|

Monthly archives: June 2007

Hank Aaron in . . . The Nagging Question

2007-06-30 06:46

I’m off to the land of honkbal later today, so I won’t be posting for a while, but I wanted to say one last thing before I go: Thank you, Hank Aaron. By the time I get back to the daily boxscores you may no longer hold the record for most career home runs, but to me you always were and always will be the Home Run King. I bought my first baseball cards in 1974, when I was six and you were on the brink of breaking a record that was thought unbreakable. For whatever reason, I seemed to need gods, and I found them in cardboard rectangles, and the cardboard rectangles that held your image always shined the brightest. My family was in a new house that year, in a new town, a new state. My father had not come along. We house-sat for a year, then moved into another house bought for cheap in a foreclosure auction. The room I would share with my brother had been damaged by the evicted former owners, as had all the rooms in the house, the walls riddled with beebee holes and obscene graffiti. I have written about that house a lot, often focusing on the early days, on the feeling that something in the universe was telling me I wasn’t welcome. After those early days I went where I was welcome, into the cardboard rectangles, into the baseball encyclopedia, into library books about baseball, into the game itself, playing for my little league team whenever the long Vermont winter finally relented, playing with my brother whenever he’d agree to, playing by myself with a glove and a tennis ball and the various jagged angles of the exterior of our house. And everywhere I went into that welcoming world, you were there, Hank Aaron, shining down from the pinnacle, majestic and benevolent, the King of the Cardboard Gods. Two days ago my brother’s wife gave birth to their second child, Theo. Nobody could ever love a kid more than my brother loves his daughter, but Ian admits to being excited about the gender of the newest arrival. "It’s not about, ‘Oh, now I can teach him sports . . .’," he said, his tired voice trailing off. "No, I get it. You were a boy." "Right." When my brother was a boy he idolized Hank Aaron even more than I did. On the wall above his bed, a wall that had in our rawest days in the house served as a canvass for a beebee riddled invitation to lewd sex acts, he had a large poster of the moment Hank Aaron became the all-time home run champion. It was a panoramic shot of the moment, showing Al Downing on the mound and Hank Aaron still in the batter’s box, his classic, compact swing in its follow-through, his head craned up to follow the flight of the ball, which was high above the outfield, a tiny white blur haloed by the makers of the poster for emphasis. When my brother was a boy he was not always happy, but he dreamed every night below this holy tableau. Anyway, that’s my answer to today’s Nagging Question. So let me throw it to you: If given the chance, what would you say to Henry Louis Aaron? Bert Blyleven

2007-06-28 09:52

“I know I've got a lock on the Dutch Hall of Fame.” – Bert Blyleven Bert Blyleven was born in Zeist, Holland, but only lived there briefly before his family emigrated to Canada and then California, where he grew up and where his father got his Hall of Fame caliber career started by taking him to see a game pitched by Sandy Koufax. I wonder if Blyleven’s father played baseball in Holland. Apparently, America’s national pastime is not as obscure in Holland as it is in other far-off lands: according to The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball by Jonathan Fraser Light, the Dutch have been playing baseball since a gym teacher brought back knowledge of the game after a trip to the U.S. in 1910, and the Dutch have perennially vied with the Italians for the honor of the top baseball power in Europe. My favorite Dutch player would have to be Win Remmerswaal, a pitcher who lived up to his given name three times for the Red Sox in 1979 and 1980, but, alas, I have no Win Remmerswaal baseball card in my collection, and so I turn to the pride of Zeist, Rik Aalbert Blyleven, to help me celebrate my upcoming belated honeymoon to Holland, now just two days away. Excited about this, I haven’t been able to write much all week, and today is clearly not going to provide a breakthrough on that front. Luckily I can merely pass along some of the deluge of great stuff written about Blyleven’s Hall of Fame candidacy in recent years by directing you to Bert Belongs, which features among many other highlights links to articles by Blyleven’s most eloquent and persistent champion, Rich Lederer (see, for example, “The Hall of Fame Case for Bert Blyleven”). I can’t really supplement any of that commentary except to voice agreement. What do I know? I’m just an aging cipher with a box of old baseball cards. All I can add is that when I got this 1977 Bert Blyleven card I most likely did not get the same immediate thrill I would have gotten had I found a Tom Seaver or Jim Palmer card in the pack. But I’m sure it grew on me. There was the name, first of all, sinuous and even a little hypnotic if repeatedly mumbled several times in the privacy of one’s room—Blyleven, Blyleven, Blyleven. And there were the numbers on the back, excellence partially hidden, camouflaged by the so-so won-loss record, the excellence more rewarding, even joyous, to discover. And last but not least there was the birthplace, more strange syllables to utter—Zeist, Holland, Zeist, Holland, Zeist, Holland—hypnotizing the chewed-gum nowhere day into something strange and wide. Bobby Cox

2007-06-26 07:20

The day Cox earned his big record-tying ejection, I watched Bruce Bochy get tossed from the Fox Saturday game of the week between the Yankees and Giants. What does it say about me that I envied Bochy? I imagined being relieved of the burden of making consequential decisions, going back into the cool clubhouse, popping a beer, seeing if there was a good movie on the clubhouse television. As it turned out, the game Bochy was ejected from went on and on, seven more innings beyond Bochy's 6th inning banishment, so Bochy would have even had time to sneak in a lengthy nap before the team and the press came barging in to wreck his long moment of blissfull purposelessness. Thinking of that blissfull purposelessness (which I'm sure Bruce Bochy had none of, instead maybe kicking a chair or punching a locker and then monitering every second of the rest of the game while perhaps relaying pointed messages to the acting manager via the batboy or some bench-warmer) reminds me of rainy days in the summer of 1986, my second living with my grandfather on Cape Cod. That summer I eventually ended up back at the Shell station where I'd pumped gas the previous year, but for a few weeks before that I worked as a canvasser for Greenpeace. On days when it rained really hard they'd cancel the canvassing. It's been over twenty years and I still can't get over those rainy days. That job--knocking on door after door to cheerfully recite a scripted spiel about the encroaching environmental apocalypse and the need for monetary contributions--made my stomach hurt, plus I was terrible at it. My last day before I quit I left my route after a couple hours of doors slamming in my face and bought a pack of baseball cards from a Cumberland Farms. I was leafing through them when my supervisor pulled up to bring me back to the office. He asked if a kid had given them to me, implying that buying baseball cards was something I was way too old to be doing, especially on company time. He was my age, or maybe a couple years older, a blond college guy who was a big fan of the Zippy the Pinhead comic strip. The next day I found myself praying for a giant rainstorm so I could sit around the house getting stoned in my room and lying on my grandfather's orthopedic bed going up and down by remote control as my grandfather and I watched Match Game and M*A*S*H. But the sky was blue with no hope of rain, not a cloud anywhere. So I just quit. Nate Colbert

