrew card only had room to list in unusually small type a line for each of Harmon Killebrew's many, many seasons in the major leagues. Harmon Killebrew had basically been playing baseball forever. The first few years, which occurred long before I'd even been born, were spent on a team, the Senators, that no longer even existed. They were, like the wooly mammoth and tyrannosaurus rex, long extinct. And yet, here was one of them, an Original Senator, alive and well and still grayly slugging home runs. I was drawn to this not only for its mysteriousness but also for the odd feeling of comfort it gave me. I sensed at times that I was an infinitesimally small speck, inconsequential and frail in an unfathomably large expanse not only of space but of time. The universe went on forever and time stretched forward and backward forever and I was an almost-nothing within it. But Harmon Killebrew was something, and I could hold onto Harmon Killebrew. Dennis Johnson

2007-02-23 08:49

No

cards today. Below is a link to a clip of one of the two or three

happiest moments of my sports-watching life, and it would have been a

non-event if Dennis Johnson hadn't known exactly what to do:

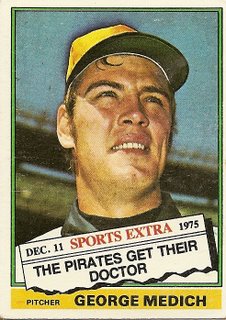

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43DrapEn5QA My favorite part whenever rewatching this clip over the years has been the look of unadulterated happiness on Bill Walton's face. That and Johnny Most's call, of course. But this time I most enjoyed the part when Bird and the man he called the best player he ever played with come together after the play: We're nowhere without each other. Rest in peace, DJ. Doc Medich

2007-02-21 06:24

On December 11, 1975, Doc Medich was traded for Dock Ellis. On December 11, 1975, Doc Medich was traded for Dock Ellis.Though I've come to understand that these two individuals differed considerably, for a while I couldn't get straight who was who. Certain obvious facts eluded me, such as that Dock Ellis was a black man, unlike the man pictured here, and beyond that that he was renowned for some unusual and strikingly distinguishing escapades occurring in the years just prior to the beginning of my attention to baseball. All I knew was that two guys who played the exact same position and seemed to me to have basically the same odd, cartoonish, old-timey nickname had been the main figures in what was deemed at the time to be a one-for-one trade with a couple negligible throw-ins. Doc for Dock. It made me happy. One of those throw-ins in the trade, unfortunately, turned out to be a young second baseman named Willie Randolph. In 1976, while Doc Medich turned in a mediocre season for his new team, Willie Randolph and a resurgent Dock Ellis excelled, helping the New York Yankees end the longest pennant drought they'd ever had, not counting those golden pre-Ruthian years. Luckily the Reds kicked their ass in the 1976 World Series, but in the following season Ellis was dealt to the Oakland A's for Mike Torrez, who helped the Yankees take the final step back to baseball supremacy with two complete game victories in their 1977 World Series triumph over the Los Angeles Dodgers. The repercussions of the Dock Ellis for Doc Medich deal continued the following year, as the Boston Red Sox, starstruck by Torrez's post-season heroics, signed the pitcher to a free agent deal, and Torrez served up enough ill-timed meatballs to hand the fateful 1978 one-game playoff to his former team. At the conclusion of that game my brother ripped one of his beloved James Blish Star Trek books in half. I stomped around looking for something to kick, never really found it, and in a certain sense have been looking ever since. Almost thirty years now with that vague, uncentered, I-want-to-kick-something feeling. . . Anyway, before the Doc Medich for Dock Ellis trade occurred, the Yankees were a bunch of harmless nobodies, and the world itself was harmless, and I was such a happily ignorant young dufus that I was unable and unwilling to distinguish between Dock Ellis and Doc Medich. And by the time the last of the chain of events set in motion by the Doc Medich for Dock Ellis trade had occurred, I was begging my mom to allow me to spend my allowance on a pinstriped shirt with "Yankees" across the chest and the word "Suck" (more of a no-no back then than it is now) blaring in lurid red graffiti across the stomach. My deepest wish by that time, the thing I prayed for whenever tossing a coin into a fountain or pulling on a wishbone, was that the Red Sox win the World Series. But a fairly close second to that wish was that I be able to walk through a divided world in a "Yankees Suck" shirt as the silencing stomach punch of puberty loomed. I like to think I'm not the only one disturbed by these changes. Maybe Doc Medich himself had some inclination that the Doc for Dock trade was going to unleash some foul cosmic repercussions. "Aw, dude," the grimacing just-traded Doc Medich seems to be saying here. "Who cut one?" Alex Johnson

