|

Monthly archives: January 2008

Bob Jones

2008-01-30 08:00

Born in the USA (continued from Garry Maddox, 1975) I. “Actually, I’m looking forward to it,” he said. I think he’d been working out a little, doing some pushups. I’d never met him before, and my wife hadn’t seen him since he was a little boy. He was polite and soft-spoken, a really nice kid. “He’s so sweet,” my wife said. A few months later we saw him again at a big family reunion picnic. He had just gotten out of basic training and was in uniform, on a brief home leave before going to advanced training and then Iraq. He stood ramrod straight the entire time, several hours, the most incredible display of good posture I’ve ever seen. He also seemed a little jumpy. My wife recalls that when she said hello to him he flinched. The main activity of the picnic, besides eating and talking and drinking beer, was a tournament involving a horseshoes-like game in which a beanbag was tossed underhand at a small hole in a low triangular wedge of wood on the ground. You may know the game, which is referred to by different names but which is most commonly referred to, believe it or not, as cornhole. Members of the picnic paired off and played other pairs in elimination games. An early match pitted my wife and me against my wife’s cousin and his younger sister. “How was basic training?” I asked. The two of us stood by one of the wooden cornholes and took turns tossing beanbags at the other cornhole, where his sister and my wife were standing. “Hated it,” he said. He didn’t say much else except to occasionally try to fire insults back at another cousin of my wife’s who had been in the Navy a few years earlier and who was slouching nearby, beer in hand, and languidly razzing my opponent for being a Marine. The few rejoinders that the eighteen-year-old could muster were hesitant, clawless. Meanwhile, his cornhole tosses got worse and worse. You have to kind of toss the thing in a soft arc to land it on the wooden wedge and get points, but as the game neared its conclusion my wife’s cousin’s throws kept getting lower and harder, the beanbag ricocheting off the wood and landing in the grass beyond. I don’t know anything about war or soldiering, but I know quite a lot about unraveling during a sporting contest, and it seemed to me that the young Marine was wilting in the pressure of a family picnic game of cornhole. I didn’t get an inkling of what he might have actually been going through that day until just a few days ago, when I was reading Denis Johnson's 2007 novel Tree of Smoke. The novel is about the Vietnam War. One of the characters, James Houston, decides at the age of seventeen with nothing else on the horizon that he might as well follow his older brother into the armed services. The first passage below describes his experience at basic training. The second describes him being home on leave just after basic training. The first two weeks of basic training at Fort Jackson in South Carolina were the longest he’d experienced. Each day seemed a life entire in itself, lived in uncertainty, abasement, confusion, fatigue. These gave way to an overriding state of terror as the notions of killing and being killed began to fill his thoughts. He felt all right in the field, in the ranks, on the course with the others, yelling like monsters, bayoneting straw men. Off alone he could hardly see straight, thanks to this fear. (pp. 139-140) II. Just about all I know about the next year is what I learned over thirty years ago when I first turned over the 1977 card at the top of this page, that in 1970 Bob Jones was “In Military Service.” I’d seen the terse line before on other cards, such Garry Maddox’s 1975 card, but only very occasionally, so it was rare enough to send a chill through me. One of the things that I loved so much about the Cardboard Gods was their invulnerable clarity. The statistics on the back of each card told you where each player had been and what each player had done, the place names and numbers in solid black ink, inarguable. Some numbers told a story of a player who was rising, others told a story of a player who was falling, but the key thing was that all of them told a story. Everywhere else was ambiguity, and where there was ambiguity there was the possibility of diminishment, change, loss, pain. In the numbers there was no ambiguity, but instead a clarity that allowed me to imagine a haven of invulnerability. I dissolved into this haven, leaving all dangers behind. But there’s really no perfect safety anywhere. Even the numbers on the backs of the Cardboard Gods can be interrupted. On Bob Jones’ card for 1970 there is no place name and no numbers, just that phrase. In Military Service. Where was he? What numbers was he compiling? Where they good numbers or bad numbers? Was he rising or falling? Was he safe? According to baseball-reference.com, Bob Jones “served in Vietnam from August, 1969 to February, 1971 and became deaf in one ear as the result of a combat injury.” I didn’t know that when I looked at this card as a kid. All I knew was that he’d had a gap in his pro baseball career, that he’d come back and had starting slowly rising, hitting .321 at Anderson in 1971, driving in 91 runs in Spokane in 1974, hitting .355 at Sacramento in 1976, that last lofty number leading to his first extended stay in the majors after two brief cups of coffee with the Rangers: 78 games with the 1976 California Angels, enough to gain him entry into the realm of the Cardboard Gods. But on the front of Bob Jones' first-ever baseball card there seems to be no acknowledgment of his triumphant arrival. There is instead the hint of some other story that will remain obscure. Bob Jones knows the story. Bob Jones looks right through me. III. I don’t know what my wife’s cousin is going through. At the end of the picnic I had the urge to tell him something. I didn’t want to say good luck. As a follower of the gospel of Holden Caulfield (“I'm pretty sure he yelled ‘Good luck!’ at me. I hope not. I hope to hell not. I'd never yell ‘Good luck!’ at anybody. It sounds terrible, when you think about it.”), I try never to tell anyone good luck. I didn’t have anything patriotic to say, either. I was born in the U.S.A., but though I’ve occasionally had my moments of patriotism—such as the day Jim Craig draped himself in a flag and looked through the Lake Placid crowd for his father, and such as the day I returned from spending several months in post-Tiananmen-Square-Crackdown China (that day I got wet-eyed, I swear to the God that blesses America, when I came through customs and saw a flag-backgrounded portrait of President George H.W. Bush), and such as the period a little over six years ago when I spent a few months wearing a small American flag pin over my heart—I’ve generally shied away from waving the flag, mainly out of a fear that by waving the flag I’d be participating in some kind of a sanctioning prelude to a beating. I didn’t understand why there was a war going on in Iraq. I still don’t. A recent study found that the entry of the United States into the war was facilitated by a long string of lies. There were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. There was no link to Al-Qaeda in Iraq. There was no clear reason for us to be in Iraq. Yet my wife’s eighteen-year-old cousin was going to Iraq. So I'm standing there at the end of the picnic, everyone saying their goodbyes, and I want to tell him that I'm grateful that he's willing to make such a brave sacrifice, even though I don't understand the need for the sacrifice. More than that, I want him to be safe. “Take care of yourself,” is the best I can muster. His reaction is like that of someone with damaged hearing. That is, he doesn't react. He's someplace I know nothing about. As we shake hands, he looks right through me. (to be continued) Garry Maddox, 1975