2007-06-24 11:06

The best offensive counterpart to Steve Carlton’s famous 1972 season may have occurred in that very same year: Nate Colbert drove in 111 runs for the San Diego Padres, the only 1972 National League team to score fewer runs and win fewer games than Carlton’s Phillies. Colbert’s RBI total accounted for a whopping 23% of the Padres’ total 488 runs. I don’t know if this is the highest percentage in history, but I did check the ratio of RBI to team runs scored for the top single-season RBI producers in baseball history, finding that single-season leader Hack Wilson drove in 19% of his teams runs in 1930; Lou Gehrig 17% in 1931; Hank Greenberg 20% in 1937; and Jimmie Foxx 19% in 1938. Seeing that the top single-season RBI totals were all produced in the hitter’s paradise of the 1930s, I also scanned farther down on the list of RBI leaders for players from relatively low-scoring eras and checked a few deadball era single season RBI champs for their ratios, too. Then I got tired of the whole task and decided to unscientifically cut to the chase and crown Nate Colbert as the greatest single-season RBI producer in the history of the game. I also feel that he had the greatest pair of muttonchops. Anyway, here he is late in his 11-year career, looking a little melancholy, as if he knows there are only two more major league home runs left in his bat. Dwight Evans

2007-06-21 08:19

Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey I spent two summers working at a gas station and living with my grandfather on Cape Cod during the era when Dwight Evans was king. I made my way to Fenway more often during those years than I ever had or ever would, taking a quick busride in from Hyannis to meet up with friends or sometimes just to go to a game by myself. Even if I was on my own, maybe especially when I was on my own, I threw my voice into the chant for Dwight Evans like I was throwing a thin dry stick onto a fire. Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey I was 17, 18, hadn't amounted to much, had an expulsion and a GED diploma in my recent past, had no skills, no girl and absolutely no prospects for a girl, and no vision for the future beyond vague thoughts of some sort of selective nuclear holocaust that would rid the world of everyone but me and the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. Most days I pumped gas and wiped windows with a squeegie and sat behind a register bored out of my skull until it was time to pedal my grandfather's creaky bicycle home. Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey My grandfather kept the fridge stocked with Miller Genuine Draft. He also kept frosted mugs in the freezer. Often there was a Red Sox game on Channel 38. These things--beer in frosted mugs, ample games on TV--had eluded me in my youth in rural Vermont, and suddenly here they were, consolation prizes to numb the general sense that my life was like a game in the hands of an unraveling bullpen. Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey The television was in my grandfather's bedroom, the one he'd shared with my grandmother until she'd died in her sleep five or six years earlier. We watched the games together, my grandfather in his remote-controlled La-Z-Boy and me in my grandfather's remote-controlled bed. The two of us didn't talk much, but sometimes I'd explain something about the game to my grandfather, who though always ready to enthusiastically support something had never been a huge sports fan. Sometimes we wouldn't talk but would just use our respective remote control devices to raise and lower our torsos or raise and lower our legs. My grandfather had trouble breathing, especially in the second of those two years, and in the quiet moments where no body parts were being raised or lowered you could hear the sound of the oxygen machine, which had a clear rubber tube running from its place in the next room up into my grandfather's nostrils. Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey Sometimes the game would devolve into nothing, a slow dissolve into another loss, but then again sometimes, and more and more that second year, the game seemed to build to a point, a crux, a moment when someone on the Red Sox had a chance to step forward and scatter the creeping ubiquitous fog of failure. My memory is full of distortions, is actually nothing but distortions, so I have no idea how many times this actually happened, but when I think of those years I see Dwight Evans slowly striding to the plate with the game on the line, and I see myself lying on my grandfather's orthopedic bed, and I hear myself praying silently but with all my might for Dewey to come through. Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey . . . Dewey And I see Dewey working the count to 3 and 1, the chant getting louder with each pitch until it blooms into a greater wordless roar. And I see Dewey uncoiling and swinging and sending the motherfucking ball onto Lansdowne Street. Frank Tanana

