|

Monthly archives: March 2008

Gorman Thomas, 1975

2008-03-30 14:34

Here we see Gorman Thomas in something of a "before" picture, not yet featuring his drooping, malevolent horseshoe mustache. He still looks like a pretty rough customer, though. According to the back of this card, during the previous season, in Sacramento, he launched 51 home runs in just 474 at bats. This being a 1975 card, there is also a trivia question on the back, a pretty easy one: "What was Mickey Mantle's uniform number?" But the front of the card seems to suggest a trivia question about uniform numbers, too. Anybody want to take a stab at what that question might be? Ivan DeJesus

2008-03-29 08:44

I was twice ordered to bunt in what turned out to be the final game of my baseball career. I was 14 and on a terrible Babe Ruth team that got worse as the season wore on. But we eventually found a team even worse than us, probably the same ragged collection of hippie teens that my brother almost no-hit the year before. We got a good lead early, yet when I came to bat our coach gave me the sign from the third base coach’s box to lay down a bunt. In retrospect I think he was trying to let me know that my opinion of myself as a baseball player, which I’d formed while doing pretty well in Little League, was outdated. I was a scrub now, a bench guy. I wasn't as happy to throw away my at-bat as Ivan DeJesus appears to be, but I followed orders and laid down a good bunt. The coach never acknowledged it. By my next time up we were really pounding them. Everyone had gotten into the fun but me. I looked up the third base line to the coach and he touched his belt again, the bunt sign. I couldn’t figure out if he was an idiot or if he was punishing me. Either way, I was through with baseball. I lashed a double, probably my only solid hit since Little League. As I stood on second base I didn’t look at the coach. My body tingled from making good contact. The first true love of my life had ended. * * * (Love versus Hate update: Ivan DeJesus's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Barry Bonnell

2008-03-27 04:53

* * * Ron Guidry

2008-03-25 11:09

When I was a boy I was afraid to bicycle past a Doberman pinscher who was, according to the kid who owned him, so fierce that it often chewed through its chain and went on bloodthirsty rampages. I was afraid of the night terrors that tore me from sleep and sent me screaming through the house. I was afraid of ending up in a situation where I would be forced to eat fruit. I was afraid of death. I was afraid of bullies. I was afraid of girls. I was afraid of our basement. After I saw The Shining I was afraid of our bathtub. I was afraid of the three-note Duracell ditty that ended with the sectioned battery slamming together. I was afraid of nuclear bombs. You could be sitting there on the floor of your room, sorting your newest baseball cards into their respective teams, and it could all vanish in one bright flash. I was afraid of everything ending. In light of all those fears, I can’t really say that I was afraid of Ron Guidry. I mean, I wasn’t afraid Ron Guidry was going to leap out from behind a snowbank and bash me with a rock. I wasn’t afraid Ron Guidry was going to force me to touch my tongue to a frozen metal pole. I wasn’t afraid Ron Guidry was going to burn our house down. And yet, when I hold this 1979 Ron Guidry card in my hand, even thirty years after he went 25-3 with a 1.74 ERA—numbers so astounding they seem inhuman, merciless, obsidian, obscene—to lead the 100-win Yankees past my team, the 99-win Red Sox, it’s as if I’m holding a small box made of thin, fragile glass, a scorpion inside. Bucks 1980-81 Team Leaders

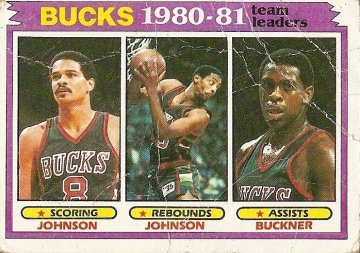

2008-03-21 09:36

I never remember any new moments anymore. Take the NCAA basketball tournament. Every year I throw myself with abandon (i.e., sit and eat and stare at a television for hours at a time, clutching my disintegrating bracket) into March Madness, especially its first couple days, and every year I almost instantly forget who did what to whom. I sort of remember Vermont upsetting Syracuse a few years ago, but that’s because I grew up in Vermont and because when the final buzzer sounded I leapt up from the couch and bashed my knee on the coffee table, which really hurt. Other than that, it’s all a Mopa-Njila-tinged haze. Yesterday, had Belmont pulled off the upset of Duke, I would have again leapt up from the couch, taking care not to bash my knee on the coffee table, and I would have bounded around my living room shouting and laughing and high-fiving myself. But probably by next year only the vaguest memory would remain. At the very end of this year’s tournament, when CBS plays the song "One Shining Moment" behind a video montage of tournament heroics, it’ll be for me like watching files get moved across a computer screen to the Recycle Bin, where they’ll remain until automated deletion. I’ve got no more room in my brain for Shining Moments. And yet, after all these years, even though I probably never saw them play, I can name eight or nine members of the 1980-81 Milwaukee Bucks without even turning over this card. Swen Nater