2008-01-28 15:56

Chapter One I. On February 27, news anchor Walter Cronkite, so widely respected that he was considered to have the ear of the entire nation, summed up his thoughts on his recent trip to Vietnam. To that point Cronkite had passed along without any notable editorial comment the assurances of military leaders and policy makers that there was "light at the end of the tunnel," that the Vietnam War would soon come to a satisfactory end, yet another win for the Red, White, and Blue. Cronkite’s trip to Vietnam had been prompted by the recent Tet Offensive, a massive widespread attack by North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong forces on South Vietnamese and American targets. The gigantic surge revealed that the enemy was far from teetering on the brink of defeat. They could throw a lot at us and still keep coming. They weren’t going to quit. So if they weren’t going to quit, who was? "To say that we are mired in stalemate," Cronkite concluded, "seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations. But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could." II. When I was assigned to Charlie Company I knew there was something wrong. You could see it and smell it. . . . There was no sense of community, no sense of duty or responsibility, no sense of pride. . . . Anybody who says these guys were typical doesn’t know what they are talking about. . . . They were just a bunch of street thugs doing whatever they wanted to do. It was a group that was leaderless, directionless, armed to the teeth, and making up their own rules out there, deciding that the epitome of courage and manhood was going out and killing a bunch of people. On March 15, 1968, according to Bernhardt, a combination briefing and memorial service for fallen comrades had turned into a "pep talk that was inflammatory" delivered by Captain Ed Medina, who had made clear to everyone that "it was payback time, that we were going to get revenge for the terrible things they were doing to us. . . ." The next day, Charlie Company entered My Lai-4, a subhamlet of Son My, and killed almost everything in their path. A cover-up kept the massacre out of the public eye for nearly two years, but eventually three mass graves were uncovered that contained the corpses of five hundred villagers, including women, children, and the elderly. Even more lives would have been claimed had the three-man crew of an OH-23 helicopter not intervened, an act which, thirty years after the fact, gained them all the Solder’s Medal for Gallantry. The account of one of these men, Larry Colburn, is also given in Appy’s oral history. "I’ve seen the list of dead," Colburn recalls, "and there were a hundred and twenty some humans under the age of five." III. We the People might not have lost yet, but we sure as hell weren’t winning. We the People weren’t even a We anymore. IV. (to be continued) Brian Downing

