|

Monthly archives: May 2008

Cardboard Books: A False Spring

2008-05-30 06:10

"It was a land of horizons." – Pat Jordan, A False Spring The first maps of the world I ever studied were the ones comprised of lists of place-names and numbers on the backs of baseball cards. Some of those maps, the ones on the backs of the best cards, contained only the names of cities I knew. Major league cities. Other maps, the ones on the backs of the untested, the mediocre, the obscure, had places I’d never heard of. The bottom line of statistics on every card totaled only the numbers accrued in the major league cities. Accomplishments in unknown towns didn’t count. Looking at these maps, I began to understand that the world had horizons, edges, and that it was possible to drift beyond the horizon, where nothing mattered. More troubling still was the nature of many of the maps of the least of the Cardboard Gods, where the list of place names flickered back and forth again and again between major and minor, between known and unknown, between counting toward the total in the bottom line and not counting at all. These complicated maps suggested terrain where the borders are impossible to discern. You won’t even be able to tell when you’re walking off the edge of the world. Pat Jordan should have been one of my Cardboard Gods. Many of the players he played with and against as a young man in the minor leagues made it onto the baseball cards I collected as a kid in the 1970s, but few of them matched his raw talent. He threw hard when he entered professional baseball as a sought-after 18-year-old bonus baby, and he threw even harder when his still developing frame filled out the following year. Like many flame-throwing phenoms, he often struggled with wildness, but on those days when he had command of his pitches he was dominant, nearly unhittable. To that point all the baseball stories that had been told, all the maps of the world that had been made available to baseball fans, suggested that Pat Jordan would one day have a baseball card showing his walk totals and ERA decreasing from year to year as the darker edges of the world receded. He would be featured on a baseball card that had no room on the back for minor league cities, no room for oblivion, no room for doubt. Jordan was not the first to live a coming-of-age baseball story that went in the opposite direction, toward ever-greater oblivion or doubt, but he was the first to tell about it. In his classic memoir, A False Spring, he provides a map of uncharted territory that remains every bit as arresting today as when the book first came out in 1975. Since that time, narratives about the fringes of professional sports have become more familiar—as I read Jordan’s book I was reminded at times of both Slapshot and Bull Durham. But when these films came to mind (in the former when Jordan describes how all the minor leaguers at spring training would gather in the morning to watch a television fitness show featuring a limber, voluptuous female host; in the latter when Jordan describes his Nuke LaLoosh-like desire to stubbornly blast brainless fastballs by everyone) Jordan’s version of the minor leagues always seemed by comparison darker, more painful, more real. This is not to say that the book is without humor, or that its sharp, harrowing focus on the failures of a young, unhappy loner precludes a rich and varied cast of characters. We see future career hit-by-pitch-leader Ron Hunt as a teenager who calls every older woman in his life "Mom"; we hear of a player who disappears from the team one day after it was discovered (by a young Phil Niekro) that he’d been cheating his teammates at poker; we get to spend time with a beer-swilling minor league manager named Bill Steinecke, who conducts the following seminar in the middle of a game after noticing that his players don’t seem to comprehend a remark he just made about sex: "I don’t suppose any of you know what I’m talkin’ about? No, I expect not, You think it’s just push-push and goodbye, huh? Well, Podners, it’s time you got educated. With a woman you gotta do things. Make them happy, too." And then, while we listened with rapt attention—and the opposing team loaded the bases—Bill gave us our first course in sex education. His course was very thorough, touching all the bases: physical (various positions, unusual acts), anatomical (a description of the female body); medicinal (prevention of disease), and psychological ("Make them happy, too.") It was very graphic and, at appropriate moments, punctuated by darting little gestures of his tongue, while his eyes, no bigger than Le Suer peas, gleamed. (p. 115) Of course, the most vivid character of all, thanks to the author’s refusal to varnish anything about his younger self, is the one glowering in the photograph at the top of this post. Throughout A False Spring the young man simultaneously unraveling and growing up at the center of the action comes across as immature, arrogant, even unlikable. Early on, his recounting of his high school career suggests that he cared very little about his teammates, thinking of them as useless background figures in his quest to get a big signing bonus from a major league team. Upon entering professional baseball he expands this general disdain into a complete lack of interest (when he’s not pitching) in whether his team wins or loses; in fact, he roots against the success of other pitchers on the team. Outside the ballpark is not much better, his aloofness setting him apart from townspeople and his teammates, his lack of social skills making many of his rare interactions awkward, even ugly, such as when he approaches two older teammates talking to local girls on the street and asks, loudly, "Who’re the cunts?" He’s not an easy figure to root for, but you begin to root for him like you would root for yourself. You too were once young, arrogant, awkward, self-centered. You too once thought you’d live forever, that the fastballs would paint the corners, that doubt and oblivion would dwindle then vanish, that the winning would find a way to start and never end. Off in the distance is the dream, a big league callup, and there are days when you feel young and strong, and those days the dream seems close, a sure thing. Other days, the majority of days, you can’t find the strike zone, you feel yourself getting older, weaker, ever more uncertain, you pass the empty hours roaming aimlessly and alone. Here is the challenge laid down by A False Spring, by all great books: Stop dreaming. Open your eyes. Welcome to the land of horizons. Brian Asselstine