2008-03-20 06:45

I don’t know. It depends. A guy who wishes he could build a fort out of couch cushions. A guy ready to spend the next four days dissolved in a solution of basketball. A guy looking back. A few years later I was in college. I decided to try out for the college team. Who was I? Where was I? I was a basketball player in America. It was 1988. At the top of the basketball world in America in 1988 was Magic Johnson. Magic Johnson was the star of the Los Angeles Lakers. The Los Angeles Lakers were the champions of the National Basketball Association. There was some minor league basketball being played in America in 1988, but the most talented players in America not playing in the NBA were in college. College basketball was divided into many levels. At the top level was Division I of the NCAA. There were then, as now, many conferences in Division I, some better than others, each conference with its own smaller internal hierarchy, each individual team with its own even smaller individual hierarchy. At the very top of the mountain of NCAA Division I basketball that year was Danny Manning, star of the National Champion Kansas Jayhawks. I don’t know who was at the very bottom of the hierarchy of NCAA Division I basketball, because easily accessed records are not kept on the worst player on the worst team in the worst conference of NCAA Division I basketball. But I do know that below NCAA Division I basketball is NCAA Division II basketball. I don’t know who was at the top or bottom of that organization of conferences and teams and players. I can however tell you that below NCAA Division II basketball is NCAA Division III basketball. And below all three divisions of NCAA basketball is the NAIA. I’m not sure what NAIA stands for. But it is a college basketball federation that has its own hierarchy of conferences and teams and players. Some good players have come out of the NAIA, such as He of the Blond Perm of Unmatched Magnificence (Jack Sikma) and Scottie Pippen. They most likely played on the best teams in a top conference in the NAIA. But this isn’t about them. In 1988 the worst conference in the NAIA was the Mayflower Conference, a small collection of little-known state-funded schools in northern New England, that regional hotbed of skywalking, rim-rattling basketball talent. The worst team in the Mayflower Conference, by far, was the Johnson State Badgers. The Johnson State Badgers employed an unorthodox roster configuration that designated 10 players as team members in full and six other members as “alternates.” The alternates took turns suiting up in the remaining two team uniforms, two alternates for each game. A few games into the fruitless season, all but one of the alternates had gotten some end-of-humiliating-blowout playing time. This final alternate accompanied the team to a game in Plattsburgh, New York. The outcome of the game was never really in doubt, but somehow the Badgers managed to keep the game from being a rout, which of course made it impossible to insert the final alternate into the game. With a couple minutes left in the fourth quarter, the Badgers somehow still weren't without a slim hope for a miracle comeback. Their first- (and last-) year coach, a befuddled English teacher, realized that the only chance for such a victory hinged on the old strategy of sending the other team to the foul line and hoping they missed. He identified the opposing player most likely to clank free throws and started shouting at the guy guarding him. “Luneau, foul number 32!” he shouted. “Luneau! Luneau! Foul 32!” Luneau either didn’t hear or didn’t want to hear, and merely kept trying to play tough defense. He was a good player. He had his limitations, to be sure, but he was a good scorer and a relentless offensive rebounder. He was certainly not the worst player in the world. He had his pride. “Luneau! Luneau! Foul 32!” The English teacher’s voice had begun to crack. The gym was mostly empty, so his pleading could easily be heard above the bouncing basketball and the squeaking of sneakers on the floor. Finally he spun away from the action in disgust and looked at the players seated behind him on the bench. He spotted the last alternate. “Wilker,” he said. “Get in there and foul 32.” Tom Hilgendorf

2008-03-18 14:04

This is the last of a few Tom Hilgendorf cards of negligible worth. He was cut by the Phillies the year it came out, right around when the team broke camp. It’s something of a mystery why this cut was made, as Hilgendorf had done well the previous season, posting a 2.14 ERA in 96 innings of work. Maybe the Phillies felt they had enough left-handed pitching, with newly acquired Jim Kaat joining Steve Carlton and Tom Underwood in the rotation and Tug McGraw anchoring the bullpen. Or maybe Hilgendorf just lost it that spring. Maybe he just couldn’t get anybody out all of a sudden. I couldn't get out of bed this morning. When my alarm clock went off my first conscious feeling was shame. Vague, general shame. The day before had been a waste, yet again. I’m now older than all but a handful of current major leaguers, yet on some level I still think of myself as the kid and the players as the adults. It’s becoming less this way as the years go by, however. While cheering on the Red Sox this past season I understood that it made all the sense in the world that Jonathan Papelbon, for example, was not even born when I played my last little league game. Where I find it more difficult is when I look at these cards and realize these examples of adulthood are all younger than I am now. These were always the adults. I understand how I can be older than a kid who Riverdances all over the infield in his red underwear, but how can I be older than the Cardboard Gods? At the time of this picture, Tom Hilgendorf--frumpy, expendable Tom Hilgendorf--was several years younger than I am now. My alarm clock is tuned to the sports radio station. I start every day with the sounds of Mike shouting at Mike, or vice versa. This morning I turned off the alarm clock and lay there in the dark. I wish I could build a fort out of couch cushions and stay there forever. Eventually I got up and fed the cats and shoved food down me and made a sandwich and walked up Western Avenue in the drizzle and bought a newspaper to get some tips on filling out my NCAA bracket and heard the elevated train coming as I passed through the turnstile and bounded up the concrete steps two at a time and made it in just before the doors closed and sat there breathing hard and sweating and made it to work on time. Jim Palmer