2008-01-24 10:07

Adjunct! Wrap Party (continued, sort of, from Ron Schueler (4)) When I obtained this 1978 card I was 10 years old and as extroverted as I’d ever be. The world was small and warm most of the time, a roaming comfort zone of home and the hippie classroom that I’d been in for a few years and, of course, the little league field, and in that comfort zone I was a chatterbox and a joiner and a doer, all elements of my personality that fell away in years to come as I gradually donned the ashen costume of the apprehensive cipher. At home my brother and I talked so much about baseball that the weary adults of the house eventually decreed a moratorium on all baseball talk at the dinner table; I also talked so much in general that my sometime baseball-talking partner, as he edged into the silence-filled vales of puberty, had to institute his own unofficial policy of threatening glares and occasional arm-punches to get me to shut up. At school I was either talking with my friends or making (no doubt tiresome and unfunny) wisecracks to the teacher or plunging into projects like co-writing and directing a theatrical sequel to Star Wars that we put on for our classmates (I played Darth Vader and got to kill off Princess Leia) or overseeing (or at least pretending to oversee) the staging for a general public audience of the Broadway musical You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown. The small local paper, which was run by my aunt’s brother Dickie, even published a small write-up about me on the eve of the latter performance. It was a short paragraph in the back pages, wedged in between local notes relating that some village octogenarian or other was recently visited by relatives. I don’t remember the content of the article but recall that it mentioned that I was 10 in the context of a general appreciation for all I was accomplishing at such a young age. Here was a kid bound for big things! It was all sort of downhill from there. I peaked at 10. The slide from that peak may have begun with the performance itself, which must have been an excruciating, incomprehensible mess to watch. I had hacked the script to bits for a couple ridiculous reasons. First, because I didn’t know how to sing and didn’t like to sing, I got rid of all the songs, just deleted them. A musical without music! Then, upon realizing that no one was going to be able to remember all their lines, I chopped off the entire second half of the play. I guess we stumbled through a few musicless scenes and at the abrupt, inconclusive end all the surely bewildered parents in folding chairs applauded, but the whole experience left me feeling a little shaky. Apprehensive. Like maybe center stage wasn’t the greatest place to be. I got glasses around that time, big girly-framed plastic jobs that combined with my unruly long curly hair and weakling body to make me a pretty easy target of scorn outside my comfort zones, such as when I walked to the general store to buy baseball cards. I tried in such situations to be as invisible as possible. As the years went by my courting of invisibility increased as all my comfort zones eroded. At home my parents were no longer around much, letting go of their dreams of back-to-the-land self-sufficiency to take regular (and poverty-averting) jobs, and my brother became less and less willing to waste his time with me; and the hippie school tossed me out of its embrace and into regular junior high; and little league ended. The year after little league, I took a small part in the 8th grade play. Maybe I was casting around for something to fill the void. Maybe I was trying to reconnect with my former, outgoing, happier self. The terror I felt in the hours leading up to the one and only performance of that play were extremely intense, and when the play was over the euphoria I felt was only that I wouldn’t have to go through such an ordeal again, which I didn’t. From that point on, I avoided situations whenever possible in which I would be center stage. The one aberration in this lifelong policy was during the two years when I was an adjunct professor. The terror and dread that preceded every class never really abated during that time, and since then, I haven’t tried to teach again, even though it was, at least sporadically, the most meaningful job I ever had. Surely part of the reason I haven’t is that being in any kind of spotlight scares me. And now I wonder if I’ve grown addicted to invisibility, to retreat. So I turn today to Brian Downing for a little help. Here he is, in his tinted aviator shades and mesh, the same partially obscured Brut billboard in the background that was in the background of Ron Schueler’s card. Even though the viewer of both cards would assume from the identical backdrop and team name on the cap that Brian Downing and Ron Schueler shared the same moment with a Topps photographer, the two were never teammates. While newly acquired White Sox pitcher Ron Schueler was wrapping up the last two years of his career as a roaming adjunct, Brian Downing, now of the California Angels, was beginning to shuck off the costume of invisibility that had cloaked him throughout his years with the White Sox. It happened gradually. In 1978 he seemed the same innocuous weak-armed part-time backstop he’d always been, then in 1979 he batted .326 and made the all-star team, which seemed like a once in a lifetime aberration over the next two seasons, during which he hit .258 with 11 home runs. And then, suddenly, a whole new guy. I’m wary of inadvertently copying the great writing Bill James did on this very subject in his New Historical Abstract, but it’s sort of hard to tell the Brian Downing story without marveling Jameslike at the way Brian Downing suddenly transformed himself from the marginal regular-looking guy seen in the card at the top of the page into a bulging specimen worthy of the nickname listed for him on his page at baseball-reference.com, “The Incredible Hulk.” Anyone looking at his 1978 card and at the stats on the back of the card would have predicted that he’d have vanished from the league by the early 1980s, but instead he spent the entire decade swatting home runs (20 or so every year) and clogging the bases by virtue of his good batting average and ability to both draw walks and get hit by numerous pitches, the latter feat somehow a defining trait in that each of the errant throws, at least in memory, seemed to bounce impotently off his muscle-bound frame like punches off a brick wall. I think the famous turnaround has been the subject of scrutiny in recent times, these days when nobody can grow a muscle or hit a home run without raising suspicion. But I’m going to leave all that aside and not only give Brian Downing the benefit of the doubt but turn to him, as I turn to all these cards, for strength. In this life song gives way to song unless you edit the songs out, and weakness gives way to weakness unless you find a way to draw on strength from somewhere. I think now of one particularly desperate point in The Catcher in the Rye, when Holden Caulfield is crossing a street in the city and he starts convincing himself that he’s going to disappear before he reaches the other side. He calls out in his mind to his dead younger brother, Allie, the one who used to write poems all over his baseball glove so he’d have something to read in the outfield between pitches. Allie, don’t let me disappear. Allie, don’t let me disappear. Ron Schueler (4)

