|

Monthly archives: July 2008

Johnnie LeMaster

2008-07-31 13:08

Below are a couple sketches of the obscurely infamous alter ego of the slight, scraggly, plainly obvious baseball imposter pictured here, from the classic but extremely difficult-to-find book I have excerpted from before here on Cardboard Gods, Dead on Arrival: The Oral History of Giant Prospects, the Greatest Punk Band No One Ever Heard Of: From page 134-5: Greg Johnston [bass]: Yeah, I guess because of that whole fake baseball card flyer thing, we started seeing people in ripped-up baseball shirts at our shows. It was right around when The Warriors came out, so maybe that helped add a kind of violent edge to it. You’d see these sketchy speed freak characters in their old little league jerseys and eyeblack, just itching to break a pool cue over somebody’s head. John Tamargo [aka Johnny Tomorrow, drums]: Joe [Strain, legendary frontman of Giant Prospects] hated those baseball fucks. He was starting to crack around then anyway, but that whole thing didn’t help. He’d stop songs in the middle to scream at them. Ned Alvin (club owner): It got ugly. He stopped right in the middle of the set and started lecturing them. He thought they were violent fascists. I don’t know about the fascist part but they were pretty violent—they’d pretty much cleared the floor of anyone not willing to have their head caved in by one of the souvenir mini bats they held in their fists as they flailed around to the music. Anyway, Strain kept calling them stormtroopers. They didn’t get the reference. I clearly remember one of them screaming back, “Fuck Star Wars!” Johnston: Finally one of them walks toward the stage, toward Joe. This skinny unshaven derelict in a jersey just like the ones we posed in for the flyer. He’s staring at Joe so insanely that Joe stops haranguing them and stares back. It’s a showdown! The guy grabs a bottle off a table. Joe grabs a bottle from the edge of the little stage and steps down. These two skinny nutjobs just stare at each other, both of them smiling, then finally the guy smacks the bottle against his own head, not breaking it. Joe does the same to his head. They both look kind of woozy but they do it again, whack! Whack! They’re trying to break the thing but they’re [laughs] they’re fucking complete weaklings! Even with all the speed coursing through them! Eventually the bouncer breaks it up, everyone in the place looking like they don’t know whether to laugh or puke. Weirdest fight I’ve ever seen. Anyway, that was how Joe Strain met Johnny Disaster. From page 137: Eddie Toth (band manager): Errors. That’s how I would characterize the Johnny Disaster era of Giant Prospects. Things probably wouldn’t have lasted much longer anyway. When Greg Johnston left the band [to take a job as a sous chef] he did so because he was the first to see that the ship was sinking. But Johnny Disaster didn’t exactly help slow that process. He just could not play bass. I mean, his whole thing was that he was bad at everything, that he was a failure. I’m sure that’s why Joe paired up with him. Joe was always going on and on about the “Redemption of Failing,” even before he met Johnny Disaster. Sometimes I wondered if Joe Strain had created Johnny Disaster. You know, like Frankenstein. His perfectly awful creation. Anyway, it made the shows into a comedy of errors. Make that a tragedy of errors. Tamargo: Thing I remember about Johnny Disaster is he had the word “BOO” tattooed on his chest in big block letters. He’d show it off when people started throwing things at the stage because we sucked so bad. From page 238: Johnston: Whatever happened to Johnny Disaster? Funny you ask. I ran into him not too long ago in an airport. I didn’t recognize him, but I guess he recognized me. He said he was on his way to San Francisco to take part in some Giants’ reunion. He’d completely lost it and thought that he’d actually been a baseball player! I was looking at this crazy glint in his eyes as he was telling me all the great teammates he’d had and I was wondering to myself, “How the hell did this guy get through security?” It has made me a little nervous about riding on airplanes, actually. Gaylord Perry

