|

Monthly archives: April 2007

Ron LeFlore

2007-04-30 09:40

Happy Conclusion This morning, while trying and failing to find an eloquent way to finally wrap up "Happy," which is surely the least focused, most digressive multipart Cardboard Gods series yet, I came upon an amusing site called Baseball Heckle Depot, which generously provides material for broadening one’s repertoire for yelling things at baseball guys, such as "Do you want my autograph?" and "You’ve got less hits than an Amish website!" The "True Stories" link brings you to a page that includes, among many other anecdotes featuring the beered-up and seated hurling invective down upon the standing, the following fan’s-eye view of the All-Star pictured in this 1977 card: Ron LeFlore was a member of the Detroit Tigers back in the 70’s, and he was discovered by the late Billy Martin while in prison playing semi-pro ball. LeFlore could steal bases with the best of them, and had some pop in his bat, but wasn’t much of a fielder, which was no small source of frustration for Tigers fans. When a fairly routine grounder rolled through Ronnie’s legs in a tight game one night, the guy behind me yelled "Hey LeFlore, why don’t you pretend you’re still in the prison leauges [sic], and bend over!!" I wonder what my conception of prison was before I read Ron LeFlore’s 1978 autobiography. When I was a kid, I developed my reading skills by reading very little else but baseball books, so whatever knowledge I had of the world beyond baseball and my rural Vermont town came to me through the comic book exploits of Spiderman and The Fantastic Four and television shows such as Happy Days, Lost in Space, Batman, Kung Fu, The Waltons, Wonder Woman, and Welcome Back, Kotter. With that in mind I probably viewed prison in my pre-LeFlore era as a barred room where exotically colorful villains or stoic, wrongfully accused heroes would occasionally be placed until they could escape to wreak more havoc or exonerate themselves, respectively. This conception, along with the fact that the idea of prison did not exist in the great majority of the shows I watched (unless I missed an early Happy Days episode in which Richie’s older brother was sent away to the Big House for life for something unspeakably heinous, which would have explained Stretch’s abrupt, final, never-mentioned absence from the show after Season One), must have made prison vague and safely distant to me. I had plenty of things to worry about as a kid, as all kids do, but prison was not one of them. At least until I read Ron LeFlore’s autobiography, that is. I really don’t remember much about the book, but I certainly do recall the author describing the inmate practice that served as the punchline of the above heckling anecdote (and of the great majority of all prison-based humor). If I recall correctly, LeFlore himself managed to avoid the culture of ass-rape, but even so his description was enough to alter my idea of what it might be like if I was ever tossed in prison. Worse, LeFlore’s tale came in the context of baseball, which made up more of my world than anything else you could name. It was a baseball story, and since my life was built on baseball stories, it was a story about my life. Hence, prison—and not the kind of prison where Burgess Meredith’s Penguin might waddle around squawking for a few minutes before knocking out the guard with sleeping gas from his umbrella and escaping, but the kind of prison where a baseball player saw ass-rapers running across the yard with shit on their dicks—became a part of my life, or at least a new thing to fear. So far, knock wood, I’ve managed to avoid prison. I’ve even avoided prison’s more temporary, booze-scented cousin, jail. I have been briefly handcuffed twice, but in the manner of practically every episode of Kung Fu, each of the apprehensions by authorities was wrongful (I only wish I could have had the presence of mind in each case to utter a couple pause-filled, soft-voiced Kwai Chang Caine-isms, something like "The Way . . . forgives . . . the sad cruelties . . . of man" or "The gentle reed . . . bends . . . in even the very strongest . . . wind."). In one instance, after a Red Kross show in Hoboken, two of my friends had gone through a New Jersey Path Train turnstile together, and cops staking out the station who thought I was one of the fare-beaters also thought I was resisting arrest when I continued to walk down the train platform after they had yelled at me to stop. A few years earlier, while living in a house in the woods with four other students, I’d been yanked out of my bed late one night and cuffed when a very odd girl who lived at the house, and who believed she was alone in the house that night, called 911 to report what she thought was an intruder. Other than that, I guess my experience that most closely resembled the kind of thing that might lead to incarceration was when I got busted at boarding school for participating in one of the joyous bong sessions described earlier in this four-part exploration. This bust led to my expulsion and to the expulsion of the one other person in the room who, like me, had committed an earlier suspension-worthy transgression at the school. This other person was my friend Happy Al Raymond. I only saw Happy Al once after the day we were both sent packing. It was the following year, when some of us returned to the school during the homecoming weekend to get plastered together in a room at an Econo Lodge near the school. Al had thickened just a little around the middle by then, the slight alcogut the most easily visible element of his embrace of a new persona, that of the superficially and generically merry frat boy. He had a beer mug in his hand the whole weekend, and his standard reply to everything was a polished bark of laughter and little else. And that was it. No more Happy Al. Nobody saw him again, nobody heard from him. I embarked on a largely aimless existence built around a vague desire to live a life that included writing, naps, and respite from loneliness. It turns out that while I was groping in my half-assed way toward my lazily conceived idea of happiness, Al was becoming an extremely successful Republican Party campaign operative. I don’t know if this made him happy, but I have always assumed that highly successful people are driven to their success in part by the happiness they find in doing their job. By 2002, he had apparently become the go-to guy when a certain kind of campaign business needed to be done. His most celebrated or notorious exploit to that point (depending on your political leanings) had been when he’d engineered the mass blanketing of New Jersey households with calls right near kickoff of the Super Bowl. The calls, which were meant by virtue of their timing to be an annoyance to everyone who received them, were negative attacks on one rival candidate sent (it was ingeniously and fraudulently implied) by another rival candidate, smearing both. With this and other campaign triumphs on his resume, Al’s political campaign consulting firm was contacted in 2002 with a job that other similar firms had turned down. They’d all wanted no part of it. A high-ranking Republican Party member, James Tobin, contacted Al, as related by the back and forth between Al and a questioner in court transcripts from Tobin’s trial: Q: What does he say? (Next: The riveting, all-encompassing, elegaic epilogue!) Steve Braun and Steve Brye