2008-05-28 05:55

Meeting Chair: Josh Wilker Attendees: Anger, Going Through Yet Another Heavy Bob Dylan Phase, The Pretentious Promoter of the Hackneyed Voice of Childhood, Apocalyptic Panic, Disgust, Compulsiveness, The Baseball Guy, The Guy Who Loathes Josh Wilker Could Not Attend: Easily Inspired, Zen Calmness, Humor, Confidence Agenda: Brian Asselstine Profile Remarks: Josh Wilker (Meeting Chair): Thanks for coming. I well understand the tedious nature of these meetings, and I appreciate your sacrifice. Anybody got anything? The Guy Who Loathes Josh Wilker: Why are we even here? I’ll tell you why. Because you can’t handle what is a one-person job, if that. Give a monkey a typewriter and he’ll do better than you. You’re a disgrace. You didn’t even spring for donuts! Compulsiveness: All I know is we’ve got to get something up there on the site today or . . . or bad things will happen. Anger: [Glares at previous speaker] The Baseball Guy: Can’t we just string together a paragraph about Asselstine’s brief, mediocre career and call it a day? The Pretentious Promoter of the Hackneyed Voice of Childhood: But surely there must also be some way to connect to the realm that the poet Rilke declared to be the wellspring of all great art, the numinous pastures of long lost memory, where innocence and wondrous awareness combine to— Anger: [Lands punch in previous speaker’s solar plexus] The Pretentious Promoter of the Hackneyed Voice of Childhood: Oof! Compulsiveness: What about something about his facial expression. Oh, I wish Humor was here to quickly come up with something about how he looks like he’s evacuating his bowels. Is that funny? Disgust: Yes, yes, let’s produce yet another This Guy Looks Like He’s Doing This Instead of What He’s Doing essay. That will surely add to the advancement of civilization. Going Through Yet Another Heavy Bob Dylan Phase: (humming) Goin’ to Aaa-ca-pul-co, goin’ on the run . . . Apocalyptic Panic: Disgust is right. Civilization is doomed and we’re here trying to write about the baseball card of a guy taking a swing in a batting cage thirty years ago with a look on his face like he just hit another warning track flyball and he’s worried that his failure to go any deeper than that is going to banish him back to the minors, doomed is sort of what he looks like, as if he’s us with the soaring gas prices and melting ice caps and endless war and teenagers getting shot every two seconds and— Josh Wilker: Uh, did anyone else notice the heart shape on the left shoulder of Brian Asselstine’s uniform? That’s kind of odd, I thought. The Pretentious Promoter of the Hackneyed Voice of Childhood: Yes, perhaps we can weave together some sort of heartrending narrative that touches on whence the tender touch of romantic love first—oof! The Guy Who Loathes Josh Wilker: Don’t try to change the subject with your pedestrian observations, Josh Wilker. You’re worthless. You add nothing to the world but just sit there eating tortilla chips and watching sitcoms. Disgust: My stomach. The Baseball Guy: I know nobody at these meetings cares what I have to say, but don’t most people who might read whatever we come up with want to read about baseball? Disgust: Is there a gas leak in here? Compulsiveness: How about instead of a regular essay we just slap the meeting minutes up there? Disgust: [Vomits] (Love versus Hate update: Brian Asselstine's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Jerry Koosman in . . . The Franchise All-Time All-Stars

2008-05-26 09:00

In honor of today’s military-minded holiday, here’s a card featuring a player who served (stateside, I believe) in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. The card also happens to have been one of my favorites when I was kid, a great action shot of a guy who seems with his balance and his powerful legs and his rubbery upper body to have been made to be that poised human whipcrack known as a major league pitcher. From the position of his wrist it looks like Koosman’s about to snap off a 12-to-6 curveball. I don’t know what pitches Koosman threw, actually, but I know he was good at throwing them, helping the Mets to two pennants and one World Series. Two years before this card he won 21 games and finished second in the National League Cy Young voting. The following year, when this photo was snapped, he went 8 and 20. But here he is, in the midst of that dismally unlucky season, showing perfect balance. Can you stay balanced during the bad times? I guess that’s the key. Koosman could. The year of this card he had another lousy won-loss record, 3-15, which dropped his all-time record with the Mets to just three games over .500, and the Mets traded him away in a move that reduced the number of members of the 1969 Miracle team remaining on the squad to one, the invincible Ed Kranepool. The Mets had been floundering since Tom Seaver had been jettisoned the year before, but the trade of Koosman truly closed the book on the Mets’ first golden age while, in a pleasing twist, opening the door just a crack for their next golden age. Koosman had recorded the final out of the Mets’ first World Series win, and the minor leaguer he was traded for, Jesse Orosco, would record the final out of their second World Series win. But Orosco, who would become a very important figure to me—the last strand of childhood—for being the last Cardboard God to hang up his major league spikes, is a story for another day. Today I want to just do some holiday blabbing about Jerry Koosman, who kept his balance through the last couple unlucky years with the Mets and was able to stick around long enough for the wins to start coming back to him on the Twins, winning 20 games his first season with them and 16 the next. He dropped off the following year, and the Twins dumped him for Randy Johnson, who unfortunately for the Twins was not Randy Johnson. Koosman soldiered on, winning 11 games both of the next two years, the latter effort helping the White Sox post the best record in the major leagues in 1983. He hung it up two seasons later with 222 lifetime wins. A consideration of Koosman’s estimable career, combined with thoughts sparked by the thought-sparking saint of baseball blogdom, Joe Posnanski, who a few days ago wondered who was the best everyday player the Mets have ever had, has inspired a new, hopefully recurring, feature here on Cardboard Gods in which I will ask readers to chime in with their picks for the all-time best team for every franchise. (I'm certainly not the first to ever think of fooling around with this idea; the great Rob Neyer riffed on the idea in producing one of the most entertaining baseball books ever written, The Big Book of Baseball Lineups.) I decided to start with the Mets, figuring that their fans could use an opportunity to dwell on the good times in the past, what with the present fortunes of the team looking so gloomy, losses mounting, the guillotine seemingly inches from the neck of the cornered manager. C: Mike Piazza Wild card: Ed Kranepool *** (Love versus Hate update: Jerry Koosman's back-of-the-card "Play Ball" result has been added to the ongoing contest.) Don Stanhouse

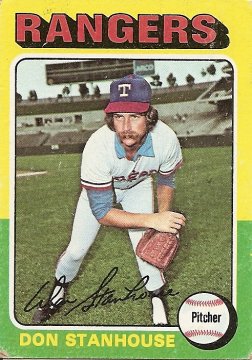

2008-05-23 07:49

I never picked up a woman in a bar, or anywhere else for that matter. For years I went to bars every weekend, praying something would happen, but I just got drunk and stared. I stared at the jukebox lights, at the bottles behind the bar, at my own reflection in the mirror behind the bottles, at whatever increasingly creeped-out women happened to be within eyeshot. It hadn’t been much different earlier, in high school and college. It’s something of a miracle that I ever escaped virginity. Once in a while I shoved poetry at women, but this only worked once, in China, with a woman who didn’t have a very strong grasp of English. Maybe I should have, as I am learning to do now, looked to my baseball cards for guidance. This 1975 card would have been a good place to start. It doesn’t take much imagination to envision Don Stanhouse in this same pose in a 1970s nightspot, his bent right elbow not faking a follow-through but leaning on the back of a pleather booth filled with tipsy secretaries. "Hey ladies," Don Stanhouse croons, neck medallions dangling, "how you all feelin’ tonight?" Paul Mather in . . . The Nagging Question