2008-07-29 11:30

In hopes of compensating for a recent summertime slowing of output here at Cardboard Gods, I offer this spectacular specimen, a card that has for some days now rendered me speechless with its boundless magnificence. Where do I start? Should I attempt to reconnect to that giddy feeling from childhood (long since faded as such things always do with the tendency to take things for granted) that derived from learning that there was a person, and not just any person but a major leaguer, and not just any major leaguer but a superstar, named Gaylord? Or should I try to start a discussion about cheating? Though it has quieted down a bit since last year’s revelation of The Mitchell Report and Barry Bonds’ breaking of the all-time home run record, the issue of cheating still seems to be one of the dominant themes in baseball today. Bonds can't get a job this year, even though he wants to play and surely can still hit better than all but a few people on earth. I suppose this is mostly due to teams not wanting the headache of the media circus sure to erupt upon Bonds’ arrival with the team. Part of that circus would certainly include the copious use of the word cheater. At the recent Hall of Fame induction ceremony, this issue was also present, in the form of an absence. By now, Mark McGwire’s prodigious numbers would have certainly gained him entry into the Hall of Fame, but it looks instead that he may never get in, voters unwilling to elect someone who is roundly assumed to have cheated by using performance enhancing drugs. The obvious hypocrisy that I’m driving at with all the finesse of a bulldozer is that in that very Hall of Fame is a plaque for the man pictured here, who rather openly admitted to cheating whenever possible. The thing is, while I see intellectually that this is a double standard, I feel on a gut level that I'm OK with this double standard. The baseball world at large seems to agree. I wonder why? Maybe it has to do with romance. Gaylord’s an Old West cardsharp, crafty and skillful. McGwire, Bonds, and Clemens, on the other hand (to name the three most prominent figures in the ongoing issue), seem to be greedy, inelegant brutes. How much skill does it take to jam a needle in your ass? And speaking of ass, we finally come to the subject I most want to address in terms of this card. The photo, which on first glance appears to be a great action shot of a crafty gray-haired veteran in the midst of a wily offering sure to reduce the batter to a frustrated obscenity-laden tirade, on closer look appears in fact to offer the secret to the hurler’s long-running and otherwise somewhat difficult-to-explain success. Please look closely, and without the prejudical knowledge of both baseball pitching mechanics and the usual placement of body appendages. Do you see what I see? That Gaylord Perry was able, with some exertion showing plainly on his well-lined face, to excrete, from his anus, a third hand. This would explain a lot, wouldn’t it? I mean, of all the many entertaining instances of a player getting caught red-handed (Joe Niekro trying to toss away a file as an umpire approached him on the mound, cork exploding from Sammy Sosa’s bat, etc.), the most notorious rule-stretcher of them all, Gaylord Perry, who even entitled his 1974 mid-career autobiography Me and the Spitter, eluded authorities for his first 21 years in the majors, not earning his first suspension for rule-bending until his second-to-last go-round in 1982. Everyone agreed he made baseballs do ungodly things. But how? Probably this card shows nothing but the fact that he had a way of keeping his right arm close to his side in the middle of his delivery to add to his prodigious arsenal of deceptions. But maybe it shows, like those rare photos of Bigfoot or Nessie, something more monstrous and wondrous. I mean, maybe, just maybe, we are glimpsing Gaylord Perry’s uncanny assball. Stan Thomas

2008-07-25 07:41

It’s still a few months away, but I’m already looking forward to my religion’s biggest holiday: Expansion Day. The truth is I just invented this holiday a few minutes ago, just as I have been for the last couple years on this site gradually and half-assedly inventing an indecipherable tangle of fallible deities and contradictory beliefs so as to, among other vague purposes, fill the decades-old irreligious void located roughly where I stuff all the potato chips and beer. (The gut thickens; the void remains.) Yesterday was one of those days that circle around inevitably to fall on me like a sour mist, depressing and slack for no apparent reason, boredom and uselessness attaining the level of a physical ache. I dropped into fantasies of contracting some sort of exotic incurable illness that would not kill me or even hurt that much but that would somehow make it necessary for me to spend the last several decades of life in or near a comfortable bed. There I would sleep a lot and watch episodes of old television shows too obscure to have ever been released on DVD but somehow made available to me by the powerful pity-charged network of affectionate well-wishing that added further cushioning to my stress-free invalid life. "How are you doing?" each visitor would say, smiling sadly, as he or she entered my room. "Oh," I’d say, adding a very slight wince to my brave smile. "I can’t complain." "You’re so brave," the loving visitor would say. "And hey, I brought you a bootleg video of all eight episodes of Quark." As fantasies go, it’s probably not as alarming as, say, fantasizing about going one step further and offing oneself, but it’s not exactly a sign of robust mental and spiritual well-being. I mean, consider that oft-mentioned and supposedly motivational notion of a deathbed, as in "When you are on your deathbed, how are you going to look back on your life?" (It’s supposed to inspire you to seize the day, I guess.) But in my fantasy, when I’m finally on my deathbed and looking back at my life, I’ll be looking back at a life spent on a deathbed. Which is a pretty narrow way to go through life. And so when things start to seem narrow, from now on, I will try to remember Expansion Day. As Expansion Day approaches I’ll have more to say about it, maybe, about what it means to me, about the rituals involved in such a day, about the many legends and miracles intertwined with that day, but for right now I will just pass along the date of this holy day, November 5, and take a stab at the core of its importance to me and my ridiculous religion: It is about possibilities. Lame as it is, there is a certain purity to my religion, in that I am its only adherent. This will always be the case, but if instead it followed the path of development of other religions fissures and splits would inevitably occur. Take Expansion Day. The cleancut, success-oriented BlueJayists would emphasize the day as one in which seeds of future glory were wisely planted, while the more fatalistic Marinerites would find complicated klezmeresque celebration among the inescapable solemnity of life. Joy in the tears. The list of names would be at issue, the Holy List of the Expanded, and among the names of the Blue Jays would be some, Whitt, Clancy, Iorg, who would one day rise up from the ignominy of being deemed unnecessary to appear in the miraculous baseball version of the afterlife called the postseason, whereas among the Mariners listed there seem to be only years of neither rising nor falling, none of the Holy Names ever offering any readily apparent deliverance. But still, even though you are marginal, unimportant, unprotected, cut loose, drifting, possibilities dwindling or gone, there is Expansion. You are chosen. Ken Reitz