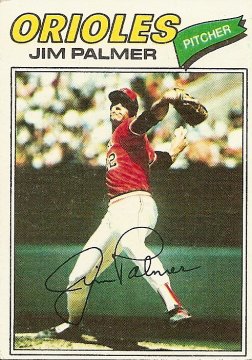

2008-03-17 09:23

My first roommate, besides my brother, was a pimply kid from Baltimore. I got assigned to him randomly when I went away to boarding school. I was fifteen. He was into computers. In fact, he had somehow built his own computer. This was in 1983, so he was ahead of the curve on that one. He didn’t have any posters but covered his walls with random things from his life. I never looked too closely, but I remember a broken calculator as being one of the things hanging on his wall. There were papers, notes, drawings, scraps from magazines. He was a smart kid, a dweeb. He played Dungeons and Dragons. Like many of the dweebs, he was simultaneously awkward and arrogant, and he had a weird but OK-looking girlfriend. We got along pretty well. He drank a Coke before going to sleep every night, claiming that it always knocked him out. He was the only Jethro Tull fan I've ever known. He was a rich kid, I guess. I've always figured that he went on to make a lot of money in computers. His mother dated Jim Palmer for a while and he and Jim Palmer once played racquetball. Jim Palmer reached the major leagues at age 19 and capped his first full major league season the following year by ruining Sandy Koufax’s final game, beating Koufax 6-0 in Game 2 of the 1966 World Series. Palmer had not yet turned 21. He spent most of the next two years injured or in the minors, the Orioles not able to contend without him, and when he came back to stay in 1969 the Orioles won three straight American League pennants. So in Palmer’s first four full seasons in the majors, his team won four American League pennants and two World Series titles. Though things slowed down a little after that, he still was able to add four more division titles, two more pennants, and one more World Series ring to a trophy case that also included three Cy Young awards. In addition, he racked up more wins in the 1970s than any other pitcher. I’m tired, timid, empty. It took me a long time to get out of bed. Unwrap each day like a precious gift, I thought to myself as I lay there under the blankets, unable to move. I guess later I’ll go buy a paper and scrutinize the NCAA basketball bracket. So far today I’ve written in my notebook, listened to sports radio, eaten some saltines, and tried to figure out which World Series game included the most Hall of Famers. I started investigating the subject after seeing that Jim Palmer won a game in relief against the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1983 World Series. The losing pitcher, Steve Carlton, is a Hall of Famer, as are three of his Phillies teammates (Joe Morgan, Tony Perez, Mike Schmidt) and two of Palmer’s fellow Orioles (Cal Ripken and Eddie Murray). Since obvious Hall of Fame-caliber player Pete Rose also pinch-hit in that game for the Phillies, I gave the game a total score of 7* with the asterisk standing for Rose, and then started scanning through likely contenders on the baseball-reference.com postseason index. I eventually found a World Series game that featured nine Hall of Famers (plus an additional Hall of Famer if you count managers). I feel fairly confident that this is the record (author update: it's not), but my search was inexhaustive and reliant on hunches, so please correct me if I’m wrong (author update: someone did; see comments). But let's just say I'm right. Can you name the year and the teams and Hall of Famers involved? Finally, to end this lackadaisical meander of a post, let me again throw out the trivia question from a comment I attached the last post, copying it from the back of Bob Coluccio’s card ("Which pitcher sang National Anthem at ’73 World Series?"). Hint: the player once contributed to a World Series defeat of Jim Palmer’s Orioles and then later wrapped up his career as Palmer’s teammate. Bob Coluccio

2008-03-14 06:18

I should have tried harder. I should have paid more attention. I should have gotten laid more in college. I should have been a beginner more often. I should have not been so serious all the time. I should have gotten over my fear of ostriches. I should have struck up more conversations with strangers. I should have brushed more thoroughly and flossed once in a while. I should have made enough money to buy my aging parents a house. I should have made enough money not to have to hit up my aging parents for a loan that one time when my year in the cabin came to an end with me in abject poverty. I should have made better use of my year in the cabin, becoming pure or something instead of just a little lonelier and poorer and maybe a little more aware of the silence at the heart of everything. I should have given up the world of what if, the world of someday, and worked as hard as I could every day, like my immigrant ancestors, those short gray toilers who sacrificed themselves for the future of their family, i.e., dreaming, lazing, napping me. I should have just started writing whatever came to mind and pushed it as far as I could and discovered undiscovered lands within or something instead of trying to mimic my literary heroes with every timid word. I should have volunteered at the homeless shelter or participated in voter registration drives or taught some fatherless kid to shoot a jump shot. I should have become a teacher early on and taken my lumps and hung with it. I should have just left Marv Albert alone that time at the airport. I should have not said all the stupid things I said. I should have said other things. I should have said nothing. I should have sung. Major League Leading Firemen, 1975