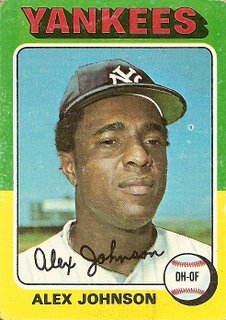

2007-02-19 13:28

Here

is the third 1975 Yankee card in a row to be featured on Cardboard

Gods, the fourth if you include the upper-left section of the Bobby

Bonds Man of Constant Sorrow collage. Prior to this current streak,

I've posted images of Yankee players just twice, once to hurl

obscenities at Reggie Jackson and the other time to admit (not without

some guilt and shame) that as a young child I reacted gleefully to the

news of Thurman Munson's death. It may then seem strange that I have

been spending the last week or so meditating on Yankee players to such

a level of autohypnosis that I eventually went so far as to imagine the

infamous Yankee cap insignia as being a doomed couple's last perfect

dance. In general, the interlocking NY insignia has an effect on me

akin to that of Beethoven on Alex DeLarge after he undergoes his

"treatment" in A Clockwork Orange. But the truth is I wasn't

born with this revulsion. Not until 1976, when Graig Nettles and Mickey

Rivers ganged up on Bill Lee and maimed his pitching arm during a

Piniella-the-Gorilla-instigated bench-clearing war with my team, the

Red Sox, did I begin to hate the New York Yankees. This hatred grew

exponentially over the next couple years, and, on October 2, 1978, became just about as permanent a part of the much-doctored Josh Wilker baseball card as anything can be. Here

is the third 1975 Yankee card in a row to be featured on Cardboard

Gods, the fourth if you include the upper-left section of the Bobby

Bonds Man of Constant Sorrow collage. Prior to this current streak,

I've posted images of Yankee players just twice, once to hurl

obscenities at Reggie Jackson and the other time to admit (not without

some guilt and shame) that as a young child I reacted gleefully to the

news of Thurman Munson's death. It may then seem strange that I have

been spending the last week or so meditating on Yankee players to such

a level of autohypnosis that I eventually went so far as to imagine the

infamous Yankee cap insignia as being a doomed couple's last perfect

dance. In general, the interlocking NY insignia has an effect on me

akin to that of Beethoven on Alex DeLarge after he undergoes his

"treatment" in A Clockwork Orange. But the truth is I wasn't

born with this revulsion. Not until 1976, when Graig Nettles and Mickey

Rivers ganged up on Bill Lee and maimed his pitching arm during a

Piniella-the-Gorilla-instigated bench-clearing war with my team, the

Red Sox, did I begin to hate the New York Yankees. This hatred grew

exponentially over the next couple years, and, on October 2, 1978, became just about as permanent a part of the much-doctored Josh Wilker baseball card as anything can be.But I am rediscovering that there was a brief time when the Yankees were just another team to me. I was seven years old when I obtained this Alex Johnson card, just beginning to get into baseball, and had not even been alive the last time they'd won anything. I had begun perusing a baseball encyclopedia given to me and my brother by my uncle, but, too young even to know about the Fisk-Munson melee in 1973, I hadn't yet been driven by any wounding or enraging current event to meticulously study the long history of Yankee domination over the Red Sox. I didn't hate the Yankees. I didn't hate anybody. I certainly didn't hate Alex Johnson. Why would I? He was just some guy on some team. Everything about Alex Johnson's 1975 card, from his sloppily doctored uniform and cap to the background of blurry inconsequentiality to his expression of slightly bemused resignation, seems to sigh the words "just passin' through." Like Rudy May and Cecil Upshaw, Alex Johnson had come to the Yankees in the middle of the previous season, and, like his two just passin' through teammates, he'd move on to another team by the time the Yankees started winning pennants again. For the Yankees he'd make no impact, leave no mark. I wonder who will remember Alex Johnson. Though he won a batting title, in 1970, he may have been the most anonymous player ever to have done so. The year-by-year statistics on the back of his card show that batting title year as well as a handful of other good and even very good years, but they also reveal constant movement--two seasons with the Phillies, two with the Cardinals, two with the Reds, two with the Angels, one with the Indians, one season and most of the second with the Rangers, then 28 at-bats with the Yankees. After this card came out, he lasted one more season with the Yankees then spent his final year in Detroit. I envision baseball nostalgia as something like a baggage claim carousel. At the baggage claim carousel of baseball nostalgia for the years in which Alex Johnson was just passin' through, Phillies fans grab Johnny Callison, Cardinals fans snag Dal Maxvill, Reds fans snap up Vada Pinson, Angels fans corral Jim Fregosi, Indians fans and Rangers fans fight over Buddy Bell and Toby Harrah, Yankee fans deposit Bobby Bonds in the lost-and-found while looking for Bobby Murcer, and Tigers fans gleefully snare The Bird. Meanwhile, a sturdy, duct-taped, well-traveled Hefty bag keeps going round and round on the conveyer belt untouched. Who will claim Alex Johnson, right-handed line-drive-smasher-for-hire? Cecil Upshaw