2007-04-24 08:35

Happy Chapter 3 If you Google the word "happy," you get 484,000 results. At the very top of the first page of results is a listing for "Happy Harry’s," the name a national drug store chain uses to distinguish—and, judging from the drawing of the kindly, smiling man who appears in the Happy Harry’s logo, to humanize—that most lucrative section of their countless identical franchise branches. The slow-moving line at a chain store pharmacy has never struck me as a happy place, the day leaking away as you wait interminably amid moaning soft rock behind the depressed, the aching, the phlegm-ridden, the venereally diseased, but according to Google it’s the top place for happy in all the cyber-accessible world. Also topping the Google search page for the word happy is a Japanese pop band, a Wikipedia entry for "happiness," the movie Happy Feet, a couple different incomprehensible tech-related pursuits, the "Happy Tree Friends" ("cute, cuddly animals whose daily adventures always end up going horribly wrong"), something called HappyNews.com ("All the news that’s fun to print"), which is running as its top story today a piece about good reviews for a new book about the genocidal Khmer Rouge (good times!), a USA Today article that passes on a psychological study revealing what makes people happy, and two different websites that claim to have the answer to the question of how to be happy. If you Google "Steve Braun," you get 59,900 results, the majority having nothing to do with the man apparently poking at a dead alligator carcass with his bat in the baseball card on the above left. But his page on baseball-reference.com does come up, and there you can view the 15-year veteran’s admirable .371 career on-base percentage. Two sites down on the Google search page is a link to Steve Braun Baseball, an organization determined to pass on the ballpark wisdom of Steve Braun. If you Google "Steve Brye," you get 3,730 results. Unlike the Steve Braun search, which quickly yields up words from the mouth of Steve Braun, or at least from the mouth of the baseball guru entity known collectively as Steve Braun Baseball ("Our mission is to ensure every player builds confidence and comprehends what it takes to reach their full potential"), the Steve Brye search requires the user to scroll several pages in before coming to an entry that gives Steve Brye a voice. It’s an article about a game between the Royals and Twins on the last day of the 1976 season that decided an usually tight race for the batting title between four of the game’s participants: Rod Carew, Lyman Bostock, George Brett, and Hal McRae. Brett ended up winning the race for highest batting average, but only after Steve Brye badly misjudged a seemingly catchable fly off the bat of the eventual champion’s bat. The goof-up, which was officially scored as an inside-the-park home run and which allowed Brett to edge into the lead by a hundredth of a percentage point, did not sit well with Brett’s teammate, McRae, who accused the Twins of conspiring, at manager Gene Mauch’s command, to hand the batting title to the white man, Brett, instead of letting the black man, McRae, win it fair and square, which from this remove at least seems an odd accusation, given that the two Twins contenders for the title, Carew and Bostock, were black. According to the article, Steve Brye was equally mystified, and even saddened, by McRae’s claim:

It should be pointed out that funny business involving late-season batting races was not unheard of in baseball history, most notably in the 1910 race between Nap Lajoie and Ty Cobb (to read about the "chicanery" in that race scroll down to page 6 of the May ’01 issue of The Inside Game). And McRae was joined by black teammates Amos Otis and Dave Nelson in casting aspersions on Steve Brye’s supposed misplay (meanwhile, two of Brye’s black teammates, Rod Carew and Larry Hisle, were quick to dismiss the possibility of an anti-McRae conspiracy). I guess the only thing that could be said without any equivocation about the controversy was that nobody really came away from it (here's that word again) happy. If you Google the name of the least happy of that game’s participants, "Hal McRae," you get 45,700 results. The second listing (after a Wikipedia entry) is entitled "Coach McRae Goes Nuts." Before I post the link to that site, and to the vivid portrait of enraged unhappiness offered by the YouTube clip on the site, however, I want to offer, free of charge, my personal four-point answer to the question of How to Be Happy: 1. Digress. Whenever life calls you to go from point A to point B, go to point C or point J or even Point Break, the ridiculous extreme sports action movie starring meatheads Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze, the latter's early films including The Outsiders, which was a favorite of a girl I daydreamed about incessantly in the pubescent years directly following my baseball card collecting years, which had brought the shabby but beautiful symmetry of these Steve Brye and Steve Braun cards into my life. Where is that girl now? Let me see. Hold on. From Google: "Your search – 'maureen gaidys' – did not match any documents." Ah, the sweet sad lost ungoogleable lands of youth! 2. Procrastinate. This is really just an extension of point 1, above. And I actually had what I thought was a better idea for point 2, but first I really should go clip my nose hair. That will bring me sort of close to the kitchen, and there’s some chocolate in there that isn’t going to eat itself. It’s early yet. Is it too early in the day to take a nap? I read that naps are good for your heart. Maybe just a quick one then... 3. Oh, god. What time is it? Christ, coming out of naps is like trying to crawl out from under a giant wet carpet. Give me a few minutes here . . . OK, on to point 3: Don’t finish what you start. Who has the energy to anyway? And even if you did have the energy, why would you want to finish something? Who wants things to end? You? Then how happy are you going to be when the sun goes supernova eventually? Hey, it’s just finishing what it starts, happy completely-obliterated-in-a-cosmic-explosion guy. Enjoy! 4. Yeah, uh, about point 4: See number 3, above. Now where was I? Who cares, really, at this point. Before I started weaving all over the road today I had it in mind that I was going to talk about the most aesthetically pleasing platoon in baseball history, that of Steve Brye and Steve Braun, and how the platoon and the mirroring 1975 cards which so aptly represent it make me wonder if being part of a platoon is the key to happiness in this annihilation-bound solar system. You do your part, someone else does their part, and together you make up a whole. When I was writing in very loose relation to Hal McRae a couple days ago about the happy feeling of getting high at boarding school, I neglected to get across the huge part the communal feeling played into creating the happiness. Just prior to those couple years at boarding school, I’d been an isolated, lonely kid, filling up the hours playing solitaire Stratomatic and dreaming about the ever unreachable, ungooglable Maureen Gaidys. Then at boarding school I was suddenly part of a group, part of a team with the goal of communal inebriation and flight and deep wild laughter. Suddenly there was a Steve Braun to my Steve Brye, a Steve Brye to my Steve Braun. Anyway, now, finally, three chapters into this longwinded saga, I’m finally going to get around to mentioning the titular subject: a boarding school friend of mine who I haven’t seen in over 20 years, Al Raymond. The title of this piece is based on his nickname: Happy Al. A Google search for "Happy Al" yields 27,100 results. A Google search for "Al Raymond" yields 12,500 results. A Google search for "Alan Raymond" yields 21,800 results. None of the results for any of these searches seems to reference the friend who helped bring to my time at boarding school some of the highest, happiest, laughingest hours of my life. But the top result of a Google search for "Allen Raymond" is a Washington Post article entitled "Former GOP Consultant Sentenced to Prison." The second result is a political watchdog webpage entitled "Who Is Allen Raymond?" I’ll report what I found out about who Allen Raymond is in the next and final chapter of Happy, but for now I just want to tell you who Happy Al is. Or was. Specifically I wanted to pass on the origin of his nickname, which stemmed from an event that occurred the year before I arrived at the school. I’m going to let another friend from those days tell the story as he told me in a recent email in response to the theory that he was called Happy Al because of the merry slit-eyed facial expression that he displayed when stoned:

At this point I want to offer as a visual aid the aforementioned and promised Hal McRae video. For a look at what one of my friend Al’s tantrums looked and sounded like, approximately, please click on this link of Hal McRae going berserk. OK, have you put that in your [expletive] pipe and smoked it? You really owe it to yourself to do so, but if not, just imagine somebody ranting and screaming and throwing things around. Now with that in mind, back to the eyewitness account:

(to be continued) Hal McRae

2007-04-22 06:55

Chapter 2 After the first time I got busted at boarding school, for stumbling around plastered on rum at a school dance, I was put on probation and forced to attend a weekend encounter group with other students who had run afoul of the section of the campus code of conduct pertaining to drugs and alcohol. The group was run by the campus counselor, whose purpose, I suppose, was to try to get us to understand why we were engaging in behavior that had led us to the group. We did some "drug-free" stress reducing exercises such as lying on the rug of the classroom with the lights out and tensing and untensing various parts of our bodies while imagining ourselves lying by some quiet generic placid lake with strong zoning against jet-skis and whatnot. When that was over we got up and sat in the metal and formica chairdesks of the classroom, which happened to be the same classroom in which I was failing American History, and the counselor tried to get us to talk about our feelings especially vis a vis getting drunk or high. I participated far less than any other student, having none of the polished insights that the other students were able to flawlessly unleash like country-club-taught tennis court backhands. In that way it just seemed an extension of all other public life at that school: the other students there all seemed more sophisticated, mature, and intellectually advanced than me. The one insight I still recall from that weekend encounter group was from this bleary-eyed red-headed kid who saw part of the allure of smoking bong hits as deriving from its ritualized aspects. Smoking pot at boarding school certainly was ritualized, much more so than in any other pot-smoking context I’ve been in since: You get the lights in the room just right. You put on the right record. You roll up a towel and put it in the crack between the door and the floor. You remove the bong from its hiding place in the closet. You roll up another towel to use as your "hit towel." You pack a hit in the bowl of the bong. You remove from the top of the bong the odor-trapping device known in the typical homoerotic slang of the school as the "dick" (some "dicks" were fashioned out of big wads of masking tape; others were simply objects that happened to be the perfect size to stop up the head of the bong, such as the upside down—and depantsed—Mr. T doll we used in our bong). You light the bowl. You take the hit. You hold it. (Here’s where things usually start to go wrong. Guys start coughing or guys bust out laughing. The room fills with incriminating smoke amid accusations and, because everyone's getting stoned, hilarity. This is known as "blowing" the hit.) If you are able to hold the hit without "blowing" it, you exhale into the hit towel, leaving a brown marijuana kiss on the fabric. I see all this now but at the time of the drug-free weekend I had never once thought of it that way. The red-headed kid used as an illustrative metaphor for his theory the ritual of eating a piece of Bazooka Joe. A big part of the fun of eating a piece of Bazooka Joe, he explained, is the ritualistic unwrapping of the gum and the reading of the comic and the fortune. In that sense I had been exhibiting the behavior that would lead me to the encounter group for years and years, ever since participating chronically in the ritual of opening baseball cards: You buy the cards and before opening the pack you carry the pack home, feeling the bump of gum inside and the stack of brand new cards, that moment of wide open possibilities in some ways the best moment of all. Once you are in the perfect place for unveiling the new pack, you slide your forefinger under the lightly glued flaps, opening them, releasing the gum scent into the room. I always blurred my vision at this point, not wanting to know the identity of the first card visible below the flap. That card was always face down, and I had it in my head that the first card I learn the identity of should be face-up. As I flipped the stack of cards the plastic wrapper fell away and I slipped the stick of hard gum in my mouth and broke it up and chewed, releasing the sugar just as I began to look to see which Cardboard Gods were a new glowing part of my own little solitary world. But even when the red-headed kid had presented his theory I had partially disagreed with him for what I intuitively felt was missing from the theory. I didn't actually voice any disagreement, and wasn't even able to put the disagreement into words in my own mind. I think, at the time, my first thought was: "That’s it? That’s all getting high is? Chewing Bazooka Joe?" Basically, the pale red-headed kid had offered a perceptive but completely joyless explanation. To me, getting drunk and getting high were huge. I mean they were these experiences that dwarfed the everyday happenings that made me feel small and useless. They were openings into whole other worlds. His theory left out that feeling, and more than that left out the fact that when we got high we laughed so hard tears rolled down our cheeks. If he’d been talking about the ritual of opening packs of baseball cards, he would have described the process as I did above, and he would have stopped there, leaving out a description of the revelations and visitations the ritual led to. He would have left out, for example, the feeling of finding this beamingly happy 1976 Hal McRae card in a brand new pack. This is why I bought cards. This is why I smoked pot and drank alcohol with my friends at boarding school. It made me happy. It threw open the shutters. It let in the sunlight. Bob Welch

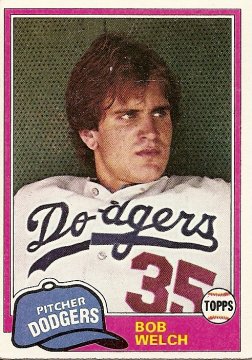

2007-04-19 03:59

Happy Chapter 1 (1981) Bob Welch doesn’t look happy. It’s 1981. I was 13 that year, and though I was withdrawing abruptly from the collecting of baseball cards—this card one of just a few I bought that year—I’m sure I still viewed the life of the major leaguer as the happiest possible existence. And who among major leaguers could be happier than a 24-year-old former number 1 draft pick who threw blazing fastballs, who had just cracked the vaunted Dodger starting rotation with a promising 14-9 record, and who had just a short while before that authored one of baseball’s greatest moments? Yes, just a short while before this unhappy picture, Welch had been called on to preserve a 1-run lead in the 9th inning of game 2 of the 1978 World Series. As he warmed up by firing a few of his electric fastballs the announcers remarked on the 21-year-old rookie's lack of experience (just 14 games in the majors thus far) and on his reportedly boundless potential. There was one out, two men on, and two of the most dangerous and fearless hitters in the game due up. Thurman Munson stepped in first and flied out. Then Reggie Jackson strode to the plate. When the confrontation was over, Dodger outfielder Bill North would tell Time Magazine that it was "the best show I’ve ever seen. The game’s best fastball hitter up against a kid who throws as hard as anybody in baseball." The at-bat would take seven minutes to unfold. The count would go to 3 and 2. "It was like the 15th round of a heavyweight championship fight and you knew both guys had won seven rounds," North continued. "Bob just aired it out and said, ‘Hey Reggie, here it comes. If you can handle it, you deserve it.’ It had to end in a home run or a strikeout." With his home crowd roaring Bob Welch reared back one final time and fired. When Reggie swung ferociously and missed, Bob Welch burst into myth. Welch began to come back to earth almost immediately, allowing a deciding Yankee rally (including a single by Reggie) in the 10th inning of the very next game and giving up two runs (including a home run by Reggie) in another loss in the Yankees’ series-clinching win in game 6. But like the 1975 Carlton Fisk home run, Welch’s spot in the limelight seems to have shucked off the more prosaic details of his team’s eventual defeat as the years have gone by to take its place among the more treasured moments of baseball lore. I’m glad about this as a baseball fan who likes to sift through the jewels of the collective memory of the game. I’m also glad about this as someone bent on using baseball as a metaphor for my own life, for if eventual defeat obliterated the good moments my past would be a bucket full of ashes. You can’t take shelter in those good moments. I doubt that Bob Welch ever tried to do so with his legendary strikeout of Reggie, but maybe he wasn’t immune to the very human urge to compare the swampy complexities of existence to the gravity-free clarity of glowing myth. I don’t really know what happiness is, but unhappiness could probably be defined as the painful, disappointing gap between life as it actually unfolds and life as it appears in quick-dissolving moments of exultation, victory, bliss. Anyway, Bob Welch doesn’t look happy in this 1981 card. He looks like I probably did fairly often that same year, when I was 13. Baseball was shrinking from a happy, all-consuming passion to just one more thing that I wasn’t really that good at. My brother was heading off to boarding school. I drifted away from the close friends I’d made at my deskless hippie elementary school classroom and replaced them with empty space and an ever more complex fantasy life and a few superficial acquaintances. The next couple years were pretty rough for Bob Welch and me, but for different reasons: He drank too much, and I didn’t yet drink at all. But things change. Welch got himself sober and won a Cy Young award, a World Series champion ring, and retired with 210 lifetime wins. As for me, I went off to boarding school at 15 and made some friends and started drinking booze and smoking pot. This was right around the time when Nancy Reagan was blanketing the airwaves with her message to "Just say no" to drugs, but when we got high we laughed until tears were rolling down our cheeks. Why in the world would I say no to that? (to be continued) Johnny Oates