2008-01-22 10:47

Adjunct! Act IV (continued from Ron Schueler (3)) I first started writing about my baseball cards years ago, as my time as an adjunct was coming to a close. My teaching in those last few months had dwindled from a couple classes per semester to a single one-on-one tutorial with a pale, sunken-eyed Vietnam War veteran suffering from acute insomnia stemming from post-traumatic stress disorder. By then I’d run out of money and had begun racking up credit card debt to pay for essentials. I’d been spending the year living in a drafty cabin in the woods with no electricity and no running water and a small leaky woodstove that combined with my pile of green wood to give off about as much heat as a toaster oven. In the middle of the winter I’d almost burned the cabin down with a chimney fire, and soon after that had given away my cat Alice, who I loved deeply, because I decided she deserved better than to spend her golden years shivering or on fire beside a penniless idiot. I wrote something every day, one way or another, even if it was so cold in the cabin I had to wear my fire-damaged gloves. Most of the writing was an ongoing attempt at a novel that never found a heartbeat. As the useless pages piled up I began to sort of lose it. By “it” I mean hope, sanity, what have you. So just for something to do to keep from going crazy or to pass the time I started picking cards at random and writing about them in my journal by the dim light of a propane lantern. Over this past weekend I tried to find those descriptions, but wading through the dense thicket of failure in the journals from those years proved impossible. It took about two minutes of searching through one page after another of airless desperation before I shut down like a fried computer. But I know that one of the first cards I wrote about was this Ron Schueler card. I’m pretty sure I noted his big White Sox collar, and maybe I noted the partially hidden billboard behind him seeming to advertise Brut cologne. I do know I interpreted his gaze as a reflection of my own souring expectations, that existential dyspepsia that seems to say I thought things were going to turn out differently somehow. Now it's been long enough since then that I see that things, at least for me (I can't speak for Ron Schueler) turned out exactly as they should have. And not only that, they weren't half bad. There were stories. There were songs. There were even plenty of times when I really liked teaching. (I hope I can do it again someday.) I remember a lot of nervous sweat and stammering coming from me, and a lot of blank stares coming from my students, but I also remember some days when it actually felt like I had a job that wasn't just dumb labor for once in my life. I talked about Jack Kerouac and Denis Johnson and Blade Runner and D. Boon and Muhammad Ali and whatever else came to mind, every subject somehow relating, or intended to relate, to how much I loved writing, even how much I loved life, how much I wanted the students to get excited about something, anything, and try to put it into words. Sometimes I think some of it even came across. As for the rest of it, the cabin and the loss of Alice and the stillborn novel and the (eventual champion) fantasy team Desolation Angels, plus a lot of other things I guess I'll get around to mentioning some other time (such as the brief interval when I shared a house with a guy who was convinced the local health food restaurant was trying to poison him, or the brief doomed fling I had, or the deer I killed, or how spring felt at that cabin when the long cold winter finally ended): I guess I'll just say it was all a web of songs. I imagine Ron Schueler as the silent center of those songs. Even now, so many years later, new songs bloom from that Schuelerian silence. Yesterday I woke up with lyrics for the opening number of the Broadway musical Adjunct! in my head, the introduction to the main character song. Actually all I had is one line, the first line below, but I stumbled to my notebook (where else in this life is there to go?) and jotted down a bunch of possible accompanying lines: I'm just a margin on a page Ron Schueler (3)