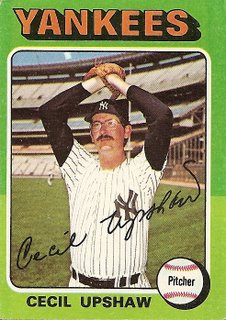

2007-02-17 09:44

As drink gave way to drink, the slow

Unfathomable voices of luncheon made A window of ultraviolet light in the mind, Through which one at last saw the skeleton Of everything . . . -- Denis Johnson, "The Veil"  When

last we left off, a drunkard suggested by the listing, woozy N on Rudy

May's cap had just had a door slammed in his face. Let's call this man

Mr. N. When

last we left off, a drunkard suggested by the listing, woozy N on Rudy

May's cap had just had a door slammed in his face. Let's call this man

Mr. N.Mr. N stares at the door that he once had a key for before the locks were changed. He sways a little. His face feels raw from shaving with cold water and a Bic in a gas station bathroom. He's still holding the decaying flowers up by his chest. He looks down at them and notices that he's buttoned his shirt wrong. His fingers are shaking. He can smell his own sweat. He starts thinking about where he can get a quart of vodka. He's looking down at the carpet the flowers will soon fall to. He says "please" one more time, but softly. Though I wasn't there to witness this moment, which I believe to have happened in 1975, I have decided that I know this man, having had repeated interactions with him years later, throughout the early- to mid-1990s. He was a man known to me and my fellow employees at 8th Street Wine and Liquor as Mr. Nikoff, so named by us for his consistent and prodigious consumption of Nikoff Vodka, the cheapest brand we sold in the liter and half-gallon size. He didn't seem to have very good hearing, but even so we didn't want him to know that he had been named after his booze. It's possible, though I can't recall for sure, that we referred to him at times as Mr. N for short and by way of a code while he was in the store. Through the doors of that store shuffled a steady string of the alcohol-destroyed, dirty-faced men who signaled their desire for a 9 A.M. half-pint of blackberry brandy or vodka with voices like metal scraping on stone, who paid with sticky, greasy nickels tapped out onto the counter from a styrofoam cup, who exited mumbling or cackling or cursing, who left livid ghosts of stink in their wake. But among this parade of ruination Mr. N stood out as the man who had not only fallen most completely into putrefaction but who had also fallen from the greatest height. Though you could barely understand what he was saying through his rotted teeth and tangled beard and through the tears in your own eyes that his piercingly awful stench produced, you knew that he was intelligent and educated, or he had been at one time. Sometimes all we could do after he staggered away with the help of a metal cane, his new liter of vodka secreted in his filthy trench coat, was repeatedly wave the door open and closed, spray the entire place with Lysol, breathe through our mouths, and gasp obscenities. But sometimes after all this we also wondered how he'd gotten to his current state. He knew arcane facts about the history of the labor movement, had informed opinions on the mayoral record of Abe Beame, lauded the abilities of the Gashouse Gang, seemed at times to speak with the trace of an English accent, even hinted once or twice that he'd been involved in some significant way with the University of Chicago. And he smelled like the aftermath of a funeral home fire extinguished with urine. And his fingers shook so badly that even on the days when he said nothing it took him several minutes to complete a transaction that took even our second-most ruined client a half a minute at most. For the last few days I have been thinking about Mr. N as I knew him and Mr. N as I imagine him as a younger man, outside the slammed door of his former one and only. With the help of this 1975 Cecil Upshaw card, which I have been looking at for days, studying it on the commuter train to work, on my lunch breaks, on the train ride back home, and during commercial breaks in my evening ingestions of foodstuff and television, I have also begun trying to imagine Mr. N's last perfect moment, long before I ever knew him but not that long before he stood staring down at the hallway carpet holding flowers and whispering the word please. If I was a religious person, I might define a perfect moment as one in which the individual is in total harmony with the divine. So let's say the Cardboard Gods comprise my religion. Let's say this photograph of Cecil Upshaw was taken before the doctoring of Rudy May's card from the same year, and let's say the much more graceful N and the Y on Cecil Upshaw's dark cap are Mr. N and his beloved dancing together in an unlit room in the middle of the night. It's a few weeks before Mr. N will have the door slammed in his face. The room is not lit because earlier that day the electric company shut off the power. Mr. N's beloved was first to discover that the electricity had been shut off and she took the flicking of the impotent light switch as a sign, even decided that she would end things with Mr. N, that it was just too hard, that it seemed too often that she was carrying him, dragging him, rather than that they were walking together. But he had come home that day with news of a new job, only temporary but with possibilities to become more than that. He was substitute teaching, a high school English class, and the regular teacher would be out for a while, so he would, he explained with his contagious excitement, not merely be babysitting but would actually be teaching great books. Mr. N's beloved, who had earlier resolved to tell him it was over, softened not at the news that he would finally once again have an income but with the light in his eyes, the optimism, the hope. Before long he would be discovered at the school with alcohol on his breath and be dismissed. He just had a little, he explained to his beloved, to calm his nerves before facing those animals. I can't, Mr. N's beloved said to herself. I just can't anymore. But before that there was this one perfect night, when both of them believed for the last time in a future together, and so their dark room changed from a curse to a blessing, for it showed that the light in the world came from the two of them together, dancing, in love, not even any music, and fuck everything else. In a perfect moment you won't even know the divine except to sense that beneath you and above you and all around you is an invisible world of infinite wonder and absurdity. You won't know the pinched bespectacled expression of the fading god of decent to mediocre relief pitching below you, nor the harmonious union of his tired arms above you in a gesture that paradoxically seems at once one of victory and surrender. You will not know that the intimations of triumph embedded in the uniform he wears will elude him, his time with the most successful branch of the Cardboard Gods brief and forgettable, nor will you know that the enmity-provoking aspects of this uniform are at this time dormant, the Yankees just another team to any creator of the divine under the age of 11 in 1975, your moment bathed in an innocence before hate. You will sense that there are worlds within worlds, that everything is connected and so everything is divine, but you won't know the particulars, such as, as the back of this Cecil Upshaw card states, the faltering pitcher pictured here, who will pitch just one more year, and not for the team named in this card, is the cousin of another faltering pitcher, George Stone, who is also on the cusp of his last go-round. You won't know that Cecil Upshaw came to the Yankees for, among others, the visionary alternative marriage experimenter Fritz Peterson, nor that Cecil Upshaw would leave the Yankees in a straight-up one-for-one trade for the most inspiringly accessible Cardboard God of them all, Eddie Leon. Or maybe you will know, but it will be beyond words. Beyond saving. As Denis Johnson puts it in "The Veil": . . . you'd know. You would know goddamn it. And never be able to say. Rudy May