2007-04-17 08:45

Here is Johnny Oates, member of the Virginia Tech Hall of Fame. He was selected by the Baltimore Orioles in the first round of the 1967 draft while still enrolled at Virginia Tech but only signed with the Orioles on the condition that he could stay in school long enough to graduate. He was born and raised in North Carolina, and was at the time of this 1978 card spending the majority of his spring, summer, and fall in Los Angeles, but, according to the back of this card, his home was in Virginia. I’m going to go out on a limb and surmise that he enjoyed his time as a baseball superstar at Virginia Tech. He certainly never attained that level of stardom in the major leagues, though he was a decent enough left-handed hitter to find employment as a backup or platoon catcher on 5 different teams in an 11-year major league career, 3 of those seasons ending with his team playing in the World Series. He found greater success as a manager, leading the Texas Rangers to 3 division championships in the 1990s. His number has been retired by Virginia Tech and by the Rangers. He died of brain cancer on Christmas Eve of 2004. I don't know what you can say about brain cancer taking away a man who should have had many more years on this earth. And I certainly have no fucking idea whatsoever what you can say about the mass murder of 32 students at Johnny Oates’ alma mater yesterday. A few years ago I watched from the window of my Brooklyn apartment as the two World Trade Center buildings fell. Not long after there was nothing but the huge black cloud where the buildings had been, my roommate Pete went to see his girlfriend a few blocks south, and I walked several miles to my girlfriend’s house in Queens. I walked against the grain of the thousands and thousands of people who had evacuated Manhattan by foot across the Queensboro Bridge and were then moving from Queens toward their homes in Brooklyn. When I think about words in terms of horrific events, I think of the moment when I was crossing the Pulaski Bridge into Queens against this sea of stunned people in their ash-covered work clothes. A United States fighter plane ripped across the sky above us. I stopped to watch the jet pass, as did a man walking the other way. When it had quickly disappeared from sight I lowered my gaze and my eyes met those of the Brooklyn-bound observer. "Too late," the man said. That’s what I think of any and all words in the aftermath of unspeakable events. Too late. You can look for someone to blame, some way that some or all of the bloodshed could have been avoided. You can psychoanalyze the murderer. You can send in troops or fighter jets or extra security to check everyone for handguns and grenades. You can even make speeches and talk about God. Too late. All of it. Too fucking late. I see Seals . . . but where the hell is Croft?

2007-04-13 12:36

To me, a Cardboard God post without any cardboard is like Oates without Hall, Garfunkel without Simon, Shields without Yarnell, Tony without Orlando and Dawn. It just doesn't feel right. Unfortunately, it'll probably be a couple days yet before I can resume my quest to autopsy my entire existence using my dull-edged 30-year-old baseball cards as scalpels. The wife and I are moving tomorrow, for the nine billionth time, and everything except a couple toothbrushes and the precious, precious television is taped up inside a box, including all the Cardboard Gods. (Luckily, anyone looking for a baseball card fix can tune into Bruce Markusen's fine portrait of Doc Medich on Bronx Banter today.) Also, for anybody in the Chicago area, below is some info about a fiction reading I'm taking part in next Friday. (I'll be reading from some non-basebally stuff about hippies and such.) WHO: Local writers and Vermont College alumni Carol Anshaw, Thomas Balazs, Jeanie Chung, Kate Harding, Bruce Stone and Josh Wilker WHAT: Reading to promote The Way We Knew It: Fiction from the first twenty-five years of the MFA in Writing Program at Vermont College and Hunger Mountain, Vermont College’s literary magazine. WHEN: Friday, April 20 5:30 p.m. WHERE: Barbara’s Bookstore 1218 S. Halsted Since its inception in 1981, the Vermont College Master of Fine Arts in Writing program has produced noted alumni including Anshaw and Wally Lamb. Each author will read from his or her work as it appears in the anthology. Anshaw, award-winning author of the novels Aquamarine, Seven Moves and Lucky in the Corner, and an instructor in the MFA in Writing Program at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, will emcee. Copies of the anthology will be available for purchase. Admission is free. Pepe Frias and Pepe Mangual

2007-04-11 04:40

Here are the only two Pepes in the entire history of major league baseball, poised on the brink of their team’s putrid 1976 season. The Era of the Two Pepes had begun in 1973, when 24-year-old Frias made a major league roster that already included 20-year-old Mangual, who’d broken baseball’s Pepe line by playing a few games the previous September. The versatile Frias, who could fill in for regulars at three infield positions and who (along with Otis Nixon) will be in the record books until the sun explodes as the most-used pinch-runner in Expos history (despite the apparent lack of speed suggested by his mere 12 career stolen bases), got into more games during the first two of the two-Pepe seasons, but then in 1975 Mangual took the lead in Pepe appearances by becoming the Expos’ everyday leadoff hitter. Mangual’s status as the top Pepe continued in 1976, but this seemed not to be a recipe for success as the Expos swiftly plummeted from longtime middle of the pack also-rans to a borderline entry into the discussion of the worst teams of all time. By the end of the 1976 season the Expos had dropped 107 games. Worse, all the losing spurred the increasingly desperate Expos to trade Pepe Mangual in midseason to the Mets, thus banishing the short brittle epoch of the Pepes to the dustheap of history. Yes, someday the sun will explode. I mean, right? I’m actually not too clear about all that, but certainly there’s got to be some kind of finite cosmic end date on our lease at this location. We’ll blow ourselves up, or drown in the rising ocean, or poison all our food, or get hit by a meteor, or sucked into a black hole, or else cockroaches will finally get sick of waiting around for us to hand over the keys, or the sun will burst or fizzle out or whatever it does when it gets tired of shining. So what’s this all about then? I mean, why are people rushing for the downtown number 6 train or getting haircuts or writing prose poems or keeping records for most times used as a pinch runner? At a certain point all of this will be completely erased from any kind of human consciousness, unless we build some kind of spaceship so sturdy that it can endure not only the annihilation of our neck of the woods but also the eventual collapse of the whole universe back into itself. And though I know there are some smart people among us, I sort of doubt this can happen. So the question remains, what to do with the time we do have here, this life of ours that is so rare it makes the appearance on a single team at the same time of the only two Pepes ever to play major league baseball seem no more unusual than a dandelion popping up at the edge of a suburban lawn. The fact that we’re alive is a miracle far beyond the far-fetched tale of the two Pepes. There’s no life anywhere else as far as anyone else has been able to see, just this one blue marble in the endless black. We’re the only ones breathing. It’s too much, really. I can’t really fathom it. I have to go watch some television. But first, just a few more words about the Pepes. The Pepes did not appear together in the Expos starting lineup with much regularity, but on one of the last occasions when the Expos went to battle with a two-Pepe attack (just a little over a week before the Mangual trade, perhaps not coincidentally), Larry Dierker of the Astros hung a no-hitter on the Canadian squad. The Expos had nearly been no-hit a month earlier, but Pepe Mangual broke up Andy Messersith’s bid with a one-out ninth-inning single. Three years later, Pepe Frias, no longer an Expo, was among the contributors to a hitless effort by the hapless Atlanta Braves against Ken Forsch. In that game he was pinch-hit for by cup-of-coffee pro Bob Beall, who would finish the season batting .133. In the earlier no-hitter Frias had been replaced at the plate late in the game by none other than Tim Foli, which is like having been bumped as a keynote speaker at the 1994 Conference for Clearly Enunciated Optimism in favor of Kurt Cobain. Tim Foli

