|

Monthly archives: September 2008

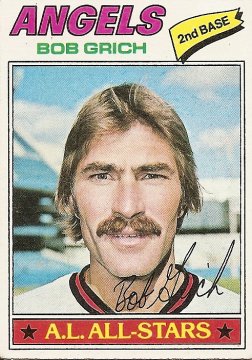

Bob Grich

2008-09-30 06:07

Baseball cards and comic books. Those were the two imaginary-world pillars that my inward childhood was built on. The two worlds come together here in this 1977 Bob Grich card, which always has and always will remind me of Marvel comics artist Jack "King" Kirby’s lantern-jawed, dimple-chinned heroes, who often paused amid dire intergalactic battle to fill the entire comic frame with their chiseled heads and deliver clear-eyed pronouncements of urgent courageous purpose, just as Bob Grich seems to be doing now. Most baseball cards imply that the next moment beyond the moment of the photo will be a few batting cage swings or a saunter to the outfield to snag some flies. But here it seems more likely that Bob Grich—as soon as he is done uttering something along the lines of "He has gone mad with power and MUST BE STOPPED!"—will in the next rectangular frame chronicling his adventures leap high into the sky on superpowered legs to collide jarringly with a dark muscular otherworldly destroyer with dead eyes and ornate Aztec-inspired headgear. As far as I know Bob Grich never tangled with Galactus or Modok or The Red Skull or even, I don’t know, chin music enthusiast of the Cardboard God era, Ed Farmer. I think Grich did once scream at Earl Weaver for pinch-hitting for him too often when he was a rookie, but no blows were thrown by either man. Instead, Grich just fairly quietly went about his job, over the course of his career creating a body of work bettered by only a couple handfulls of second basemen in major league history (Bill James, a longtime advocate of the underrated Grich’s estimable worth, ranked Grich as the 12th-best second baseman of all-time). This card heralded the beginning of Grich’s stay with the Angels. Interestingly, I have no memories of Grich beside this card until a moment at the very end of his Angels sojourn, which also happened to be the end of his career. The reason the latter moment, which came during the Angels’ 1986 American League championship series against the Red Sox, stands out in my memory is that once again Bob Grich seemed like a character who’d be at home in the pages of a superhero comic. I don’t recall exactly when the moment occurred, but it was either after the Angels’ third win, which put them up three games to one, or after the Angels took a commanding lead in the next game. The California sun was shining down, the home fans were screaming joyously, and Grich leapt into the air to give a seismic high five with a teammate, who in my memory was the Angel with the bulging comic book musculature, Brian Downing. Both Angels, but especially Grich, seemed larger than life, as if with a couple uncanny Hulk-like leaps he could bound all the way across the continent to New York to finally participate in his first World Series. He shrank back down to human size soon enough, I guess. In fact, I don’t remember seeing him during the Angels’ ensuing collapse. He became like the rest of us once again, who are only ever superpowered in our dreams. Steve Ontiveros and Doug Capilla