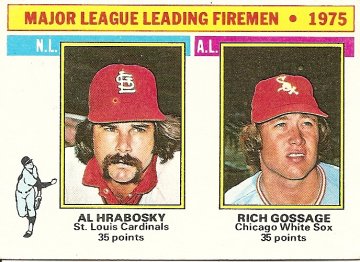

2008-03-12 14:00

If the history of star relief pitchers was the history of rock and roll, this card might be something like a snapshot taken of two young duck-tailed hep cats at Sun Records in 1954. Each moment in question has rich historical roots, antecedents such as Hoyt Wilhelm and Firpo Marberry and Dick “The Monster” Radatz feeding into one story as Robert Johnson and Bill Monroe and Big Joe Turner feed into the other. But with Sun Records, 1954, and Major League Leading Firemen, 1975, the histories are poised to become something all their own, to catch fire. In this analogy, Al Hrabosky would be Carl Perkins, the pioneer of a savage new style that would bring him a brief, hot fame that would fade, leaving him years later largely forgotten by the general populace. And Goose would be Elvis, the one-name star who in some ways absorbed the style of his daring contemporary on his way to prolonged success and widespread immortality. Just as Carl Perkins was first and therefore most striking to snarl the threat not to step on his blue suede shoes, Al Hrabosky was first to close out games with motorcycle gang facial hair and the bristling malevolence of a starving caveman bent on breaking the neck of and feeding on a saber-toothed tiger. As a kid I was mesmerized and a little scared by the images on This Week in Baseball of Hrabosky stomping around behind the mound before pitches and shouting and gesticulating after pitches. But the key to his brief, hot fame--as with Carl Perkins--was that he was, at least briefly, really good. In fact, as good as Rich "Not Yet Goose" Gossage was in 1975, Al “The Mad Hungarian” Hrabosky was probably a little better. In 1976, when this card commemorating their success (albeit with a points system that was not explained and that few understood) came out, Hrabosky fell back to earth, but not as much as Gossage, who was moved from the bullpen to the starting rotation, where he floundered, posting a 9 and 17 record. At that point, if you had told a casual baseball fan that one of these men would someday make the Hall of Fame while the other would fade into relative anonymity (as evidenced by his unsponsored $10 page on baseball-reference.com), the casual baseball fan probably would have guessed that Hrabosky, not Goose, would be going to Graceland. Love versus Hate

