|

Monthly archives: October 2008

Carlton Fisk

2008-10-31 06:44

Last week, during The Griddle’s coverage of the weather-enlivened World Series, Bob Timmermann noted the tradition, which resurrects itself whenever it gets a little cold or rainy during the Fall Classic, of sportswriters calling for baseball to ape pro football and move the World Series to a neutral site. Bob pointed out that these articles have been appearing for some time: "One notable article was by longtime AP writer Will Grimsley who, stuck in the cold and rain for two days during one World Series, wondered why the Series couldn’t be moved to the Astrodome. Grimsley’s article was written the day before Game 6 of the 1975 World Series." This morning I heard someone on ESPN radio who had been at that famous game, Peter Gammons, adding his highly influential voice to those calling for a movement toward a neutral-site World Series. He said that people ask him (I suppose because he’s from New England) what he would say to Red Sox fans if this idea was put into action. He said he’d tell them that Red Sox fans haven’t celebrated a World Series victory in their own park since 1918. I was jogging when I heard him say this. I started running faster. As soon as I got back to my apartment, I took a book off the shelf that included some words I memorized a few years ago, as others might memorize a poem by Keats or a Shakespeare soliloquy. I had to read those words again. They are from October 22, 1975. And all of a sudden the ball was there, like the Mystic River Bridge, suspended out in the black of the morning. Young Peter Gammons wrote those words, among the best ever written about the game of baseball. He was able by some rare lightning bolt of grace to infuse his clear, charged report of the game’s heroics with a deep and powerful sense of place. The pull of that moment, which will last as long as baseball lasts, has everything to do with the fact that it occurred on a cold New England morning with the long dark winter looming. Fisk's homer occurred, like Joe Carter's homer, like Kirk Gibson's homer, like Bill Mazeroski's homer, like Bobby Thomson's homer, at home. "The writer operates at a peculiar crossroads," Flannery O'Connor once wrote, "where time and place and eternity somehow meet. His problem is to find that location.” Young Peter Gammons found that crossroads, that place, as well as anyone ever has. Old Peter Gammons seems to want there to be no such thing as place. In the radio interview, after pointing out that Red Sox fans haven’t celebrated a World Series victory in their own park since 1918 (as if the only thing worthy of celebrating or remembering is the winner of the World Series), Gammons said he’d tell Red Sox fans that the Patriots didn’t win their Super Bowls in Foxboro. He’s right. But where did they win them? Granted, I’m not a big football fan, but I happily watched the Patriots win their Super Bowls, and I couldn’t possibly tell you where those wins occurred. With all due respect to the cities in which they did occur, to me they occurred nowhere. No place. On the other hand, even though my knowledge of football history is spotty, I can tell you where the Patriots' "tuck rule" victory in the snow over the Raiders occurred, and where the Ice Bowl occurred, and where that old rainy championship game in the 1930s occurred in which the winning team went out at halftime and bought sneakers to contend with the muddy field. Without place: no memory. Without memory: what? It breaks my heart that Peter Gammons, author of my favorite paragraphs ever written about my favorite sport, seems to have lost not only his memory but his awareness of the singular, irreplaceable power of place. Ryan Howard

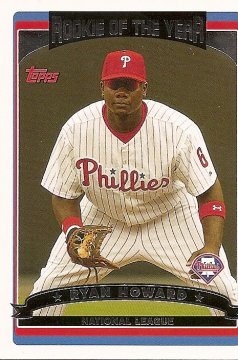

2008-10-30 05:54

The most common form of communal victory celebration in baseball these days is the roiling many-bodied bounce, in which several triumphant players converge and make loud happy noises while hugging and jumping up and down, everyone remaining vertical. These happen near the pitcher’s mound after the last out has been recorded or at home plate to greet the scorer of the winning run or near first base to swarm the author of the game-winning hit or sometimes in two places at once until the two many-bodied bounces converge into one big many-bodied bounce that seems, at least for a little while, capable of lasting forever, of perhaps even morphing into a new kind of everyday being with its own library card and many arms and legs, forever roaring with disbelieving joy even while going to the post office or waiting for a bus. Last night, however, the Philadelphia Phillies, proving themselves once again a team for the ages, punctuated their four games to one victory over the Tampa Bay Rays by eschewing the many-bodied bounce, instead breaking out the old-school suffocating bone-crushing mound-centered pileup, in which laughing bodies thump down horizontally one on top of the other until the guy in catcher’s gear at the bottom is dead or at least a little scared. The man pictured here played a key role in turning what could have become a many-bodied bounce into a pileup. Jesus Christ played a role too, probably the most important role, as He may or may not do in all things, depending on your understanding of the world, but in this case He worked in ways not quite so mysterious, or at least not mysterious to an amateur aficionado of sports celebrations such as myself. The pitcher who recorded the last out, Brad Lidge, dropped to his knees and stayed there, pointing and looking skyward, silently giving thanks to his personal lord and savior, as he did in a TV interview a few minutes later. This made the all-important first embrace between pitcher and catcher one that occurred with both men very close to the ground. They were not flat on the ground, however, until the third man in, the first baseman Ryan Howard, steamrolled the moment with the arrival of his hulking happiness (video courtesy of Josh Barron) . . . As you can see, once Howard clinched the mode of celebration with a hug so massive that it acted as a two-man tackle, everything else fell into line. A few seconds after the pileup starts, a windbreaker clad reveler stands outside the pile with arms outstretched for a hug from a figure sprinting in from left field, probably Shane Victorino, but the Flying Hawaiian chooses (or perhaps in such moments there really is no such thing as choice) to bypass the mere vertical embrace and instead flies onto the pile, arms and legs wide like a freefalling skydiver. I watched the celebration happily, thinking about my cousin Jamie and my friend David, both huge Phillies So I guess I follow sports in part to imagine an escape from this life's samsaric wheel of mistakes, an escape that peaks with the vicarious thrill of watching grown men celebrate. Sometimes, much more often than is healthy, I fantasize vaguely about enjoying a similar moment as a participant and not simply a watcher. When I was a kid I put these imagined celebrations in the context of sports, but I no longer do that. What could I win? What would it change? Everything, somehow. I’d laugh and curse and weep. I’d get down on my knees and give thanks. Or I'd plow into the moment like a building-levelling wrecking ball. Or I’d sprint in from left field and fly spread-eagle onto the pile. What would you do? Nino Espinosa