2008-09-26 07:04

One Continuous Mistake: The Cardboard Gods Story (So Far) The Cubs’ Gehrig-Ruth combo in nostrilness, shown above, came together in midseason with the acquisition of Doug Capilla, who became to the pitching staff what Steve Ontiveros had already been to the everyday players: someone capable of moving staggering quantities of oxygen and carbon dioxide, respectively, into and out of his nose. Cubs management may have been motivated to make the move by the strong play in the 1979 season of the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose alert, inspired, electrifying play and ebullient disco-laced camaraderie have been associated with and even partially explained by their ingestion via nasal canals of prodigious amounts of cocaine; Cubs brass may have reasoned that to compete with the Pirates they needed to get more "oomph" running through the bloodlines of their sluggish, lackluster squad, and saw the giant-nostrilled Doug Capilla as the means to this end. It’s not enough for me to end here, however, with this tribute to one of history’s forgotten collective achievements. I find myself wondering about Steve Ontiveros, who is like a forgotten entity within a forgotten entity. Not only is the 1979 Cubs’ nostril record uncelebrated, but the man who laid the foundation for the record, who brought his sizable nostrils to the ballyard every day, was likely cast aside by the Windy City's top nostril groupies as soon as the massive twin circular canyons in the middle of Doug Capilla’s face hit town. Worse, once Capilla took center stage on the team, Ontiveros became expendable, playing 31 games the following season before being released on June 24. He did not play major league baseball again. But in 1985 Steve Ontiveros debuted as an Oakland A’s reliever, only it wasn’t the Steve Ontiveros shown here. It was a different Steve Ontiveros. When you type the search terms "Steve Ontiveros" into Google, the first listing is for a page on baseball-reference.com. It is for the second Steve Ontiveros. In that way, the first Steve Ontiveros has been usurped once again, paved over by history. I’ve seen this kind of thing before while writing about my childhood baseball cards, seen guys named Dave Johnson and Dave Roberts dissolve into other guys named Dave Johnson and Dave Roberts. But, as names, Dave Johnson and Dave Roberts seem much more generic to me than Steve Ontiveros. I mean, I’ve lived a few decades and lived in two big cities and read a lot and I’ve never met or heard of anyone with Ontiveros as a last name. Are there two Kurt Bevacquas? Are there two Biff Pocorobas? Why must there be more than one Steve Ontiveros? I don’t know. But my disillusionment in this matter reminds me of when I was a kid and discovered that there was not just one Ray’s Pizza in New York but dozens of Ray’s Pizzas. This shook me up a little. Every summer, my brother and I would come down from Vermont and see our father in Manhattan, and our visit would always include at least one trip to Ray’s Pizza on Sixth Avenue and 11th Street, just a couple blocks from Dad's apartment. It was, I believed, the best pizza that has ever been made. As I remember it, there were times when the line for their giant cheesy slices was out onto the street, as if a piece of Ray’s was perpetually like a smash hit on Broadway. At some point, probably during solo visits from boarding school or college, when long pot-driven walks took me on my own through the city for the first time, I started seeing places that called themselves Ray’s Pizza everywhere. Worse, many of them claimed to be "The Famous Ray’s Pizza" or "The Original Ray’s Pizza" or even "The Famous Original Ray’s Pizza." Being that I was still the kind of neophyte pot enthusiast who "got the munchies" I occasionally found myself far from the village and hungry, and, feeling traitorous, I was forced to patronize some of these imposters, their uninspired triangular groupings of crust, sauce, and cheese always confirming my belief that there was only one Ray’s Pizza, and it was the one my father had taken me to. I of course don’t actually know which Ray’s Pizza came first; they don’t have their histories printed on handbills near the napkins and hot pepper shakers. But I know emotionally, and it galls me, a little. Why must there be more than one Ray’s Pizza? Which brings us back to Cardboard Gods. As I mentioned earlier in this series, I started Cardboard Gods a little over two years ago with some words on Mark Fidrych. Before that posting I had come up with the name and had typed the two words into Google to see if anyone else had beaten me to it. A handful of listings came up, but none of them had anything to do with baseball or baseball cards, so I had a name for my endeavor. If you type those two words into Google now you’ll find listings that differ quite a bit from the sparse listings I found back in the summer of 2006. I’m not encouraging anyone to perform such a search. Why would you? But if you do ever happen to find yourself wandering around and wondering about Cardboard Gods, I just wanted to get it down in writing that this is the original Cardboard Gods. The one that was here first. The one with the extra cheese. The one with the record-breaking nostrils. Rowland Office, 1976