2008-05-21 13:55

Early in Hang Tough, Paul Mather, three kids in little league uniforms stop on their way to a game to talk to two brothers who have just moved to town. The younger of the brothers starts bragging about his older brother’s pitching abilities. The three uniformed boys are skeptical, and when the older brother at first refuses to show them what he can do, they begin to mock him. He holds the ball they’ve handed to him. It feels good in his hands. Too good. I was reading this scene on the subway this morning. I’d read it dozens of times before. Even so, I started to get tears in my eyes. By this point in the novel, it has become clear that the older boy, Paul Mather, lives for baseball. But there have been hints of a serious medical problem. He’s not supposed to be playing any baseball, not until he gets permission from a new doctor, a specialist the family has moved across the country to be near. I didn’t think of Hang Tough, Paul Mather during Jon Lester’s no-hitter two nights ago, but the connection between the real and fictional pitchers began to dawn on me the following morning as I listened to an interview with Lester’s father. Until that point I’d resisted the cancer-survivor angle because Lester himself expressed a desire to move beyond it. But Lester’s father marveling about a no-hitter his son threw in high school conjured images of the star pitcher as a kid, the kind of pitcher who might have thrown three no-hitters in little league, just like Paul Mather. And Lester’s father saying that the only thing that mattered was that his son was healthy and cancer-free made me think of Paul Mather’s father, whose melancholy, seemingly overprotective presence provides the novel with an ominous tone long before the word cancer is ever mentioned. The most telling scene involving the father is the scene that I started describing above. In the end, Paul gives in to the temptation of the ball that feels so good in his hands. He starts pitching, just lobbing it at first, but soon he unleashes his entire awe-inspiring arsenal. He stops when his blazing pitches have made his catcher's hand red and swollen, but he’s on the brink of going even farther, of walking off with the boys to their game. His father stops him by calling his name and telling him to come back inside. But what’s telling about the scene is that his father, according to a feeling Paul gets, had “been standing there for some time watching.” He wants to protect his son, keep his son from hurting himself, yet he can see the joy his son is getting from playing the game he was made to play. Below is Paul himself describing that joy, from just after unleashing a breaking ball so nasty the catcher couldn’t handle it.

I first read the Hang Tough, Paul Mather when I was eight or nine years old. I’d read other baseball books before—in fact, other than Spiderman and Fantastic Four comics, baseball books were all that I ever read—but I hadn’t fallen in love with any of those books. Hang Tough, Paul Mather was the first. The story’s striking familiarity drew me in instantly. Like me, Paul Mather was one of two brothers. Like me, he was an outsider, part of a family that was new to their town. Like me, nothing was more important to Paul Mather than baseball. But the vital difference in our life stories was what drew me in even further. Here was a boy who lived for baseball who was having baseball taken away. The book was so important to me that after I lost the copy I had as a child I bought another copy somewhere. But some years after that, my aunt, an elementary school librarian a few towns away from the town where I grew up, found a book with my name in it in a pile of books the library was giving away. The favorite book of my childhood had found its way back to me. What was your favorite book as a child? Jeff Torborg

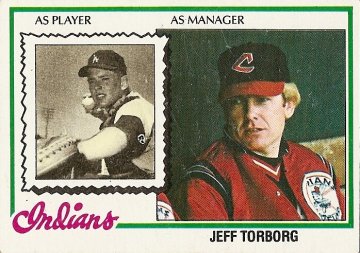

2008-05-20 06:25

How much does a catcher contribute to a pitcher’s success? There was an attempt to quantify the answer to this with a statistic called catcher ERA, but the numbers for catchers varied too much from year to year for the stat to be trusted as an accurate statistical tool. If anything, the statistic suggested that catchers are pretty much going along for the ride, and catcher ERAs merely mirror the relative merits of pitchers. If that’s the case, Jeff Torborg was a particularly lucky guy, but not as lucky as Jason Varitek, who last night surged ahead of Torborg and eleven other catchers to become the all-time leader in no-hitters caught. (As Gordon Edes points out, one of the other catchers with three no-hitters caught, Ray Schalk, was for many years credited with being a part of four no-hitters, but one of those was a game in which his pitcher lost his no-hit bid in extra innings; in 1991 such games were no longer considered no-hitters.) I was actually surprised to hear that there were so many catchers who had been a part of three no-hitters, since the first and only guy I think of when I think of multiple no-hitters caught is Jeff Torborg. This may be because of this card, which includes, on the back, Torborg’s tepid major league statistics (.214 lifetime batting average with 8 home runs in 1391 at bats) along with a couple lines of text at the bottom: "Jeff caught 3 no-hitters in his career . . . by Sandy Koufax (1965), Bill Singer (1970), and Nolan Ryan (1973)." I didn’t know much about Bill Singer, but I did know that there were no more impressive names from the pitching world than Nolan Ryan and Sandy Koufax, and Jeff Torborg had been on hand to collaborate with them at their most superhuman. Though this did rescue Torborg in my mind from total anonymity, I doubt I gave him much credit for his feat. All he had to do was catch immortal fastballs. I’m sure it's bias that makes me want to give Jason Varitek credit where I gave Jeff Torborg none. But bias aside, Varitek does have the list of names of the no-hitter pitchers he’s worked with (a fading Hideo Nomo, an erratic Derek Lowe, and two talented but very young pitchers in Clay Buchholz and Jon Lester) as a mark supporting the claim that he had something to do with their success. Also, throughout his career both pitchers and coaches have remarked at length about Varitek’s ability to positively influence pitching performance. Maybe everyone saying it has made it a fact. All I know is that as I sweated out the last few outs of the game last night I was glad the captain was behind the plate. As for Torborg, shown here at the beginning of his long and mostly featureless managerial career, I no longer think first of him as an extra in stories of no-hitter greatness. This changed for me around the time Ray Schalk was dumped back into the pile of three no-hitter catchers, in the early 1990s, when Torborg became the manager of the New York Mets. He ended up presiding over a colossal Mets failure that season, but what I remember most is the defining moment of his bright and hopeful first press conference. The phrase he uttered, about a newcomer to the team, came to loom over the ruin of the season like a curse. "Just wait'll you see Bill Pecota," Torborg proclaimed. Rookie Infielders