2008-10-28 05:51

The few cards I have from 1981, the year I turned my back on the Cardboard Gods, are an accidental monument to a moment so empty it was likely gone from my mind within hours after it happened, if not sooner. I must have a bought a couple packs, opened them, leafed through them. I must have been so far removed from feeling the magic of receiving brand new cards that I didn’t even notice the magic was no longer there, didn’t even remember there had ever been any magic. The cards from that year were as drab as the tile floor of a subbasement government waiting room, no sun anywhere, the color drained from the world that had been throughout the previous few years a brilliant synthetic rainbow. Nino Espinosa stands in opposition to 1981’s dull extinction of joy. I probably missed this while numbly leafing through the cards in the pack he came in. If I focused on anything, it was probably the backdrop behind him, a wall the color of nausea. Maybe I briefly noted his afro, the size of it by that diminishing year already an anachronism, but who was I going to tell about it? My brother was away at boarding school by 1981, and even before he’d gone away he’d been showing less and less interest in the things I wanted to show him. So into my shoebox of cards went Nino Espinosa with barely a glance from me, and a few years later, 1987, the house I grew up in was sold and into storage went the shoebox of cards. That year, 1987, I didn’t think that much about baseball or my baseball cards. I missed the news near the end of that year, Christmas Eve, that Nino Espinosa, member of the lovable and useless late 1970s Mets, member of what as of this moment remains the only World Series championship team in Philadelphia Phillies history, member of my sad tiny collection of 1981 cards, died of a heart attack at the age of 34. In fact I didn’t find out about his early death until this morning. We are all headed that way. The best we can do is stand in opposition to the fading of the magic, as Nino Espinosa does here in an ugly, off-center card, his loose, limber body exuding the feeling that things are just starting, that he's just getting warmed up, that the whole day is still ahead of him, waiting to be explored, waiting to bloom. Life, like the bulging preposterous afro of Nino Espinosa, will not be denied. Tony Perez

2008-10-24 10:15

I. If the Phillies are going to win the World Series this year, they are almost certainly going to need a well-pitched game or two from the oldest player in the major leagues, Jamie Moyer. How old is Jamie Moyer, you ask? III. IV. V. VI. Mike Schmidt (and Dick Allen) in the All-Time Franchise All-Stars

2008-10-23 06:21

Most people’s lives are like the history of the Philadelphia Phillies. Not all. Some lives are choked with triumph, I guess, and I guess other lives may seem to be so loaded with dramatic, wrenching failure as to be cursed. But if we are lucky enough to live a long life it’ll probably seem to most of us at the end as if there were long decades that went by without much happening at all beyond a slow, unstoppable accrual of losses. Who the hell were we all those years? And on that note, I present for your perusal and discussion the ballot for the Philadelphia Phillies All-Time Franchise All-Stars. As with the last time I presented this derivative feature (for the real deal, see Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Lineups), I’ll leave the ballot blank, in hopes of encouraging everyone to take a stab at filling out a lineup card. Before checking out the Phillies’ all-time pitching and hitting leaders at baseball-reference.com, try coming up with a list off the top of your head. That’s what I did, and it’s what made me realize I know far less about most of Phillies history than I know about any other major league team. I can name a couple guys from the 1915 pennant winners (Pete Alexander, Granny Hamner [author update: as pointed out in the comments below, Granny Hamner, despite his old timey name, somehow escaped existing in the deadball era and was instead a member of the 1950 Whiz Kids]) and a couple guys from the 1950 pennant winners (Richie Ashburn, Robin Roberts) and a couple guys from the 1964 team that collapsed in the pennant race (Johnny Callison, Richie Allen) and the rest of my knowledge about the Phillies is restricted to the team’s 1976–1980 golden age during my baseball-obsessed childhood, along with some vague recollections of players that came afterward, mostly those now suspiciously misshapen uglies from the 1993 pennant-winning team. With the above thoughts about the vagaries of Phillies history in mind, Mike Schmidt stands out more than any other player would in a consideration of an all-time franchise all-star team. Interestingly enough, however, he may not have been considered the best third baseman in franchise history until he’d been around for a while. First he had to surpass the feats of his 1974 home run leader counterpart, Dick (aka Richie) Allen, who while playing third base for the Phillies mangled National League pitching for several years during the very difficult hitter’s era of the 1960s. Apparently Allen was not a good fielder, however, while Schmidt was the best in his league for many years, and anyway Schmidt stuck around long enough to lead the Phillies to their only World Series victory and to pass Allen, and everyone, on most of the Phillies career record lists. (But the ever-underrated Allen does hold a lead over Schmidt in adjusted OPS+ in games played with the Phillies, 153 to 147.) The current edition of the Phillies, who took a 1–0 lead in the 2008 World Series last night, seem almost certain to fill out the other infield spots beside Schmidt on the franchise all-time all-star team before they’re done. Do they already deserve to be placed on the team? (Bonus infielder trivia: which now-retired Phillies shortstop once finished third in the MVP voting despite a .689 OPS?) And who’s your Phillies catcher? (Bonus catcher trivia: which two Phillies catchers represented the team the most times at the all-star game?) And which Phillies rightfielder (the one with the gun for an arm or the one who in some ways epitomized the hitters era of the early 1930s) ranks higher in Bill James’ rankings? And, most of all, is there a place for the Bull and Nails and One Nut? C: '77 Record Breaker (Reggie Jackson)