2008-09-25 05:52

Part 2 of 3 (Continued from Skip Jutze, 1976) I have written about Rowland Office before. But since my shoebox at the time of that writing was sadly and mysteriously lacking a single Rowland Office card, I had to attach my thoughts on the subject to a 1975 Braves team card that included the young outfielder in miniature, sardine-canned in with the other dour blurry figures from that year’s forgettable Atlanta collective. Over a year after that posting, which attempted to describe the strange gleeful hold Rowland Office’s yearly appearances on baseball cards had on my brother and me, and to speculate why all the Rowland Office cards I was sure I had owned as a child had somehow vanished, a reader named Jeff Demerly contacted me and kindly offered to cure the inexplicable Office-less wound in my collection by sending me his double of the 1976 Rowland Office card, shown here. Skip Jutze, 1976

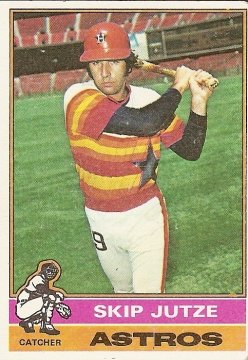

2008-09-23 09:45

One Continuous Mistake: The Cardboard Gods Story (So Far) Part 1 of 3 I. I have written about Skip Jutze before. But as sg schier pointed out in a May 30 comment attached to that first Skip Jutze post, I got it wrong. But how could I get it right? How could I ever hope to say all there is to say about Skip Jutze? And I feel that tingling, excited sensation again, the one I get when I know I’m about to get it wrong. It’s not a bad feeling. In fact, it makes me feel alive. I get it when I’m holding one of my baseball cards from my childhood and starting to glimpse the glittering possibilities embedded like a lode of diamonds all over in the card. It's like that Beatles song. It’s all too much for me to take. The love that’s shining all around you. I know I’ll get it wrong. I can’t possibly say it all. Skip Jutze! Here he is, a couple years before his appearance on the card I’ve already written about, younger than that doleful sky-gazing mustachioed journeyman on the Mariner card, the younger Skip Jutze looking directly into the camera with the adamantine confidence of an athlete who has been second to none for almost all of his life, a superstar in every sport he played, a hometown legend. The confident look prevails despite the data on the back of the card, the birth date acknowledging that he’ll be turning 30 in May, the .226 lifetime average, the lack of even a single career home run. The front of the card is no different: The lopsided layout cheapens what already must be a card nearly devoid of worth. The empty stands hint at Skip Jutze’s status as a guy to be gotten out of the way early by the Topps photographer, before the regulars swagger onto the field. The polyester rainbow of his uniform seems cheap and desperate, especially since the number on Skip Jutze’s pants, 9, does not match the number, 23, on the bottom of the bat in Skip Jutze’s hands. He is a spare part, just passing through, briefly flickering between the minors and the majors, tossed a leftover uniform and a random bat. And yet, taken all together, the confident look, the paltry stats, the garish uniform, above all the name, Skip Jutze, immune to renown, it all speaks to me not of failure or success but of something beyond that false duality, the sweet stinging tension of life itself, our moment alive, holding with all our might to might, to if, to maybe, to the brink of another bright uncertain day sparkling and sharp with the diamonds of possibilities and mistakes. "When we reflect on what we are doing in our everyday life, we are always ashamed of ourselves. One of my students wrote to me saying, ‘You sent me a calendar, and I am trying to follow the good mottoes which appear on every page. But the year has hardly begun, and already I have failed!’ Dogen-Zenji said, ‘Shoshaku jushaku.’ Shaku generally means ‘mistake’ or ‘wrong.’ Shoshaku jushaku means ‘to succeed wrong with wrong,’ or one continuous mistake. According to Dogen, one continuous mistake can also be Zen. A Zen master’s life could be said to be many years of shoshaku jushaku. This means so many years of one single-minded effort." – Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind I started Cardboard Gods a little over two years ago when I randomly grabbed from my shoebox full of aging cards my one and only Mark Fidrych card, an amazing stroke of luck considering the fact that there’s probably no other player who embodies for me the dreams and joys and disappointments of childhood and its endless shadow than the ebullient curly-haired nutjob rookie, the Bird, who ruled the American League for one slim beautiful year before breaking his wing and dropping almost instantly out of sight. Holding his card, I got that tingling, excited sensation. I was very glad to be feeling it. The worst thing in the world is if you start feeling like you’ve somehow got to a point in your life when you can’t make any more mistakes. For one reason or another you’ve marginalized yourself, removed yourself from the game. I had spent the previous years working on a novel and upon the messy uncertain completion of the book had been unable to publish it. I felt worn out, empty, demoralized, buried, removed. I needed to get back the feeling that I was still alive, that mistakes were still possible. Enter the Cardboard Gods. After only a week or so of profiles I found myself writing what seemed to be a particularly dull ode to Otto Velez. I wondered if things had run their course. For months after that I’d periodically circle around to that Otto Velez feeling. Certainly, on any rational level the whole project was ludicrous. OK, write a few things about your baseball cards and then move on with real life. But dedicate yourself to it indefinitely? I have been doing this for a couple of years and I have only covered a fairly small percentage of the baseball cards from my childhood. There are still so many mistakes to be made! I want to infect every card I own with my failings. I want to make a single-minded effort, one continuous mistake. I want to get every single Cardboard God wrong. (continued in Rowland Office, 1976) Jerry Augustine