2008-07-23 12:56

When I was a kid, I was fascinated by what I thought was the nickname of the man shown here making one of his frequent outs (this particular out perhaps stemming from his failure to don the batting glove sticking out of his back pocket, or perhaps due to a batting grip seemingly modeled on a tableside waiter grinding a pepper mill): I remember Ken Reitz’s nickname as being The Big Zamboni. I don’t know where I got that idea. Maybe it’s on the back of another of my Ken Reitz baseball cards. More likely I made it up by somehow combining the actual nickname for Reitz listed on Baseball-Reference.com, Zamboni, with the nickname of the song-and-dance-prone Laverne and Shirley character, Carmine “The Big Ragu” Ragusa, whose name sounds like the ace of the post-Tatum O’Neal Bad News Bears, Carmen Ronzonni, whose last name sort of sounds like Zamboni. I’m pretty sure that when I did get it in my head that Ken Reitz was The Big Zamboni I didn’t know what a Zamboni was, but even though a Zamboni is a pretty colorful thing to be named after I think my version made Ken Reitz seem even more colorful than he would have seemed if I’d known he was named after a steamroller that smoothed ice. Sometimes things that don’t really mean anything mean more than things that mean something specific. A little magic is lost whenever something gets unequivocally defined. So I imagined The Big Zamboni as a booming friendly guy liked by everyone, the kind of guy who burst into rooms loudly, causing everyone to turn and smile and call his name. Hey, look who it is! The Big Zamboni! From perusing the internet for more info about Reitz, specifically trying and failing to find an article I once read about a famously demon-haunted minor league team in the mid-1980s stocked with former major leaguers trying to climb back up from rock bottom, including Reitz and Steve Howe, I have gotten the idea that Reitz was something like what I’d imagined him to be when I was a kid and knew only his baseball cards and my version of his nickname. I can’t cite any reliable sources on this, so I hope people more knowledgeable on the subject will confirm or deny the sketch I got of Reitz from various message board comments floating in the cyber-ether, but from what I can gather Reitz was a life-of-the-party kind of guy during his time with his primary team, the Cardinals, and the fans loved him and he loved them back, and furthermore loved playing for the Cardinals. For their part, the Cardinals seemed to have trouble making up their mind about Reitz. They traded him away twice, the first time only in effect loaning him to the Giants for a year, the second time packing him off for good along with Leon Durham to snatch Bruce Sutter from the Cubs. He’d been an All-Star a few months before the trade, but Whitey Herzog had decided that he didn’t fit in with plans for the team of speed-burners that would win pennants in 1982, 1985, and 1987. As Herzog put it (quoted by Joe Posnanski), “I used to shave before games. And once Reitz was up at the plate, and he hit the ball, and by the time he got to first base I had to shave again. That’s when I told him he wasn’t going to play.” Herzog, for his part, was known as The White Rat. What nicknames! I’ve never really had a nickname. In boarding school for a little while some people called me Beaker, a hated nickname based on my weakling build and general bug-eyed look of terror. Earlier, at basketball camp, I briefly was known as “I’m Out,” a nickname based on my habit of meek capitulation in the nightly poker games. That’s about it. I’m not the kind of guy who barges into rooms with loud, charismatic jollity. Homeless dudes invariably address me as “Big Guy” before asking me for money. Does that count? Oscar Gamble

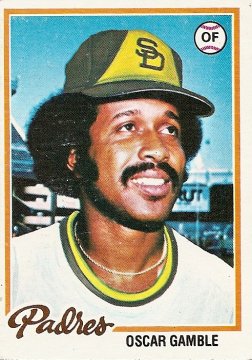

2008-07-22 05:36

I feel I should only approach Oscar Gamble, one of the most memorable figures for us baseball-loving children of the 1970s, in a state of absolute clarity, ready to script transcendent odes to his afro. But since I’ve been at this project of writing about all my childhood baseball cards for quite a while and have yet to write about Oscar Gamble I can only deduce that such states of absolute clarity never exist. No matter how I try to capture Oscar Gamble in words I’m going to blow it, so I might as well get it over with on a nothing morning, a Tuesday after a short vacation, no inspiration or even curiosity in my mind, just a low-level sense of unease that the delayed work week is about to fall on top of me like a collapsing abandoned circus tent. It's a day without possibilities, a day without magic, a day to remain silent, reaching for nothing. But there's Oscar Gamble. There's always Oscar Gamble. In the five heaviest years of my baseball card collecting Oscar Gamble played for six different major league teams. You could never tell for sure where he was at any given moment, so there was always a chance he could appear from anywhere. Maybe even a nothing day has the possibility of his appearance in it. No matter where you are or what you are doing, Oscar Gamble might appear, his swing wicked, jagged, able to wrench pinch-hit homers into the right field seats, his afro billowing below his crushed-down batting helmet as he circles the bases, unfurling to its full magnificence when the batting helmet is removed on the walk from home plate to the dugout, big enough to blot out entire dying galaxies in the sky. His afro! There is hope! Here the caretaker of that famous life-affirming coiffure is shown in two places at once, his doctored home Padre uniform suggesting San Diego while the Brut (by Faberge) sign behind him declares the location of his home stadium as Chicago's Comiskey Park (update: as pointed out by astute readers in the comments below, it is actually Yankee Stadium). If Oscar Gamble can be both here and there then maybe he's everywhere. Even when I'm nowhere. * * * Willie Horton in . . . the All-Time Franchise All Stars