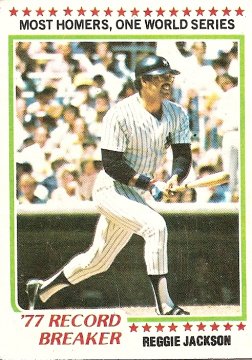

2008-10-22 06:21

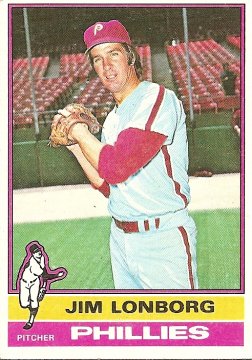

"By this time next week, B.J. Upton may have broken every playoff hitting record in existence." Jonah Keri, "This World Series is must-see TV" B.J. Upton’s homer-hitting pace in the 2008 playoffs—seven in eleven post-season games—has been astonishing, a pace that would net him 103 home runs in a 162-game season. But even if he somehow manages to keep up that pace during the World Series he still wouldn’t break the record depicted in this 1978 baseball card, not even if the series goes seven games, one longer than the 1977 World Series that Reggie Jackson owned. Has anyone ever owned a World Series more? Off the top of my head I can think of a couple other World Series characterized by the transcendently dominant play of a single player: Brooks Robinson’s 1970 World Series, and Roberto Clemente’s 1971 World Series. But when I run the blurry highlight reel in my head of those players leading their team to a championship I see them in a wider focus that includes at least one or two other players on the field. I see, for example, an Oriole first baseman receiving Robinson’s throw after another miraculous hot-corner stop, or a Pirate player scoring after a laser line drive off the bat of Clemente. On the other hand, when I think of the 1977 World Series, I think of Reggie, alone, reveling in the inarguable glory of Reggie. Good lord, what must it have been like to be Reggie at the moment captured by this card? [Author update: as noted repeatedly in the comments below, the moment captured in the card is clearly not from the World Series. D'oh!] You could argue that no one on a baseball diamond has ever been higher. Deciding game of the World Series. Biggest stage in baseball. Biggest city in America. Three pitches, three thunderous home runs. Certainly no one had ever been so high while also possessing the presence of mind—and the hulking ego—to pause magnificently and take in all the many details of the kingdom he’d just claimed: Reggie the conqueror, admiring the view from his unprecedented pinnacle at the top of the world. God, I hated him. But the world would have been flimsier without him. Jim Lonborg in . . . the Nagging Question

2008-10-20 07:04

"I tell you folks, it's harder than it looks. It's a long way to the top if you want to rock and roll." -- Bon Scott What is your general policy of rooting once your team has been eliminated? I think some people go with the thinking that if the team that beats them goes on to win it all, it makes their own team look better, so they root for their conqueror. Back in 2005, the last time the Red Sox were dethroned as World Series champions, I think I did actually pull for the team that dumped them, the White Sox, in the World Series, but not with much passion and mostly because I found something unpalatable about the Astros’ funhouse home ballpark. This year I certainly will not be rooting for the Rays, but that’s only partly out of bitterness. In truth over the course of their seven-game victory over my team (and the team the Phillies player pictured here is most often associated with), the Boston Red Sox, I came to understand that the Rays are just the better team, with more pitching weapons and a balanced, speedy, powerful, resourceful lineup. But then again bitterness may well have something to do with it, bitterness overlapping with my prejudice against young phenoms to whom success seems to come easily. This prejudice usually rears its ugly envious head when I read about some novelist in his early 20s getting a six-figure book deal and, it is implied (at least in my mind), more literary ass than a Breadloaf toilet seat, but I can also resent a team full of number one draft picks in their early 20s who have yet to really get stung by life, or so it seems. So I probably wouldn’t be rooting for them even if they hadn't bounced my team or weren’t playing against a team that I have long had a soft spot for, in part because I have some Philly area cousins who love them, in part because my parents lived in Philadelphia for a few years, in part because, as in 1993, the last time they made it to the World Series, they seem stocked with likable, fun-to-watch characters: Jimmy Rollins, Ryan Howard, the Flyin’ Hawaiian, 90-year-old Jamie Moyer, etc. Also, unlike Rays fans, Philadelphia sports fans know what it’s like to suffer. For them, as for most of us (but not for Rays fans in their brand-new finery), Bon Scott's words of wisdom ring true. . . All-Time Record Holders Runs Batted In

2008-10-17 06:52

I. II. "This is a fucking funeral," I said to my wife. "It is completely 100% over, done," my old friend Matt, from Greenfield, MA, said at about the same time, in an email. III. But a lot can happen in an inning. It was a sunny day. The man in the above card, to Hank Aaron’s left, a man who would go on to become a member of the Hall of Fame, lost two fly balls in the sun in the bottom of the seventh, nurturing an A’s comeback so improbable and unusual in its magnitude that it would not need to be referenced for 79 years. IV. "Do you want to sit here and listen to them lose or . . . , " she said. There are very few things that I would choose over the "or . . . " option, but one of those things, most of the time, would be to follow the Red Sox in the playoffs. But a loophole in that system of prioritization occurred to me. I am, in general, a short pitch-count kind of guy. "What the hell," I thought. "The most I’ll miss is an inning." As I rose off the couch, Pedroia knocked in the first run of the game for the Red Sox. We have a small apartment, so I could still sort of hear the radio call while "or . . . " was happening in the bedroom. I could not hear words, but I could hear Joe Castiglione’s voice rising again and again. Either the Red Sox were rallying or Joe Castiglione had abandoned the call of the game to pay tribute, for my benefit, to fellow broadcaster Phil Rizzuto’s work midway through "Paradise By the Dashboard Light." I got back to the actual words, and not merely the music, of the radio call by the ninth inning, the score knotted, and heard Masterson get out of a jam by inducing a double-play. I heard Youkilis reach on a two-out two-base error. I heard Bay get intentionally walked, just like the left-fielder who he replaced would have been. I heard Drew send one over the head of Gross, Joe Castiglione’s voice cracking orgasmically, as if he’d never seen such a thing in all his years. Don Zimmer

2008-10-16 06:32

For most of my life, most of Earth’s baseball fans viewed the team I root for in one or more of the following ways:

Since this last viewpoint was, unfortunately, by far the most obscure of the ways in which the team was viewed by baseball fans, the Boston Red Sox, in general, were not hated, not even when they were deserving of hatred. In general, they were viewed benignly, as an entity that did far more harm to themselves than they could ever do to anyone else. The team’s place in the baseball universe reached its pinnacle the year this card came out, when Don Zimmer presided over arguably the worst pennant-race collapse in baseball history. I can tell you from experience that Zimmer became a hated figure from within the world of Red Sox fandom (in Maine, according to a college friend, this hatred found its purest expression as something children called out when frantically running toward water: "Last one in is Don Zimmer!"), but outside that realm I think he was seen mostly as a comical figure, a crusty baseball lifer with bulging cheeks, beady eyes, and a history of debilitating, brain-scrambling concussions. Zimmer’s cartoonish persona came into full bloom a couple decades later as he served as a coach on Yankees throughout their dynastic domination of the league in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Zimmer’s transformation from a Red Soxian figure, i.e., one upon whom gentle mockery is cast, to a fully vested member in the Yankee Pantheon of Beloved Greats (Zimmer something of a junior member of the Pantheon’s "Colorful" wing along with, among others, Yogi Berra, Casey Stengel, and Phil Rizzuto) helped further define the team he’d once managed: If even Don Zimmer could find glory at the very top of the baseball world, then the message was clear: you went to the Boston Red Sox to lose, and you went to the New York Yankees to win. It seemed absolutely set in stone, something that could never change. Well, it changed. (Interestingly enough, it changed the year after Zimmer embarrassed himself by charging at Pedro Martinez during a bench-clearing incident in the 2003 playoffs, an attack that Pedro handled with the gentle flowing grace of the ever-peaceful, ever-beleaguered Kwai Chang Caine, but that’s a whole other story or two or three.) Anyway, it changed. Now, two Word Series victories later, the Boston Red Sox are considered by most of Earth’s baseball fans as an annoying huge-market monstrosity with arrogant, ubiquitous fans and a stranglehold on the mainstream media’s attention. Many fans wishing to damn them with the harshest terms possible point to the above developments to back up the claim that the Red Sox have become the Yankees. I’ll leave that claim alone except to say that I don’t see it that way. But I’m a Red Sox fan and have been a Red Sox fan since long before the birth of the young woman who sat behind me the last time I was at Fenway, in 2007, and talked on her cellphone the whole game about, among other things, how she was sitting near the "Penske Pole." Winning attracts a whole new breed of fan, I guess, one who doesn’t care so much about the game and couldn’t tell you who Johnny Pesky is, let alone that he got a raw deal in the eyes of the world for his role in the events of the 8th inning of the 1946 World Series, and this new breed of fan is one reason why fans of other teams have turned on the Red Sox, but I can only control my own fandom, and my own fandom is just like anyone else’s, and always has been: to root for my team to win. Anyway, it’s win or go home tonight against the team for which Don Zimmer is currently employed, the Tampa Bay Rays, who hold a three games to one lead over the Red Sox in the 2008 ALCS. For most of my life, the Red Sox would be viewed as roadkill by now. Even if they were the ones holding the three games to one advantage, it would be seen as a prelude to another choke job. Now baseball fans everywhere—those who hate the Red Sox, those who love the Red Sox, those who go to Red Sox games to talk on cell phones about the Penske Pole—have to temper the seemingly obvious conclusion that the Rays are the superior team with the thought that there is no tougher team to kill than the Boston Red Sox. If Dice-K, who looked so strong in Game One, wins tonight, then fearless Josh Beckett gets another chance to atone for his recent poor outings, and if Beckett wins then it’s Jon Deathbeater Lester in Game Seven. It could happen. These are the hated Red Sox, the team that threw down the old beady-eyed fool of losing long ago. Mike Timlin

2008-10-14 06:21

Perhaps it’s fitting that the only remaining member of the 2004 Red Sox yet to appear for the Red Sox in the 2008 playoffs now seems to be the 2008 Red Sox' last hope. If the Red Sox lose tonight, they will be down 3 games to 1, and though they found themselves at a similar disadvantage in last year’s ALCS and an even worse hole in the 2004 ALCS, it seems unlikely that they would be able to dig themselves out of such a hole once again. They pretty much have to win tonight. And to do so, they pretty much have to get a good game from Tim Wakefield. Wakefield has been my favorite Red Sox player for a long time. First of all, he throws a pitch so erratic and unpredictable it resembles life itself. Also, it is starting to seem that he has always been on the Red Sox (besides being one of the last of the 2004 Red Sox, he's also the last of the 1995 Red Sox). And I just like the way he quietly goes about his business. According to his peers, he has always been a great teammate, an attribute most famously on display in the 2004 ALCS playoffs, when he volunteered to sacrifice his game 4 starting assignment in order to save the bullpen in the 19-8 massacre in game 3, a sacrifice that is pointed to by his manager as a turning point in the series that was the turning point in Red Sox history. As can be seen in the following video clip from the immediate aftermath of the Red Sox World Series victory last year, no one will be rooting harder for Wakefield to come through tonight than the only other pitcher left from the 2004 squad: Rays at Red Sox, Game 3 ALCS Thread