2008-03-11 12:33

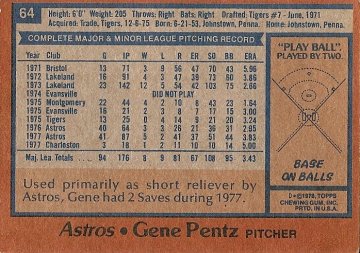

Pregame notes: When I was a kid I was always looking for a way to dissolve into made-up worlds. That I never tried “Play Ball,” which was part of the back of each 1978 Topps baseball card, doesn’t reflect well on the game. If an isolated, day-dreaming, baseball-loving, baseball-card-collecting kid didn’t play the game, who the hell would? But in retrospect I applaud the inclusion of the game, as it suggested that the cards were not to be sealed under protective plastic—a trend that took hold on a widespread basis after my years of collecting—but to be touched and handled and played with. So I’ll play. Thirty years later, I'll play. Below are the rules, courtesy of one of the 1978 cards previously profiled on Cardboard Gods. (Pregame Trivia Question: Can you name the player featured on the rule-giving card?) I will be breaking the primary rule ("Played by two") by playing solitaire. I will also ignore the coin toss rule. I know which of my imaginary teams is the home team and don't need a coin toss to tell me. I will describe the action in a running line-score below. The outcome of each at-bat is followed by the parenthetical listing of the player whose card provided the outcome. I think it’s important to keep in mind when perusing the results below that the players listed are not participants in the imagined game but the gods that determine the path of that game. The cards are all 1978 cards that have been profiled on Cardboard Gods; the earlier cards have been jostled from their chronological order and appear randomly (some time ago when I was leafing through my stack of written-about cards I dropped them and they scattered all over the floor), while the more recent ones were pulled from the pile in the order they appeared on this site. Now, with all that out of the way, please rise for the singing of This Land Is Your Land. Thank you. Play Ball! Top of First, Hate Batting, Tied 0-0 Bottom of First, Love Batting, Tied 0-0 First inning notes: I want to talk about the team names, but first let me say how pleased I am that the trio of gods delivering the first runs of the game for Love are Pete LaCock, Lenny Randle, and Bill Buckner. Who better? Anyway, when I was a kid my made-up games often involved the development of entire leagues populated by teams filled with individual personalities. But occasionally I kept it simpler. I once spent hours playing handball in our living room with a balloon, and I never developed the imagined entities in opposition to one another beyond “left hand versus right hand.” I based the naming of the two teams battling it out in my enactment of “Play Ball” on that lackluster afternoon’s battle between hands and on the memorable monologues on the very same battle by the Robert Mitchum character in Night of the Hunter and Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing. Here’s the latter character's version of the speech: Let me tell you the story of “Right Hand, Left Hand.” It’s a tale of good and evil. Hate: It was with this hand that Cain iced his brother. Love: These five fingers, they go straight to the soul of man. The right hand: the hand of love. The story of life is this: Static. One hand is always fighting the other hand; and the left hand is kicking much ass. I mean, it looks like the right hand, Love, is finished. But, hold on, stop the presses, the right hand is coming back. Yeah, he got the left hand on the ropes, now, that's right. Ooh, it’s the devastating right and Hate is hurt, he’s down. Left-Hand Hate K.O.ed by Love. Top of Second, Hate Batting, Behind 0-2 Bottom of Second, Love Batting, Tied 2-2 Second inning notes: One of the problems you notice immediately with “Play Ball” is that there is no guidance on even the most simple shadings of the game of baseball. For example, if there is a runner on first and the next card displays “Ground Out,” is the “Ground Out” a double play? Similarly, if there is a runner on first and the next card is a “Single,” does the runner on first advance to second or to third? I briefly considered introducing some sort of random-choice device into the game to decide on these matters, but nowhere in the rules of “Play Ball” does it suggest that such alterations be made. Besides, if the playing of this game is in part a tribute to all the many hours I spent as a kid playing made-up games, I should just handle this issue the way I would have handled it then—by nudging every close call toward the team I wanted to win. In my favorite game, backyard roofball, this practice manifested itself on certain long ricochets of the tennis ball off the ridged roof. If the “player” pursuing the drive was a member of the team I wanted to win (generally a collection of gutty, limping has-beens and never-weres who were staging an improbable last-chance drive toward glory) I would run as hard as possible and even dive; if the “player” was on the opposition (generally a conglomerate of chiseled automatons with a collective history of monotonous and featureless league domination) I’d maybe hope the ball would tick off my fingers for a thrilling, game-changing triple. The funny thing is, I probably made as many if not more tough catches when I wasn’t trying than when I was, and anyway I never wanted to push things too far in favor of one imaginary team, knowing that in doing so I’d strip the whole time-consuming pursuit of the illusion of drama, and hence meaning. But for “Play Ball” I decided to keep it simple and make one rule to turn all gray areas black and white. At the risk of sounding trite, here it is: When in doubt, go with Love. Top of Third, Hate Batting, Tied 2-2 Bottom of Third, Love Batting, Behind 2-3 Third inning notes: So Hate takes the lead, despite my rule making Hate into a plodding station-to-station team incapable of scoring from second on a single or from third on a flyout (or, as in the first inning, from avoiding the double play). Hate might win! But I’m already running out of previously profiled 1978 cards, and for some reason this actually makes me sort of hopeful. I’ve been writing about these cards for a year and a half, and the game isn't even official. There’s plenty of Ball left to Play. Anything can happen. And maybe Love will get a hand from Gene Pentz, whose card provided the inspiration for this whole endeavor. Only a few more cards to go until I get to his card, the one card whose outcome I already know, Pentz ready to provide that node of offensive attack that is as vitally important as it is mundane. The walk! As we head to the fourth inning, let us pray for Pentz to plant the seeds of a rally for Love. Top of Fourth, Hate Batting, Ahead 3-2 Bottom of Fourth, Love Batting, Behind 2-4 Top of Fifth, Hate Batting, Behind 4-5 Bottom of Fifth, Love Batting, Ahead 5-4 Top of Sixth, Hate Batting, Behind 4-5 Bottom of Sixth, Love Batting, Tied 5-5 (note: Play will resume upon the next celebration of a 1978 card.) Gene Pentz (flipped)