2008-07-18 08:56

So on that note here's Willie Horton, one of the more beloved figures in baseball history. As I see it, Willie does not quite make the cut for the all-time Tigers team, even if a designated hitter spot is added, because the Tigers have no less than four Hall of Fame outfielders ahead of him on the depth chart, plus one other candidate for the DH position, Norm Cash, whose numbers seem to be a bit better than Horton's estimable career record. Cash, by the way, a first baseman who gets sent to the bench by Hank Greenberg, might also have a case for the wild-card position that I have included in these lists as a way of including the one player who can't find a spot in the starting lineup but who needs to be on the team anyway. I'm no expert on how Tigers fans generally feel about Cash, but he played for the team for a long, long time, and if the incident in which he went to bat carrying a table leg late in a game against an unhittable Nolan Ryan is any guide, his personality was surely the kind that would endear him to the fans. But I don't think there's a statue of Norm Cash at the Tigers' current ballpark, and there is one of Willie Horton. I hope that some Tigers fans can chime in about this subject, but it seems from my distant viewpoint that Willie was not only a great player for a long time but was also one of those rare players with a special knack for letting the fans know that the love they are showering down is reciprocal. In a way it's very dumb that we fans put so much emotion into this game, but the truth is, right or wrong, we do. And we want to get the feeling that the players we are cheering for hear us and appreciate it. I think Willie Horton was able to do that.

So he's a member of the All Time Tiger team to me, in the extremely important wild-card spot. As for the other members of the team, I'm going to leave that open for debate in hopes of encouraging smarter fans than me to chime in with their picks. I'll eventually add my own ballot and then tally up the results.

Here are the Tigers batting and pitching leaders. And here's the ballot:

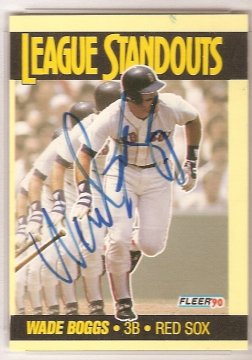

Wade Boggs

2008-07-16 09:37

We carried you I’ve had this propensity to weep for aging male athletes waving to crowds since I was ten years old. That year I got choked up watching the long ovation for John Havlicek during his last game, even though to that point I hadn’t really followed basketball very closely. It didn’t matter, I guess. I was still moved by all the gratitude and sadness of the roaring mob’s goodbye. As the years went by I began to anticipate these moments—last games, retirement ceremonies, the hanging in the rafters of numbers, limping arthritic reunions—the way some other person might anticipate going to a sappy movie to “have a good cry.” And so I was looking forward to last night, when dozens of Hall of Famers would be introduced prior to the All-Star Game. And things were looking good. I was taking it slow, working myself up to a nice happy wet-eyed moment in which I would stand there in my living room alone, clapping and croaking hoarsely “Yeah! Yeah!” In fact, I had already risen from the sofa and was pacing around the room by the time they got to the third basemen, so I think I looked away from the screen before getting a good look at all four Former Greats standing there. All I saw, besides the unmistakable figures of Brooks Robinson, Mike Schmidt, and George Brett, was some bearded guy in a Yankees cap. “Graig Nettles?” I wondered. That didn't seem right, but who else could it be? Turned out it was the guy pictured here. I’m pretty sure he was the only Former Great on the field who chose not to wear the cap that is on his head in his Hall of Fame plaque. Shortly after Boggs’s introduction, Dave Winfield was introduced wearing a Padres cap, but he acknowledged his bond to the Yankees by producing a second cap and holding the two caps up together. Gary Carter did something similar a bit later. This seemed the classy thing to do, the only way to pay tribute to both fan bases that had supported those players for many years. Of course, it would have taken a bit more courage to stand there in Yankee Stadium in a Red Sox cap than in a Padres or Expos cap. Before I describe a few of my immediate reactions to Boggs' failure to display such courage, let me just say that I hate it when the ritualistic sentimental fugues I lapse into during Former Great moments get marred by baser emotions. Spite. Hurt. Anger. Gutless, I said. You’re dead to me, I said. You’re a nauseatingly sycophantic ass-kisser, I said. Nobody thinks you’re cool, I said, tears of rage starting to form. We carried you in our arms, Wade Boggs. It was on Independence Day, as a matter of fact, right there in Yankee Stadium, and a real Yankee, Dave Righetti, struck your ass out to clinch a no-hitter. It was humiliating for this Red Sox fan to see, salt in deep wounds, but I stuck with you. I stuck with you when they started to write that you weren’t a team player. I stuck with you despite your robotic lack of flair, despite your abundantly obvious self-absorption, despite your embarrassing involvement in the Margo Adams mess, despite the hints of cowardice in your “pulling a hamstring” to protect your batting title lead over a real Yankee, Don Mattingly. When you wept in the dugout in 1986, I wept too. And if you’d had the guts to wear the cap that is on your plaque in the Hall of Fame, I'm sure I would have wept again, but happily, joyfully. It took a while, but I had finally become able to accept the existence of the harrowing image of you up on a goddamn horse in pinstripes. You got yours, I could finally say (though it took a World Series win or two for me to be able to say it; I don't deny that I'm a small man). After all, you deserve it. You were a fantastic hitter, a scientist so devoted and pure that you turned science into art. You came along during a rough stretch in my life and the life of my team, my awkward adolescence coinciding with the dreary, lonely Last Days of Yaz, an era that would have been devoid of hope and light without your yearly assault on the summit of the Sunday batting averages. I want to see you in my mind in a Red Sox uniform, peppering doubles off the Monster. But now all I see is you in pinstripes, up on that horse. So Wade Boggs, here’s my response to your appearance last night: Fuck you and that horse you rode off on. Randy Jones