2007-06-19 10:18

(Note: The following is by guest blogger/New York Mammoth Immortal Henry Wiggen, with punctuation freely inserted and spelling greatly improved by Josh Wilker) "Pure Heat" By Henry Wiggen As my grandchildren would surely complain to you for days if they had the chance, I am constantly screeching about the importance of recycling nowadays. So leave me begin by recycling some old words that I saw as fairly crooked when I first read them many years ago: "You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Southpaw." That’s from Mark Twain of course, except with a different title switched in there, my first book instead of Tom Sawyer, and here is what I have said about that starting of Huckleberry Finn previously on page 25 of the book I already mentioned and which is still available at Bison Books in case some money is burning a whole in your pocket: "I told Aaron that was a dirty trick to start a book that you no more opened then the writer was telling you to read another as well. He laughed, though probably I flung the book at him. I was a terrible kid for flinging things at people. I once knocked Holly unconcious with a sour apple. [Note: The Aaron mentioned was not the Immortal Hammering Hank Aaron but Aaron Webster that used to live next to Pop and me. Also Holly was not at that time of the sour apple but is now my long suffering wife as many know though we split up for some time and have only recently reconciled with a human bridge made out of grandchildren.]" Leaving aside the fact that this above quotation is yet even more recycling, as you may have noticed, I am only mentioning these things so as to give you some idea of who I am if you have possibly forgot not only my four books in title The Southpaw, Bang the Drum Slowly, Ticket for a Seamstich, and It Looked Like For Ever but perhaps also my two league MVP awards and many All Star appearances and several heroic World Series exploits plus my 247 career lifetime wins and also a few key saves in my final season before getting drilled in the eyeball with a scorcher back though the box that made me move into a loving embrace of my golden years. Many of these things are matters of some renown I suppose but I see no harm in mentioning them. Especially with the fact that my youngest daughter Hilary’s latest man she drug home could only say with Cheese Doodles on his lips recently "Hey are you not the guy got drilled in the eyeball in Most Awful Sports Injuries Volume Three?" (I am not the only fellow withstanding this treatment. I once saw Joe Theismann who won a Super Bowl as no one seems to recall at a card show and he said the same clucks are also always coming up to him laughing about the joy of a shattered body that needs to be carried off the field in a stretcher. Why this is so enjoyable for the clucks I do not know. Who can figure out clucks?) In fact speaking of clucks I was not at first the least bit interested in participating in this blog, which I do not even really understand the meaning of, blog I mean, though the word sounds like something unhealthy that might show up on a X-Ray that means it’s time to get the bullpen warmed because chances are you are a few pitches away from Hitting the Showers, if you understand my meaning. As I understand it a blog is mostly clucks trying to pretend they are sportswriters like old gigantic hogwash expert now many decades in a grand-piano packing case in the ground, Krazy Kress. Clucks pretending to be Krazy Kress? (Or as I also understand exists Krazy Kresses pretending to be clucks!) When contacted by this fellow Josh Wilker who explained his blog my first response was "I am too busy doing many other things instead such as recycling to save the globe and watching Magnum P.I. while eating my Cheese Doodles which are mine and not for the general consumption of Hilary’s latest man she drug home who wolfs them by the fistful as if he has been starving in a desert." But then he told me about Mark Harris. I did not know my old spelling and punctuation checker had passed away and it made me sad just as it has always made me sad hearing about old teammates and friends. I had not talked to him in a long time, since he added a few commas here and there into my last book It Looked Like For Ever (also available at Bison Books if you are in the mood to throw another reasonable chunk of money around for a book described by the Philadelphia Sunday Bulletin as "a warm, funny, touching book without a trace of sentimentality"). He was a nice fellow, an older guy who loved Carl Hubbell who some compare me to in the anals of the game and he also said he played baseball too though this is something practically everyone with a pulse tells me so who knows how deep the truth goes. Anyway I always liked him and I always thought he believed in my novels that he polished as much as anybody ever done, maybe even more than me sometimes. But what can I say about him really, I asked this fellow who owns this blog you are reading now even though as far as I can tell there’s no money in it. I have not spoken to him in almost 30 years and never once cracked open any of the books he wrote himself and sent me besides checking to see if I was mentioned, which I wasn’t except sometimes on the back cover. "Well," said this Josh Wilker fellow, who to his credit did not ever yell through the phone to check if I was the guy that got drilled in the eyeball in Most Awful Sports Injuries Volume Three but instead asked me about Red Traphagen and Sid Goldman and Sad Sam Yale and others until the answers started collecting into a big pile of gloom. "Well," he said after getting me going about recycling for a while to get away from the gloomy pile of dead teammates. "You can write whatever you want. Anything you write will be a way to honor the memory of Mark Harris because Mark Harris did so much to help you get your story out." "He didn’t do that much," I snapped, forgetting to not speak ill of the dead for a moment, if saying that they didn’t do that much is speaking ill. "I mean, he was a wonderful fellow and loved baseball but I done most of the heavy lifting in those books." I got aholt of myself before saying more but thought: How much does it take to put in a few commas and meanwhile my hand was always a claw after writing one of those books all winter? "Oh, I know, I know," this blog half-cluck/half-want to be Krazy Kress Josh Wilker hurries to say. "I merely meant that he was always there when you wrote your books, like a trusty bullpen catcher throughout your career getting you warm for every 1 of your wins." I thought about that for a while. One thing that was always big to me was my catcher, from Red Traphagen to Bruce Pearson who I roomed with to Piney Woods who I roomed with after Bruce died all the way to Tom Roguski, Coker’s son, who I also roomed with for a few seconds my last season before my starring role in Most Awful Sports Injuries Volume III. "Maybe you can write something about one of my baseball cards," Josh Wilker said in a voice already halfway out the door and defeated. "I rather tell about the necessity of recycling," I said. "Yes, certainly, that would be amazing!" he yelled, back in the door. "The only thing is Mr. Wiggen is it’s got to somehow connect even on a very small level to one of my baseball cards." So he sent me through the computer a photo of the card you see here which Holly had to remove from the email to the computer itself so I could look at if I want to for I do not know how to do such minor things anymore that everyone knows how to do such as even turn on the damn TV to watch Magnum P.I. I looked at it a little, the card, and also looked at what Josh Wilker sent me about the player there. Here is what he sent me: Dear Mr. Wiggen, Well, in answer to his questions I did not have much to do with California or with baseball a-tall after retiring. It wasn’t easy walking away but when I finally did it was like a door shut and I tossed away the key. I still watched a game from time to time but I cannot recall ever seeing this fellow Frank Tanana throwing either heat or slop. I do recognize something of course from the photo itself here and it is the look on Frank Tanana’s face. That is the look of someone like I used to be and maybe still am though now it means I am a old fool. That look is pure and unshakeable confidence. He is of course just standing there not even on a mound when the photo is being took but even there he is got his hands up and ready for his motion and his fingers on the ball and that is waking the feeling of pitching, of being ready to pitch. And when that feeling awakes in the body of a fellow who can reach back for the smoke and the smoke is always there then there is not a better feeling in the world for you cannot be beat. That is what I see in this card, a young man like I once was a thousand decades ago before such things as hips started crumbling who believed from head to toe he could not be beat. I will end by recycling one more thing and pleading that you all recycle too for the world is no longer young with a blazing fastball to get out of every jam. No we are all one big old junkballer who better learn to think things through every step of the way and be extra careful at all times or we are all going to get shelled and hit the showers for good. This following is from my book The Southpaw (which the New York Times called "a distinguished and unusual book") because it is a part I think of when I think of this young Frank Tanana and also of myself and also of my old trusty bullpen catcher of many years Mark Harris, may he rest in peace. It is from page 147 and spring training before my first full year in the majors and if I do say so myself it is not half bad, though it makes me feel a little sad now to read it: I guess I was really in the best shape of my life. I could of shouted and sung, for I felt so good. Did you ever feel that way? Did you ever look down at yourself, and you was all brown wherever your skin was out in the sun, and you was all loose in every bone and every joint of your body, and there was not a muscle that ached, and you felt like if there was a mountain that needed moving you could up and move it, or you could of swam an ocean, or held your breath an hour if you liked, or you could run 2 miles and finish in a sprint? And your hands! They fairly itched to hold a baseball, and there was not a thing you could not do once you had that ball. You could fire it like a cannon and split a hair at 300 feet, and you could make it dance and hop, and the batter could no more hit your stuff then make the sun stand still.