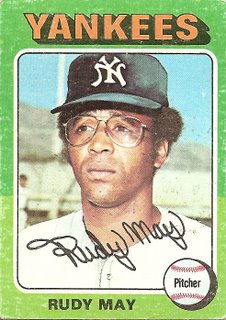

2007-02-14 06:19

Like

Bobby Murcer, Rudy May had two tours of duty with the Yankees that

lucklessly came just before and just after the team's 1977 and 1978

World Series triumphs. This perplexing card signals Rudy May's initial

arrival in New York, though it actually came out after he'd already

played half a season for the Yankees. The fact that he'd already

appeared in games with the Yankees, wearing a real Yankee uniform and a

real Yankee cap, makes it difficult to understand why Topps had to

resort to what may be the poorest bit of card doctoring I've ever seen.

The uniform shirt looks like a piece of college-ruled notebook paper

that sat out in the Topps parking lot all through a snowy winter and

sun-drenched spring, and the interlocking NY on the cap appears to have

been rendered by a distracted gorilla brandishing a tube of Crest

toothpaste. The N in particular seems to have a sordid, malodorous life

all its own, the part of the letter on our left like the staggering

in-buckling leg of a drunkard, the letter-ending flourish on the right

like the drunkard's wilted flowers, offered in an ill-fated attempt to

gain reentry to the apartment of his beleaguered erstwhile mate who

hurled him out onto the street after ten or twelve too many

booze-related fuckups. Like

Bobby Murcer, Rudy May had two tours of duty with the Yankees that

lucklessly came just before and just after the team's 1977 and 1978

World Series triumphs. This perplexing card signals Rudy May's initial

arrival in New York, though it actually came out after he'd already

played half a season for the Yankees. The fact that he'd already

appeared in games with the Yankees, wearing a real Yankee uniform and a

real Yankee cap, makes it difficult to understand why Topps had to

resort to what may be the poorest bit of card doctoring I've ever seen.

The uniform shirt looks like a piece of college-ruled notebook paper

that sat out in the Topps parking lot all through a snowy winter and

sun-drenched spring, and the interlocking NY on the cap appears to have

been rendered by a distracted gorilla brandishing a tube of Crest

toothpaste. The N in particular seems to have a sordid, malodorous life

all its own, the part of the letter on our left like the staggering

in-buckling leg of a drunkard, the letter-ending flourish on the right

like the drunkard's wilted flowers, offered in an ill-fated attempt to

gain reentry to the apartment of his beleaguered erstwhile mate who

hurled him out onto the street after ten or twelve too many

booze-related fuckups."Puh-pleaz . . . sweedard," the drunken N begs, wheezing, his drooping crocuses clutched to his chest. "I. I loveyou and. And I can change. I swear. I . . . I broughtcha these . . . Honey?" Slam. (Happy Valentine's Day, everybody!)