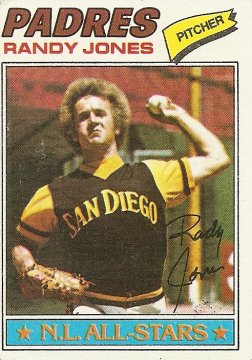

2008-07-15 12:09

This card, featuring the awesome cap-obliterating power of Randy Jones’ Eurfro, celebrates the pinnacle of Jones’ career: his starting assignment in the 1976 All-Star Game. Later that year he was awarded the National League Cy Young award, capping a two-year period in which he was the best pitcher in the league (he’d finished second in the Cy Young voting the year before), but that award was based primarily on his staggering achievements prior to the All-Star break. In other words, the pale junk-tossing star known as Randy Jones never shined brighter than when he took the mound to start the 1976 All-Star Game with more victories, 16, than any pitcher had ever had at the time of the midsummer classic. Aside from the All-Star Game matchup ten years later between dueling phenoms Doc Gooden and Roger Clemens, I don’t think there has been an All-Star Game starting pitching matchup with as much juice to it as the one in 1976. On the one hand, you had Jones, who though perhaps generally forgotten now was at that moment thought to be both an elite pitcher and, more specifically, in stunningly good shape for a run at the already seemingly unreachable plateau of 30 wins for the season. And on the other hand, of course, you had another curly-haired pitcher who just happened to be the most exciting, entertaining, charismatic, and infectiously joyful rookie who ever lived. That was the first All-Star Game I ever watched, and though I was amazed by Randy Jones’ 16-3 midseason record my attention was focused more intensely on his opponent, Mark Fidrych, whom I’d watched for the first time a couple weeks earlier, on Monday Night Baseball, talking to the baseball and mowing down the Yankees as 47,000 Tigers fans laughed and roared. Jones ended up faring better in the All-Star Game than Fidrych, but it didn’t really matter to me. When I was a kid the All-Star Game meant a chance to see the stars from my baseball cards basking in the bright lights, laughing, happy to be there. It was about the moment itself, free of consequences. My brother and I got to stay up past our bedtime to watch the whole game, and it was always the best night of the summer, no matter what happened. Apart from such rare moments, life tends toward disappointment as surely as water tends to run downhill. Randy Jones compiled a 6-11 won-loss record after the All-Star Game, falling well short of 30 wins, and went 43-69 after 1976. Fidrych cooled to 10-7 after the break, narrowly failing to win 20 for the year, and after 1976 went 10-10 during the sporadic appearances that comprised the remainder of his career. The divebombing career arcs of Jones and Fidrych, though by virtue of their brief high peaks more pronounced than most, are still closer to the rule than to the exception. Things fall apart. But when Jones and Fidrych faced off in 1976 they did so in a game that was outside the schedule, outside the standings, outside the inevitable progression toward disappointment. The players wanted to do well, but the result of the game did not matter. It was meaningless. It was a sanctuary. Randy Jones will always be 16-3. Mark Fidrych will always be 21 years old. Lee Mazzilli

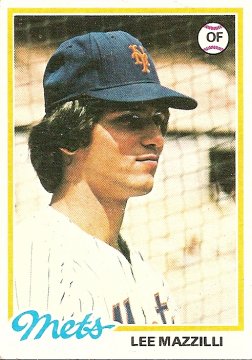

2008-07-14 14:55

Lee Mazzilli was good, not great, at just about everything. He could draw walks, hit for a decent average, smack 15 or so home runs and steal 15 or so bases a year, and cover a lot of ground in the outfield. You could almost say that he was flawless, a characterization that he seemed inclined to emphasize by custom-tailoring his uniforms and maintaining his archetypical feathered haircut with the level of care usually only given to invaluable cultural relics, which in a way is what it was. But in truth he did have one flaw: a relatively weak throwing arm. Ironically, Mazzilli lost out on a chance to win an All-Star Game MVP award because of the powerful throwing arm of another player. In the 1979 All-Star Game, Mazzilli entered as a pinch-hitter in the eighth inning and blasted a game-tying home run, becoming the first player ever to homer in his first All-Star Game at-bat. In the ninth inning he came to bat again and drove in the game-winning run by drawing a bases-loaded walk. Unfortunately, each of his batting feats had immediately followed a half-inning punctuated by right-fielder Dave Parker using the cannon attached to his shoulder to eliminate baserunners. Next to the national debut of Bruce Sutter’s forkball during the 1978 All-Star Game, Dave Parker’s pair of lightning bolts stands as the most vivid All-Star Game memory of my childhood. The voters for the All-Star Game MVP award were similarly amazed, and looked past Mazzilli’s batting heroics to give the award to Parker. Mazzilli never made it to another All-Star game, ensuring that his batting record in the midsummer classic would remain forever flawless. *** (Love versus Hate update: Lee Mazzilli's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Cardboard Books: The Celebrant

2008-07-11 11:07

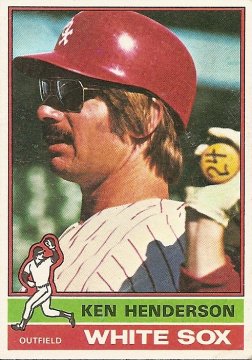

Day in and day out, I follow sports. I’m sure even on the rare days when I’ve been unable to fasten myself to some form of mass media outlet—snowed in and batteryless at the unabomber cabin I lived in for a year, say, or backpacking on the Appalachian Trail—I’ve at least thought about sports. About statistics. About lists. About the actions of uniformed strangers. This makes me a fanatic, to use the extended version of the term most often applied to individuals exhibiting my behavior. Another term often used is spectator. So I’m either mentally unhinged or passive or both. That sounds about right. But is that all there is to it? Eric Rolfe Greenberg offers with the title of his 1983 novel, The Celebrant, a third term to describe those of us whose lives are colored and even defined by our devotion to sports. The book, one of the best baseball novels ever written, suggests we celebrants may have much more at stake in this lifelong passion than we are willing to admit. Ken Henderson