Sparky Lyle in . . . The Nagging Question

2007-06-15 14:54

Cheers for Mark Harris, Part 2 My favorite baseball book is The Southpaw, but it wasn’t always that way. For a while there, before I knew of Henry Wiggen, the tale of a different lefty topped the list. And I still owe a big debt to him. Sparky Lyle got me writing. His diary-style recounting of the tumultuous 1978 season, The Bronx Zoo (written with the help of Peter Golenbock), came out in 1979 when I was 11. I bought it that summer, when my brother and I were in New York City for our annual visit to see our dad. The cover featured a picture of a baseball festooned with a walrus mustache. The mustache bulged up above the otherwise flat surface of the cover, like the raised letters on the front of a Harlequin Romance. I practically went into cardiac arrest from laughing while reading the book on the busride home. My brother and I had always seemed to find a way to laugh our asses off on that 8-hour ride. In earlier years we’d done it by filling in all the blank spaces in Mad Libs with swear words, or coming up with obscenity-laced versions of common acronyms such as FBI and CIA (this latter riff beginning with the two of us inventing “blue” versions for the UFP acronym on my brother’s official United Federation of Planets Star Trek T-shirt). I don’t remember anything particularly funny from the homeward busrides in the years after the Bronx Zoo hilarity, however, which suggests that Lyle’s descriptions of clubhouse pranks and dugout fueds provided our last Greyhound hurrah. By the summer of 1979 my brother had become a teenager, while I was still a kid, the two-year gap between us never wider, and so by then in most settings he reacted to my pestering demands for his attention by, first, totally ignoring me, then if that didn’t work fixing me with a brief glowering stare, and finally if I still kept at it unleashing a spring-loaded backhand punch to my upper arm. But I guess the regular rules were—up to and including that summer but not beyond it—suspended for our busride home from seeing our father. In that moment of suspension between parents it was the two of us against the world, laughing. And in that last laughing busride we had Lyle’s book open between us, painting a graphic picture of grown men acting like children: bickering, playing baseball, cursing, playing baseball, getting in fistfights, playing baseball, and, in the most memorable running gag, perpetrated repeatedly by the book’s narrator upon a string of teammates, sitting bare-assed and ruinously on birthday cakes. All this must have been reassuring to me. If they haven’t grown up, maybe I don’t have to grow up, I thought. Baseball can go on, laughing my ass off can go on, feeling like I’m part of a team can go on. All these things had buoyed my childhood, and though I didn’t consciously note their imminent departure from my life, the fact is they were all on the brink of diminishing, and on some level I must have sensed this. So I seized on Lyle’s book, which is another way of saying I loved it. And when the following year’s little league season came around, my final little league season, I decided to emulate Sparky Lyle. My father had recently given me a diary and had implored me to write something in it every day. The cover of the diary was denim. It had gnomes on it. In fact, it was called a Gnome Gnotebook. It took all my strength not to beat my own ass for owning it. But the evening after my team's first little league practice of the year I ignored the gnomes and began to write, hoping that my increasingly mundane life would instantly burst into side-splitting hijinx. A few years later, during my college years and in a tantrum of frustration at still not being able get down on the page anything close to resembling what was inside me, I tossed all my writing notebooks (including the Gnotebook) into a dumpster. But I still remember the sentence that started my lifelong attempt to write down my life. I was trying to be sardonic and weathered, a crusty self-deprecating veteran. I guess I was probably trying to sound like Sparky Lyle. And I was trying to tell the truth. “I couldn’t lay my glove on anything today, much less my bat,” I wrote. II. III. What is your favorite baseball book? Champ Summers