2007-04-09 10:41

I. Ideal Versus Real The Mustache Ride crashes to a stop here with this fascinatingly awkward 1980 action photo featuring Tim Foli, Tim Foli’s no-frills "Shop Teacher" mustache, Tim Foli’s flat-topped Stargell-starred cap, and a sliding Joel Youngblood keeping the number 18 Mets jersey warm for Darryl Strawberry. Neither player is shown in a particularly good light. Foli, perhaps having flashbacks to the 1973 play when Bob Watson slid hard to disrupt Foli’s double-play relay throw and ended up breaking the shortstop’s jaw, recoils like a man about to be crushed by a teetering vending machine. Meanwhile, in pulling his right hand out of the way of a potentially harmful thrown ball, Joel Youngblood has inadvertently assumed a frightened, prone, unmistakenly effeminate pose worthy of Fay Wray. In all, the tableaux the two men create serves as a striking contrast to the idealized image of the leaping middle infielder gracefully completing the double-play relay (seen, for example, in the drawing in the lower-left corner of Kurt Bevacqua’s 1976 card). This play, in its ideal form, encapsulating all the skill and tension and suspense and ferocity and elegance of the game itself, is perhaps the single most emblematic image in all of baseball. I don’t know if they still do this, but when I was little Sports Illustrated seemed to always use a shining example of the play for the cover of their mid-World Series issue (which means it’s entirely possible that just a few months before this card came out Foli himself was, in a more acrobatic moment, the magazine's cover boy). So this photo, with its homely, bruise-producing, real-world corollary to the utopian baseball ideal, is a perfect place for the Mustache Ride to come to an end. Facial hair had entered baseball in 1972 as a symbol of a societal embrace of wider possibilities for individual freedom. My own family resided very near the psychic epicenter of the most hopeful, utopian leanings of that cultural trend, and by the time mustaches had spread onto the upper lips of major leaguers everywhere I was spending most of my days in a Sumerhill-inspired free school learning that I was "Free to Be" anything I wanted to be. Life, it seemed, was going to be a leaping dance move, a balletic double-play relay, a twirling kinetic ripple of bliss. But by 1980 I entered a standard junior high school and life started looking a lot more like the picture of Foli and Youngblood here: awkward, ugly, imminently painful. I did poorly in all my classes, but the one that I remember having the most trouble with was a shop class taught by a man with a mustache very similar to the one modeled above by Tim Foli. The final project was to build a metal tool box. I kept procrastinating, having little interest in the task and absolute certainty that I lacked the skills necessary to complete it. I didn’t want a toolbox. I didn’t need a toolbox. But soon the idea of the unbuilt toolbox filled my life with dread. This was what life was going to be like from now on. You are going to be asked to do things you don’t want to do and won’t know how to do. II. The Little Things Tim Foli compiled a .283 career on-base percentage and a .309 career slugging percentage, numbers bested by, among many, many others, utility infielder Mickey Morandini, utility infielder Mickey Klutts, and left-handed pitcher Mickey McDermott. Foli did however frequently rank among the league leaders in sacrifice hits and most at-bats per strikeout, traits that qualified him in the logic of the day (still currently in vogue in some quarters) as a prototypical "number two" hitter. (Note: though his numbers would suggest otherwise, the term "number two" is not in this context the well-known euphemism for the more redolent of the two standard bathroom excretions, but rather is a reference to the second position in a batting order.) The fact that the Pittsburgh Pirates became league champions in 1979 while using a lineup that most commonly began its assault on the opposition with the tepid one-two punch of Omar Moreno and Tim Foli is a testament to good fortune (both Moreno and Foli turned in career years at the plate with decent if nowhere near optimal on-base averages of .333 and .335, respectively) and to the redoubtable talents of the other Pirates. On the other hand, runs were harder to come by in those days, so I suppose Moreno’s blazing speed and Foli’s ability to bunt and hit behind the runner probably scratched out fiercely important runs once in a while in tense, low-scoring battles. Moreover, the estimable length of Foli’s career rebuts with great vehemence any arguments made by a superficially analytical stat-gazing ectomorph such as myself who wouldn’t be able to contribute even on the most infinitesimally slight level to a major league win if he had ten thousand years to try. Major league teams valued Tim Foli from the moment he was the first pick in the 1968 amateur draft (just ahead of Pete Broberg) to very near the end of his 15 years in the big leagues. I would guess that the Mets, who drafted him when they could have picked any other high school or college player in the country, were probably hoping for him to be a more potent hitter than he turned out to be, expectations which perhaps led to him being included in a 1972 trade to Montreal, but even after he showed the limits of his abilities as the Expos regular shortstop for years, the Mets chose to reacquire him in 1978, proving that they still saw him as a useful guy to have around. I don’t know how he fit in with the Pirates’ famously supportive and rousing "We Are Family" clubhouse vibe, but from my own (largely ineffective) athletic experiences I can say that it doesn’t ever hurt to have a guy on your side who’s ready and willing to start swinging whenever the need should arise. I never possessed this ability, but it seems clear that Tim Foli (nicknamed Crazy Horse for his "legendary tantrums," according to Bruce Markusen) did. One thing the photo in his 1980 card makes clear is that baseball, contrary to the more flowery appreciations by would-be bards of the diamond, is very much a contact sport. It helps to have a tough, ornery cuss in the center of the action. III. Shoe Store I started playing basketball in 1980, that year of metal toolbox dread. We lost every game, and the following year we only won twice, both against the same team, which got their vengeance the following year by contributing to our winless freshman team campaign. My coach in my freshman year was a guy in his early 20s who had played at our high school just a few years earlier. We saw him in general as a fairly nice guy who bowed to the dictates of the varsity coach, Viens (last seen in these pages casting aspersions on my Rollie Fingers-style Padres cap). My most vivid recollection of our coach’s Viens-puppeted behaviors is of when he ended one of our practices with a low, mumbling speech about how we weren’t fouling the opposition enough. He said that he and Viens had gone over the scoresheets from our games and we just weren’t committing enough fouls, a sure sign in their eyes that we weren’t being aggressive enough. Though it seemed even at the time to be an odd way to go about teaching us to be more aggressive, I remember that the speech produced in me the increasingly familiar feeling of dread that I’d experienced a couple years earlier with the metal toolbox project. I knew that if anybody was to blame for our low foul totals, it was me, and I also knew that I was incapable of changing into a careening Kurt Rambis-like human missile on the court: I was a coward when it came to physical pain. And this is what being a man was going to be like. You’re going to be asked to build metal toolboxes and foul guys. Anyway, that coach had a mustache. He was in the habit of touching the mustache with his lower lip, something I recognized years later in my short, abortive stabs at growing facial hair as the tic of a guy new to the feeling of having an unprecedented bristly mass on his face. He must have grown the mustache just before taking the job as JV and freshman basketball coach and high school gym teacher. I am guessing that he saw it as a symbolic step. He was a college student before, a kid, and now he was something else. Men had mustaches. He had a mustache. He was a man. His stay in the job was brief, just long enough to coach me and my hapless teammates for two years. Near the end of it he got a job elsewhere, outside the gym teacher racket. A friend had contacted him with an offer to help him run a new shoe store. As a child raised within the more idealistic currents of the 1970s, I have always had a lot of trouble trying to envision a practical future. Around the time of the toolbox, I gained at least a faint notion that I’d probably have to work for a living someday, but I never really got over the idea that I’d somehow be able to luck into a double-play relay-throw existence, a joyful pirouette. Instead I’ve fallen into one job or another, each one marked by my vague sense that there is something else out there. Davey Lopes