2008-01-18 11:06

(continued from Ron Schueler (2)) I lasted two years as an adjunct, which matches the average stay by Ron Schueler on each of his four major league teams. He spent two years with the Braves, three with the Phillies, one with the Twins, and two with the White Sox. Maybe two years is the normal shelf-life for adjuncts. Most of the other adjuncts at my college also seemed to be just passing through. There were a couple of long-timers, but they had fit their adjunct duties into a sturdy arsenal of resourceful chisel-jawed remunerative pursuits, one guy teaching a couple of classes when he wasn’t leading tours through the Amazon rainforest and selling photographs to National Geographic, another guy maintaining his on-campus reputation as a ruthless grammarian in between professional jazz trumpeter engagements. Most of the others seemed to view the low-paying, no-insurance, no-security job as a steppingstone to something better. I may have entertained that thought, too, early on, but in the same blurry, hypothetical way that I daydreamed about someday publishing a novel or owning a house or ceremonially passing my baseball cards down to a son. It became apparent eventually that the job was merely another in my long line of crumbling ledges to cling to by my fingertips. One day while clinging I stopped in to see my old teacher and good friend Tony, who had helped get me the adjunct job. Tony told me of a dream he’d had the night before. In it, he’d gathered me and his wife together to tell us that he’d come up with an idea for a Broadway musical. One of the clearest impressions from the dream for him were the looks on our faces as he described the idea. First we were skeptical, then alarmed. “It was a whole musical about adjunct professors,” Tony explained. “I even remember the big closing number. Paaaart-timers are indispensable!” Tony came up out of his chair behind his desk to sing this last part. As he did I saw the whole thing in my mind, a stage full of singers and dancers wearing fake bald spots and glasses, wool sweaters and corduroy, stacks of marked-up student papers in their fists, everyone leaping to and fro to express the unconquerable nature of the human spirit, the hero in the center of the action an adjunct who overcame all the odds, who found the song deep down below all the meaningless noise, who let the song flow through him, who found while singing that he and his fellow adjuncts and every last creature on earth were worthy of song. Worthy of love. Indispensable. I laughed so hard I felt temporarily cured. “The end of the dream was you guys walking out on me,” Tony said. “You were shaking your head and saying ‘I don’t know, man. I don’t know.’” (to be continued) Ron Schueler (2)