2008-03-10 16:06

I. In 1974, Gene Pentz did not play. It’s unclear why. During my recent series of posts on Vietnam War veterans who played in the major leagues I came across several cards with a similarly statistics-free line adorned with the message "IN MILITARY SERVICE." I feel as though I’ve seen, on other cards, a message that says "ON DISABLED LIST." So I’m thinking that when Gene Pentz DID NOT PLAY he was neither in the military nor injured. So why didn’t he play? For that matter, why was he listed as being on I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, but I do know that if I had a baseball card, the back of it would be riddled, no matter what statistics it measured, with inexplicable gaps. There have been plenty of seasons of spotty employment, plenty of seasons of fetid isolation, plenty of seasons that slid by in a gray haze, plenty of seasons of numbness, plenty of seasons without play. II. When my brother and I first met him he was a 10-year-old farm boy whose life revolved around baseball and baseball cards (a love that he passed on to us), and as he got older his love of baseball and sports in general fed into a burning desire to become a sportswriter. He was the editor of his high school’s newspaper and a writer on his college’s newspaper and after college got a job on a newspaper in San Diego. By the last time my brother and I saw him, years ago, chatting with him for a few minutes outside the press box during a rain delay at Shea, he had bounded from the San Diego job to a job covering the Orioles to a job as the beat reporter following the Mets for the New York Times. He soon switched over to the Yankees and we haven’t spoken to him since, though I hear his voice practically as much as I hear the voice of anyone I know, given my habit of squandering my finite hours on earth listening to sports talk radio and given the ubiquitous presence on such radio of this baseball-crazy figure from my childhood, Buster Olney. III. What I have decided to do is use all the cards from IV. Since he’d gone off to college Buster had not returned home for the summer, but he came home the summer before I got kicked out of school, and as I remember it he was unsure if he’d ever go back. I never knew why he’d decided to take a year off, but I seem to recall that for whatever reason he was seriously considering, for maybe the first time in his life, that he wasn’t going to become a sportswriter. Taken in the long view, this pause of his is almost comical in light of the eventual resumption of his relentless rise to the pinnacle of the sportswriting world (kind of like the old Saturday Night Live skit in which a key-pounding Stephen King stops typing for a few seconds and calls it "writer’s block"), but at the time Buster really did seem to be wrestling with the question of what to do next. After the summer was over and I'd gone back to boarding school, he got a job in a bank and grew a mustache. He'd never had a mustache before and as far as I know he'd never have a mustache again. Ever since then a mustache will occasionally seem to me as a visible trace of an otherwise invisible thrashing against the void. There’s probably some lesson to be learned in the fact that mustachioed Buster was tortured by the lack of an answer to the question of what to do next while I was happy to reside as long as possible in the fantasy of inconsequentiality that I always create whenever I’m neither here nor there. I have good memories of that summer. We did a lot of haying for his stepfather, then played a lot of basketball if there was daylight left and Strat-O-Matic if there wasn't. I didn't want it to end. But I’m guessing that Buster, if he remembers that time at all, remembers it as something he used every fiber of his considerable will to pull himself free from, as if it was quicksand. Astros, 1978

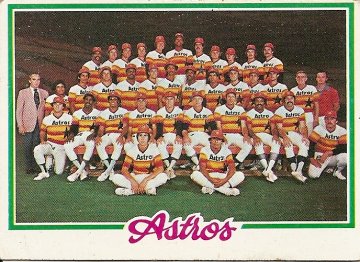

2008-03-07 06:34

I can’t stop thinking about Gene Pentz. At left is the only other card I own, besides the Pentz I displayed a couple days ago, that features the mustachioed obscurity. Can you spot him? I have spent so much time thinking about Gene Pentz that I am tempted to wonder if I have become the biggest fan he's ever had. I would be wrong in that assumption. During Gene Pentz’s brief career there was a Gene Pentz Fan Club. Darren Viola knew the founder and sole member of the Gene Pentz Fan Club. Viola, better known to baseball fans as Repoz (the name he uses in his tireless gathering and hilariously skewed presenting of baseball news at The Baseball Think Factory), was a "friend of a friend" of the fan of Pentz, and wishes when trying to recall him that his "mind wasn’t so alchohazingly damaged from those years." Still, a vivid portrait of Pentz and Fan of Pentz comes through in Viola’s recollections. . . He was one strange kid . . . muy intense and singleminded in his adoration of all things Pentz! Gene Pentz made his major league debut at Shea Stadium. (In 1975, when Pentz was called up to the Detroit Tigers, the Yankees were playing their games in Shea.) I wonder if the future founder of the Gene Pentz Fan Club was one of the 13,410 in attendance on July 29, 1975, when Gene Pentz was brought in to start the sixth inning, the Tigers down 4-2. I’m a romantic, so I’m going to say that he was there, that he was somehow made aware that he was witnessing a player’s first moment in the major leagues, the moment that put Gene Pentz officially in the record books for all time, the moment that would make him, Gene Pentz, immortal. And when Gene Pentz struck out the first man he faced (Chicken Stanley) and went on to pitch three innings of no-hit ball, albeit to no effect (the Tigers were unable to rally), it’s easy to envision a weird kid in the mostly empty stands deciding to follow every step of the brand new major leaguer's journey. It’s easy to envision a weird kid in the mostly empty stands falling in love. Pentz made one more appearance at Shea as a Tiger, giving up four hits, a wild pitch, and two runs in one inning of a 9-6 loss (attendance: 7,240), then appeared twice at Shea as an Astro, once in 1976 and once in 1977. It makes me happy to imagine the founder of the Gene Pentz Fan Club in the stands at these two games. In the first of these games (attendance: 13,303) Pentz recorded an old-fashioned when-men-were-men three-plus-inning save, squelching a rally in the 6th inning and keeping the Mets scoreless the rest of the way. In Pentz’s last appearance at Shea Stadium, he pitched two scoreless innings and picked up one of his eight career major league victories. That game, oddly, was played before 52,784 people, possibly the largest audience ever to witness the artistry of Gene Pentz. I’m not really sure why there were so many people at the game. It was a Saturday game, but a quick glance at other Saturday games at Shea that season shows low attendance figures in line with other Gene Pentz appearances at Shea. Maybe there was a big promotion that day. Or maybe the one-day spike was due to the fact that just three days before the Mets had traded away Tom Seaver. This was the first weekend game since the trade, so perhaps Mets fans flooded the stadium to voice their profound displeasure with management for trading away their beloved star. If fans were ever going to root, root, root for the away team, it would be Mets fans angrily mourning the loss of Tom Seaver. So if this was the case, then maybe when the founder of the Gene Pentz Fan Club rose to his feet to cheer Gene Pentz as Gene Pentz walked off the mound after his second and last inning of scoreless work, his efforts allowing the Astros to tie the game (they would forge ahead in the next half-inning), maybe, just maybe, 52,000 people followed the lead of the founder of the Gene Pentz Fan Club. Maybe for one slim strange beautiful moment everyone was a member of the Gene Pentz Fan Club. Gene Pentz