2007-04-07 07:18

When I was growing up I could never muster much enthusiasm for the Los Angeles Dodgers, even when they were the only thing standing in the way of the hated Yankees and another World Series crown. Their personification, Steve Garvey, struck me as a phony. Tommy Lasorda did too, but at least Lasorda projected, with the shifty unction of a snake oil salesman, the unsaid admission that on some level he knew he was full of shit. Garvey on the other hand actually seemed to believe he represented all that was right and true in the world. I think as an inward, bespectacled, unkempt, half-Jewish, girl-haired, Free to Be You and Me "It’s all right to cry" hippie-mothered dufus I sort of half-expected that at any moment the handsome, clean-cut, chisel-jawed, beamingly optimistic, flag-saluting Steve Garvey types of the world would decide to round up all us defectives and herd us into guarded barracks where we’d be forced to read unbearably boring DC Superman comics and watch Steve Garvey clinics on proper hygiene, obedient citizenship, and hitting the cutoff man. But on the other hand I always kind of liked Davey Lopes, shown here just moments after being dropped off at the ballpark by Cheech and Chong. I include Davey Lopes (or "Dave" Lopes as he is referred to here, perhaps as a tribute to the classic "Dave’s Not Here" routine by his addle-pated chauffeurs) as the penultimate chapter in the increasingly aimless, soon to collapse Mustache Ride saga for two reasons. Number 1, he’s one of those guys that I cannot picture without a mustache. And B, the dazed and confused expression he shows in this 1978 card in many ways communicates to me not only the tenor of the times but the particular way in which the vibrant hippie movement of the ’60s had become a burnt cinder by the Carter years. Throughout the 1970s baseball carried traces of the 1960s counterculture. To name three: the Kekich–Peterson wife swap, the no-hitter hurled by Dock Ellis while on acid (and a night of Jimi Hendrix records), the claim (for both its content and its sardonic, antiauthoritarian tone) by Bill Lee that he sprinkled marijuana on his pancakes every morning. But unlike the NBA, which featured a pony-tailed, bearded, Grateful Dead-befriending 7-foot redheaded vegetarian yeti with rumored connections to the famed Patty Hearst abduction case, major league baseball never provided a paycheck for the kind of fellow you might see hanging out in a Buddhist robe and sandals with Ram Dass and Allen Ginsberg at a Human Be-In reunion. Bill Lee was perhaps the closest thing, but he was really more an eccentric libertarian iconoclast than a member of any explicit or implicit movement; also, the closest he ever came to looking like a hippie was during the latter stages of his tenure with the Expos, when his gray-flecked beard made him resemble the 30-something former hippies he would soon be living among in his retirement in rural Vermont. But what baseball did have in the 1970s, especially during its Carterian dregs, was a lot of guys who, as with Davey Lopes here, looked as if they might have a couple "lids" of "grass" back at their "pad." All across America young men with mustaches were stumbling through their lives with cannabis in their bloodstream and corporate Rock songs stuck in their head. Gone were the days when the drugs and the music seemed to herald the opening of heaven on earth. Now it was all about trying to hold down a job to make payments on the customized van and, whenever possible, getting fucked up. "Don't look back," went one of the corporate Rock songs stuck in the heads of these young mustachioed hearty-partying men. "All we are is dust in the wind," went another. Paul Lindblad

2007-04-05 04:35

Paul Lindblad Ponders Growing a Mustache, 1975 Paul Lindblad was a top middle reliever for many years in the American League. He is shown here after helping the A’s win their third straight World Championship by posting the best ERA of his career, 2.06. Just below the stat line with that information is a (somehow fittingly) terse textual note further attesting to Paul Lindblad’s capabilities: "Paul had 0.00 E.R.A. in 1973 series." For some reason I’m inclined to believe he plied his trade with very little ego. He certainly seems in this photo to be far from displaying the air of complacent self-congratulation that supposedly has a tendency to infect members of a championship squad. But I really don’t know much about Paul Lindblad. Before becoming fascinated over the last few weeks by his expression on this card, my only connection with him beyond a vague appreciation of his membership in Oakland’s outstanding relief corps was my own tic-like predilection as a child for saying aloud his unusual last name, which probably seemed to my Mad Magazine-devouring mind like one of the spelled-out sound effects in a Don Martin cartoon. To this connection I can only add the fresh shock of just finding out, while casting around for more information on the man with the arrestingly troubled mien, that Paul Lindblad died in 2006 (see Catfish Stew). His page on baseball-reference.com now has a death date, as well as an epitaph in the sponsor section, supplied by someone named Wolfie: "Lindy: Quite simply, one of the best guys ever to put on a uniform." I’m inclined to believe those words, but then again you can’t be much more of a baseball outsider than me, so all I can really add to the story of Paul Lindblad is the trivial, groundless, ridiculous belief that in the photo shown above he is trying to decide if he should finally grow a mustache. The hoopla that such an act might have once created is long gone, this card coming out three years after the A’s broke the baseball facial hair line in 1972. Not coincidentally, Paul Lindblad, after spending several years with the A’s prior to 1972, had been toiling for the Rangers that pivotal year, and by the time he returned to the A’s the hippie-lip revolution had already occurred. In fact, by 1975, players on all teams save for some last holdouts (such as Cincinnati), where conservative grooming codes continued to strain against the grain of the times, were busting out beards and mustaches, muttonchops and fu manchus. To have a mustache was no longer in any way a declaration of independence. It was merely a personal choice. And this is exactly when the world got confusing. This is exactly when the 1970s truly became the Me Decade. Everyone was on their own to make their own choices about everything. Grow a mustache, don’t grow a mustache. Do your own thing, don’t do your own thing. Who cares? No one. You’re on your own.