2008-01-16 14:12

Act II (continued from Ron Schueler (1)) I spend much of my waking life wired to a computer, so when the thing went down with a virus a couple days ago it felt like more than just the malfunctioning of an inanimate tool. I felt damaged, invaded. As the popups kept mushrooming relentlessly across the screen I had the urge to bash the computer to shards with a baseball bat and head for the hills. Maybe in the hills I’d find peace or maybe instead I’d feel the need to hack at my skull with a screwdriver to dislodge what I believed to be a wireless transmitter embedded inside. I mean maybe it’s too late. Maybe I’m beyond repair. This possibly fatal graft of my brain to the computer began about the time where we last left off. As an adjunct professor I was given space in an office shared by several other adjunct professors. I was also given the use of a computer. A friend from graduate school, Rick, had begun working as an adjunct professor at the school that year, and he helped me set up a Yahoo account. He had one, which he used to play fantasy football. “It’s fun,” Rick said. He seemed unconvinced. Still, I drafted a fantasy basketball team within minutes of creating my online proxy. I named them Desolation Angels, after Jack Kerouac’s saddest novel. There were days, plenty of them, when the Desolation Angels provided the brightest moment of my day. I didn’t have much else going on. I had an apartment with two empty bedrooms, blindless windows that stared unblinkingly at Time, and terror that crested four times a week in the firing-squad minutes directly preceding each meeting of one of my two classes. Each flare-up of terror gave way to a kind of public seizure that gripped me for 90 minutes before casting me back to my solitude sweaty and stunned, my voice raw, as if I had spent the entire hazy interval sobbing. The students gone, I sat at the head of the empty class until my legs stopped trembling. I usually felt ashamed about one or another of the things that had tumbled from my mouth during the ill-planned lesson. “Stupid, stupid, stupid,” I said out loud. But the Desolation Angels got off to a decent start and kept climbing. As the days got shorter and colder, I leaned on them more and more. I started coming into the office on weekends to study the numbers of guys on the free agent wire. I made shrewd pickups. I climbed into third place. I climbed into second. "I can win this," I said out loud. (to be continued) Ron Schueler (1)

2008-01-14 14:03

Act I In 1998 I applied for a job as an adjunct professor at Johnson State College, a small state school in northern Vermont. I had been living in Brooklyn for awhile, getting by on sporadic temporary jobs. I had been, among other things, a liquor store clerk, a proofreader, a writer of cheaply made books sold to school libraries. I was thirty, same age as the man pictured here. I guess I hoped the teaching job would lead me to a more purposeful existence. I had gotten my undergraduate degree from Johnson a few years before and was still close with two of my writing teachers there, who put in the good word for me. I didn’t have any teaching experience, but their recommendation helped me get the job anyway. Or maybe they just needed someone, a body. I was given two classes, Basic Writing and College Writing. The pay was meager, but that had never held me back before. I didn't have a car or even a driver's license but a friend gave me a ride to Johnson a few days before classes were set to begin. I had few possessions. I got a second floor apartment within walking distance of campus. The apartment had two small bedrooms, which I left empty. I slept on a futon mattress on the floor of the space meant for a living room. My little gray cat Alice slept with me, burrowing under the blankets and pressing up against me. There were no blinds on the living room windows, so light from the street lamps came in. It was hard to sleep. The view from these windows was of a bank with a digital sign that gave the time and temperature. If I wanted to know what time it was I just had to look out the window. If I didn’t want to know what time it was I was in the wrong place. I bought a card table and two white plastic chairs from the hardware store next door. I had borrowed a small television from my stepfather, and I set it up on a couple cardboard boxes. It only got a couple channels. I had a boombox, too, but there wasn’t much in the way of radio in northern Vermont. I found I missed the sports talk that had helped fill my hours in Brooklyn. Mike and the Mad Dog. The Schmooze. The two unused bedrooms faced the part of Route 100 that was known for a few hundred yards as Main Street. There wasn’t much on Main Street besides the hardware store and, further away, a place to buy beer, grinders, and gasoline. Just below the window in one of my empty bedrooms was a slight raised mound of concrete in the sidewalk, right by the doorway of a vacant storefront. Maybe it had once been a doorstep. Teenagers with skateboards were drawn to the concrete mound. It seemed there were always two or three of them out there, taking turns failing some attempt at a trick involving the mound of concrete. The same sound, again and again: rolling wheels for a few seconds, then the clattering of the skateboard, then a pause, then the same sequence again. I sat in my apartment trying not to listen and trying not to stare at what time it was. I bought generic macaroni and cheese and Molson and chocolate at a grocery store just on the other side of the bank. I didn’t have a bottle opener, so I had to pry open the caps of the beer on the kitchen counter, but I wasn’t very good at it, so I ended up having to pound on the top of the beer until my hand was bruised and foam had spilled onto the floor. The formica edge of the counter got torn away from the particle board beneath. The days went by. "My name is Josh Wilker," I eventually said to a room full of 18-year-olds. "I’m going to be your teacher." The Best Everyday Player of the 1970s