2007-06-14 08:35

I. Throughout my life I’ve read The Southpaw several times, Bang the Drum Slowly several times (though not quite as often as The Southpaw), and also Harris’s non-baseball novel Speed, which I liked a lot. Additionally, I sort of read It Looked Like For Ever, the fourth and final Harris novel featuring immortal New York Mammoth hurler Henry Wiggen as narrator, but I’m pretty sure I ended up skimming the last part of it. It was a gift for a friend, but before I gave it to him I had to check it out for myself, and was mostly disappointed by it, probably in part because I was sure a book about Henry Wiggen struggling through his final season could not possibly fail to be immensely enjoyable. Unfortunately, there was hardly any baseball in it at all (or “a-tall,” as Wiggen would say), maybe none, and maybe because of that it amounted to a long and demoralizingly sour death rattle of Wiggen’s formerly ebullient, blistering, hilarious voice. But I may be remembering it unfairly and am planning to give it another try after I first read some of Diamond, a collection of Harris’s baseball writings (which includes among nonfiction pieces an excerpt from Bang the Drum Slowly—all the library copies of the novel were checked out, which was my biggest library-based disappointment since discovering, years ago, in a severe late-20s puberty relapse, that all the pictures in a nearby college library’s back copies of 1970s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issues had been ripped out by some other nostalgic pervert—and the entire screenplay based on that novel, written by Harris) and also after I read Ticket for a Seamstitch, the one Henry Wiggen novel I’ve yet to crack, perhaps because I’m under the impression that most of its fairly slim contents are taken up by a story in which the young eccentric catcher Piney Woods (clubhouse singer of the sad song that gave the previous novel its title), and not Wiggen himself, takes center stage. But I’m ready to devour it all, good and bad, and in a way maybe it’s fitting that my full read of Bang the Drum Slowly will have to come last, instead of second, as I first planned it (wanting initially to read the entire Wiggen chronicles chronologically). Now I’m assured that I’ll end my latest (but with luck not last) foray into the world of Henry Wiggen on a note of brilliance. And it’s fitting that I’ll be able to end my project on an elegiac note, too, Bang the Drum Slowly one of the saddest and most moving novels I have ever read, baseball or otherwise (and I have been reading novels pretty much constantly for two and a half decades, a habit that began in large part with my first reading of The Southpaw). I've cried whenever I’ve read Bang the Drum Slowly, and I’ll probably cry again, except this time I won’t be crying solely for Bruce Pearson but for the man who created not only Bruce Pearson but also Henry Wiggen and Red Traphagen, knarf retrop and Tegwar, and Sam Yale and Sid Yule, to name just a few of the sacred and profane odds and ends and endless beginnings in the pungent and thriving universe of the New York Mammoths. In other words, as some of you probably already know, the greatest of all baseball novelists has died. II. Harris was aware of his debt to Twain, and later became aware of the similar influence of the Twain literary descendent, Ring Lardner, who first brought the American vernacular yarn onto the baseball diamond in 1916 with You Know Me Al. On the other hand, the Alger influence, which had thoroughly permeated baseball fiction by the time Harris began to pen The Southpaw in the early 1950s, was not so clear to Harris at first. He later came to see that his hero, Henry Wiggen, similar to the heroes of the standard stories of baseball triumph, “does succeed, does grow rich, does preserve his moral virtue.” But at the time he was writing the book, he saw The Southpaw as diametrically opposed to the hackneyed conventions of the Algeresque baseball tale. His critique of the conventional “rags to riches” story of uncomplicated good-over-evil victory becomes abundantly clear near the end of The Southpaw, when Henry Wiggen goes to see a baseball film with his slow-witted roommate Bruce Pearson: …even Bruce could see [the movie, entitled “The Puddinhead Albright Story”] for the usual slop that it was where nobody sweats and nobody swears and every game is crucial and stands are always packed and the clubhouse always neat as a pin and the women always beautiful and the manager always tough on the outside with a tender heart of gold beneath and everybody either hits the first pitch or fans on 3. Nobody ever hits a foul ball in these movies. I see practically every 1 that comes along and keep watching for that 1 foul ball but have yet to see it. Wiggen would have seen eye to eye with another fictional early 1950s New York-based malcontent, Holden Caulfield. The hero of The Catcher in the Rye (which as a child I figured was a baseball book because of the fielding position named in the title) like Wiggen hated the unrealistic fantasies of Hollywood. Wiggen and Caulfield, whose sardonic, plain-spoken voices sometimes sound similar even though the former is rising up in the world while the latter is plummeting downward, both loathed all manner of “phonies” in general, and each of their coming of ages can be seen as an increasingly desperate quest to escape the suffocating myth, cultivated by phonies everywhere, that we all get to live happily ever after. Henry Wiggen, like Holden Caulfield, wanted to break through the bullshit to something real. III. Because of that some part of me relished the less than stellar statistics on the back of his baseball card. I assumed because of his name that he was a highly touted “Next Mickey Mantle” (a la Clint Hurdle) who had been rushed to the big leagues after spending his high school years in some golden uncomplicated town single-handedly winning state championships and fornicating with the cream of the cheerleading crop, so I enjoyed his apparent journeyman status as some kind of cosmic comeuppance. In actuality, after high school Summers tried to play college basketball but wasn’t really cutting it and ended up getting shot at by the Viet Cong for a few years instead. After getting out of the Army, Summers got noticed by a scout while he was playing in a softball league. He was 25 years old when he was signed, 28 when he made the big leagues. By the time of this 1978 card he was a 32-year-old veteran who had played, sparingly, for three teams in four years, getting traded first for Jim Todd and then for Dave Schneck. Needless to say, heroes in rags-to-riches fantasies don’t go around getting traded for Dave Schneck. IV. Henry’s changing relationship to iconic images such as the picture of Sam Yale shows up during the climax of the novel, when the southpaw is laboring through the ninth inning of his final regular season start of the year, a game that his team needs to win. Mark Harris could have brought anybody to the plate to face Henry Wiggen, so it’s telling that he introduces a previously unmentioned character to battle his protagonist: Bob Boyne hit for Fred Nance, a man of near 40 that I bought bubble gum as a kid with a card in every chunk and once had a card for Boyne, his picture and his history. Henry Wiggen notes this information calmly, dispassionately, just as he goes on to note Boyne’s strengths as a hitter. His opponent is no longer a hero on a bubble gum card, just a man, like him, nothing more, nothing less. With that in mind, I doubt Henry Wiggen took much pleasure in seeing his own image on a bubble gum card, as he likely would have at some point during the following season. He’s done with reveling in his own rags to riches fantasy, seeing the emptiness of it, the essential phoniness. For others of us the fall from innocence is never so complete. Our childhood wishes cling to us even in the face of years of disillusionment. We still dream of being the child who dreams: One day I’ll become the object of wonder. Apparently, even some of the men who live out the mundane, Schneck-laced reality beneath the fables of awe are loath to give up on their innocent dreams. Writer Joe Goddard, working on a piece entitled “What’s Up With Champ Summers?”, asked his subject to name his best moment as a major leaguer. “The first time I saw my face on a bubble-gum card,” Champ Summers replied. Dennis Blair