2008-05-19 06:59

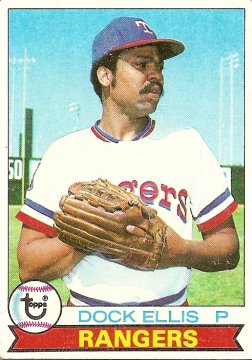

Yesterday at Fenway featured considerable fireworks from the two reigning rookies of the year, the A.L. award-winner Dustin Pedroia of the Red Sox going 3 for 5 with a home run while N.L. award-winner Ryan Braun pounded two home runs amid talk of his lucrative new contract. But neither of these players generated the excitement of the contender for this year’s award in the A.L., Jacoby Ellsbury. Everyone loves a rookie, but no one loves a rookie more than little kids, who see themselves in the young newcomers. I was just waking up to baseball in 1975, during perhaps the most celebrated season for rookies in major league history, when not just one but two members of the Red Sox burst into the everyday lineup and posted ridiculously good numbers while leading the Red Sox to the World Series. Jim Rice would have won the rookie of the year in most any other year, but his teammate Fred Lynn was even better, winning not only the Rookie of the Year award but also the league Most Valuable Player award. His numbers were indeed a bit better than Rice’s, but he also had a quality that made him the prototypical rookie—he seemed like an utter natural, as if he was born to play baseball. He could do everything—hit for high average and for power, run, throw, make breathtakingly spectacular catches in centerfield. By the year the above card came out, 1977, the gravity-defeating qualities of Fred Lynn’s rookie season had been undercut by a decent but unspectacular, injury-riddled 1976 season. Lynn would show signs of brilliance again, especially in a 1979 season that rivaled his rookie campaign, but for the most part his 1976 season proved to be the blueprint of his good but not great career. In 1977 I was still hoping for Lynn to once again become the Golden Boy, but the presence of the need to hope, which can’t exist without its flip side, doubt, was the beginning of the end of the dream of a career of pure flight. So my view on rookies in 1977 had matured beyond blind faith in limitless possibilities. Still, Fred Lynn and Jim Rice had taught me to be on the lookout for budding superstars, so I’m sure when I opened a new pack and found the card shown at the top of this page I tried immediately, hungrily, to identify the next vehicle for my vicarious dreams. And I’m also pretty sure that this attempt thunked dead in a nanosecond, as soon as my eyes were drawn to the upper lefthand corner of the card. I’m sure after I stared at Juan Bernhardt for a few seconds I pried my glance away from him and tried to muster some enthusiasm for the other players. But even if the ominous specter of Juan Bernhardt hadn’t been looming over everything else in the card I don’t think I would have been able to shepherd a dream of the brilliant rookie through an inspection of the other pictures on the card. In the lower left, Jim Gantner looks doughy and bored, as if he’s just watched the team bus leave without him and doesn’t really care. Beside him is the alarming image of a fabrication of paint identified as Bump Wills, whose frozen visage is somehow overshadowed by the frighteningly unreal backdrop, which suggests a world stripped of every living thing, every note of every song, every breath. The name and the boyish good looks of the player above Bump Wills offers some promise, but his awful brown and yellow Padres cap taints the dream, dragging the name Mike Champion down into the realm of sarcasm. Which brings things back to Juan Bernhardt, whose severe, deeply-lined face instantly tainted with irony the promise of the rookies card. Ethnicity aside, he looks old enough to be Mike Champion’s father. (For the record, the back of the card lists Juan Bernhardt as being born in 1953, which would make him 24 at the time of the picture, but it also lists his birthplace as being in the Dominican Republic, which has been known to produce players who are not always completely honest about their year of birth.) But more ominous than the sour, aged expression on Juan Bernhardt’s face is his black cap. I’m pretty sure I had never seen such a thing on a baseball card, and I’m pretty sure that it shook me up. I suppose, judging from the pinstripes still visible in Bernhardt’s uniform, that the Topps people only had an image of Bernhardt on the Yankees, and rather than going to the trouble of imposing a Mariners logo—which in 1977 was still a theoretical entity—they just smeared out the interlocking NY. But the result is so bleak and funereal that I think it may have harmed me in some barely perceptible but fundamental way. I was no longer a rookie. Dock Ellis

2008-05-18 12:43

Dock Ellis seemed to add an exclamation point to every moment he was ever involved in. I just wanted to take a moment on this Sunday afternoon to thank him for all those exclamation points, and to wish him the best. As reported in today's New York Post (link provided by Baseball Think Factory), Dock Ellis is in a situation his wife calls "a matter of life and death." Every so often, especially upon hearing somber, sobering news like that, I wonder why my life has come to center around the thin rectangular representations of baseball players from three decades ago. Sometimes I think it's a strange mid-life crisis. Sometimes I think I'm slowly, publicly losing my marbles. But maybe I just have a need to connect to a time that, thanks to Dock Ellis and all the others, felt as wild and weird as a Jimi Hendrix solo screaming though the acid-dazzled brain of an unhittable major-league pitcher. Woodie Fryman