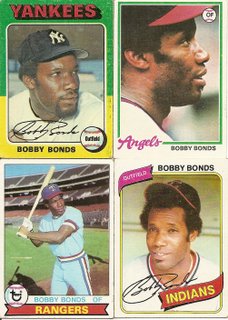

Bobby Bonds

2007-02-13 09:17

"For six long years I've been in trouble "For six long years I've been in troubleNo pleasure here on earth I've found For in this world I'm bound to travel I have no friends to help me now" -- "Man of Constant Sorrow" (traditional) On October 22, 1974, the San Francisco Giants sent the greatest of all the Next Willie Mayses to the New York Yankees for the greatest of all the Next Mickey Mantles. Beyond being perhaps the most even high-profile trade in baseball history (the players involved have been ranked by Bill James as the 15th and 17th best players ever to play their position), it also put an end once and for all to the hopes of each team's hometown fans that the hype might actually come true. Most overinflated expectations of this kind fizzle quickly, laughably, but in each of these cases they had persisted for years, their lofty realization seeming many times to be just around the next bend. Each player kept verging on greatness. The greatest of all the Next Willie Mayses was fast and strong, the most exciting mix of power and speed to come into the game since the First Willie Mays, and the graceful, explosive batting swing of the greatest of all the Next Mickey Mantles made it too easy to dream that the Mick had yet to limp off the field for the last time. But by 1974, with neither team winning, I guess each franchise just decided they had waited long enough for immortal lightning to strike twice. The trade broke the spell. Though Bobby Murcer and Bobby Bonds both continued to be among the best players in the game for a few more years, nobody persisted in thinking they were on the brink of becoming iconic, inimitable superstars. Murcer's post-trade career had a slight air of ennobled melancholy to it, Murcer the Yankee-at-heart in cold, windy exile in San Francisco and Chicago, Murcer the aging part-time slugger returning home to the Yankees in 1979, once again too late for a recent string of championships, just as he had been when his first tour with the Yankees had begun in 1965. As for Bobby Bonds, his post-trade career can be summarized by the collage of cards shown here. In this world he's bound to travel. He lasted in New York for one season, many Yankee fans belittling him not because he wasn't Willie Mays but because he wasn't Bobby Murcer. In 1975 he was traded to the California Angels, who then traded him to the Chicago White Sox, who then traded him to the Texas Rangers, who then traded him to the Cleveland Indians, who then traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals, who released him, allowing him to sign with the Texas Rangers, who then sold him to the Chicago Cubs, who released him, which allowed him to sign with the New York Yankees, who released him a month later, on July 21, 1982, without using him once, the wayfaring slugger's ninth and last major upheaval in seven and a half years since the sad and beautiful trade of the two Almost Greats. Bobby Murcer