2007-06-12 10:19

What if I were to tell you that I have been haunted by Dennis Blair for most of my life? I imagine your first reaction might be to ask "Who is Dennis Blair?" Well, in a certain sense Dennis Blair was a tall, rail-thin pitcher who won 11 major league games at the age of 20, then lost 15 major league games at the age of 21, then appeared in only 5 major league games at the age of 22, then did not surface again in the major leagues until age 26, when he concluded his major league career by going 0 and 1 with a 6.43 ERA for Oblivion’s Vestibule, otherwise known as the 1980 San Diego Padres. That version of Dennis Blair and the version of Dennis Blair that only I know about intersect in this 1975 baseball card. On the back of the card are the details of his career to date, including his height (6’5"), his weight (185), his rapid 2½-year rise through the minors, which climaxed in a brilliant 1974 half-season at Memphis in which he went 5 and 0 with a 1.84 ERA and earned his mid-season callup to the Expos. The line below his Memphis line plainly sets out his promising rookie season, and the text below the statistics further fills in his story: Called up to the Expos during 1974, Dennis entered the starting rotation and hurled 4 Complete Games with a Shutout. He’s possessed with fine control. The construction of that last sentence intrigues me. I would think the more common vernacular, at least currently, would have that sentence being uttered more succinctly and in an active rather than passive voice, as follows: "He possesses fine control." But maybe the Topps scribe knew what he or she was doing when discussing the concept of Dennis Blair’s control as if that control was not something he possessed but rather something which took possession of him, like a spirit of some sort, and in turn could just as easily leave Dennis Blair, which in fact it seems to have done: the following year he was not possessed with fine control, surrendering 106 walks in 163 innings, and the year after that it got even worse as he walked 11 guys in 15 and 2/3 innings. Perhaps he spent the next few years before his final go-round with the Padres arduously venturing to various remotely situated shamans and medicine men around the globe in hopes that they could help him once again become possessed with fine control. I picture his skinny frame wasting away even more than it already had as he suffered the intense heat of sweatlodges and fasted in skeleton-littered deserts and licked hallucinogenic toads, all in hopes that he could once again coax the illusive Spirit of Fine Control out from the shadowlands beyond the sky. It’s possible that he was successful in his quest, though it seems to have exacted a toll that nullified any benefits of his fairly admirable final season tally of 3 walks in 14 innings. Perhaps he contracted a rare tropical disease. Perhaps he injured himself embracing a cactus he thought was the Navajo sun god Johona’ai. Perhaps he became possessed not only with the Spirit of Fine Control but also the Spirit of Surrendering Tape Measure Home Runs. I don’t know. I just know that from time to time in my life a thin seam in the world seems to open. I can’t actually see it, not exactly, but I can feel it. This "seeing feeling" of the seam opening up in the world comes to me in the dark, mostly, late at night, the world gone quiet. It may be more accurate to say that nothing is visible in that seam, but nothing is just a word, too, a collection of symbols to stand in the place of something that is unsayable. So let me instead say that the seam is just tall and thin enough to allow a brief and unsettling glimpse of Dennis Blair. To be more accurate still, it is not a glimpse of Dennis Blair that I get but a glimpse of where Dennis Blair has just been. I see him as you might see the visual echo of a bright light on the inside of your eyelid after looking straight into the light. Then the visual echo fades and the seam closes up again, and I’m left once again to this world, this convincing illusion. It has been this way for a long time. I can’t place the exact time when I first caught a glimpse of the seam, but if I had to guess I’d say it occurred during the years directly following the year this card came out. I got the card in 1975, when I was seven, and though I can’t remember my thoughts upon first looking at it I can guess that I may have been impressed by the status of Dennis Blair as a promising rookie. Here is a guy who will be around for a long time. Then when he didn’t show up in the baseball card sets of subsequent years my growing sense from many directions in my life that nothing lasts forever may have begun to coalesce around the ghost of the 1975 image of Dennis Blair. Tall, thin, sepulchral, vanishing. Even his uniform is of a team that no longer exists. Nolan Ryan

2007-06-11 08:31

Life is not like a box of chocolates. When I’m left alone with a box of chocolates I puncture a few with my thumb to see if they have anything inside them that would make me gag, such as coconut or the lurid red guts of sugar-lacquered fruit. You can’t really do this with life. You’ve pretty much got to taste everything that comes your way and then either swallow it down past the rising bile or go hungry. But maybe life is like a pack of baseball cards, specifically a pack of baseball cards purchased with September looming, the sweet myth that summer will last forever disintegrating. You have been buying cards for months already, the thrill of seeing the year’s new card style long gone. You’re sure to get mostly doubles in the pack, guys you've already picked up in previous packs, one monotonously recognizable personage after another posing like zombies in infielder crouches or with bats outstretched. Disappointment, monotony, the taste in your mouth a quick burst of sugary gum then back to what it was before you opened the pack, the gum already a hard rubber pebble. Ah, life: Each new day a low-quality xerox of its predecessor. But if I had one message to impart in all these many cardboard prayers it would be that there’s always the chance in the late-summer baseball card pack called life that you might find a card like the one pictured here mixed in with all the doubles. I was 12 when I found this electrifying 1980 card among all the repeating Thad Bosleys and Steve Muras. At that time there was no bigger star in baseball than Nolan Ryan. He had already begun rewriting the record books, but more than that he seemed to have superpowers. Other pitchers such as Jim Palmer and Tom Seaver seemed to have more success winning ballgames and Cy Young awards, but only Nolan Ryan had the power to crack open the hard lid of the late summer sky and let a little of the dreamworld come leaking in. He threw the ball fast, faster than anyone ever had, faster than anyone ever would. A 12-year-old kid who had played his final year of little league and gone through his first demoralizing year of junior high could walk home from the store where he bought this card and hold this card and feel like he was holding a little piece of lightning from another world. Lou Piniella