2008-09-22 05:08

Chapter Six Like most of those visited by the Two Freaks, Augustine began drifting toward the margins in the aftermath of the visitation. He was still young in this 1980 card, still seemingly capable of becoming a notable figure in the baseball world. He hadn’t set the world on fire, but he’d had his moments, winning 13 games two years earlier and making a successful shift from the rotation to the bullpen one year earlier, with nine wins and five saves. But after the Two Freaks infused his card with hints of other, stranger worlds beneath this one, Jerry Augustine gradually drifted toward the fringes, as if following the hints. Appearances dwindled, earned run averages ballooned. Though still logging some innings here and there as a lefty reliever in both of the Brewers playoff seasons of 1981 and 1982, Augustine was never called on to pitch in the post-season in either year. He was granted free agency by the Brewers at the end of 1984, but no one picked him up. Phil Mankowski

2008-09-20 07:48

Chapter Five Johnny Sutton wasn’t the only figure featured in Topps’ notably drab 1979 series to receive a wadded-up handwritten message from the Two Freaks. Check the slight bulge—the exact size of a wadded-up page—in Phil Mankowski’s back pocket. Now check the troubled look on his face. While Johnny Sutton’s expression of 89% muted trepidation and 11% dim hope implies that the letter balled up in his glove was unread at the time of his photograph, the face of the player in the card shown here speaks of enigmatically haunting information freshly received. Phil Mankowski, who should be snarling with confidence, a young, promising player on a young, promising team, instead appears to be in the earliest stages of a comprehensive existential cringe, as if he has just been shown the few seasons of stats on the back of his baseball card in the context of a detailed timeline of the 4.54 billion year history of the planet. We don't amount to much. *** Dear Fellow Marginal, Before we embark on our urgent message to you, please allow us to introduce ourselves. We were born and one day will die. In between those two points there has been disappointment, but not nearly enough of it. Oh to be so disappointed that all points are dispersed, disassembled, dissolved, linear narrative forever undone. There is no story! There is only Right Now! But until that day we live in a hierarchical age where everyone is enslaved by the linear story that goes "we were born and one day will die," so to communicate we must temporarily conform and speak in those terms. We have been roaming the land for some years. Long ago, while taking our first awkward bony-kneed steps out of childhood, we were savagely beaten by a small informal collective of muscular peers from fractured, economically disadvantaged families. After that one of us developed a gift for silence, which was referred to by most as a stutter, while the other developed a gift for staying in the present, thought of by most as a damaged memory. At first we struggled with what we saw as our afflictions, seeing that they would make it difficult for us to live normal lives. At the same time, we kept our distance from one another, despite our history of being close childhood friends. We each saw the other as weak, a magnet for further victimization. Odd that we were brought together again by those supposed afflictions one day in the parking lot of our local military induction center. Instead of being shipped to a faraway land to kill and be killed, we were rejected for our afflictions. We laughed together in the parking lot, finally reunited, and wondered what to do with our ridiculous freedom. Roam the land, we decided. Roam the land and be as pointless as humanly possible, spread the garbled word as quietly as possible, so quietly it is only ever caught in a flicker, to seep past conscious thought, to be immune to memory, to exist only as a seed for dreams. We have been public figures with no publicity. We are the