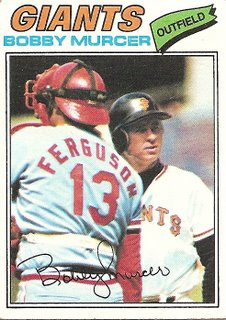

2007-02-12 13:41

I

was working a full-time job last year when I decided to cut back on my

hours. I wanted to spend more time on my writing. Since then I have

tried unsuccessfully to sell a novel that I spent the last several

years writing (and not writing). I have tried to find an agent for the

book by utilizing a small list of personal connections. So far the

agents I have contacted have said thanks but no thanks. I am now going

to send it out to 20 people whose names I will pick out of listings in

a book I bought at a Barnes and Noble. The way I feel about the novel

right now, it seems as if I'm about to send 20 people a manilla

envelope full of dried rabbit turds. It is a slow jerky trip to

nowhere, my supposed book. It is a pretentious and flimsy shield

against life and death. But what the fuck, I might as well go take a

trip to the post office and send out 20 copies of my novel to a bunch

of assholes who I will surely come to bitterly hate soon enough. It

will get me out of the house at least. I

was working a full-time job last year when I decided to cut back on my

hours. I wanted to spend more time on my writing. Since then I have

tried unsuccessfully to sell a novel that I spent the last several

years writing (and not writing). I have tried to find an agent for the

book by utilizing a small list of personal connections. So far the

agents I have contacted have said thanks but no thanks. I am now going

to send it out to 20 people whose names I will pick out of listings in

a book I bought at a Barnes and Noble. The way I feel about the novel

right now, it seems as if I'm about to send 20 people a manilla

envelope full of dried rabbit turds. It is a slow jerky trip to

nowhere, my supposed book. It is a pretentious and flimsy shield

against life and death. But what the fuck, I might as well go take a

trip to the post office and send out 20 copies of my novel to a bunch

of assholes who I will surely come to bitterly hate soon enough. It

will get me out of the house at least.Meanwhile, as I lose money on a weekly basis by not working full time the only writing I have been able to do has been about these fucking baseball cards I grew up with. And lately I have only barely been able to do that. Some people build houses or feed the hungry. I spend days on end trying to say something meaningful about Toby Harrah. Who the fuck cares? Yesterday when my wife was done studying for her grad school classes in social work we went to a bar for some dinner and we started talking about how we have to move out of our shitty apartment when the lease is up. There aren't any apartments out there anymore. Everything is now condos that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and are the size of a van. Maybe we can find some shithole to rent for a lot of money. Cross your fingers! We will have to find something. I started thinking about going back full-time to my job. It's not a bad job. I've certainly had worse. But the thought of going back while still a failure as a writer made me want to take the glass of beer in my hand and smash it into my forehead. (Employer: this is a completely fictional first-person narrative. Its author is excited about the prospect of expanding his role in the organization.) Our food came. We ate it and talked and drank our beers. My wife calmed me down a little. Eventually my urge to smash a glass of beer against my forehead lessened slightly. Anyway, today I got up and for fucking six hours I have been trying and failing to write about Bobby Murcer. I tried writing about the odd picture on this card, an opposing player taking up more of the picture than Murcer. I played a couple hands of solitaire, you know, to "loosen up." I wandered around on the Internet and discovered that this photo must have been taken during the second game of a doubleheader on July 18, 1976, because that is the only time Joe Ferguson caught for the St. Louis Cardinals in a road game against the San Franscisco Giants. I also found out that on that very same day, at the 1976 Summer Olympics, Nadia Comaneci's performance on the uneven bars garnered the very first perfect 10 ever awarded. I tried to write about perfection but the writing was atrocious. I took a break and ate a sandwich. Halfway through the sandwich I took a digital photo of our cats, who were lying together in a cute way on the couch. While finishing up the sandwich I bit my tongue pretty badly and stomped around for a few moments feeling sorry for myself. I went to the bathroom and stuck my tongue out at my reflection. My tongue was bleeding a little. Why me? Then I went back to the computer and tried again to write about Bobby Murcer, who seems to strike most people as a very nice man. I got nowhere. Anyway, here's the deal: Bobby Murcer is currently receiving chemotherapy after having a malignant tumor removed from his brain. He found out about the tumor this past Christmas Eve after going to the hospital for a bad headache. He is hoping to be in the broadcast booth by opening day. I'm rooting for him. I don't know what else to say. I can't imagine what it must be like to be in his shoes. I'm sure I would be cowering. Bobby Murcer seems to be facing the facts bravely. So here I am, several hours after the cold day began, still with nothing of any shape. Another unpaid day down the tubes. Everyone always says to not waste your life. Don't waste your life! You never know when it could all end! That type of shit. A headache could be a tumor. Live each day to the fullest! What the fuck does that mean? I don't know how not to waste my life. Anyway I'm calling it quits on this Bobby Murcer entry. I already deleted pages of shitty writing on Bobby Murcer and I am tempted to do it again but instead I'm going to say here I am in all my ugliness. Maybe that's better than hiding, maybe it's just as useless. Probably what I should have done is just wish Bobby Murcer well. If it's not too late that's what I want to do. I am rooting for him. I don't know how to do much but I do know how to do that, to root for somebody. Kick some ass, Bobby Murcer. This strange Joe-Ferguson-clogged 1977 card aside, the Bobby Murcer cards of my childhood always seemed to be festooned with the exciting "N.L. ALL STAR" insignia. For that reason I always have and always will think of Bobby Murcer as a star. U.L. Washington

2007-02-08 05:59

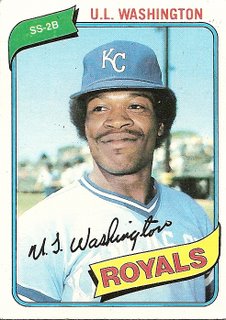

At

the time Ozzie Smith and Garry Templeton were exchanging teams and

destinies, I was probably more aware of a third young speedy promising

African American switch-hitting shortstop, U.L. Washington. This

idiosyncratic focus stems partly from the fact that I didn't know as

much about the National League in general, especially the teams

(besides the Joe Torre Mets) that never got into the playoffs, such as

the Cardinals and Padres. By the same token (whatever that means), I

knew U.L. Washington in part because his team practically lived in the

playoffs, but also because his name was U.L. Washington and U.L. stood

for U.L. Of course, the main reason U.L. Washington had imprinted his

name and image on my adolescent mind was that U.L. Washington played

every inning while chewing on a toothpick. At

the time Ozzie Smith and Garry Templeton were exchanging teams and

destinies, I was probably more aware of a third young speedy promising

African American switch-hitting shortstop, U.L. Washington. This

idiosyncratic focus stems partly from the fact that I didn't know as

much about the National League in general, especially the teams

(besides the Joe Torre Mets) that never got into the playoffs, such as

the Cardinals and Padres. By the same token (whatever that means), I

knew U.L. Washington in part because his team practically lived in the

playoffs, but also because his name was U.L. Washington and U.L. stood

for U.L. Of course, the main reason U.L. Washington had imprinted his

name and image on my adolescent mind was that U.L. Washington played

every inning while chewing on a toothpick.A

major leaguer playing baseball with a toothpick in his mouth is just

the kind of thing that fascinates a child. At least this child. And

since I was edging my way out of childhood when he came along, U.L.

Washington seemed something like a parting gift from the Cardboard Gods

to me, the last miniature Krackle bar at the last house the last time

trick-or-treating. Fittingly enough, I took my last candy-gathering

round as a 12-year-old wearing the laziest of all costumes, a sheet

with eyeholes, in 1980, just a couple weeks after watching U.L.