2008-01-11 12:31

Though Bill James does not designate a best player of the decade, he does identify the winner of our poll, Joe Morgan, as the best player in four straight years, 1973 through 1976. Only Honus Wagner in the first decade of the twentieth century had a longer unbroken string of dominance (in James' estimation the Dutchman was tops in baseball for seven straight years). Of the players considered in our poll, Joe Morgan ranks the highest in James' all-time list of players, at 15. Two players at the tail end of their careers in the 1970s rank higher, Hank Aaron at 12 and Willie Mays at 3. Other players getting votes in our poll were ranked thusly, starting at the back: 82. Willie Stargell (James' choice for "Most Admirable Superstar"); 64. Rod Carew; 57. Reggie Jackson (James' choice for "Least Admirable Superstar"); 44. Johnny Bench; 33. Pete Rose. Ken Singleton was the only player receiving support in the poll who was not ranked in the top 100 by James, but he is ranked by James as the eighteenth best rightfielder of all time. Singleton and Stargell are the only two of our players who did not make it onto James' major league all-star team for the decade, passed over in the outfield in favor of Bobby Murcer, Reggie Jackson, and Bobby Bonds. Pete Rose is on that all-star team as a utility man, which would seem to make him the most vulnerable member of the squad if not for James' high estimation of him in the overall rankings. That ranking made me feel a little better about spending so much verbiage lobbying for more consideration for Rose as one of the very best players of the decade. I'm sure part of my inspiration in doing so was reading, on some earlier occasion, the rhetorical question Bill James uses to sum up his thoughts on Pete Rose's ranking in the pantheon of the game: "Which is better to start a pennant race with, a guy that you think might be the MVP, or a guy that you know is going to hustle every day and get 200 hits?" Geoff Zahn

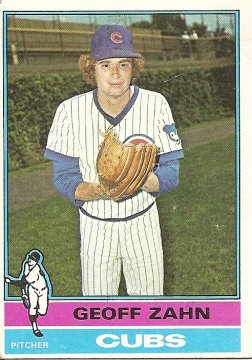

2008-01-11 06:18

No angels, no devils. Maybe some celestial functionaries, two of them, sitting together a little ways away, slightly elevated. But these figures, if they even exist at all, can only peruse the goings-on below, powerless to influence them in any way, the world of the beyond a bureaucratic morass, reports compiled and filed away unread. So there is only this, this life in the foreground, this wall close at our backs. This wall! Some find it quaint. But it's so close it tenses your shoulders, tightens your features, subtly riddles your cheer. It even sours the prayer hidden in your hands. You are on the brink of bursting out laughing. No joke has been told. Luis Gomez

2008-01-09 04:13

Is life a battle between good and evil or an inconsequential rest stop between oblivions? Consider Luis Gomez, the benchwarmer, waiting slack-armed for his turn in the batting cage, where he will likely have only enough time to momentarily practice bunting before a Blue Jay regular commands him to step aside. As he waits for this truncated, ignominious turn, two blurry figures hover above his narrow shoulders, each figure perfectly positioned to whisper influence into an ear. But what could these indistinct spirits possibly have to say to Luis Gomez? In his 8-year major league career the utility infielder batted .210 with a .261 on-base percentage and a .239 slugging percentage. He never hit a home run. He stole 6 bases but was thrown out trying to steal 22 times. Once he was called on to pitch in a bullpen-savaging blowout. He gave up three runs in one inning. In his final game he batted 8th in the order, just above the pitcher’s spot, for a lineup that was 1-hit by Mario Soto. The last of Gomez’s fruitless at bats was a popup that whimpered to extinction in the glove of the opposing shortstop. He stands here somewhere in the middle of that featureless career, waiting for a couple weak swings in the cage, and the two entities hovering near his ears seem incapable of making themselves understood. They will only mutter incomprehensibly as they fade, the two voices indistinguishable from one another, no guidance, no angel and devil, no choice between paths, no paths at all, or maybe infinite paths, all of them leading to dissolution. Pete Rose in . . . The Nagging Question