winners of the contest to see who can throw the softest punch. We are the sound of one hand clapping. We are the tree that falls in the forest with no one around to hear. Do we make a sound? The only way to know is to join us. This is our urgent request. In fact you already have joined us. Embrace your fate as one easily forgotten. Marginals of the World Unite! The epoch of chemically-aided hope that weirdness and wide open spaces might one day reign is nearing an end. The 1960s eructed Technicolor puke all over the 1970s but the puke has almost completely dried. It’s 1979. Everyone is depressed, divorced, precariously employed. What is the point of your meaningless flailing? There is no escape from this profound inconsequentiality. There is no escape from this brief gift. What to do with these entwined incarcerations. What to do in this life? We urge you, when next you are called upon to perform your duties, to refuse. Accompany the refusal with silence, or nod to our fictional forerunner, Bartleby, and say that you would prefer not to. We have contacted several just like you and implored them to do the same, to do nothing, to refuse. Think of the effect on the world! All us supposedly desperate ledge-clingers letting go of the ledge. Refusing to pinch-hit, refusing to mop up, refusing to act as a late-game defensive replacement in lopsided blowouts. If we marginals could all fall together the enslaving story that ends in death would be undone. When there is no up or down, falling becomes flying. Please do something senseless. Sincerely (And We Mean That), The Two Freaks *** Phil Mankowski did not, as far as I know, follow any of the garbled collective suggestions of the freak with the stutter or the freak with the faulty, clouded memory. He did, however, change upon the release of this card from a young, promising player with .275 career batting average (high for a third baseman of that era, especially compared to the anemic hitting totals produced by the aging Tigers regular at the position, Aurelio Rodriguez) into a prototypical major league marginal. After hitting .271, .276, and .275 in his first three seasons, Mankowski plummeted to .222 in 1979, causing the Tigers to paperclip him to a deal that sent journeyman Jerry Morales to the Mets for famed digger of graves Richie Hebner. Mankowski hit .167 in 12 at-bats in 1980, didn’t play in the majors in 1981, and called it a career with a .229 mark in 35 at-bats in 1982. Never much of a power hitter, he had managed a respectable 8 home runs in 593 at-bats prior to appearing on a baseball card with the letter from the Two Freaks in his back pocket. He would never go deep again. (to be continued) Technical Difficulties

2008-09-17 08:17

My Internet connection broke on Sunday and as yet is still broken. I've spent a lot of time on hold, listening to one endless instrumental song, staring out at a street devoid of repair vans, using all my might to restrain myself from smashing myself in the head. No Cardboard Gods until that situation is resolved (the Internet connection situation, that is, not the own-head-punching situation, which will probably take years of therapy or arm amputation to bring to a close). Johnny Sutton

2008-09-12 07:59

Chapter Four Contrary to what you might guess, a baseball is not hidden inside the glove of Johnny Sutton, but rather a crumpled wad of lined notebook paper the approximate size of a baseball. The wad struck Johnny Sutton in the head with a barely noticeable impact just moments before this off-center picture was taken. He was stepping across the foul line and felt something tap him. He picked it up and looked around but saw nothing. Whoever had tossed it at him had somehow almost instantly disappeared. Johnny Sutton noticed writing on the wad's inner folds but didn’t have time to open the wad before the photographer brusquely and distractedly waved him into position and snapped the photo with an apathy that would result in the finished product we see here: Greg Gross