2008-03-05 09:22

Step One: Select a card. This step may be done intentionally or at random. If you have sorted your cards into rubber-band-bound teams, this may somewhat inhibit your attempt to be random, especially if you have sorted each team by year and also have a general sense of which teams are thick bundles and which are thin. Still, it may be possible to select a card that you did not anticipate selecting, such as the Gene Pentz card shown at left. How could you ever have anticipated selecting Gene Pentz? Step Two: Try and fail to produce brilliant witticisms at the expense of the fellow pictured on the card. This was done time and again by the authors of The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading, and Bubble Gum Book, the equivalent of the Collected Works of Shakespeare for the baseball card writing genre. Those gentlemen could come up with something hilarious to say about Gene Pentz. You are not them. Almost all your sentences veer toward pretension, and by you I mean me, not you, so feel free to disregard this step, or more specifically to disregard the "and fail" part. Step Three: Google Gene Pentz. Find out things like that he threw a lot of wild pitches and walked a lot of guys and once even threw a strike while attempting to intentionally walk a guy. Step Four: Carry around the card in your wallet, go to work, come home, go to work, come home, etc., go out to a nearby bar on Friday, have a few beers, order a cheeseburger, while waiting for a cheeseburger start to go on a rant about this editor guy who showed some interest in a book idea but then stopped returning your politely seldom and unobtrusive email inquiries, build the rant into an unhinged self-pitying screed about the bloodsucking nature of every single editor and agent in the universe and beyond that, fuck it, everyone in the universe, the whole globe one giant vicious knife fight and all you’ve got is a plastic spork, then when the food comes become enraged about how slow the ketchup comes out of the glass bottle and about glass ketchup bottles in general—“the plastic squeeze bottle solved this fucking problem!”—until you are so worked up you feel you are moments away from smashing the ketchup bottle against the wall, then willfully ignore the attempts by your wife to calm you down, instead picking a fight with her, you complete asshole, then eat your stupid cheeseburger and fries in frosty post-fight silence. Step Five: Consider attempting a whole “He looks like Thurman Munson” thing. Abandon it. Step Six: Consider attempting a whole “He kind of looks like my brother’s JV basketball coach, who my brother saw years after high school, both of them driving delivery trucks, neither in the mood for conversation, nothing more passing between them than a couple grunts of delivery truck guy recognition” thing. Abandon it. Step Seven: Go to work, come home, go to work, etc. Step Eight: Go off on a whole pretentious tangent about how great it is to discover the card of a player that, even though these are your cards, you did not know existed. How wide is the world if it includes Gene Pentz! The fact that not only was there a Gene Pentz, but also that he played major league baseball, seems at such a far edge of the spectrum of the possible as to be impossible, so in a way his grizzled mug staring back at you from somewhere inside the chain link cage they put him in to guard the rest of the team from his complete inability to control the path of his pitches is evidence that the impossible, or near impossible, is possible. That kind of thing. Abandon it. Step Nine: Look for some other card to write about. Become discouraged. Step Ten: Why on earth would you want to write about baseball cards? Reggie Smith in . . . The Nagging Question

2008-03-03 09:41

A few weeks ago on this site, during the conversations about the best everyday player of the 1970s (see Pete Rose for the posing of the question and Joe Morgan for the consensus answer), there was some pondering about who was the most underrated player of that decade. Among the players mentioned were Ken Singleton, Bobby Murcer, Ted Simmons, and Reggie Smith. Bobby Grich and Darrell Evans also probably deserve to be part of the discussion, though a significant part of their quietly effective work was done in the 1980s. 1. He was a great player.

2. He is an underrated player.

I wonder if this last part is due in part to the fact that he moved around during his career. Maybe he never quite belonged to any particular fan base, so no one is around to sing his praises. So I'm singing his praises. Whose praises would you like to sing? In other words, the Nagging Question: Who is the most underrated player of the 1970s? Ted Williams