2007-06-07 11:19

Tantrum 1: I was a real tantrum-thrower as a kid. My most public tantrum came at the end of a little league game. We were playing the Twins, one of the two or three teams in the league we had a chance to beat, and were leading by three runs in the bottom of the last inning. They loaded the bases for their best hitter, a short, stocky kid named Tom Soule. My mom was watching the game from the metal bleachers behind our dugout. I was playing third base. Tom Soule swung and sent the ball sailing. “It was such a nice moment watching little Tommy Soule bounce around the bases with a big smile on his face,” my mom told me afterward. “Then I look up and see you. Kicking your glove across the field. Swearing. Crying. It was awful.” My punishment was going to be that I’d have to miss my next game, but no doubt because punishments were pretty foreign to my hippie-influenced family this never came to pass. I think Mom just had me stack firewood instead, which I would have had to do anyway. Usually when I stacked firewood there was a Red Sox game on the radio, so it was actually a decent way to pass the time. Tantrum 2: My most elaborate tantrum also was little-league related. In Vermont, winter never ends. This is how it feels when you’re an 11-year-old kid getting angrier and angrier as each new April snowstorm cancels another stab by your team to have their first practice. Finally when yet another sleet- and snowstorm cancelled practice I decided that the only thing there was to do was go try to get in a fistfight with the weather. I put on a thin windbreaker over a T-shirt—probably what I’d been planning to wear to practice—and set out into the howling storm. Having already watched too much television in my life, I imagined with some intensity the following scene centering on my departure: as I was about to exit the house some parental figure would ask me where I was going. “Out,” I planned to say, toughly, before opening the door and slamming it behind me. But nobody asked me anything, or even noticed I was about to go Ahab it up a little against the northern New England squall, so I just left. I ended up walking 8 miles in my sneakers through sleet and snow, all the way up the winding dirt road from East Randolph to Randolph Center. My friend Glenn lived in Randolph Center, so I went there and called home. My grandfather, who happened to be visiting, came and picked me up, unsure what to make of me. “Damnedest thing I’ve ever seen,” he murmured. By then my anger had kind of receded behind the encroaching hypothermia. Tantrum 3: Just yesterday, in my cubicle, I was having great difficulty figuring out how to change the color of the text in these tiny text boxes we use to signal edits in a PDF document. This is the kind of thing that really gets to me these days, the conundrums that make me feel like I’m a stranger in a strange land, and that it’s only going to get worse as I get older and less able to adapt to the constant technological “upgrades” all around me. I hate upgrades. I loathe them. Soon death itself will be referred to as an upgrade, for isn’t an upgrade a wiping away of one world in favor of a whole new world with no memory of the old? Anyway, that’s not really what gets me wound up in those moments. It’s the feeling of helplessness and stupidity. So instead of calmly trying to figure out a solution to a problem, I throw a quiet masochistic tantrum. So yesterday if you happened to be in my sector of the corporate headquarters where my name hangs on a cubicle you would have seen a 39-year-old man pulling his hair and punching himself in the head. Well, you probably wouldn’t have seen this, because whenever I am about to deliver blows to my head I take a quick look to see that no one is within witnessing range of my cubicle. But maybe there are hidden security cameras. Tim Jones

2007-06-05 13:24

Why have I spent the last several months delving on a nearly daily basis and with alarming thoroughness into the shadow cast on my life by the baseball cards I collected in the mid- to late-1970s? Here are some theories: 1. I am afraid of dying. Once every couple weeks I wake up in the middle of the night and all the distractions are gone, leaving a clean view at our raw deal. How could this all end? Everyone’s in the same boat on this one, but of course not everyone seems as crippled by the news. Cardboard Gods is my ultimately futile attempt to crawl into a fetid, familiar bunker and hide from the inevitable. 2. I am afraid of living. Living leads to dying. Better to hold fast to the rectangular shards of the past than venture out into the unknown. 3. I am seeking the wonder of childhood. "We all dream of being a child again, even the worst of us. Perhaps the worst most of all." – Don Jose, The Wild Bunch 4. I am trying to invent a religion that will work for me. Several years ago I hitchhiked from Vermont to Boston to see a Red Sox game. I was 19 or so. A guy picked me up on the on-ramp to the interstate in Montpelier. He had black, fake-looking hair, a black, fake-looking mustache, and skin like raw tofu. "The Red Sox, huh? Rico Pepper-celli," he said, mispronouncing the name of the Red Sox infielder who had retired years earlier. "Right," I said. Then he abruptly changed the subject. "I was like you," he began. "Messed up on drugs. Aimless. Drifting. Then one day I got down on my knees and gave myself over to Jesus Christ." As we drove on the guy talked a lot about death and heaven, but his heaven seemed a brightly-lit eternal meat locker, terrifying in its lifelessness. I need a different kind of heaven, different gods. Many gods. Gods both admirable and faulty, heroic and obscure. Which brings us to . . . 5. Tim Jones. Tim Jones reached the major leagues in September 1977. His first two appearances were in relief in games the Pirates were losing badly, and his third was as the starter in the first game of a doubleheader on the final day of the season. He won that game, pitching 7 shutout innings, and in all pitched 10 major league innings without being scored on. He was traded in March 1978 to the Montreal Expos for Will McEnany and never appeared in another major league game, his lifetime record unmarred, 1 win, 0 losses, 0.00 ERA. This card represents Tim Jones’ sole appearance on a baseball card. The three players he shares his lone card with, on the other hand, all went on to have several individual cards produced in their likeness, Mickey Mahler lasting a few years as a largely ineffective southpaw starter, Larry Andersen enduring as a useful reliever for 17 seasons, long enough to stumble into undeserved infamy as the less weighty entity in one of the more lopsided trades in baseball history (in which he was exchanged for a minor league first baseman named Jeff Bagwell), and Jack Morris, whose all-star career and post-season mastery have prompted more than a few fans and experts to call for his induction into the baseball Hall of Fame. But for Tim Jones, this is it. His one and only moment. All of us are Tim Jones, in a way. All of human history is but a tiny blip in the life of the universe, and each individual life within that history is an even smaller blip. In that light, even Shakespeare's collected works don't amount to much more than what Tim Jones appears here to be thinking: Wait, what? Joe Morgan