2008-09-10 13:52

Chapter Three In the 1970s everyone looked toward the sky with amazement and consternation and wonder and fear. Nuclear bombs might fall any second, hangliders and hot-air balloonists might rise. One nut strung a tightrope across the World Trade Center buildings and did his highwire act up there, and a few years later another nut climbed up the side of one of those giant doomed towers. Jonathan Livingston Seagull ruled the bestseller list with its laxative-soft tale of a noncomformist bird who flew in odd ways, outside the flock, and later in the decade the author of that book further fattened his bank account with another enormous smash entitled Illusions, a pamphlet-thin tract about a magical guru who roamed from town to town giving enlightening platitude-heavy rides in his small magical propeller airplane. Oh to fly free and easy far above all the ungroovy problems of the earth! But how free and easy was it? Bald eagles grew scarce, their endangerment symbolic in the flagging Age of Malaise. Gunpoint skyjackings and fiery crashes made even larger claims on the public imagination than usual, as evidenced by the decade-long franchise of a particular wing of the then-booming disaster movie genre (Airport, Airport 1975, Airport ’77, and The Concorde . . . Airport ’79). Meanwhile Skylab was falling, big chunks of it raining down, the once-gleaming American space program impoverished and in shambles. The sky was full of danger! Even standing around outside gazing up at the thing might get you brained by shards of flaming metal. Greg Gross was not a guy you’d think of as being a sky-gazer. He was welded to earth, neither a guy who could “fly” on the basepaths (like two of the guys who kept him on the bench in his many years with the Phillies, Garry Maddox and Bake McBride) nor a guy (like the other fellow who kept Greg Gross on the bench, Greg Luzinski) who could hit “towering moonshots.” His combination of a complete lack of power and an utter lack of speed was as rare among outfielders then as it would be now. In seventeen seasons, he hit just seven home runs, but he erupted for five of them in the year just prior to this card. I imagine him allowing the keen focus that would allow him to compile a .287 lifetime average and a .372 lifetime on-base percentage to wander momentarily after that power barrage. Maybe I could become one of those guys, he thinks for a second. He holds a bat in his hands as he thinks this, imagining for one second that he might yet author majestic drive after majestic drive and thus become a creature not of the earth but of the lordly sky. But just as he thinks this the Two Freaks appear right in the center of his vision. That is to say they are flying. Or falling. It all happens very fast. There is always the whisper of doom around the Two Freaks, a sense somehow communicated even in glimpses that they can’t keep on doing what they are doing for very long. How will they eat? How will they pay the rent? For that matter how will any of us keep ourselves above the greedy pull of the ground? This all flashes past Greg Gross’s eyes in an instant to end his visions of a bevy of slugging percentage crowns. One of the Two Freaks, the curly-haired one seen elsewhere tooting a recorder, is pedaling an ungainly bicycle-powered contraption with wings, and the other, the thin longhaired one, is lashed to a giant yellow kite attached by thin string to the rear of the bike-plane. Flying? Falling? Hard to tell. It all happens so quickly. It always happens quickly. Greg Gross lasted 17 seasons as an earthbound hitter of singles. A long time as baseball careers go, but surely a blip in his mind by now. It all goes by quickly. It flies. Such was the case with each ambiguous and unsettling visitation by the Two Freaks. A blink of the eye, here then gone. This must have been by design, the two figures seeking to define their doomed and beautiful decade as if whispering inaudibly the curses and praise of an institutionalized angel. (to be continued) John Curtis