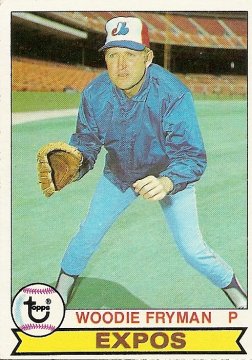

2008-05-16 08:29

Unless I’m forgetting something, always a distinct possibility, there is only one former major league city. I'm not counting the borough where I lived for many years, Brooklyn, which is a part of a larger city that from what I understand has major league baseball affiliation of some sort. Of course, the same can no longer be said about Montreal. Big league baseball has left other cities before, such as Baltimore, Milwaukee, Washington, and Seattle, but it always returned to those cities like a guy crawling back to an old girlfriend he’d once dumped. "It can be like it was, only better, I promise," the guy pleads, a heart-shaped box of candies in one arm, flowers in the other. This from the same guy who’d once explained that the relationship had grown stagnant and empty then packed up everything but some mildewed jockstraps and sped off to his sexy, sun-drenched new life without even turning back to wave. What the guy deserves is a kick in the nuts. But I’ve never heard of a city, even a formerly spurned city, saying no to major league baseball. It is pleasant to imagine Montreal being the first to refuse an attempt at reconciliation—I envision a torch-bearing mob, led by Warren Cromartie and a wine-breathed, filthy-furred Youppie, scalding the sweets-bearing representative of major league baseball with intricate Gallic curses as he flees across the border, head bleeding from a fresh hockey puck wound. But let's face it. Major league baseball will probably never return to Montreal, so the act of remembering is the only way for the Montreal Expos to endure. In that sense they are the most important team in the world of the Cardboard Gods, a world created solely to hold onto things as they fade. Because lately I keep finding baseball cards all over the place, I haven’t written about the cards from my disappearing childhood for weeks. Though I enjoyed the feeling that I was for the first time in a long time opening my eyes at least a little to the world of the present moment, I have also started feeling a little thin and empty without the ritualistic attempts to connect to my past. With my latest extended meditation of found baseball cards having run its course, I want to reach for an old card that will bring me back that feeling that what is gone can still have some kind of a life. I want to reach for a Montreal Expo. And so today’s prayer is to Woodie Fryman, who after over a decade of mostly anonymous toil for several teams, including an earlier stint with Montreal, finally found a niche as an effective left-handed reliever for the excellent Carter-Dawson-era Expos. He looks in this picture to be someone who would know how to handle a crisis, like a former small-town farmer whose unflappability and natural moral uprightness inspired his townfolk to elect him (though he hadn’t campaigned) to the office of town sheriff, where his keen eye and steady hand allowed him to steer the town through whatever troubles came its way. In fact he looks in this photo as if he may already be in the middle of a crisis. Perhaps a young Ellis Valentine, suffering from a premonition of the beanball that would derail his promising career, has begun raving and screaming and wildly swinging a bat around. While the Rodney Scotts and Scott Sandersons of the world bolt for safety, Woodie Fryman bravely, if also with wise caution, approaches the unstrung rightfielder and attempts to talk him down. "Whoa there, big fella," he seems to have just said, his voice a drawling, mellow tenor, like that of a bluegrass great. "Easy now. Take ’er easy." He is fully prepared all at the same time to continue calming his teammate, to use his glove hand to fend off a lunge from his teammate, or to save another teammate from an attack by taking the hulking maniac down with a skillful leg tackle. It’s natural that I, a panicky coward, would be drawn to such a card, or drawn, more accurately, to embroider this card with such a fiction. But in fact what first drew me to this card was not a need to imagine myself out of myself and into a more sturdy, capable persona, but the more primal need to be protected by such sturdiness. In other words, if I’m imagining myself into this card, I’m not imagining myself as Woodie Fryman but as the unhinged lunatic Woodie Fryman is prepared to help. In my madness I want to escape the moment, to crash through to oblivion, but if I make a run for the empty seats and artificial turf beyond Woodie Fryman, for the oblivion of the Expos as they are now without the mercy of memory, Woodie Fryman will intercede. He'll use words, and if they don't work he’ll drop me with a left cross to the chin or floor me with a shoulder to the solar plexus. One way or another, he'll stop me from disappearing. Kevin Millar