2008-10-13 10:38

Last night, after a day of doing nothing, I watched a baseball game. It didn't feature the team I care about, but I had nothing better to do. During a break in the action I switched over to the football game. My television screen displayed a series of shots of angry fans, booing, many with their hands cupped around their mouths to better project the vocalization of their anger. Many wore the jerseys of the home team over their bulging, unathletic torsos. I had missed the moment that inspired the anger, and the announcers were choosing not to rehash it. It went on for quite a while, a stadium of people booing. I turned back to the baseball game without ever finding out why everyone was so unhappy. When I say I did nothing yesterday, I mean nothing did me. Nothing seeped in through the window and sat on my chest so I could hardly breathe. Nothing shoved pretzels down my throat until my stomach hurt. It was one of those suffocating Sundays. I didn’t want to do anything or go anywhere or talk to anyone, and I didn’t want to not do anything or not go anywhere or not talk to anyone. I read some Beckett, his novel Malone Dies. It’s about a guy sitting around his room waiting to cease to be. He occasionally uses a stick to drag things toward him, look at them, then push them away. Today, a work holiday, is shaping up as a repeat. But I have a baseball game to dissolve into later. I have been keeping score of games in these playoffs. What else is there to do. What else. I write the names of the Red Sox and of their opponents in my notebook, the one I fill with all my words, and I duplicate the action of each game with symbols and abbreviations. Every moment in this finite series of events will be recorded, as if it matters greatly, as if nothing could matter more. Rays Red Sox Red Sox at Rays, Game 2 ALCS Thread

2008-10-11 16:33

In my mind the foremost of the devils masquerading as innocuously innocent "rays" is the one from Scott's adopted country, Australia (which his Scottish family moved to when he was a wee lad). Last night, Australian Grant Balfour sailed one of his near-100-MPH heaters in the direction of J.D. Drew's head. It was a situation that called for Drew to be walked, either intentionally or as a result of pitching to him very carefully. From the reaction of players in the Red Sox dugout, it seems possible that Balfour decided one pitch could do just as good a job of putting Drew on base as four pitches, with the added bonus, perhaps, of letting them know you're there, something the chirpy, hard-throwing Balfour proved capable of during the Rays' divisional series against the White Sox. Here's hoping that the Red Sox can channel the great Bon Scott tonight as they provide a reply to such challenges. Lineups, courtesy of The Boston Globe: Red Sox Rays Brendan Harris (So You're Thinking of Jumping on the Tampa Bandwagon)

2008-10-10 07:35

I am a baseball fan of a team whose season has come to an end. I am considering transferring my rooting interests for the duration of the 2008 playoffs to the Tampa Bay Rays. They seem to be a scrappy low-budget band of likable underdogs who only a bitter societal misfit with crackpot ideas and a psychotically narrow agenda could dislike. Are they not every bit as strong a testament to the human spirit as the team that is held up as the sporting world equivalent to the first moon landing that occurred during that earlier team’s miraculous push toward a championship, the 1969 Miracle Mets? If the Tampa Bay Rays can go from nowhere to a championship in a single season with a team of nobodies who collectively earn as much as one or two of the celebrity superstars from the domineering money-laden title-hogging franchise they are facing in the American League Championship Series, then couldn’t you begin to argue that anything is possible? We will walk on Mars! We will have world peace! We will all get laid by swimsuit models constantly! Why, I ask you, should I not root for that? Sincerely, About To Leap Onto The Tampa Bay Bandwagon Dear About To Leap, I am probably the wrong person to ask this question, since I would root against any team opposing the Boston Red Sox, the team I have rooted for my whole life, even if that opposing team included Gandhi, my mother, several 9/11 firefighters, and my cats. But since you asked, I will provide my thoughts on the matter. First of all, the Tampa Bay Rays should not be considered the underdog in this series. They not only finished ahead of the Red Sox in the American League East, they beat them in the season series 10 games to 8. When the Red Sox had a chance to apply pressure to them with a series at Fenway Park late in the season, the Rays took two out of three. Furthermore, the Rays come into the series with key players who earlier sustained injuries, such as Carl Crawford and Evan Longoria, now healthy, while the Red Sox are limping, reigning World Series MVP Mike Lowell out for the series and ace Josh Beckett iffy. Of course, no season occurs in a historical vacuum. The Red Sox have been a prominent playoff presence since 2003, and are the only team this decade to win two World Series. On the other hand, the team they are facing has been so bad for the entirety of their existence until now that it is almost like they have not even existed. My response to that line of thinking is that they haven’t existed until this season. This is the first season of the Tampa Bay Rays. And this is not just me saying it. Last November, the owners of the team disowned any connection to anything previous to this season by throwing the original name of the team, the one that had suffered a losing record every year of its life, into the dumpster. (After the name change, the next move by the team was to ship the member of my Golf Road collection pictured here, Brendan Harris, to Minnesota along with Delmon Young, a move that identifies Brendan Harris as one of the last true Devil Rays.) The Red Sox have been in the playoffs five out of the last six years, which is pretty good, but it’s not as good as the one hundred percent success rate of the Tampa Bay Rays. So they are not the same team that endured all that suffering. Why are they not the team that endured all that suffering? Why did they change their name? Apparently, some market research was done that found that the name "Devil Rays" was less marketable than "Rays." Even if this decision to change the name was not due to pressure from religious groups objecting to the word "Devil," a scenario that seems highly likely to me in this age of rampant fundamentalist idiocy, the name change would still rub me the wrong way. If market research had been done on the name "Mets" before the 1969 season, it surely wouldn’t have "tested" very high either, but part of the reason that season has caught the imagination of so many sports fans is because it was the New York Mets that won it all that year, the exact same team that had been so bad for all of its existence, and not the New York Thunder or New York Rage or New York Conquering Black-Clad Charismatic Sharp-Fanged Predators. But even if you swallow the premise that the Tampa Bay Rays are a continuation of the version of the team they tried to revise into invisibility, I ask you: just how much did they and their fans suffer? First of all, what fans? The team couldn’t even pack them in for most of this year, let alone in previous years, so it’s not exactly like they have a legion of deeply-scarred devotees who are on the weepy brink of finally seeing all their wildest dreams come true. Second of all, it’s not as if there are a lot of guys on this year’s team who have endured year after year after year of defeat in a Tampa Bay uniform. These guys, by and large, are newcomers, unburdened by history. Most of them are young and have been leaping from triumph to triumph throughout their lives. What suffering? In fact, these guys, the Tampa Bay Rays, are more of a collection of "chosen ones" than the team they are facing for the American League pennant. Out of their regular nine-man lineup, the four-man pitching rotation they will use for the series, and the six bullpen pitchers most likely to get called on to record crucial outs (i.e., their nineteen key players for the series), they have ten former number one draft choices. The Red Sox, by comparison, have five former number one draft choices manning those corresponding spots, and two of the five, Drew and Lowrie, didn't even start all four games of the recently concluded ALDS against the Angels, while a third, Varitek, was pinch-hit for in a big spot, showing his diminished role on the team, and a fourth, Beckett, has been reduced by injury questions from an exclamation point to a big question mark. I realize, of course, that it would be preposterous to argue that the Red Sox, a giant-market juggernaut with virtually limitless financial resources, are at some kind of a fundamental disadvantage against the tiny-market, inexperienced Rays. But when I think about the Rays I think about standing around the sidelines before a pickup game as a kid. Two big kids are choosing up sides. They pick the best players first, the cool kids, the handsome kids, the kids without glasses or braces or odd personality quirks. Meanwhile, most of us have to stand there and wait to get picked, our worth in the eyes of our peers on graphic display for everyone. If you’ve ever had to stand there waiting and waiting to get picked, you have felt the sting of disappointing life. So why would you be so eager to jump onto the bandwagon of a team full of young elites who have never had to deal with that devil? *** Note: The Griddle will be carrying the Baseball Toaster game thread for tonight's first game of the American League Championship series between the Red Sox and the Rays. Darold Knowles