Like its immediate predecessor, this 1976 card also has one brief line of text on the back side, at the bottom, below the impressively long block of statistics listing all the years he’s been in the league on the left and all his stingy earned run averages on the right: While his stalwart professionalism is on display on the back of the card, the front of the card shows that he has yet to decide the quandary that has been on his mind since at least 1975. His upper lip remains bare, suggesting that he decided in the negative, but his expressive eyes overrule this suggestion, making clear that the matter remains unresolved. If anything, Paul Lindblad seems even more undecided. He is a year older, a fact that seems to register almost imperceptibly in his somehow slightly less ruddy features, and he seems to have grown a little more melancholy. The featureless blue sky behind him, where the year before there had been the sheltering embrace of a ballpark, adds to the feeling that Paul Lindblad is a little more alone this year than he was the year before. Many of the championship A’s are still around, but they won’t be for long. And the biggest, loudest A of all, Reggie, has moved on. In the ensuing silence, Paul Lindblad continues to ponder.

My father once told me that one thing that helped get him through the 1970s was his work. It wasn’t his happiest epoch. As suggested in the previous chapter’s description of my family’s early-’70s living arrangement, he began the Me Decade by going to unusual lengths to remain part of an "us." After a couple of years of the ultimately aborted experiment in open marriage, he spent the rest of the decade living in a studio apartment in Manhattan while his family lived several hours away by Greyhound bus, in Vermont. This had to have been painful. But he had his work. He was a sociologist, for most of that decade a project leader on a research team charged with a massive evaluation of the effects of city services on all levels of the population. He threw himself into his work, as the saying goes, but quietly, selflessly. He was a Paul Lindblad type. He showed up day in and day out in a way that not only benefited the project he was working on but that helped feed much-needed money to the frequently imperiled utopian dream of his distanced immediate family. He wore a mustache for some of that decade. But this facial hair was never part of some rousing movement, large or small, like the swashbuckling 1972 A’s or the "let that freak flag fly" hippies. I have referred to it elsewhere as hair shrapnel, a piece of the general hairiness of the culture of the time that seemed to have landed randomly on my dad’s face. I don’t know if I got that right, however, for he had indeed made a decision to grow a mustache, and he had made it alone. He had then worn the mustache for some years. And then, in another solitary decision, he had chosen to remove the mustache. I can see him shaving it off one evening in the bathroom of his apartment, then leaving the bathroom to unroll his foam sleeping mat on the floor below the one window, going to sleep, getting up the next day, and going to work. "I absorbed myself in my work," he once told me, speaking of the entire 1970s. As for Paul Lindblad, he is shown here still in the midst of his own increasingly solitary and still unresolved decision. The Topps people, perhaps attempting to dim the increasing pathos of another close-up of Paul Lindblad’s undecided face, have placed him in his workplace. This serves to distance the viewer from his face, but it also seems to lighten the expression ever so slightly, Lindblad not wrapped up quite so much in his unresolved solitary decision, instead able to put himself into the working mind he has been so adept at becoming absorbed in since breaking into the league over a decade earlier. Still, there is ample evidence that Paul Lindblad still has things on his mind. He has by now been left behind by most of the championship A’s. He perhaps senses that the end in Oakland is coming for him too. In fact, by the time I found this card in a 1977 pack, Paul Lindblad had been sold to the Texas Rangers. In such a world where the very ground can be pulled from beneath you, when your team can be taken away, when your family can be taken away, when the job you throw yourself into can be lost (my father, after spending years on the research project, lost his job near the end of the decade by the abrupt end of funding for the project, all the research halted before any conclusions could be reported), certain personal choices turn out to be all you really have left. They are the only thing you can control. And yet, they are pointless, absurd. To grow a mustache or not to grow a mustache, that is the question. The implied answer—what’s the difference?—lingers on the horizon like some kind of soundless cosmic tornado with the power to strip your world of all meaning.

When I found out that Paul Lindblad had died, I also found out that through the last decade or so of his life he suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, that gradual, inexorable cosmic tornado. He is shown here on the brink of the 1978 season, his last in the major leagues. He started the year with the Rangers but was purchased by the surging Yankees late in the season. For what it’s worth, his last official moment in a major league uniform was as a participant in a world championship celebration. Rollie Fingers

2007-04-03 06:02

In 1969, my mother met a young man with facial hair. She was riding by herself on a bus to a peace march, her clean-cut husband at home with my brother and me. I think the facial hair on the young man amounted to a scruffy week-old growth, but that fledgling beard, along with his round wire-rim glasses (like those made notorious at that time by John Lennon) and other similarly-themed sartorial details that I am not exactly sure of (but that I have, in my endless compulsive imagining and reimagining of the moment, nonetheless guessed at: shoulder-length hair, a bristly wool poncho, a lopsided homemade corduroy cap, maybe some sort of necklace medallion purportedly imbued with shamanic powers) communicated membership in that loose-knit tribe of young, predominantly white men and women that was either (depending on your viewpoint) breathing joyous new life into a stagnating, death-bent, unjust world or trampling the norms and values of common decency and traitorously undermining the stability of American democracy. In other words, my mom met a hippie. Previous to the peace march, while chained to a toddler and a fat, wailing baby in a generic suburban housing unit, my mom had begun romanticizing the exploits and lifestyles and passions of these young people. She was not alone. Today the idea of the hippie has been reduced to a comical stereotype: the unshowered space cadet in the broken-down Day-Glo VW bus, the starry-eyed, sloganeering peace-and-love simpleton, the brain-fried anachronistic acid casualty, confused by and/or oblivious to any cultural or technological advances occurring after the deaths of Janis, Jim, and Jimi. But in 1969 hippies were a potent cultural force that seemed capable—to both those who romanticized them and those who feared and loathed them—of changing the world. For my mother, I think they also represented the life she had always hoped to live, a life of meaning, community, significance, and, most of all, passion. She signed up to ride the charter bus to the peace march because she wanted the Vietnam War to end, but also because she wanted to become part of the colorful world she was romanticizing. In my novel, The Kappus Experiment Sings, the fictional character inspired by my mother talks about this growing desire to "get on the bus" in the months leading up to the peace march:

So that was 1969. Let’s jump ahead to 1972, the year the Oakland A’s, with Reggie Jackson in the lead, shattered baseball’s long-held clean-cut look. I was four years old, still oblivious to baseball, and living in a house with my brother, mother, father, and Tom, the man my mother had met on the bus to the peace march. (Hippies. Love them or hate them, it seems to me you have to at least admit they swung for the fences.)