2008-05-14 08:46

When I first found these ripped up 2008 cards on Golf Road I envisioned spreading the lucky, hopeful buzz the find gave me over an entire month, writing nearly every day about one of the cards, welcoming the spring by celebrating the miraculous renewal of each trashed present-day journeyman, a month-long 22-chapter novella that would ultimately establish the bus stop on Golf Road as my personal church, a temple for the embrace of the moment in the heart of the blind spot of the American Dream, which also happened to be the heart of my own strongest desire to escape the moment. It was pretty ambitious. It was bound to end up incomplete. In truth there’s not much to the story. The bus came by and I got on. That about wraps things up regarding the day I found the cards. There’s also a Grateful Dead song that starts with those words. The bus mentioned in the song is metaphorical in some ways, but the metaphor has its roots in an actual bus, Furthur, which belonged to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, who used the vehicle, an old conveyance for schoolchildren that the proto-hippies had emblazoned with Day-Glo paint, to roam the land ingesting prodigious amounts of LSD and acting unusually around members of the general populace. This was in 1964. They believed they could transform society by passing along, through artful pranks, the enlightenment they were experiencing. Mostly they exhibited their painted naked bodies and yelled at tax-paying citizens with a megaphone. When they returned to California from the cross-country trip they began inviting the general public to acid tests, which the Grateful Dead fully participated in, managing somehow to play their electrified instruments and add strange music to the general sensory assault while they, like everyone else there, hallucinated ferociously. In other words, the bus came by and they got on. Others followed. The man who would become my step-father was the first in my family to get on the bus, dropping out of college, growing his hair long, crisscrossing the country on a motorcycle, eventually stumbling around the Oregon woods on acid made by the Merry Prankster’s own famous chemist, Owsley. My mother followed him onto the bus. In fact they literally met on a bus to a peace march. I don’t know if you could say my father ever got on the bus, but he didn’t throw rocks at the bus or anything, and when the family split up he did ride another kind of bus (Greyhound) up to see us a lot, and my brother and I took the same Greyhound down to see him every summer. A few years later I rode a Greyhound all the way across the country. There was Cowboy Neal at the wheel. That’s another line from the Grateful Dead song. It’s a reference to Neal Cassady, who was the driver of the Merry Prankster bus and who I first read about in On the Road a couple years before my cross-country bus ride. I wanted to ride beside him, crisscrossing the country in a frenzied search for ecstatic visions, so I tried to get on the bus, but it was a Greyhound. Once the Greyhound had taken me and my liquefying spine to California I saw my first Grateful Dead show and started tripping pretty hard during the first notes of the first song the visibly aging men on stage were playing, Jack Straw. We can share the women we can share the wine. There were people sharing things all around me, most notably hugs in big unshowered hug circles. I found I wanted no part of it. It wasn’t all the hairy armpits, either. I’ve never been a joiner. I prefer solitary, even lonely, anonymity, where without ever having to actually talk to anybody I can painlessly imagine great untroubled renown and warm feelings of vibrant community. I went to a few more Grateful Dead shows over the next couple years and it was the same thing: strangers stopping strangers just to shake their hands, as another of their songs go, and me off to the side, my jaw clenching and my nostrils flaring with the chemical pulse coursing through me, my pupils like fire-blackened dimes. At one show a hippie girl even shouted at me, in a rhetorical way that was akin to a distancing shove of the palm to the chest, “Why are you hiding?” Anyway that was all a long time ago. More recently the bus came by, the Pace Bus, and I got on and slid my transit card into the slot. That’s about it. Cowboy Neal wasn’t at the wheel but it turned out that Kevin “Cowboy Up” Millar was partially and in pieces in my pocket. Quite a while later the bus arrived at the CTA terminal and I got off. I got on a train. I got off the train. I walked home. Same as any other day. Today I heard on the radio that there’s a physiological phenomenon called synaptic rutting, which leads to physical and mental degeneration and which stems from the kind of repetitive living that I engage in. But I guess there are always slight variations in my routine. On the day in question, of course, I was able on my arrival at my apartment to delay the routine of simultaneous ingestion of food and television by dumping my card shreds onto the counter and with the help of my wife piecing together whatever we could. When she went to take a shower I taped up the pieces, trying to be careful at first but then deciding to be willfully haphazard, so that the torn parts showed even in the cards that had all their parts. Not all the cards had all their parts, and I guess it says something about me that these partial cards are my favorites. Of those favorites, this Kevin Millar card is first and foremost. This is not surprising, given my favorite team, and given that the player featured on the card not only started what turned out to be the greatest rally in team history but also seemed to be the foremost contributor to the 2004 Red Sox’ renowned looseness. He was, and probably still is, a goofball. Before Millar the Red Sox had always stared into their chronic collapses with the Yaz-faced dourness of a man being told there was no cure for his hemorrhoids. Conversely, Millar’s response to the deeply humiliating 0-3 hole the Red Sox dug for themselves in the 2004 playoffs was to smile like he had just stumbled from a keg party and tell reporters that his team was going to shock the world. He didn’t sound like the raving young Cassius Clay, the first to make such a claim, but rather like a guy who was simply prepared to continue having some fun playing baseball. How much Millar’s attitude and locker room hijinx actually contributed to the team’s famous comeback is a matter for debate, but the fact is the team seemed to take his lead and play the game both without tension and with passion, a sure sign that they were, as any goofball would have wanted it, enjoying themselves. I was just thinking last night that the goofball is a lucky guy. Last night as he played first base for the Baltimore Orioles a run scored when he let a groundball go through his legs. He has managed to put together a good career, but what would have happened if that error had not occurred in the first inning of an early-season game that his team would come back to win but instead had occurred in, say, the tenth inning of the sixth game of a World Series? But then again maybe there’s something to being a goofball. Maybe goofballs are just luckier. Maybe they know that the mere fact of being alive is itself a pretty lucky thing, so you might as well enjoy yourself when you can. I was lucky to find these cards, especially the partial 2008 Kevin Millar. In the days following my find I continued to search the grass around the bus stop on Golf Road. I didn’t find anything the first time I did this, but on the second day I came up with three scraps, one of them the missing piece of Kevin Millar. I put them in my back pocket when the bus arrived. Later, as I was exiting the train station in my neighborhood, a guy was handing out brochures for some street fair. I avoid interpersonal contact whenever possible, but because of one of the briefest chapters in the spotty employment history that has brought me to Golf Road I now take things from people when they hand them out. Several years ago I got some money by working for an outfit that handed out surveys in front of movie theaters. We had to say the same thing over and over: “The producers would love to hear what you think of this movie.” The repetitiveness of this, and the fact that I had to go against my deep-seated personal preference to leave people alone, made me start crying on the subway home. But my money was so thin I had to do it again a few more times. Most people I accosted passed me by. During the movie we filled in blank surveys with fictional responses to the movie we hadn’t seen, then when the movie let out we went up and down the aisles and pried any castoff surveys loose from the gooey floor. So anyway I always take pity on poor slobs handing out things, which led to me taking the brochure and shoving it in my back pocket, then pulling it out when I came to a garbage can. When I got home I found that I only had two scraps of cards in my back pocket. The final piece of Kevin Millar had been jarred loose somehow, probably by a ripple from my lackluster, ridiculous past. I was angry at first, but what are you gonna do? Punch yourself in the head? Fuck it, life is short. You might as well celebrate what luck comes to you and leave the rest for someone else to find. Tim Redding