2008-07-10 10:17

The decade in question here at Cardboard Gods may have been the golden age of the switch-hitter. Consider the 1970s all-switch-hitter team: Ted Simmons, C You’ve got one Hall-of-Famer at first, one would-be Hall-of-Famer at third, a catcher with better numbers than many of the catchers in the Hall of Fame, a gold-glove-winning all-star at shortstop, and three excellent, underrated run-producing machines (Singleton, Smith, White). Some would likely argue that Bump Wills is the most obscure member of this team, but to me he always stood out, mainly because of his name, but also because he was the son of a renowned major leaguer, had a notoriously odd baseball card, and was, during my most impressionable years, considered to have the potential to be an up-and-coming star. And he actually wasn’t bad for a few seasons in the late seventies, which happened to be the same time Ken Henderson, my choice as the least known of the all-1970s switch-hitting team, was bouncing from team to team, making little impact anywhere. The card here shows him just beyond the turning point in his career, when he went from a good young player with an admirably well-rounded game to an aging cigarette-ad fugitive gaping out at the action with a bat dangling limply from his fingers. He wears the first of six uniforms he would don over the next six years, never lasting beyond a season anywhere. He was the most itinerant of the members of the 1970s switch-hitting all-stars, and so in a way he's the most fitting representative of that decade of often senseless transience. And since talking about the 1970s without talking about the preceding decade would be like talking about a morning hangover without mentioning the party the night before, it should be mentioned that Ken Henderson in some ways epitomized the 1960s, too. In that earlier epoch he had been brimming with seemingly limitless possibilities, breaking into the major leagues with the Giants in 1965 as a 19-year-old would-be successor to Willie Mays. With that in mind, here’s another list in which Ken Henderson’s name again seems to be the most obscure. Young San Francisco Giants outfielders, 1970s: Bobby Bonds In the 1970s, as it became clear that no new utopias were going to spring to life out of sheer visionary ecstasy, and for that matter that no one would ever replace Willie Mays, everyone seemed to suddenly start growing older in bursts. Skin that had long been unblemished suddenly became slacker, creased, faintly greasy. Mustaches were grown, Marlboros lit, aviator shades donned. Throughout the land it became increasingly difficult to tell what people were thinking, in part because of the tinted eyewear, in part because the thinking itself, once so sure of itself, had unraveled into the uncertainty of a switch-hitter who has lost the ability to hit from either side of the plate. Bill Travers

2008-07-09 06:38

Since I have always lived more in my mind than in the geographical location where I receive my mail, and since that mind has more often than not focused itself on baseball, it’s accurate to say I grew up not in any particular state or county but in the American League East. The Brewers were there, for the first few years a blurry, negligible presence, like a quiet, nondescript kid in the back of the class, the kind who never seemed to change from year to year (not that anyone was ever really looking, not even the teacher). Then gradually as the ’70s waned that kid hit a testosterone-heavy growth spurt and hair exploded from his face and he got suspended for bringing a switchblade to school and suspended again for knocking his vocational arts teacher unconscious and in general made you feel uneasy when you passed him in the high school parking lot as he leaned on his dented Camaro with his eyes hidden behind mirror shades and his hands on the Wrangler-bejeaned ass of his raspy-voiced world-weary girlfriend. Ah, the Brewers of my puberty years. I didn’t realize I’d miss them when they followed that brief loud prime by receding into anonymity again, hair disappearing, muscles liquefying, bravado reduced to the occasional impotent beer-drunk rant against the many encroaching borders of life. I imagine as they first moved into this anticlimactic phase of their lives they resembled Bill Travers, still young, cleanshaven in accordance to employee rules, the only change from one year to the next the slight shift of facial expression from confused and questioning to confused and blurrily, sadly resigned. Who even knows when they moved out of the American League East? One day you drove past their trailer where they’d spent the last several useless years, and the weeds spouting up through the engine of the dented Camaro up on blocks seemed even more overgrown than usual, no sign of the Brewers or the no longer scrawny but still world-weary woman or the couple's several nondescript towheaded quietly crying kids. I still live in the American League East for the most part, i.e., in my mind, but I get my mail in a region affiliated most heavily with the National League Central. Turns out this is where the Brewers moved, like a factory worker who decided when the factory relocated that instead of taking severance pay he’d move the whole wreck of his life to another state entirely and take his chances there. Nothing really changed. Year after year the Brewers punched the clock. If a baseball card were produced to personify each of these years, the series of cards would again resemble the 1975 and 1976 cards of Bill Travers, as if the meek unchanging anonymity of childhood was the inescapable fate of their life. Last night I listened to the end of the Milwaukee Brewers game on the radio. The crowd was roaring. Their newest acquisition, a towering, charismatic beefster, got the win, one of their two great young sluggers, an obese vegetarian, drove in a run, and their other great young slugger, The Hebrew Hammer, blasted a three-run homer. In other words, for the first time in many years, I looked straight at the Brewers, and it turns out the Brewers seem to have a glimmer in their eye like they might just throw a bowling ball through a plate glass window or put a guy in a headlock in the parking lot of a Molly Hatchet concert or find that long-missing part for their dented Camaro. In other words, lock up your daughters. Here come the long lost Brewers. Bob Bailey