Now let’s jump ahead some more, to 1978. That's the year this card became property of my 10-year-old self. By now the family, which had moved from New Jersey to rural Vermont four years earlier, had morphed back into something approximating the nuclear family norm, albeit with Tom in the father slot and my dad an occasional visitor from his apartment in Manhattan. The family, minus Dad, had moved to Vermont with hopes (at least among the two attending adults) of attaining a utopian rural self-sufficiency. My mom was going to grow all our food, and Tom was going to be a roving blacksmith. He installed a small forge in a used Dodge van, cutting a hole in the roof of the van for a peaked metal chimney. The kids of East Randolph, Vermont, thought this implied the van ran by the burning of wood, an idea that they worked into the arsenal of mockery they aimed at us. I imagine the farmers Tom was hoping to have as clients had a similarly withering view of the unorthodox van, if not also of the unorthodox longhaired, long-bearded blacksmith; either way, he was never able to drum up much business. After a few years the back-to-the-land dreams faltered substantially in the face of one small disheartening crisis after another, like a dead-of-winter car repair bill overmatching a paltry bank account built on the occasional sale of a fireplace poker that Tom had hammered into shape on his blacksmith anvil. By 1978, both Tom and my mother had given up on total self-sufficiency and gotten regular jobs. I imagine the late 1970s for Mom and Tom and other former hippies and weary back-to-the-landers as a somewhat anticlimactic, diasporic time. Because I relate everything to baseball, I see this miasma as something akin to what the scattered members of the ’72–’74 championship A’s were experiencing at the same time. The early ’70s had been a turbulent, exciting time in which they had banded together against a hated authority figure (Charlie O. Finley), and come out on top for what was one of the most extended periods of triumph (and undoubtedly the most colorful of such periods) in baseball history. Similarly, Mom and Tom and the people they identified with felt that they were rejecting the idiotic edicts of a corrupt despot named Nixon to stake their own claim to a golden life. And while they never quite got there, in retrospect it always seemed that those woozy, careening, love-drunk years were something of a championship run. And now there was a feeling of being spread out and scattered. For Mom and Tom this feeling was hard to define, more just a sense that they were on their own now, not part of some movement with great uplifting momentum. For the A’s the scattering was literal: Bando to Milwaukee, Campaneris to Texas, Reggie, after a stop in Baltimore, fittingly reunited with the limelight in New York, Catfish there with him but fading into the polluted sunset, Rudi on the Angels, Blue on the Giants, etc., etc. The most symbolic exile of all, for both the way he symbolized the strident zeitgeist-embracing look of the dynastic A’s and for the nauseously drab brown and yellow anonymity of his new surroundings, was Rollie Fingers, shown in the 1978 card at the top of this page displaying a pitching grip with what seems to be an expression of tentative, nervous supplication, as if he is hoping the expert grip will somehow gain him a release from the exile of toiling onward in obscurity with the 93-loss Padres. But of course this is not the first thing you notice about the photograph. The first thing you notice is the very thing that Rollie Fingers had most in common in 1978 with the man my mother had met on a peace march almost ten years earlier. The mustache. Of all the A’s, only Rollie Fingers fully carried his essential A-ness with him into the wandering years. The A’s had been an excellent, superbly well-rounded team, but they had also been an iconoclastic emblem of the times. Rollie, who would gain entry into the hall of fame on the strength of his pitching, remained a living monument to both aspects of the Swingin' A's. As for Tom, his entry into the 9-to-5 world signaled the final goodbye to the long hair and the wildman beard, which had been in remission for some time, but in their place now was a Rollie Fingersesque handlebar mustache. "The times are never so bad that a good man cannot live in them," St. Thomas once said. And the times are never so deflated and drab that a spirited man cannot fight against them with a mustache that curls up at both ends. Go forward some more to 1982. Tom’s job in the company had changed from customer service to dealer rep, and he had begun traveling all over the country to visit stores that sold his company’s wood stove. I’m not really sure why there was a wood stove store in San Diego (maybe there was an industry conference there), but on a trip out there Tom brought back a San Diego Padres cap for me that closely resembled the one on Rollie Fingers’ head in the 1978 card. Rollie Fingers himself had moved on by then to the Milwaukee Brewers, and my family was on the brink of going its separate ways. One day I wore the cap into the high school where I was a freshman with bad grades and no extracurricular activities besides participating sparingly in brutal junior varsity basketball defeats. The varsity basketball coach, Viens, saw me wearing the cap in the hall. He’d never said anything to me before. He stopped me and squinted up at the cap. He wore a tie and a short-sleeve button-down shirt. "The Padres?" he said, his upper lip curled. He had short hair. A clean-cut face. "Why in hell would you want to wear something from the Padres?" "I don’t know," I said. I took the cap off and looked at it. It was different. It was from somewhere far away. And Tom had gotten it for me. I wasn’t able to verbalize any of this. "Losers," Viens said and walked away. Reggie Jackson

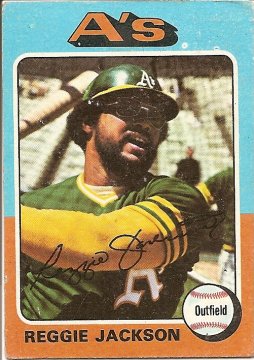

2007-04-01 10:33

The Mustache Ride, Chapter 1 The Mustache Ride, Chapter 1I’ve written about Reggie Jackson before in my ongoing effort to view the aimless stumble of my life through the prism of the baseball cards I collected from 1975–1980. But if anybody from that time is going to demand more than one look, it’s the hirsute extrovert pictured here. Though I have known for a while that the core player of this wandering narrative, for personal reasons, is Carl Yastrzemski (so far seen only in glimpses), I understand that Reggie Jackson was, objectively speaking (or Reggie speaking), the loud and proud center of the inimitable toxic Technicolor disco inferno that was baseball in the miasma of the Ford and Carter years. He may even have been the best player. I had it in my mind that Joe Morgan and Fred Lynn outperformed Reggie during that span, but on closer look both of those players, though as fielders far more useful to their teams than Reggie, actually had a couple of subpar, injury-hampered years at the bat while Reggie pretty much kept mashing year in and year out. Probably only Jim Rice was as consistently fearsome a hitter as Reggie during my childhood years, but even I have to admit that my beloved Jim Ed had the benefit of playing in the best hitters park in the league. And on top of all that Reggie was Mr. October, the successor to Bob Gibson as baseball’s king of the big stage. But when I imply that all Cardboard God roads lead to Reggie I’m not just talking about performance. Though baseball has never been a hermetically sealed world unto itself, it seems to have embodied the times during the 1970s with an abandon never seen before or since, seething and sparkling and belching and flailing with all the careening spasms of the Me Decade. And nobody epitomized this more than Reggie, the candy bar that told you how good it was when you unwrapped it, the walking 60-point tabloid headline, the one-man neverending tickertape parade. The man just couldn’t not be The Show. Take this card. The empty stands and the presence of a teammate casually loitering nearby identifies this photograph as one not taken during a game. My guess is that the Topps photographer came to the park that day planning to capture Reggie with another of the strangely lifeless "still life with bat" shots that riddle the card collections of that era (for a typical example of this from the same year, see Mario Guerrero’s 1975 card). But Reggie Jackson simply could not be contained. Every part of him, from his bright yellow superhero-muscled forearm to his Steve Austin aviator shades to his wide open ever-motoring mouth, radiates crackling, kinetic life. All he’s doing is lazily swinging a bat, and it’s riveting. Even I have to admit this, and (as perhaps suggested in a previous Cardboard God profile that heaped potentially libelous anti-capitalist invective on Reggie) I spent the last tender years of childhood coiled with hatred for the self-professed straw that stirred my least favorite drink, the Yankees. While I can't say that I have a connection to Reggie as deep as the one described by fellow late-'70s child Alex Belth in his moving essay in Bombers Broadside 2007, I do owe him a debt for his big-ass way of being, which made the world a wider, more exciting place to be. It's no accident that the only thing I remember from the first baseball game I ever went to, in 1975, besides my first glimpse of the grass at Fenway, is that Reggie Jackson was in the house. He had the ability to make anything he was involved in The Main Event. |