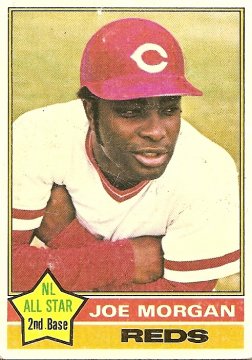

2007-06-04 13:23

I've got nothing today. I feel like I'm made out of wet cement and potato chip farts. Friggin' Monday. I don't work at my job on Monday, so it's the day when I'm supposed to take the world by storm, you know, live my dream life, write shattering tales pulsing with the rhythms of undying prose, etc., etc. But I've just been stopping and starting all day today, trying and failing to fight through a painful ache that seizes me whenever I try to compose letters of inquiry to literary agents who don't know me from a begger on the subway. So just to keep from going nuts I'm going to take a short break from composing tedious, desperate explanations of how my festering unpublished novel is a sellable undiscovered gem. I'm going to look at my baseball cards. I'm going to look at my baseball encyclopedia. I'm going to enwomb my 39-year-old self for a little while in these activities that have soothed me and temporarily walled me from my troubles for most of my conscious life. More specifically, I'm going to ask this question: Who's better, Joe Morgan or Rogers Hornsby? The discussion attached to the previous posting here on Cardboard Gods came to the collective decision that the man shown here burying his hands in his armpits is superior to his rival for the second-base spot on the all-time team. This decision is in line with Bill James' thinking on the matter, as he related in his Historical Abstract: If you count his walks and steals, Morgan accounted for 6,516 career bases, leading to 1,650 runs scored. Hornsby accounted for 5,885 bases, leading to 1,579 runs scored. Hornsby played in a league where teams scored 4.43 runs per game; Morgan, an average of 4.11. Hornsby was an average fielder and a jackass; Morgan was a good glove and a team leader. (pp. 360-361) The one factor left out of the above group of numbers is games played. Morgan played in 2649 games to Hornsby's 2259, and so produced fewer bases and runs per game than Hornsby. Hornsby's era saw more scoring in general, but unless I'm doing the math wrong (always a possibility), the ratio of his runs per game over Morgan's runs per game is greater than the ratio of his era's average runs per game over Morgan's era's runs per game. Because of longer seasonal schedules and a slightly longer career, Morgan was able to compile more bases and runs than Hornsby, but I disagree with the claim that he was as potent an offensive force as Rogers Hornsby. The clincher to this argument, to me, comes from a look at how each player stacked up against other players of his era. Was Morgan the greatest offensive force of his day? For a couple years he probably was, and that's pretty amazing for a Gold Glove middle infielder. He led the National League in on base percentage four times, in slugging percentage once, and in OPS (on base percentage plus slugging percentage) twice. Not too shabby. But now hear this: Rogers Hornsby led his league in OPS eleven times. Eleven! I just took a look at the records of the top names on the career OPS leader board at baseball-reference.com, and it seems, according to my unscientific perusal, that in the history of the game only Babe Ruth led his league in that most telling offensive statistic more times than Rogers Hornsby. Now, I guess Rogers Hornsby was a pretty bad fielder and a dismal teammate. Also, he and all pre-Jackie Robinson major leaguers surely benefitted from competing in a segregated league. With those things in mind, I really can't say with any certainty that Rogers Hornsby was better than Joe Morgan. But isn't it tempting to imagine an all-time best lineup that includes a player at second base who is by a certain key measurement the closest anyone has ever come to being Babe Ruth? Rich Gossage in . . . The Nagging Question

2007-06-01 08:53

It’s my way of hiding from the world, I guess, and as ways of hiding from the world go I guess it’s not too bad. Still, one of these days The Nagging Question should be “Why am I hiding from the world?” But today’s not that day, probably because I’d rather hide from the world and burrow down deep into that rich cluster of meaningless distinctions and impossible scenarios I call my all-time team. It changes all the time; in fact just today I reduced the pitching staff from ten men to nine and decided on a new backup catcher after years of going with a personal favorite, Mickey Cochrane, for the job. But here’s how I see it today: Most common starting lineup: Pitchers: I could go on at length about each and every choice on here (and actually I’m hoping the chance to do so will arise in the comments portion of this post), but for right now I’ll just note three recent alterations: 1. As mentioned above, I waved the man who Mickey Mantle was named after in favor of Buck Ewing. I decided I needed a representative from baseball before the 20th Century. It doesn’t seem likely that from all the players who took the field before 1900 there wasn’t a single one who deserves to be part of my all-time roster. Ewing was generally regarded as the best all-around player of that era, a .300 hitter with good speed, dominant defensive skills, and an unsurpassed knowledge of the game. 2. I cut the pitching staff down to nine. This allowed me to cut Roger Clemens, but that’s not why I did it. First, I really, really wanted to add another hitter. Second, the starters I’ve got are going to log a ton of innings, and if for some reason I hit a tough stretch in the schedule where someone is needed to eat up innings, I’ve got the tireless knuckleballer, Hoyt Wilhelm, and beyond that I’ve already got Martin Dihigo, who was a phenomenal pitcher, as one of my two utilitymen. If you haven’t heard of Dihigo, he was a Negro League star whose versatility as a fielder could have made Bert Campaneris and Tony Phillips seem like Greg Luzinski, who hit and played the outfield like Roberto Clemente, and who performed so well on the mound that he was inducted into the Hall of Fame as a pitcher (Bill James, on the other hand, ranks him as the best rightfielder in Negro League history). 3. I dropped Dennis Eckersley and added the man pictured at the top of the page in his pre-goatee days. Eckersley was pretty great for a while, but I started thinking about roles on the staff, and I think the 9th inning has to belong to Rivera, whose post-season success (save for a couple beautiful moments in ’04) earns him the closer role. So who’s going to be the right-handed set-up guy, able to storm into a shaky situation and then go for two or three innings? I’d rather have a reliever from the days of the three-inning save than the king of the one-inning relievers, Eck. Plus, I don't think any pitcher ever scared me more than the Goose. But anyway, on to The Nagging Question: Who makes up your all-time 25-man roster? |