2008-01-07 10:09

There’s a lot of voting going on lately, what with the New Hampshire primary and the announcement of the results of the Hall of Fame vote both happening tomorrow. I was going to spend the morning writing about the existential implications of a particularly light-hitting utility infielder from the 1970s named Luis Gomez, but I feel like getting into the voting frenzy instead, especially since the most likely candidates for this year’s official seal of baseball immortality come from the ranks of the Cardboard Gods. Some of the more deserving candidates, including Alan Trammel, Dale Murphy, and Tim Raines, started to become prominent just as my childhood was ending, but the other names expected to make the strongest showing in this year’s vote were in or at least entering their prime during my baseball card years: Jim Rice, Goose Gossage, Andre Dawson, and Bert Blyleven. I have no inside knowledge about this, and haven’t researched the reports of those who do, but if I had to guess I’d predict that Rice and Gossage get in tomorrow, with Blyleven a narrow miss. Whatever the result, it is sure to stir up controversy about the arbitrary nature of Hall of Fame voting. If Rice gets in, many will wonder why he’s in and, say, Dick Allen isn’t. If Blyleven doesn’t get in, many will wonder why he’s not in and, say, Don Sutton is. Why Lou Brock but not Tim Raines? Why Pee Wee Reese but not Alan Trammel? Why 1930s basher Chuck Klein but not 1990s basher Mark McGwire? (OK, that last question was kind of loaded, or perhaps even juiced, but the point is every player is a product of their times, more or less, and so why ignore the inflated numbers of the 1930s—a segregated era, no less—while completely discounting the inflated numbers of the 1990s?) You know, I don’t know the answer to any those questions. So instead of trying to answer them, I propose to pass the time today in the pursuit of determining which of the Cardboard Gods is most deserving of an even more arbitrary and ridiculous designation: Best Everyday Player of the 1970s. I got the idea for this designation a few days ago, during a discussion about Reggie Jackson on Bronx Banter. A participant in the discussion, williamnyy23, provided a list, via baseball-reference.com, of the top twelve OPS+ averages in the decade among players with at least 5,000 plate appearances (for more on OPS+ see baseball-reference.com’s glossary; basically, it is the best single statistic for reflecting a player’s worth as a hitter): 1 Willie Stargell 156 OPS+, 5083 plate appearances So I present that list to you, the voters, as the ballot for Best Everyday Player of the 1970s. But first, a few things:

Who gets your vote? Marty Pattin

2008-01-04 06:29

Marty Pattin, on the other hand, was one of the guys whose "Born" town was the same as his "Home" town on the back of his card, in his case a place called Charleston, Illinois. I always noticed the same-Born-and-Home guys and considered them more solid than me, more rooted. I always imagined the houses they'd lived in their whole lives had white pillars in front and a tire swing hanging from an old oak in back. But by the time of this card Marty Pattin had been drifting around the American League for nine years, from Anaheim to Seattle to Milwaukee to Boston to Kansas City. If you trace these places on a map you will make something that looks a bit like the outermost curl of a spiral. Southwest, Northwest, upper Midwest, Northeast, lower Midwest. The only thing left to do to make the curl a complete spiral is to give it a center, and the center point, one would imagine, would be slightly north and slightly east of its most recent stop of Kansas City. In other words: Charleston, Illinois. I don’t know if Marty Pattin is actually on the brink of spiraling home in this photo. I could look it up of course, but sometimes I like to rely only on these cards and my memory. The card says he is 33 years old and that he has just gone 8 and 14 for the 1976 Royals. The memory says the 1976 Royals were really good, maybe too good to retain a 33-year-old 8 and 14 pitcher for too much longer. The memory is unclear on whether Marty Pattin endured throughout the Royals’ impressive run of division titles or conversely whether he vanished. He kind of morphs into Mark Littel a little in memory, a long reliever type far from the frontline status of Gura, Splitorff, and Leonard. The card also presents a photographic portrait of Marty Pattin, of course. He is enacting the familiar still-life-of-pitcher pose, which makes him look like a weary, aging mouthbreather bending down to reach for a doorknob. I wonder what's behind that door. |