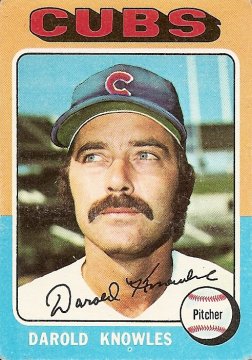

2008-10-08 06:25

"Get ready; ninety-nine years . . . The wait is over. This IS the year!!" – Quote by the sponsor of the baseball-reference.com Cubs page OK, let’s start at the top of the card for answers. Maybe it’s the name. The sound of it. Cubs. The hard C collapsing immediately into the short glum "uh," which gives way to the stubbing, stunting B sound, which reduces whatever power might have been the sound of the name of the long-suffering team to a sibilant, trailing-off S sound, a weak hissing like the last gasp of a broken radiator in a car on the side of a highway, other cars flying past, the drivers of those cars all thinking the same thing as they notice the poor sap peering into the smoldering open hood of his car: Glad that’s not me, stranded, fucked. Yes, maybe it’s the name. Cubs. Or maybe it’s the cap, represented here not by a photographed image but in a version imagined by a Topps artist and superimposed on a photograph. The imaginary version of it is in a certain way more real than the real version in that it highlights a certain key aspect of the Cubs cap, a cap that has been the same for as long as I have been alive. It looks, atop the head of Darold Knowles, more like somewhat sloppily applied cake icing than a cap. It looks like you could eat it, like you could dip your finger into the blue and red and get yourself a nice quick sugar high. Their real caps don’t look like this, not exactly, but maybe there is something in the cap, in the mild, friendly blue, in the taming of the racier red by restricting it to the confines of the basic spelling-block C, that invites a kind of metaphorical dipping of the finger into the icing. Maybe other teams, without even knowing it, look across the diamond at the Cubs and assume the attitude of a guy walking through an empty break room at work and noticing a cake just sitting there, waiting to be violated. Or maybe, going lower on the card, to Darold Knowles’ face, it’s the feeling of doom. I don’t believe that teams are ever cursed, but I do think, and actually know from my own experience as a Red Sox fan, that year after year of disappointment and defeat tends to make one worry whenever victory seems close at hand. How is it going to go sour this time? What new unscarred section of my heart is going to get ground to bits this time? The nervous murmuring in the stands, along with the constant references to curses and droughts in the media, filters down to the members of the team. How could it not? How could it not in their weaker moments make them feel like Darold Knowles seems to be feeling now? He seems to be aware that something gloomy and horrible is descending, big and invisible, impossible to stop. To turn back the tide on all that, the name, the cap, the feeling of doom, you need to face it head on, I think. Lou Piniella, current manager of the Cubs, seemed to explode whenever asked about the last sad century of the Cubs. I think this strategy, trying to ignore the elephant in the room, getting angry whenever anyone mentions the elephant, is only going to make things worse. When the New York Rangers toppled their Cub-like demons in 1994 they did so by following the lead of Mark Messier, who embraced, rather than turned away from, the burden of history. They also did so by having a fantastic team, which of course is the first prerequisite to slaying curses, but the Cubs had a fantastic team going into these 2008 playoffs, possibly the best all-around team in baseball, and they got bounced in three games, playing tight, as if they had all seen the dark cloud that Darold Knowles seems to be seeing. Angels at Red Sox, Game 4 ALDS Thread

2008-10-06 16:49

So far, three games into this 2008 American League Divisional Series between the Angels and the Red Sox, the team that has been On the Road has won every game. Maybe there’s no place like home, and not in the way that Dorothy meant it. I mean maybe home does not exist. Where is home? Jack Kerouac boomeranged back and forth across the country for years trying to answer that question. Maybe he only ever felt at home when he was in motion, on the way from one thing to another. By the time he arrived, whatever he thought he’d come for had evaporated, if it ever existed in the first place. My home is in Chicago, sort of, where I reside, but it is also in Vermont, sort of, where I grew up, and in New York City, sort of, where I lived for years. Sometimes people assume I’m from Boston, because of the Red Sox cap, but the truth is I don’t know that city very well. I went there every once in a while as a kid, a little more often when I spent a couple summers on Cape Cod during high school, then I lived there for a few months in the fall of 1985. The last time I was there was for the parade in 2004, which I’d always promised myself I’d find a way to attend, so that I could scream and yell and cry with strangers. Last night I watched the Red Sox game in a bar here in Chicago where I watched the Red Sox win the first World Series of my lifetime. Then, the place was packed with Red Sox fans, backing up the reputation it has for being a Red Sox bar. When Foulke fielded the last grounder everyone went berserk. Things have changed. Last night the place was half-empty, pockets here and there of laughter-barking late Sunday football lushes who either didn’t care about the Red Sox or who were sick of them. The moment I walked in some drunk spotted the Red Sox cap on my head and bellowed, "Nice hat! Do they make it for men?" But this is not my city. Why should I be surprised when I don't feel at home. I wouldn't feel at home in Boston either. Who cares? Just let me read my books and follow my team in peace. So on that note, tonight I’ll be rooting for the home team from behind the locked door of the unit where I currently pay my rent and pet my cats. Go, home team. Angels Red Sox SP: Lester Joel Youngblood