2008-03-01 07:09

Elysium (continued from Carl Morton) Chapter Six My eyes are shut tight and my hands are pressed against my ears, but Richie Hebner’s singing continues to seep in. Shut up, shut up, shut up, I try to say. He stops. I keep my eyes shut. I don’t want to know. Richie Hebner starts thumping a slow rhythm on the ground with what must be the butt of his shovel. He resumes singing, now in a laryngitis rasp that drags behind the slow shovel-thump. What does it matter, a dream of love or a dream of lies The Tom Waits impression makes him cough. The cough turns into a gravelly chuckle. I can’t take it anymore, I try to shout. Like all the other words, these stay trapped inside me. All that comes out is a cornered animal whine, like a trapped cat. Richie Hebner starts rasping the chorus. And we’re all gonna be I open my eyes and lung toward the sound of the singing. I tackle dirt, Richie Hebner gone, his song a crumbling echo in my ears. I gasp from drilling my body into the ground and the ground is wobbling. More than wobbling. Things are always more fragile than you think. The ground is pitching and yawing like a swatted frisbee. I grab at the ground but just slide back and forth with dirt clumps in my fists. Finally I grab something that doesn’t give. The handle of Richie Hebner’s shovel. It’s buried in the dirt. I hold on with both arms and look around. The circular track is gone. I’m at the bottom of a shallow, contoured, circular pit that seems to be plunging and darting through space. Except for the circle of dirt immediately encompassing me the wobbling, yawing disc is the color of lemonade, faintly glowing. It teeters and reels, a glow-in-the dark frisbee, the cheap kind, upside-down and plummeting. The only sound is that of an animal whine, the same sound I made just before lunging at Richie Hebner, but the sound isn’t coming from me. Out along the rim of the disc, where Carl Morton was circling, there’s a small white and orange cat, hunched up and clinging to the edge. She’s making the sound. I realize who the cat is at the same time that I understand I’m the one that caused her current suffering. Things were fine, were peaceful, before I started blundering around the underworld. It’s OK, Wortel, I try to say, but I just add my own whine to the cat’s. She’s looking around, trying to find something to hide under, but there’s nothing, so she huddles up against the lip of the upturned spastic disc. The earth I’m pulled up through is dark and thick, not just with soil and rocks. I can hear Richie Hebner rasping. Hell’s boiling over The earth I’m being pulled up through is clogged with bodies. I’m being dragged up through bodies. It’s too dark to see them and I have to keep shutting my eyes to keep the dirt from flooding my sockets. I can’t breathe. The shovel pierces the surface above me and gray light comes in, illuminating the body closest to the top, a corpse in the uniform of my favorite team. The corpse has no head. I’m so close as I pass that my body and the corpse touch, the corpse flipping from the side that says Red Sox to the side that has the number 9. The last words of Richie Hebner’s song rattle in my ears. . . . just dirt in the ground And I’m standing in the gray light, in the backyard of a house in Racine, Wisconsin. I hold a shovel in my hands, the blade of it touching the freshly dug dirt at my feet. It’s 2003, the year my girlfriend and I left New York City. The year before, contemplating a move, we took a long road trip, traveling from baseball stadium to baseball stadium. We were at the stadium in Pittsburgh when a pregame announcement was made that Ted Williams had died. Some time later the news surfaced that Ted Williams’ head had been removed from his body and was being frozen in hopes that someday a cure for death could be found, at which point he would be thawed out, revived, and reunited with his loved ones. It’s 2003, and I'm back above ground, and a cure for death has still not been found, and so I’m in the backyard of a house in Racine, Wisconsin. I’m standing beside my girlfriend, Abby, who was the one who brought Wortel into the world of human love by dragging her out from under the guest bed every day. Her mother and sister are here too. Earlier that day a neighbor had found Wortel on the side of the street. We went and gathered her in a black garbage bag. Abby’s father is away on business, so I did the digging and the filling in after we laid her down. The shovel's in my hands. We form a circle around the grave. It's 2008. No shovel. No Richie Hebner. Ted Williams still a dead frozen head somewhere in Arizona. I was born on this day exactly forty years ago. Can't fucking believe it. I've got my little life, my routines, my ways of passing the time. I make a living, carve out some time to write, go on long walks, follow baseball, once in a while go out and have a few beers with my wife, occasionally lie awake thinking about the terrifying implications of a notion perhaps best expressed by the Dead song "Box of Rain": "Such a long, long time to be gone, and a short time to be there." When you're dead, there goes everything, and forever. Down you go into the pit, into Sheol. "Enjoy life with the wife whom you love," an old blues singer once said, "all the days of your vain life which he has given you under the sun because that is your portion in life and in your toil at which you toil under the sun. Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with your might; for there is no work or thought or knowledge or wisdom in Sheol, to which you are going." (Ecclesiastes, 9.9-10) Sometimes I think back to 2003, those months when Abby and I stayed with her parents in Racine. We were in between worlds, no longer in New York City and not yet in Chicago. In reality it was a somewhat edgy time, both of us looking for a job, wondering if we could actually pull off a move to a whole new city, but in my memory those months stand as something like an extended train ride, one of those long moments when nothing is of any real consequence, and so time seems suspended, and so death seems far off. I went on runs, circling the streets. I went on drives, making wider circles. Sometimes I went to an amusement center with some golf clubs borrowed from Abby's dad and I bought a bucket of balls and sent them one by one out into a dry field. Once in a while I hit a ball just right, my swing by accident as close to perfection as I'll ever get, a faint echo of the perfection in the baseball swing of The Immortal, Ted Williams, that swing that held nothing extra yet held the whole brief graceful comet flash of life, dawn to dusk, dust to dust, each life one clean motion, one blazing song. |