2008-07-07 12:49

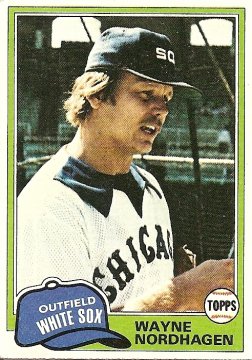

Bob Bailey never commanded much of my attention when I was a kid. To be honest, I don’t even remember him coming to bat for the Red Sox as a pinch-hitter during the 1978 one-game playoff against the Yankees, which in general was the most memorable game of my childhood. In that awkward, wounded, sprawling decade, Bob Bailey quietly blended into the background. Once he disappeared entirely from view I began to confuse him with Bob Bailor, who flickered to marginal life in the majors just as Bob Bailey was fading. I understand now that utility infielder Bailor was nothing like underrated masher Bailey, who for several years held many of the Montreal Expos all-time slugging records. But as the above duo of cards reflects, even the Expos were capable of underestimating Bob Bailey, shipping him to the Reds for Clay Kirby, who in the season prior to the trade, despite pitching in front of four Gold Glove winners, posted a 4.72 ERA, over a run higher than the league average. Of course, the above duo of cards also suggests that Bailey let nothing, not even a complete change of scenery, affect his approach to the game. Let the rest of the world stumble and panic. Let the rest of the world try out new styles to cope with profound transience, with the widespread crumbling of societal norms. Let the rest of the world grow long hair and beards and mustaches and attend EST meetings and quit their jobs to sell homemade hammocks and get divorced and meditate and learn the Hustle. Bob Bailey is going to keep being Bob Bailey. He is going to stand there, implacable, and wait for his pitch. Fittingly, Bailey did his usual thing for the Reds (.298 batting average/.376 on-base percentage/.508 slugging average), albeit in limited duty (227 at-bats), but did not play in the postseason. The Reds shuttled him to the Red Sox near the end of the next season, and the following year he was sent to the plate to bat for Jack Brohamer in the seventh inning of the one-game playoff game against the Yankees. His last career at-bat, as it turned out. He was the potential tying run. Goose Gossage was on the mound. It was a big moment, but he surely stood in the batter's box the same as he always had. Waiting for his pitch. Waiting for his moment. Three pitches later he was walking back to the dugout. I have a card for him on the Red Sox that year, and he seems in that card too old to still be waiting for his pitch. But I'm older now than he was then and I'm still waiting for my pitch. Waiting for my moment. I hate Goose Gossage. Wayne Nordhagen

2008-07-04 08:28

There’s supposed to be a parade today in Randolph, Vermont. Thirty years ago I marched in a version of it with my teammates, all of us in our green caps and baggy green and gray baseball uniforms. There were floats and brass bands and gleaming fancy antique cars whose horns went aroooga. There were many people lining the streets, practically everyone in the town. But it’s a small town; you can hear individual voices saying "Yay!" The guy up on stilts, dressed as Uncle Sam, will be someone you know, maybe even an actual uncle. *** Yesterday in Randolph hundreds gathered to grieve for Brooke Bennett. Family members, friends, and clergy members took turns speaking to the crowd. One of the speakers was the man who replaced my first little league coach when my first little league coach’s son got too old for little league. I keep running into my past in this story. Yesterday, articles about Brooke Bennett included quotes from her seventh grade math teacher, who was my seventh grade math teacher in 1979. Today I read what my second little league coach, Reverend Ron Rilling, pastor at Green Mountain Chapel, said to the crowd in Randolph yesterday. "We gather together as a community to affirm that love is more powerful that hate," he said, "that faith and hope are better chosen than fear and despair." *** Yesterday an online message board linked to this site, to my story about the son of my first little league coach. The message board thread was entitled "Another angle on the Uncle Pervert story." Uncle Pervert. I guess this is one reason why there are national news vans clogging up the narrow streets and dirt roads of Randolph. The apparent author of the hideous act is a relation. An uncle. We like to believe this is unthinkable. My wife, a social worker, works with teenagers whose extremely difficult pasts often include being victimized by sexual assault. The majority of these crimes are committed by people within, not outside, the boundaries of the family. *** "I remember when I was 13 years old, I went to Spring Training with my uncle Wayne Nordhagen, who played for the Cubs. Just being on the field and being around the guys in the locker room, it gives you so much when you’re a kid." – Kevin Millar Kevin Millar’s uncle shares a birthday with Uncle Sam. He’s sixty today. That’s a little younger than the youngest of my five uncles. I thank Wayne Nordhagen for being a good uncle to Kevin Millar, because Millar’s fond words about his uncle have suggested to me a way to try to follow the advice offered yesterday in Randolph by my second little league coach. Love is more powerful. Like Kevin Millar, I grew up with uncles who gave me a lot. My uncles took me to baseball games. My uncles made me laugh. My uncles taught me useless, marvelous skills, such as how to pass a finger through the burning flame of a candle and how to build the perfect plate of bagel and lox and how to body-surf in the Atlantic Ocean. My uncles provided me places to stay when I seemed to have overstayed my welcome everywhere else. My uncles provided and provide to me a host of examples of how to be a good person. My uncles have always helped make me feel that I was loved, that I had a place in this world, a permanent seat at the table. A safe haven. I know today is supposed to be about Uncle Sam and detonating small explosives, and that there’s another holiday set aside for giving thanks. But this Fourth of July I’m saying a prayer of gratitude and love to my own uncles and all the good uncles of the world. The Coach's Son