Washington gnaw on his toothpick while playing in the World Series. I

liked him instantly and rooted for him and, like thousands of other

American boys, I walked around with a toothpick in my mouth for a

little while. Unlike his two young speedy promising

African American switch-hitting shortstop National League counterparts,

U.L. Washington was not traded in his early years. I'm not sure who he

could have been traded for, since there weren't any other young speedy

promising African American switch-hitting shortstops in the American

League. Maybe the Royals could have worked out a deal with the Toronto

Blue Jays for switch-hitting shortstop Alfredo Griffin (who was not

African American but who was a young switch-hitting shortstop and who

more importantly would have enabled the Kansas City newspaper to print

the headline "Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Griffin!") with weak-hitting

Danny Ainge as a throw-in who would in turn bring them speedy African

American Terry Duerod from the Celtics. When, four years after the

Ozzie Smith-Garry Templeton trade, U.L. Washington finally did make his

debut on the transaction page, he was swapped for a 27-year-old

pitcher, Mike Kinnunen, whose sole brief and ineffective stint in the

majors to that point had occurred back when Garry Templeton was still

an All-Star for the Cardinals. U.L. Washington was in decline by then,

but even so, the question must be asked: Mike Kinnunen? It seems an

unnecessarily cruel mirror to hold up to the fading toothpick-gnawing

infielder who'd brought so much joy to the youth of America. The

Royals, who never once made use of Mike Kinnunen nor ever made it back

to the playoffs after parting with U.L. Washington, should be ashamed

of themselves, but not as ashamed as the Topps baseball card company

should be for this blatantly toothpickless photo. It's like depicting

Paul Bunyan without an axe.