2008-05-12 13:33

Today I'm not going to the actual Golf Road, because today is the day of the week that I have arranged to be my big writing day, my day where I better be brilliant because I'm sacrificing a day’s pay to get it. In effect I am paying money I could really use just to have this day. Earlier I punched myself in the head as I screamed obscenities. I was trying to write. My head is OK now but my throat is still a little raw. After that I stuffed food down my throat and took a shallow, awful nap. This day away from Golf Road has turned into Golf Road. I am nowhere, waiting for something that will never come. I feel like ripping a notebook in half or shredding some baseball cards. But I already did something like that a long time ago and it didn’t make any difference. I was trying and failing to write, just like right now. I was twenty years old and had filled up a few notebooks by then. I knew I didn’t know how to do anything and was scared of everything and so my only way out was to write, but I couldn’t. I gathered up all my notebooks and threw them in a dumpster. I felt OK for a moment, lighter, but in the end nothing changed. I started the whole process all over by opening a new notebook and writing a shitty poem, then I spent the rest of the day eating chocolate chip cookies and putting golf balls at a table leg. Most days I'm waiting in a place no one wants to know, least of all me. Golf Road. That moment, that long moment in the polluted dusk, waiting, the day chewed. How many days do you get? Stranded on Golf Road. A whole life leading to it. Things you could have done differently. But you didn't. Anyway the past is gone. It doesn't exist. You find some ripped pieces. You have lived such a life that you happen to recognize that these pieces go together. You don't know much else but you know this. You gather them up and take them home. You tape the pieces together and add them to the pile. Next day you search for more pieces. You find a couple. The day after that you don't find any. You keep looking every day for more but that chapter is over and you're back where you started, nothing to gather, nothing to rescue, nothing to hold in your hands. (to be continued) Byung-Hyun Kim

2008-05-08 09:05

Golf Road There wasn’t a lot to do in my town. You waited for winter to end. When spring came you walked half a mile down Route 14 to the general store to buy a couple packs of baseball cards. A few days later you did it again. The years went by. I stopped buying baseball cards. Instead, I extended my walk just beyond the general store, to the road that branched off Route 14 and led up out of the valley. My brother had showed me what to do. You stand there and when a car comes along you stick out your thumb. Maybe they stop, probably not. Very few cars come along. * * * In 2003, I found myself getting excited when the Red Sox picked up Byung-Hyun Kim. He’d authored two horrific collapses in the 2001 World Series. Few if any players had ever failed as spectacularly or as publicly as he had. In the moments after that double-collapse, he’d seemed broken, a ghost of a man. But the following year he’d bounced back to save 36 games, with 92 strikeouts in 84 innings. And he was still only 24. Most of all, he still threw a hundred miles an hour. I tried to ignore the image of the ghost of a man and focused on imagining Byung-Hyun Kim to be exactly what my favorite team had always lacked. In this life you learn to gnaw on the spent, faintly narcotic cud of hope. Sometimes it numbs the pain of waiting. * * * Once, while I waited for a ride up out of my town, a pickup truck turned off of Route 14 and zoomed past my upraised thumb. “Get a car!” the driver yelled. As the pickup disappeared the horn sounded. Like the General Lee, it had been rigged to play Dixie. I’ve never really put that moment behind me. * * * Kim had switched to the starting rotation at the beginning of 2003 with Arizona, and for his first month with the Red Sox he remained a starter, but in July he moved into the closer’s role, which had been Boston’s biggest weakness that year. In fact, it had been Boston’s biggest weakness for most of their existence, ineptitude in that area a perfect Schiraldi-faced symbol of their long history of repeatedly getting close to winning it all only to blow it at the end. In half a season as the closer, Kim saved 16 games, but he started looking shaky near the end of the season. His shoulder was bothering him, but his inability to get the ball over the plate seemed to the fans, and to his manager (who started yanking him at the first sign of trouble), to be signs of cowardice, the pressure of the looming postseason causing him to wilt. In his one brief appearance in the playoffs, at a game in Oakland, his ineffectiveness contributed to a Red Sox loss. The next game, back in Boston, the fans showed their disappointment during pregame introductions. It wasn’t fair, but it seemed to the fans that a guy who could throw harder than all but a few human beings who ever lived didn’t have the stomach to throw strikes. So the boos rained down on the 24-year-old far from his home. What would you have done in that moment if you were him? * * * I wait on Golf Road, holding the damaged nest of baseball cards against to my chest. Minutes ago what was trash is now the newest addition to my most prized possession. Cars fly by. There’s always a small part of me braced for one of the drivers to yell something at me, to mock me for being carless. For once I don’t care. I found a bunch of ripped baseball cards. I feel rich. I feel lucky. If anybody said anything I’d just laugh. But the problem is that on Golf Road nobody says anything. The sound of traffic is like the roar of some foreign tongue you'll never be able to learn. Even so, the message is clear: You don't belong. You’ll never belong. (to be continued) Brad Ausmus

2008-05-05 15:03

Golf Road I lurched around grabbing up all the shreds I could find. After reading the name on the first piece I’d noticed—Brad Ausmus—I didn’t waste any more time looking at names. I just wanted to gather up everything I could before the bus came. The pieces were light and jagged. They weren’t weather-beaten, but they were slightly curled, like old photographs. They were distributed over a fairly wide area, implying that they had either been tossed up into a breeze, like confetti, or had been moved more gradually by intermittent gusts after having been flung down. Either way, the lack of any further weather-related markings or discoloration made it seem likely that the cards had been abandoned just a few hours before my arrival on the scene. As I gathered the fragments I noticed that they were physically different from the baseball cards from my childhood. The material seemed cheaper, flimsier, sharper-edged. They surely were easier to rip into pieces than a similar stack of cards from the 1970s would have been. It probably felt good, at least for a second, to shred them. To so easily say I don't need you. * * * The first and third jobs I ever had were at East Dennis Shell, on the inside part of Cape Cod’s elbow. My second job, before I begged to pump gas again, was with a Greenpeace office based in Hyannis that sent me and other young people all over the Cape to knock on doors and ask for money. At one house a balding Jehovah’s Witness waved off my environmentalist spiel and lectured me at length about how the world was going to end soon. "There’s nothing you can do to stop it," he said. On another day a middle-aged woman in a gray nightgown stared past me and spoke of all the cars going and going, always, all the time, just going and going everywhere. After repeating this assertion for a while she finally leveled her watery gaze at me. "Where are they all going?" she asked. * * * When I was done gathering, I stood at the edge of the bus stop shelter. I held the small mass of ripped cards to my chest lightly, as if I was protecting a storm-damaged bird’s nest. The traffic of Golf Road flew by. People aren’t really meant to witness that kind of traffic so closely. If you ever do, you’ll sense a meanness in it. Everyone wants to get to what they imagine is their real life. Everyone wants to get through the places that are neither here nor there. Everyone roars past in a blur. Everything they roar past is a blur. This place is no place. This moment is no moment. * * * Where are they all going? Where is America? If you listen to the patriotic songs it’s in a brave battle for freedom and in God-blessed natural beauty and bounty. The prevailing cultural mythology of America extends these themes into a vision of a promised land of individual conquest and celebration. The American tames the wilderness. The American goes from rags to riches in the vibrant city. The American mows a flawless lawn behind the white picket fence of an alarm-secured suburban home. The American swats a home run in the bottom of the ninth to loose the democratic yawp of the masses across the sun-splashed green. * * * I could not field a very good team with the 22 players featured in the torn cards from Golf Road. Like many of the cards themselves, the roster has glaring holes, as there are no outfielders, no shortstops, and just one first baseman. Most of all: there are no stars. Brad Ausmus, the aging, light-hitting catcher, is probably the most well-known player in the pile. * * * Nowhere in the collective dream of America is there a pedestrian blurred into invisibility on a four-lane road, cars flying past in both directions, a drab brown nature preserve on one side, a string of bland corporate office buildings on the other, a cluster of chain restaurants off on one flat horizon, the opposite horizon dominated by the concrete overpass of an Interstate highway, traffic so thick it barely moves. There’s no store anywhere around. He must have bought the cards at some earlier time, looked at them, brought them along with him to his job, put in a day’s work in a cubicle, and looked at them again to try to fight the monotony and meaninglessness of the moment that is not a moment. He must have leafed through the cards looking for meaning in them, looking for some connection to that persistent American dream of triumph. Looking for a star. Looking for somebody. Nobody, nobody, nobody, is what he heard as a reply, in the cars flying past, in the faces of the cards in his hands, in the life he was leading, in the absence of the gods. It must have felt good, at least for a second, to tear all the slick bright nobodies to shreds. Brandon McCarthy