2008-07-03 05:39

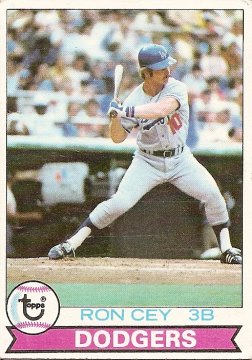

The happiest I've ever been was when I was playing little league baseball. I'm not saying I was always happy during those years when I was nine to twelve years old, or that I haven't had my share of good moments since, just that when I was playing, when I had on that baggy gray and green uniform, that green cap with the white felt M, when I was pounding my glove out in centerfield and waiting for the pitcher to pitch and singing to him in that cricketing chant that flowed in toward the mound from every corner of the field, nabada nabada nabada, when I was waiting for the game to kick in, waiting to make a catch and make a throw, waiting to run in a hop-skip-sprint back to the dugout to talk and laugh and take my turn at bat, waiting to feel that sweet numbness of connecting with a pitch, that was it, the most I could ever ask for from life, the summer coming on and baseball to be played. That was it. I can feel it even now at the top of my throat, like a swallowed-back cheer, like the sun about to burst free from the gray. I still remember the car my first little league coach drove. It was a green sedan with a white roof. I don't remember what he did for a job but he drove all over town all the time, sometimes even passing by my house, which was pretty far away from everything. More than once my brother and I were playing baseball in the side yard when he drove by. He'd honk and wave. My brother and I waved back. I felt proud, like I mattered. At the end of each of my first two seasons we all gathered at my coach's house and helped him take down the rubber tubing and metal buckets that he'd attached to all the maple trees on his land. It was fun walking through the woods with my teammates, working together, calling out to one another through the trees. Afterward, by his sugar house, the coach fed us sandwiches and told us funny stories. I don't remember anything about the stories except that he punctuated all dialogue by saying either "he says" or "I says." He stopped coaching our team after my second year because his son was done with little league. He'd batted his son leadoff even though he wasn't a very good hitter and used his son often as a pitcher even though his pitches were both wild and slow. He was not really the prototypical coach's son in that the prototypical coach's son is a kid without the talent to go with his overdeveloped technique, the coach pounding into the slow, undersized kid the textbook way to do everything. But our coach's son compounded his lack of talent with clueless, histrionic stabs at technique, like Carmine Ronzoni in the early parts of The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training. Amazingly, he never seemed to doubt his clearly shoddy abilities. A few years after little league, my stepfather, Tom, went to get an oil change at the gas station up by the interstate. The coach's son was the only one on duty, and he assured Tom that he knew how to realign tires. Tom was skeptical, but the coach's son kept insisting that he had nothing to worry about. A little later, Tom drove away in a car that listed toward ditches. This was how the coach's son played baseball. But oddly enough I don't remember any hard feelings on my team about this garishly obvious case of nepotism. Maybe there were some grumblings, but for the most we weren't yet capable of bitterness, jealousy, spite. We were just glad to be playing baseball. And the coach was a nice guy to all of us, and though his son was sometimes kind of a fool he was harmless. Seemed harmless. Tomorrow is the anniversary of my peak as a little leaguer, when as a 12-year-old I played in my town's annual 4th of July all-star game against a team of players from nearby towns. I can't imagine what that game is going to be like this year. Perhaps they'll cancel it. The all-stars are the same age as a girl from the town named Brooke Bennett, whose body was found yesterday after she was reported missing a week ago. The girl was last seen exiting a convenience store with her uncle, a registered sex offender. This is the man who is pictured at the top of this page. He was already in custody for sexual assault at the time the body was found. According to the testimony of a 14-year-old girl who claims to have been getting sexually assaulted by this man since she was nine, the man seems to have been in the habit of telling girls his assaults were part of an initiation into a sex ring. He threatened to cut their throats if they resisted. Many years ago this man batted leadoff and pitched for a team coached by his father. When he was on the mound I stood in centerfield. Nabada nabada nabada. When he threw a pitch out of the strike zone our mantra changed. Throwstraahks throwstraahks throwstraahks. When he did throw a strike a sound burst from my throat like laughter, sunshine, happiness. His name. Ron Cey in . . . The Franchise All-Time All-Stars

2008-07-01 10:49

Be warned: the following further installment of The All-Time Franchise All-Stars is both derivative and ill-informed, probably more so than the earlier installments, which were focused on teams, the Expos and Mets, that I know a little better than the team profiled here. Though I have, in an effort to retain some semblance of originality, lately avoided looking at Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Lineups, which is a multi-acre amusement park compared to the tangled yo-yo of this ongoing feature, it’s a good bet that whatever I get right in my picks for the all-time teams of any franchise owes to earlier readings of that book. But who knows, maybe all we can ever really claim as our own is what we get wrong. So on that capitulatory note, here’s how I see the Dodgers all-time team. (In parentheses after each player mentioned is their positional ranking, if available, from The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract.) If it seems to you at any time that I’m in way over my head, please feel free to throw me a Dodger blue lifesaver. |