Garry Templeton

2007-02-06 07:28

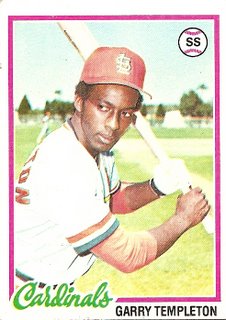

The

aesthetically pleasing evenness and soothing inconsequentiality of the

Toby Harrah for Buddy Bell trade seemed at first to also grace the 1981

swap of two talented young shortstops by teams that had, like the

Indians and Rangers, passed through the 1970s in various stages of

obscure ineptitude. The more well known of the two budding stars was

Garry Templeton, shown here in 1978 just after a spectacular first

season as a major league regular in which he hit .322 with 200 hits, 18

triples, and 28 stolen bases. He was only 22 years old when this photo

was snapped, and he seemed among the most promising young players in

all of baseball. In 1978 he slid back a little, hitting .280, which was

still better than most shortstops in the league, then in 1979 and 1980

racked up two more .300-plus seasons while lashing doubles and triples

all over the Busch Stadium carpet. Though he averaged over 30 errors a

season, he had good range and was considered among the better defensive

shortstops in the game. By the end of the 1981 season he owned a .305

lifetime batting average. You'd need only one hand to count the number

of Hall of Fame shortstops with a better mark. The

aesthetically pleasing evenness and soothing inconsequentiality of the

Toby Harrah for Buddy Bell trade seemed at first to also grace the 1981

swap of two talented young shortstops by teams that had, like the

Indians and Rangers, passed through the 1970s in various stages of

obscure ineptitude. The more well known of the two budding stars was

Garry Templeton, shown here in 1978 just after a spectacular first

season as a major league regular in which he hit .322 with 200 hits, 18

triples, and 28 stolen bases. He was only 22 years old when this photo

was snapped, and he seemed among the most promising young players in

all of baseball. In 1978 he slid back a little, hitting .280, which was

still better than most shortstops in the league, then in 1979 and 1980

racked up two more .300-plus seasons while lashing doubles and triples

all over the Busch Stadium carpet. Though he averaged over 30 errors a

season, he had good range and was considered among the better defensive

shortstops in the game. By the end of the 1981 season he owned a .305

lifetime batting average. You'd need only one hand to count the number

of Hall of Fame shortstops with a better mark.In

December 1981 Templeton was traded for a light-hitting San Diego Padre

shortstop who had just won his second consecutive Gold Glove. Though

several other players were thrown into the deal, perhaps foreshadowing

that the transaction would not work out as cleanly as the perfect

Harrah-Bell trade, the trade boiled down to what seemed to be a classic

exchange of young talent for young talent, on one hand the National

League's best-hitting shortstop, on the other the National League's

best-fielding shortstop. I wasn't monitoring reaction to the trade at

the time or anything, but I suspect that the apparently abundant gifts

of both players removed the possibility of a great outcry from either

team's followers. I would also guess that if there had been a poll

taken asking which of the players involved in the trade would someday

end up in the Hall of Fame, the majority would have gone with Garry

Templeton, whose lifetime batting average was at that moment over 70

points higher than his counterpart's. This is not a

Bostockian or Richardian tragedy, for Garry Templeton went on to play

for 16 major league seasons in all, and he was a member of the Padres

first-ever pennant winner in 1984. But after being traded to the

Padres, he never batted .300 again, never gathered more than 154 hits

in a season again, never reached double figures in triples again, and

only once hit as many as 30 doubles. Meanwhile, the player he was

traded for not only continued playing the best defense ever played at

baseball's most important defensive position, racking up 13 consecutive

Gold Glove awards in all, he also eventually became a more useful

offensive player than Garry Templeton. His Cardinals won the World

Series in his first year on the team (or, to put it another way, in

Garry Templeton's first year off the team) and would soon win two more

National League pennants. Throughout a 19-year career of consistently

astonishing glovework, Templeton's beloved and unassumingly charismatic

counterpart became famous even to non-baseball fans for the joyous

cartwheel-into-a-back-flip he performed on the way to his position in

the first inning of Cardinals home games. I don't know exactly how

Garry Templeton took the field in the first inning of games at his home

stadium, but I'm pretty sure he didn't do a cartwheel-into-a-back-flip.

I like to imagine that at some point during the twilight years of his

career Garry Templeton began games by loping onto the field and then

dropping arthritically to the ground near the pitcher's rosin bag to do

a slow, lopsided somersault. But he probably just jogged out there like

everybody else. Anyway, whatever he did, after a while nobody really

paid attention, except for the occasional prick who pointed at him, as

I am doing now, and said, "Hey, there's Garry Templeton. He was once

traded for the Wizard of Oz."

Toby Harrah

2007-02-05 09:47

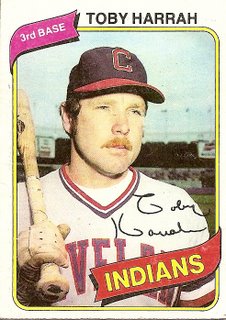

Nobody

ever discusses the most equal trades of all time. Conversely, the awful

trades come up periodically: Jeff Bagwell for Larry Andersen, Nolan

Ryan for Jim Fregosi, Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas, Derek Lowe and

Jason Varitek for Heathcliff Slocumb, Sparky Lyle for Danny Cater (and

a player to be named later, Mario Guerrero, who evened out the deal a

little, at least to me), Lou Brock for Ernie Broglio, Babe Ruth for No No Nanette.

I guess the even trades seem to have a way of dissolving in collective

memory. No scars are produced. I could only think of one equal trade

without Googling "equal trades" and "baseball," a search which turned

up even less than the trade I'd thought of on my own the moment I

looked at this card: Toby Harrah for Buddy Bell. No minor league

throw-ins, no cash, no players to be named later. One guy for another

guy. Perfect. Nobody

ever discusses the most equal trades of all time. Conversely, the awful

trades come up periodically: Jeff Bagwell for Larry Andersen, Nolan

Ryan for Jim Fregosi, Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas, Derek Lowe and

Jason Varitek for Heathcliff Slocumb, Sparky Lyle for Danny Cater (and

a player to be named later, Mario Guerrero, who evened out the deal a

little, at least to me), Lou Brock for Ernie Broglio, Babe Ruth for No No Nanette.

I guess the even trades seem to have a way of dissolving in collective

memory. No scars are produced. I could only think of one equal trade

without Googling "equal trades" and "baseball," a search which turned

up even less than the trade I'd thought of on my own the moment I

looked at this card: Toby Harrah for Buddy Bell. No minor league

throw-ins, no cash, no players to be named later. One guy for another

guy. Perfect.In retrospect, some might be tempted to give an edge in the trade to the Texas Rangers, who received Bell from the Indians while parting with Harrah. In most expert opinions, Bell seems to rank a few guys ahead of Harrah on the list of all-time best third basemen. In the 2001 edition of his Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James ranked Bell 19th and Harrah 32nd. Though I'm not qualified to argue with Bill James about anything even remotely connected with baseball, I still am tempted to stick up for Toby Harrah a little on the basis that Harrah matched Bell in the ability to drive in runs and surpassed him in the ability to get on base and, once on base, advance. He had good power, good speed, he drew a lot of walks, and he is probably the best palindrome-surnamed baseballer of all time. Also, a recent study by Baseball Prospectus revealed him to be, statistically speaking, the second-best clutch hitter of the last 35 years (behind Mark Grace). Bell's career lasted a little longer than Harrah's, and he also was one of the all-time best defensive third basemen, whereas Harrah in the field was merely like he was at every other aspect of the game: pretty good. James mentions how nice a guy Bell was several times throughout his book, so maybe that helped Bell move up a little versus Harrah in his estimation, especially considering that his entry on Harrah consists of an anecdote about how as a very young player Harrah was among those on the Washington Senators secretly lobbying for a mutiny on manager Ted Williams. But anyway, as trades went, the 1978 exchange of Bell and Harrah struck me at the time as perfectly balanced, and I still see it that way, each team getting a good but not great third baseman in his prime. Beyond that, the trade seems perfect to me because of the teams involved. The players changed teams but nothing really changed, good or bad, not for the Rangers, nor the Indians, nor Harrah, nor Bell. First place remained a rumor, decent personal statistics were compiled, empty seats bore witness, and history continued to unfold elsewhere. |