2008-05-02 09:22

Golf Road Sunday I found a Steve Howe card in the mud. Monday, I wrote about it, and while I was doing so I discovered that it was the second anniversary of Steve Howe's death. The coincidence made me wonder if I was part of some wider, unfathomable plan. Maybe there's something beyond the self. Maybe there's a wholeness surrounding all our ripped, scattered pieces. I don't know. Tuesday I went to work. It takes quite a while to get there. A long walk up Western Avenue, a wait, a train, another wait, a bus, then a short walk to the corporate complex from where the bus lets me off on Golf Road. I work all day in a cubicle in a large room full of cubicles. I'd say the hours pass slowly, but that's not quite accurate. I try to do a good job, and I guess I do OK; four years now and they haven't sent me packing. But even so there's a part of me that I learned a long time ago to tear off and toss aside on the days I punch a clock. I remember my first job, pumping gas at a Shell station on Cape Cod. There the hours passed slowly, tortuously. I hadn’t learned how to leave pieces of myself behind. That was over twenty years ago. I’ve gotten much better at it since then. So on Tuesday the hours passed. At quitting time I shut off my computer and bolted for the door. I hustled across the parking lot and through the pack of lazy, malevolent geese that use the wide corporate lawn as their toilet, then I came to a stop at Golf Road. It can take several minutes to cross the four lanes of heavy traffic; many times I've been waiting for my chance to cross while my bus flew past in the farthest lane. Sometimes there are brief gaps in the traffic in the two lanes closest to me, but there are usually cars backed up on a smaller road just to my left, waiting at the long light to turn onto Golf, so any attempt on my part to make a dash to the center median would end with me getting shoveled up onto the hood of a car making a white-knuckled right on red. But on Tuesday I was lucky. There was both a small gap and an unusual lack of cars stopped at the light, so I scuttled like a light-startled cockroach to the thin strip of concrete separating the eastbound and westbound lanes. You have to stand straight and suck in your gut on this median or risk getting disemboweled by a speeding sideview mirror. While on this median I always find myself thinking about all the many times I've let my mind wander while driving, the car drifting beyond the margins of the road. I got lucky again with a second gap and scurried the rest of the way. Sometimes there's someone already at the bus stop. There are no buildings on that side of the road, just a drab, flat nature reserve patronized solely by car-drivers with bikes, so if there's another person waiting for a bus he or she had to do what you just did to get there, and upon your arrival the two of you exchange the sheepish glances of the hunted. But on Tuesday I was able to enjoy in solitude my small, lucky feeling of getting across Golf Road without dying or, worse, watching the bus go by without me. I wonder if moments like these ever make it into the court proceedings in the mind of the suicide ponderer. Does the underpaid court-appointed public defender of Life ever rush disheveled in his cheap tan suit through the courtroom doors amid speeches of terrible eloquence by the dark-garbed Prosecutor on cancelled dreams and loveless nights and hopeless endless afternoons to yell "Hey, wait"--his voice cracking--"don't you remember that time you made it through the subway doors just as they closed? Or the time you got change for a ten when you used a five? Or the time when the freezing drizzle allowed you to move down to the good seats for once in your life, so close you heard the sound of a guy sliding into third?" Well, I don't know if these little flickers of light ever make it into the internal To Be or Not To Be conversation. I've fantasized as much as the next guy about how my death would cause millions of beautiful women to weep, but for all my chronic gloominess I've never really stared down that awful corridor. All I know is that life is pretty much a losing proposition, so it stands to reason you should celebrate the rare victories, however small. And so on Tuesday I had that tiny extra lift of getting across Golf Road quicker than usual and without missing a bus. I have to think this lift allowed me to look twice at one of the many pieces of trash littering the fume-sickened grass around the bus stop. Most of the time I walk through the world blindly, objects appearing before me without ever registering. But I was feeling lucky, lucky to be at the bus stop, which is not that different, really, from feeling lucky to be alive. So I was able to notice that the piece of trash had somehow, distantly, signaled to some part of my brain that it was not just a piece of trash. And it wasn't. It was half of a baseball card. I picked it up. For the first time in all the days I've spent waiting at that bus stop I studied the ground all around me. There was another ripped piece of a baseball card a few feet away, and beyond that another, and beyond that another. There were ripped pieces of baseball cards everywhere. (to be continued) |