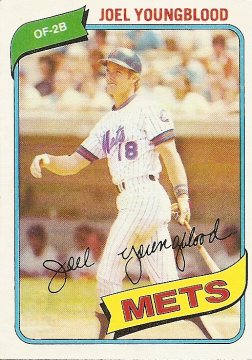

2008-10-05 09:18

". . . and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old . . ." – Jack Kerouac, On the Road I can deal with Greats getting old. When I was a kid Old Greats shilled for coffee makers and lite beer on TV and showed up every so often at the ballpark to wave at the crowd, who roared with tears in their eyes at the Old Greats for their glorious pasts and for continuing to elude the grave. I learned that this is what happened to Greats: They became Old Greats. This prepared me for the subsequent graying and balding and widening and stiffening and bejoweling of Greats from my youth such as Seaver and Bench and Reggie and Schmidt. But when a member of the Cardboard God rank and file suddenly shows up out of nowhere looking old or, worse, dies (as, for example, Ed Brinkman did last week) I feel it a lot more intimately than when I see, for example, that Gaylord Perry has no hair. So if you happen to know what Joel Youngblood looks like these days, don’t tell me. I don’t want to know. To me he’ll always be like he is here, his helmet hiding his premature baldness and preserving his look of glowing youth and vitality. I guess he played for several seasons after this 1980 card, lasting all the way until 1989, but to me he was always one of my two or three favorite Mets during that time in the late 1970s when my affection for the Mets was at its height. As I’ve mentioned before, I always followed the Mets intensely for two weeks every summer during visits from Vermont to see my dad in New York. Dad kept his small black and white television in the one closet of his studio apartment, but he let us take it out to watch Mets games, and for some reason I always associate those viewings, the television propped on a wooden chair, my brother and me sitting on big pillows on the floor, Dad at his desk listening to Bach on headphones, his eyes closed, no interest in the game whatsoever, the three of us about as close as we'd ever be, with Joel Youngblood. In this card Joel Youngblood wears the number 18, a number which, just a few years later, as it festooned the tight mid-’80s uniform of Youngblood’s number heir, would seem to be targeted for sure retirement by the franchise. If you ever sat in Shea and watched Darryl Strawberry blast a home run off the scoreboard in right field you know what I mean. He seemed to have an invincible talent. But nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody, and after years of drug addiction and legal problems for Strawberry the number 18 remains officially eligible for further use by the team. I think Strawberry showed up last week for the closing of Shea Stadium. I’m not sure if Joel Youngblood did. It looked, just a couple weeks earlier, like the Mets would extend Shea’s lifetime beyond the end of the regular season by banishing the aftertaste of last season’s collapse with some playoff baseball. But you can never count on anything, so Shea’s last moment was not a playoff game but a bittersweet ceremony in the cold dusk featuring a gathering of Old Greats and Old Pretty Goods and Old OKs. The stands must have looked ragged, forlorn, many too disappointed to stay and watch. As the Allen Ginsberg stand-in in Dharma Bums put it, "It all ends in tears." * * * (Note: The Griddle will be doing the game thread for tonight’s Angels-Red Sox game.) Red Sox at Angels, Game 2 ALDS thread (plus more Kerouackian pregame rambling)