2008-09-08 13:37

Chapter Two The Two Freaks roamed the land. No one remembers them now. How could they? Even when they were around very few ever noticed them, and then only in fleeting glimpses that could easily be dismissed as a trick of the eye, a second glance always finding them gone. They stuck to the shadows, the margins, the fringes. Occasionally they showed up at gatherings, but only the sparsely-attended ones and only for a moment. There are no records that they ever existed, but if you ask me there are traces. Here, there, and everywhere: traces. Through all the years of my 1970s childhood, the Two Freaks roamed the land. They showed themselves to John Curtis just moments before this picture was snapped, though by the time his own less-elusive image was captured they were gone, leaving the bespectacled journeyman hurler to wonder if they’d ever been there at all. He’d been taking a pregame nap in the bullpen when summoned by the baseball card people, and while still half asleep, stumbling through the bullpen gate, he’d heard the thin flat tooting of a wooden wind instrument and saw whirling longhaired figures rushing by him, close. “Security!” someone had yelled. John Curtis had staggered backward, blinking, and when he’d regained his balance the blurry figures had disappeared. He continued walking until the photographer told him to stop, then performed his guarded, flat-smiling pose, the slight wince underlaying his facial expression hinting of his growing doubts about the whole strange encounter. "Say cheese," the Topps photographer said. "Just a synapse misfiring," reasoned the college-educated lefty to himself as he pretended to be ready, glove-up, to field a screaming liner through the box. "Got it. Beautiful. Couldn't have been better," the Topps photographer intoned, distractedly. He was already scanning his clipboard for the next forgettable 1976 Cardinal. "Just a trick of the mind," thought Curtis, meandering away. But as John Curtis moved back toward the bullpen to await a situation hopeless enough for his long-relieving services to be necessary, he noticed that what he’d already decided was a dream had somehow left some tangible residue. The sky clouded over and it started to rain, and John Curtis went to stick his pitching hand into his back pocket and jog for cover, but as he did so he found that a big red umbrella was jutting from the rear left compartment in his pants. He hadn’t put it there. Why would he? It had to have come to him from the Two Freaks. He pulled the umbrella from his pocket and opened it. The sudden shower beat down, making everyone else on the field scatter. John Curtis just stood there, laughing, temporarily invincible beneath the small yet inarguable miracle of shelter. (to be continued) Ken McMullen

2008-09-05 14:38

A perturbed Ken McMullen, fading holdover from an earlier, more cleancut era in baseball, has just noticed a couple of unusual figures in the stands. A couple of freaks. I can’t know this of course. All I can know is that Ken McMullen, at the time of this 1975 card, had been kicking around the league for twelve years. He started out with the Dodgers in 1962 but was traded to the second incarnation of the Washington Senators after three seasons and 311 at-bats. He had several productive years with that team, establishing himself, most likely (I’m too lazy too research it), as the greatest third baseman in the entire doomed and desultory eleven-season history of the second edition of the Washington Senators. The Senators shipped McMullen to the California Angels during the first season of the new decade, and in 1973 he came back to the Dodgers, the team of his early major league career and possibly the team of his youth, judging from the fact that he was born in Oxnard, CA, and was still calling it home at the time of this card, suggesting that he had lived there all along and so was there, an impressionable cleancut teen, when the Dodgers relocated from Brooklyn to nearby Los Angeles in 1957. The story told by this card, or by all of this card except the enigmatic expression of the player on its front, could be a comforting one, a story about coming home, the onetime Oxnard-born Dodger an Oxnard-based Dodger once more. Any conjecture about his sour, apprehensive expression, which sends a negating shiver through whatever comfort is offered by the circle-of-life place names on the back of the card, is beyond the borders of the card, and nothing can be affirmed with any certainty about matters that are beyond the borders of the card. But nothing can be ruled out, either. Anything is possible. So I’ll say it again, as if it were true, because it might be, and in my always-diminishing world might is just about the only right: Ken McMullen, aging holdover from an earlier, more cleancut era in baseball, has just noticed a couple of unusual figures in the stands. A couple of freaks. One of them, a bushy-haired guy with glasses, is playing the wooden, flute-like instrument known as the recorder. The other is of ambiguous gender and swaying back and forth, eyes closed, either mumbling valium-inspired nonsense or chanting. Ken McMullen can't make heads or tails of any of it. His world is changing all around him. Getting stranger, harder to understand, worse. He'll end his career not as a Dodger but far away, in Milwaukee. “Goddamnit, what the hell,” he is about to say. (to be continued) Mario Mendoza

2008-09-03 10:46

Chapter Five I. |