2008-10-03 14:09

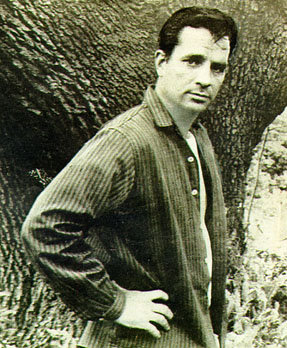

“My position in the current American literary scene is simply that I got sick and tired of the conventional English sentence which seemed to me so ironbound in its rules, so inadmissable with reference to the actual format of my mind as I had learned to probe it in the modern spirit of Freud and Jung, that I couldn’t express myself through that form anymore.” – Jack Kerouac, 1959 After his first novel, The Town and the City, a conventional family saga, Jack Kerouac (shown at right in a portrait of the artist as a young excellent athlete) tried and failed for years to find a way to tell the next story he wanted to tell. Finally, all the stops and starts got to him and he had to go away to the loony bin for a little while. This seems to have been the turning point for him. If he kept trying to follow the rules of writing not only was his novel doomed but he was doomed, too, so into the typewriter went his teletype scroll and for three weeks in 1951 he let the sentences come out long and gasping and searching and ragged and real, until he had something brand new, so new, in fact, that it would be six years before anyone would be willing to publish it, six years to roam the land with On the Road unpublished, but our October hero though deeply disappointed and hurting in the end didn’t care because he had found the answer, sing your song and rules be damned, and into the hopelessness of the rule-bound world he flung creation after creation, Visions of Cody, Doctor Sax, Maggie Cassidy, Mexico City Blues, The Subterraneans, Tristessa, all unpublished until the calamitous “overnight success” of On the Road in 1957, the author in those wandering years a nobody for real, but one who knew joy because he’d found a way to love the world and sing that love in sentences that tumbled and wheezed and collapsed and somehow rose from collapse to stand unsteady but with eyes agleam, like a drunk nobody noticing the tender ache of the soft violet sunset as the railroad cops advance to drag him to the hoosegow, where he’ll weep with thanks for what he’s been lucky enough to see. Yes, Jack Kerouac loved long unruly sentences. Maybe this love can shed some light on why the author, an avid sports fan, seems to have loved baseball above all other sports, even though one of those other sports, football, had given him renown as a hometown hero and a scholarship to play big-time college football for the famous coach Lou Little at Columbia University. Football, if translated directly into sentences, would be short, blunt declaratives. Baseball into sentences? Something else altogether. . . If Jack Kerouac were alive today—and he could have been alive today maybe if he’d lived a healthier life, if he had, as aging legendary Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki suggested when Kerouac and Ginsberg came to meet him, laid off the booze and instead went with green tea, he’d be a strong thin old cuss of 86, still a decade shy of D.T. Suzuki’s lifespan of 96 years, but he didn't heed the advice from Japan which will relate (Japan I mean) in a moment, and so Jack Kerouac has been dead almost as long as I’ve been alive—he’d be watching the playoffs and the Red Sox in particular though I guess it’s possible if he was still living in Florida where he did kick the bucket maybe he’d have migrated to the Rays but I hope not and anyway maybe the green tea would have cured him of his need to lay around Florida waiting to die and he would be living in a monastery in northern California and would have left the monastery to venture down to Anaheim for prime literary lion seats near maybe a vacationing Stephen King and the two could compare notes on weirdo literary groupies while adjusting their scorecards between innings after confusing double-switches, and in this scenario, Jack Kerouac alive, I’d have to think his favorite Red Sox player would be Daisuke Matsuzaka, tonight’s starter, and not just because he was Japanese, like D.T. Suzuki who saved (in this reimagining of reality) Jack Kerouac’s life all those years ago but also because Jack Kerouac loved long ridiculous sentences and Dice-K, if he were not a baseball player but that structural unit of prose called a sentence, would be the longest, strangest sentence in the 2008 Red Sox novel, digressions and misdirections and ballooning parenthetical flowers of ideas within things within ideas within things within ideas until the whole dream of existence is revealed as an infinite loom of wanting and mercy and lightning and gloom interwoven and unraveling all at once and you the reader the solitary lonely alive fanny in the stands begin to wonder if there is even a purpose anymore and all there is left to rely on is the rhythm below the endless looping expansions toward mu (the Japanese word meaning nothing), the sentence possibly doomed, who knows and after all can’t it only ever end in a question? In a jam, bases loaded, full count? Into the pretzeling contortion the trouble-master goes slow and calm as ever, implacable, and out of his hand comes an unpredictable pitch, impossible to know what will come, same as life, so hang on and rejoice: it’s Dice-K’s turn. Red Sox at Angels, 6:37 PT, 9:37 ET Lineups (tonight sadly lacking an echo of Kerouac's hometown), courtesy of the Boston Globe: Red Sox Angels Terry Hughes

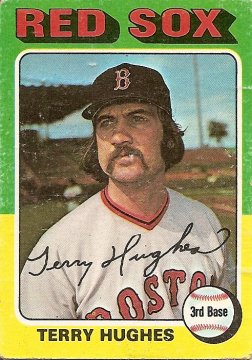

2008-10-02 06:25

I finished re-reading Jack Kerouac's Dharma Bums for the half-dozenth or so time on the long commute home from work last night. This reading of the book, which I don't think measures up to Kerouac's opus, On the Road, but which has what I find to be an extremely touching sincerity and a frail, delicate beauty all its own, was colored by my reading, immediately beforehand, of Jack's Book, an oral biography of the author that concludes by charting his long sad retreat from the guileless embrace of life that colored his early years and his greatest prose. He died a bloated housebound wino watching television in the afternoon, crippled by fame and bitter and tired of life at the age of 47. I knew this already, but had never seen it so intimately described, with the words of those close to him, so this time when I read Dharma Bums, a book that ends, literally, with him coming down from a mountain, I couldn't help but sadly see the clues to his eventual ruin everywhere. He is, in that book, already starting to drink too much. More generally, there is something in his version of buddhism, as opposed to the always-engaged-with-life buddhism of the co-star of the book, Japhy Ryder (the poet Gary Snyder), that speaks of a deep wish to negate the pain of the world by negating the world. Hints of a return-to-womb mentality, a curl-up-and-die mentality. The beauty of the book comes in the tension between the author's growing wish to pull the plug on the Whole Cosmic Show and his deeply felt love for all creatures great and small, his sincere attempt to love every inch of this world as if it were heaven already arrived. The book ends with him coming down from the mountain, but since I know that what happens after that descent is a sad reversal of the zen saying, quoted in the book, "when you get to the top of the mountain, keep climbing," I want to focus on the beginning of the book, which I mentioned yesterday, Kerouac's stand-in Ray Smith noticing and drawing out the thin little St. Theresa bum. When you stop noticing the people and things in the margins of life, you might be on your way to a general creeping darkness, the world disappearing from your weakening grasp. So here is the marginal Terry Hughes, who played a few games for the Red Sox in 1974. Does anyone ever mention him in the litany of Red Sox names? Has anyone ever asked him if he's got a special prayer? Also, why so glum, Terry? And where did you get your haircut? And whither goest thou in the fading October light with your droopy features and baggy eyes? * * * Some more random thoughts about my Bosox. If in April I was told the following, I would have assumed I'd not be staying up past my bedtime to watch playoff games in October: 1. The starting pitcher who dominated all last season and into the playoffs is going to be hurt a lot and will be generally less effective, then at the very end of the year he will sustain an oblique injury. Angels-Red Sox Game 1 ALDS thread

2008-10-01 13:36

Last year, the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, the Red Sox traveled a distinctly Kerouackian path to their second World Series title in four years. Leave it to a blog devoted to poetry to point out many of the echoes of Kerouac sounded by the Red Sox' 2007 victory, including not only that the Red Sox clinched the series “on the road” but that they did it in Denver, hometown of primary Kerouac muse Neal Cassady, and that they were led by their third baseman, the World Series MVP, whose last name happens to be the same, Lowell, as the Massachusetts town where Kerouac was born and raised. The famous traveler’s first trip out of Lowell may well have been the time, in 1933, when his father took him to Fenway Park to see the Red Sox play. |